Harvesting, for the farmer, is the busiest time of the year and for those involved with growing crops and raising livestock (mixed farming) it has to be undertaken in conjunction with all the other aspects of running the farm. Tony Mansell brings us this collection of memories and photographs which has been greatly enhanced by contributions by Geoff Osborne of Mithian.

Nowadays, mechanisation has made it less labour-intensive and some of the equipment now available is discussed in Geoff Osborne’s article Teagle Machinery: https://cornishstory.com/2020/10/03/teagle-machinery/ and in the book of the same name by Fred Teagle and Tony Mansell. 1

Once though, most of the work was undertaken manually, by the farmer and his workhands, albeit with the help of the faithful Shire and whatever form of early machines were available.

In this article we take a look at the process undertaken during that time – perhaps up to the mid-1900s – but it is impossible to date it accurately as the extent of mechanisation depended greatly on the size of the farm. Gradually though, even the smaller farms accepted labour-saving innovations and the traditional method of harvesting the crop using a scythe gave way to the reaper for cutting hay and sometimes corn and the binder for cutting corn. The binder was a massive step forwards because it not only cut the corn, but left is on the ground in neatly tied sheaves. These machines were initially pulled by giant work horses, but the horses were gradually replaced by tractors.

The processes, and certainly the terminology, varied across the country, and even from one end of Cornwall to the other. It should be appreciated, however, that most of the quotes and memories in this article relate to mid and west Cornwall.

Reaping and Binding

The scythe – an implement with a long curving blade used for mowing grass, corn grain, or other crops.

The scythe – an implement with a long curving blade used for mowing grass, corn grain, or other crops.

The photograph above shows Eric Dymond cutting corn with a reaper. This particular reaper is fitted with a sheafing gear, whereby a second seat is mounted off to one side on the machine and the person in that seat operates a device which gathered the corn and left it in sheaf-sized piles along the field.

The photograph above shows Eric Dymond cutting corn with a reaper. This particular reaper is fitted with a sheafing gear, whereby a second seat is mounted off to one side on the machine and the person in that seat operates a device which gathered the corn and left it in sheaf-sized piles along the field.

Elsie Thomas was born at Poltaire Farm, Silverwell, in 1915, and from a young age, could recall her father opening up a field by cutting the corn around the edge of the field with a scythe which he then bound into sheaves: the remainder, she said, was done by horse and reaper.

A common sight around Cornwall in the 1950s – the reaper-binder which both cut and bound the stalks into sheaves. Even after its introduction, the scythe was still a handy tool for cutting the hedge dram (the area of crop next to the hedge).

Jo Batten of Silverwell, raking the left-over hay from the field – nothing was wasted.

Jo Batten of Silverwell, raking the left-over hay from the field – nothing was wasted.

The Hay Harvest

The hay harvest involves cutting, drying and storing grass for use as animal feed. An age-old process which farmers have been carrying out for thousands of years.

A variation on this is the production of silage, essentially grass which has been stored without drying, and compressed until ready to be fed to the livestock. Silage, however, was not in widespread use during the period we are considering here.

In her memoirs, Elsie Thomas wrote, “Harvest was a busy time for farmers. The hay was cut with a reaper and, when fit, was turned using pikes. Everyone was involved – neighbours helped each other in those days. Most farms had what was known as a mowhay where ricks of hay and corn were built.”

She added, “If the weather was uncertain, hay was temporarily stored in pooks and later brought from the fields by horse and wagon”. The pook is a word relating specifically to hay and Geoff Osborne of Mithian describes it as a mound of loose hay, typically three or four feet high when it is made, probably settling down to around two feet when it has been there a day or two. He added, “The mound is circular, usually packed down a bit by banging it with a pike (pitchfork) as you pile it up. When you’ve finished, you comb the sides down so that at least some of the water runs off (a bit like thatch) when it rains. Pooks would be useful in a catchy season where the hay was too good to just leave on the ground to get wet, but not dry enough to be stacked in a rick for the winter. You have to remember that this was in the days of loose hay, manhandled onto a wagon and stacked loose in a hay rick – nobody had thought about balers at that time and horse drawn hay turners were in their infancy.”

Carrying hay – John Sandow on his smallholding at Always, Silverwell.

Carrying hay – John Sandow on his smallholding at Always, Silverwell.

The Hay Pole being used to build the rick at Crosscoombe.

The Hay Pole being used to build the rick at Crosscoombe.

Another view of the Hay Pole – in 1909.

Another view of the Hay Pole – in 1909.

