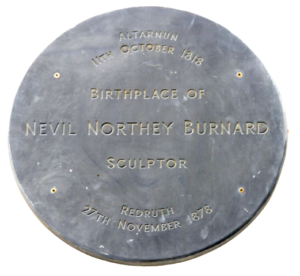

Neville Northey Burnard was a Cornish sculptor born in the village of Altarnun, on the edge of Bodmin Moor. Paul Phillips of Helston tells the story of this talented man and his work.

Nevil Northey Burnard was the son of a stone mason, George Burnard. He was born and lived at Penpont, (Penpont was the old name for Altarnun village, it was a small collection of houses, like a “churchtown”, but across the bridge from the church) in Mill Cottage with had mullioned windows and a newel staircase. He was born on 11th October 1818 and was baptised on 1st November that same year. The only education Burnard ever received was at the hand of his mother. She kept a Dame School and made straw bonnets, a common trade in some areas, in her spare time.

The Wesleyan chapel on the left, next to Burnard’s cottage.

The Wesleyan chapel on the left, next to Burnard’s cottage.

He was a mortar boy to his father and would often slip away and cut figures of men and animals on an old oak door and probably any other flat surface he could find, such was his enthusiasm for stone cutting. No doubt he received many a cuff around the ear for not keeping up with the work he should have been doing. His first tools were nails which he kept sharp by the use of a grinding stone, this was before he was able to acquire anything so lavish or as expensive as a chisel.

At that time there was no machinery for the facing of slate so he used an old French ‘burr’ which is a portion or segment of a French millstone. Such millstones were formed in four parts and then cemented together. This so called ‘burr’ he would mount in a rough wooden frame which he used in a similar manner to which a carpenter would use a plane, to and fro’ over the surface of the piece of slate which he was preparing for his father to fashion into a suitable headstone or other memorial, having secured it on a bench or ‘horse’ which is a kind of trestle arrangement. Existing examples of such pieces can be seen all over Cornwall and beyond and will be found to be most perfect in flatness and smoothness.

The Delabole slate which was employed for most of this monumental work surprisingly lent itself to being sculptured. Particularly in North Cornish churches there are numerous examples of monuments richly sculptured with heraldic figures of the 16th and 17th centuries, all as sharp today as the day they were subjected to the chisel’s point and left the workshop.

At the age of 14, Nevil cut a tombstone to his grandfather; that now stands in Altarnon Churchyard and is evidence of great skill, artistic sense and fineness of detail that would have done a far more experienced man proud. There are other stones of his there too. There are also one or two there by his brother George. There was an old man in the village of Altarnon who used to sharpen the nails on a grindstone for him and with which he did his carving on slate.

Young Nevil showed a talent for carving stone at an early age. Aged sixteen years, he sculpted a relief portrait of John Wesley over the doorway of Altarnun Wesleyan Chapel next to his home.

Burnard’s Sculpture of John Wesley

Burnard’s Sculpture of John Wesley

From Altarnon he went to Fowey where the late Sir Charles Lemon, of Carclew took him in hand. At the age of 16 he carved another relief in slate of a group including Laocoon the Trojan Priest in Greek mythology and his sons.

Laocoon the Trojan Priest

Laocoon the Trojan Priest

This work was granted a silver medal at the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society In 1834. This carving executed by a sixteen-year-old lad from a wild moorland village without any instruction and copied from a wood–cut in the Penny Magazine, and with tools of his own making, was considered to be remarkable. Nevil was sent to London, where again through Sir Charles Lemon’s influence, was presented to the Queen and Prince Consort and was allowed to cut a profile of the Prince of Wales, who was then a boy, of course. This portrait was sent to Osborne House where it met the approval of the parents. Sir Charles Lemon further introduced the young lad to Sir Francis Chantrey, one of the finest English sculptors of his day, and it was he who secured employment for him as a carver in one of the most celebrated ateliers in London. (An atelier, by the way is a school of fine art,) Young Burnard went on to replicate his profile of the Prince of Wales in marble for the Public Hall in Falmouth. The general opinion expressed was, ‘that it amply sustained the early expectation which had been formed of his talents’. So, being so well launched in his profession as a carver in London, he naturally found employment in the studios of the best sculptors of the time, namely, Bailey, Marshall, and Foley. There was no lack of work which brought with it a regular payday.