Tony Paddy, my cousin, worked at Greenacres Farm, Silverwell, during his school holidays when he helped to bring in the harvest. His job was to work the grab mechanism on the hay-pole and he recalls that the last handful of the day was always playfully deposited over Alfred Hoskins’ head. Perhaps, an amusing twist on the Cornish corn harvest ceremony of Crying the Neck!

Cap’n Hoskins of Greenacres Farm loading his cart.

Cap’n Hoskins of Greenacres Farm loading his cart.

I well remember my role in building the rick with the hay-pole and Major – the Shire. I had to lead the horse two and fro to raise and lower the grab. I was warned that he had big hooves and was a bit ungainly when walking backwards but the inevitable happened and I had a sore foot for days.

Elsie Thomas recalled that during the harvest, tea or croust was taken out to the field with herby beer or some such drink.

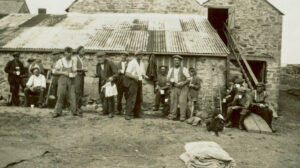

Croust time at Trevellas Manor.

Croust time at Trevellas Manor.

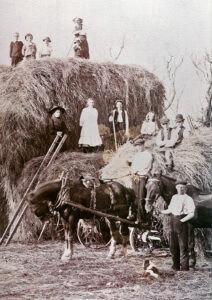

Building the rick at Sunbury, Trevellas – it often involved all the family.

Building the rick at Sunbury, Trevellas – it often involved all the family.

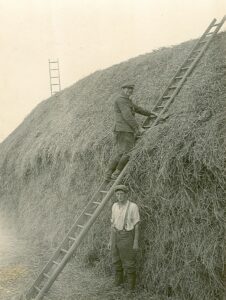

Harold Dark thatching the rick.

Harold Dark thatching the rick.

Thatched ricks in a mowhay at Wheal Rose.

Thatched ricks in a mowhay at Wheal Rose.

Jack Roberts of Wheal Davey Farm, near St Agnes, was fastidious in his rick building. The appearance of the thatch and the alignment of ropes seemed as important to him as the protection from the weather.

Hay Knife used for cutting hay from a rick as required for feeding the livestock.

Hay Knife used for cutting hay from a rick as required for feeding the livestock.

The Corn Harvest

Michael Tangye (Whythrer Meyn) of Redruth provides us with a story of a very traditional farming technique – the hand mow. He wrote about it in an article which first appeared in the Old Cornwall Society Journal in Autumn 1997 and was entitled The Mows in West Cornwall.

“In September 1990, when approaching Zennor churchtown, it was a surprise to see several corn mows, built in the traditional manner. On inquiry it was found that they had been constructed by Mr Arthur Mann of Trewey Farm. He subsequently informed me that he enjoyed using traditional farming methods, and still cut his corn with a binder drawn by a Shire mare. Unfortunately, he knew of no traditional terms relating to the craft of mow construction, only that they were either hand mows, those high enough to be built by standing, or knee mows, those built using a short ladder. He used 60 to 65 sheaves in each mow [rhymes with cow].”

Michael also wrote that G B Worgan, in 1811, noted the typical arish mows of West Cornwall, remarking, “They were admirable for protecting corn in bad weather, or a catching harvest, for up to six weeks. They were a sort of corn pyramid being formed with sheaves set upon their butts, and leading towards their centre. The workman gets upon them on his knees, an assistant putting sheaves in their proper places before him, while he crawls round the mow, treading them in this manner with his knees, applied about the binding place, and continuing thus to lay course after course, until the mow be deemed high enough; observing to contract the dimensions as it rises in height and to set the sheaves more and more upright, until they form a sharp point at the top which is capped with an inverted sheaf, either of corn or reed.”

Michael continued, “We find further information about harvesting and mows in the Penzance-based newspaper, the Cornish Telegraph, on the 22nd of August 1876, in a letter signed ‘W B’ – almost certainly William Bottrell. In his letter he named two types of arish mow, one called Pederack which was ‘conical in shape with the ear ends of all the sheaves turned inwards and upwards’. The other was called Brummel, or a Culver House mow, which ‘is in shape like an old-fashioned round, stone-built, pigeon-house, having the part which answers to a culver-house roof finished with the sheaves turned, ear-end downwards and outwards. A Brummel Mow is the best for continued moist weather because the ears on a mow top are less liable to sprout when reversed’. He added that ‘an ill-shaped bulging Pederack mow is said to be, in derision, like an old culver-house, by those who don’t know what the object of their comparison means’.” (Brummel = bar mol; Pederack = square)

Culver House, Bussow, Towednack. (Photo: M Tangye)

Culver House, Bussow, Towednack. (Photo: M Tangye)

The letter also included a list of West Cornwall dialect terms used in conjunction with various aspects of harvesting:

Dram: a swathe of cut corn or hay.

Collebrands: defective and smutty ears of corn supposed to be blighted by the fine weather lightning, which is called by the same name.

Colp: a short rope for carrying sheaves from the moway to the barn.

Keveran: a strip of hide, or leather, which unites the two sticks of a threshal, or flail. (Nance gives us Keveran = Cornish Kevran = a fastening or bond). The threshal was also called a hand-staff or slash-staff.

Liners: threshed wheaten sheaves.

Layer: a winnowing sheet.

Ishan: the dust which comes from winnowing. The refuse, consisting of defective grains, seeds, etc., was, by old winsters or winnowers, called attal. Later on, Ishan was the term used for the dust and empty corn ears separated out by threshing machines. This Ishan was blown into a big pile, which was used for livestock bedding.

Reeve: to separate small corn with a fine sieve.

Kayer: a coarse sieve.

Michael also referred to Bernard Victor, a Mousehole fisherman with a knowledge of the Cornish language which had survived in West Cornwall. He submitted an essay on the subject in an 1879 competition in which he included a list of dialect words, many of which stemmed from the language and some referring to harvesting:

Kay-yer: a course windowing machine.

Pilles: gleanings in the harvest field.

Tummels: a large quantity of straw or hay.

Piler: A farm implement used to pound, or cut, the beard off barley in winnowing (vide Cornishman 8th May 1879)

The building of mows in West Cornwall in the 1930s is also described by Alison Symons in Tremedda Days, her delightful account of farming in Zennor. “A shock was chosen for the centre of each mow, and all helpers carried sheaves to a circle round it and handed them to the builder. He built outwards until the diameter measured about eight feet, then upwards. The beard of each sheaf pointed towards the middle and slightly upwards. As the mow grew taller the builder had to climb up on to it and continue building, circling the mow on his knees. On reaching six feet in height, the mow was gradually brought to a point, which was firmly bound around with lengths of twisted straw.”

Geoff Osborne of Mithian has a clear memory of harvest time on the family farm at St Just-in-Penwith. “When you cut corn with a binder, the sheaves need to be protected from the worst of the weather and to have enough air circulating around and through them so that some drying occurs. Bear in mind that corn cut with a binder would be ripe but too green for threshing. The sheaves are initially put into shocks (I think up-country the call them stooks), which comprise two pairs of sheaves leaning against each other with another sheaf at each end, making six in all. They would typically be left there for 10 days or a couple of weeks to dry out. If the weather had been really good, they might be then taken into the yard and put into a rick to await threshing day.”

Geoff continued, “I’ve never heard of a Catching Harvest but a Catchy Harvest is when the weather is not very co-operative and you have to do a bit when you can. In this instance, the crop would need further drying, and four or five shocks would be put together into a hand mow – a good way to get the corn into a drier state before taking it back to the rick in the yard ready for threshing. For a hand mow, you make a cone of four sheaves, then another ring of sheaves around the outside, after which you work upwards in a spiral. It would be built entirely whilst standing on the ground and would have about four spirals of sheaves. A knee mow is exactly the same concept but a lot bigger diameter and height. To build it, you have to climb on top of it and kneel with your knees around either side of the conical top. I’ve only ever seen a knee mow built once.”

It may be thought of as an idiosyncrasy but Jack Roberts of Wheal Davey Farm, always built his mows with the knots of the binder-twine facing towards the centre of the mow so as to avoid them becoming gathering points for rainwater.

Assembling the sheaves into shocks.

Assembling the sheaves into shocks.

The Cornish festival of Crying the Neck (Guldize) was once a major occasion in the local calendar. The farmer cut the last patch of corn with a traditional scythe and shouted “I ‘ave ‘un! I ‘ave ‘un! I ‘ave ‘un!”. Those present responded, “What ‘ave ‘ee? What ‘ave ‘ee? What ‘ave ‘ee?”, with the reply being: “A neck! A neck! A neck!” After this, everyone joins in shouting: “Hurrah! Hurrah for the neck! Hurrah!” This ancient ceremony has been resurrected in many areas, mainly due to the efforts of the Old Cornwall Movement.

Harvest time was always exciting for the children.

Harvest time was always exciting for the children.