Caroline Fox, the daughter of Robert Fox was of the influential Falmouth Quaker family. In her ‘Memories of Friends’ Caroline wrote, and I quote: – “1847 October 4th – Burnard, our Cornish Sculptor, dined with us. He is a great powerful pugilistic-looking fellow at twenty-nine; a great deal of face, with all features massed in the centre; mouth open and all sort of simplicities flowing out of it. He liked talking about himself and his early experiences. His father, a stonemason, once allowed him to carve the letters on a little cousin’s tombstone which would be hidden in the grass; this was his first attempt, and instead of digging in the letters, he dug around them and made each letter stand out in relief.” Caroline goes on to say, “His (Burnard’s) stories of Chantrey were very odd; (that refers to Sir Francis Chantrey) on whose death Lady Chantrey came into the studio with a hammer and knocked off the noses of many of the completed busts, so that they might not be too common – a singular attention to her departed lord. Described his own distress when waiting for Sir Charles Lemon to take him to Court; he felt very warm and went into a shop for some ginger beer; the woman pointed the bottle at him and he was drenched. After wiping himself as best he could he went out in the sun!” She continues, “He went first to London without his parents knowing anything about it, because he wished to spare them the anxiety, and let them know nothing until he could announce that he was regularly employed by a Mr Weekes. He showed us his bust of the Prince of Wales – a beautiful thing, very intellectual, with a strong likeness to the Queen – which was exhibited at the Polytechnic where it will remain.” That is the end of the quote from Caroline Fox’s resume of Burnard’s visit to her home. (It is presumed that these busts of which she knocked off the noses were the plaster casts in the original clay, from which the finished marble or bronze images would result). On March 1st 1849 she goes on to say, “Found a kindly note from Thomas Carlyle. (He was a great British Historian, satirical writer, teacher and more.) She then says, “He has seen ‘my gigantic countryman’ Burnard, and conceives that there is real faculty in him; he gave him advice and says he is the sort of person whom he will gladly help if he can. Burnard forwarded to me, in great triumph, the following note he had received from Carlyle with reference to the projected bust of Charles Buller:” Caroline Fox continues her story as follows; “February 25th.1849 … ‘Nay, if the conditions never mend and you cannot get that bust to do at all, you may find yet as often turns out in this life, that it was better for you if you did not. Courage! Persist in your career with wise strength and silent resolution, with manful, patient, unconquerable endeavour; and if there lies a talent within you, as I think there does, the gods will merit you to develop it yet. Believe me, yours very sincerely, T Carlyle.”

On the return of Richard Lander from Africa, after having traced the Nile through a great part of its course, Burnard was commissioned in 1852 to execute a statue of the great explorer for the column erected at the top of Lemon Street, Truro, in his honour. I understand this has been a cause for concern due to erosion. His only other public work of his that is of any consequence was the statue of Ebenezer Elliott the Corn Law Rhymer as he was known, that was in1854. I think Elliott wrote satirical poetry in his quest to get the Corn Laws that were causing so much trouble amongst the lower classes particularly, repealed. This statue was to be placed at the Market Place, in Sheffield. He was also commissioned to execute portrait busts of many men of importance, amongst these are; General Gough, Professor John Couch Adams his fellow Cornishman, Professor Ed Forbes and one of Makepeace Thackeray, which Burnard gave as a present to the Cottonian Library in Plymouth, where it stands above the door.

1852 print of the Richard Lemon Lander monument in Truro

1852 print of the Richard Lemon Lander monument in Truro

He also crafted a bust of Charles Buller, son of Charles Buller Snr, and his wife Barbara, members of well-known Cornish families. Charles Jun. was actually born in Calcutta, educated at Harrow, then privately in Edinburgh by Thomas Carlyle, he then went on to Trinity College, Cambridge. He was admitted to Lincolns Inn gaining a BA in 1824. He became a barrister in 1831.