Hand mows with Mithian Church in the background. (Photo Ken Young)

Hand mows with Mithian Church in the background. (Photo Ken Young)

Making a knee mow at Tregaminion, Landewednack, circa 1864-6. (Photo: W Brooks, Penzance – Royal Institution of Cornwall)

Making a knee mow at Tregaminion, Landewednack, circa 1864-6. (Photo: W Brooks, Penzance – Royal Institution of Cornwall)

Taking the sheaves from shocks and loading them onto a wagon using pikes.

Taking the sheaves from shocks and loading them onto a wagon using pikes.

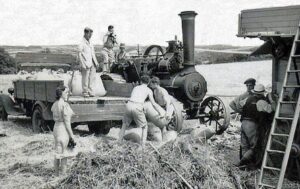

Elsie Thomas said, “Later on, the threshing machine arrived: it was pulled by a traction engine for which my father had to fetch coal and water. Three men came with the machine and they joined us in the house for breakfast and supper – they had to arrive early to get up steam. In the early 1900s the men who didn’t have a bike or pony and shay, stayed on the farm overnight. The corn was threshed, the grain stored in the barn and the straw put in bundles in a rick. The dowst was stored for use in winter. The ricks had to be thatched and roped down – it was generally my job to carry the rope with a long pole.”

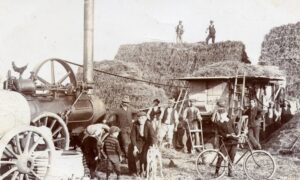

A busy day with the thrashin’ (sic) set and steam engine set up in the mowhay – next to the rick.

A busy day with the thrashin’ (sic) set and steam engine set up in the mowhay – next to the rick.

Neddie Mewton’s thrashin (sic) set in action. (Photo: Ken Young)

Neddie Mewton’s thrashin (sic) set in action. (Photo: Ken Young)

Elsie also referred to the essential aspect of refreshment for the harvesters and at Wheal Davey Farm it was no different where the workers were fed and watered with mid-morning croust of saffron or yeast buns and a mug or two of tea. A couple of hours later would see everyone sitting down for dinner (or lunch if you prefer) which would consist of tiddy and turnip pie, under-roast or pasty. This was invariably followed by rice pudding. A well-remembered story is of one of the helpers, Hartley Stevens, politely apologising for having to leave the table but he had to go outside to remove a mouse from his trouser leg.

Loading the freshly threshed bags of corn.

Loading the freshly threshed bags of corn.

A feature of all Cornish communities was the Harvest Festival, when chapels were decorated with the fruits of the harvest, thanks would be given, and the produce would be sold to the highest bidder. Young boys would usually act as runners – delivering the produce and collecting the money – and if the item was a bunch of grapes, then it was often the case that there were a few missing by the time it reached the purchaser.

There is a degree of nostalgia attached to the harvest of times past but for those involved, it was simply a necessity, a race against time involving a lot of hard work. Relief too, and the satisfaction that the ricks were built and that there was sufficient produce to feed and bed the livestock throughout the winter.

Postscript from Geoff Osborne December 2024;

Some time in the dim and distant past, I can recall something that you wrote which involved a horse drawn reaper with a sheafing gear attachment – this photo shows one in action. As the mower moved down the field, bunches of corn where left in discrete lots, which the women then bound and the men stood up in shocks. The facebook post was from Bryan Holmes and features an Irish location. (Geoff Osborne)

References:

- Teagle – Reflections on 75+ years 1937-2015 by Fred Teagle and Tony Mansell

My thanks to those who have contributed to this article and to the unknown photographers.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history and is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and a sub-editor with Cornish Story: an Institute of Cornish Studies initiative.

A lovely account of harvest, back in the day. I remember it well.

At threshing time they’d encircle the rick and machinery with wire netting. Two or three good rattin’ dogs were introduced and any rats or mice were soon despatched to the grand threshin’ ground in the sky.

I remember just one occasion seeing threshing done by steam at Polglaze Farm Leedstown, Nr. Hayle. There the traction engine cracked her boiler, was towed away and never used again!!

A great collection of photos.

I just about remember farming as in these photos – my Dad still used such implements such as the scythe to cut grass and a hook to shave off hedges when I was young.

The photo labelled ‘Taking the sheaves from shocks and loading them onto a wagon using pikes’, is almost certainly Pencoose Farm at the top of Kenwyn Hill Truro – before WW2. From 1940, Pencoose was farmed by Harry Warren who was previously (until late 1939) farming at Lambriggan Farm Penhallow.

Hi Susan,

I wondered if you know any more history about Pencoose Farm, Kenwyn, Truro??