Amongst other notable persons that he sculptured, and these were mainly busts and not full statues, were Richard Trevithick, which is now in the Cornwall County Museum, Dr George Smith, his bust has pride of place in Camborne Wesley Chapel.

Burnard exhibited at The Royal Academy on a number of occasions, 1855, 1858, 1866, and 1867. He married in London, and this is where I found a little ambiguity in my research. One source stated that he lost his wife at an early age and turned to drink. Another source states that he lost a daughter, Lottie at the age of eleven and it was this that turned him to drink. A third source stated that his turning to drink and his abandonment of his prosperous career was because of both of these tragedies. However, I think as far as our story goes it matters not which it was, either would have been a huge tragedy and one that struck him down in a big way. It was at this time in his life that he was probably at his peak and was in constant demand for public commissions.

Burnard was tall and big, with an enormous head which no normal hat could fit, so it was that all his hats had to be bespoke.

As result of the afore mentioned tragedies, he eventually got so low, that he became nothing more than a tramp. On one occasion he was found dossing in a barn at St Cleer, believed to be at the hamlet of Crow’s Nest and next door to the Sun Inn, which is now proudly known as ‘The Crow;s Nest’ and also boasts ‘fabulous, homemade food and real ales.’ This is near St Cleer and the Trevethy Quoit. He paid periodic visits to friends at Altarnun where kindly people fed him until he decided to move on yet again. He would make sketches, draw portraits at farms in public-houses in exchange for a few pence or perhaps a meal. He seemed always ready to write an article for a newspaper or to make an election squib, for either side. In fact, he was as clever with a pen and pencil as he was with a chisel. It is said, he was a most entertaining companion and able to converse on any subject.

And so it was, that he spent his time with members of high, but mainly with low society, particularly towards the end, that he lived by his wits, mixing with the highest but preferably the lowest of society. His last visit to Altarnon was in 1877, just three years before his death. He remained there on that occasion for a week, with hardly any clothes on his back and was boarded with an old playmate, a Mr S Pearn. He slept in the common lodging house at Five-Lanes. After he had been fitted out with some fresh clothes he made his way to the west of the county.

During this last visit to Altarnon he drew some large pencil heads which show a firm but delicate hand but his main delight was to work in miniature. There is also evidence that his mind at this time was just as steady as his hand, for he composed a poem on the death of a Mr. F. Herring, of which I have a couple of verses here.

I stood by the spot where late you laid him,

The spot to each of us most hallowed ground;

After the angels in white had arrayed him,

And his smooth brows with flowers immortal crown’d.

Who in the wilderness would wish to wander,

Whose feet have trodden once the promised land?

Believe that all is well, nor pause to ponder

On things that mortals cannot understand.

He is most bless’d that is the firmest trusting,

Believing One that’s far wiser than he

Is, for his good, the balance still adjusting;

So – tell my parents not to mourn for me.

I now can see what might have been my story,

Had I remained through man’s allotted day;

(Sorrow for joy, dark age for youth and glory:)

And bless the love that hastened me away.

And wafted me across the mystic river,

Where all discords and elements agree,

Calmed by His word, that can from death deliver,

So tell my loved ones not to mourn for me.

I find that ever so moving and ponder what sort of mind could sit down, probably in a pub and on a scrap of paper or back of a fag packet (as the saying goes) and compose such a wonderful tribute to someone who had been his playmate and who knew so well.

Yet that sensitive mind was always equally ready to lampoon anyone, whether friend or foe; probably accommodating his thoughts to the humour of those whom he happened to be. Perhaps the following is an example. One day he was making a sketch of a farmer called Nicoll and resorted to the public house in Liskeard with his patron. Whilst there he scribbled on a piece of paper which he handed to Mr Nicholl. There were only three lines, but they went like this, bearing in mind that the client’s name was Nicholl.

Cash is scarce and fortune’s fickle;

I should like to draw some silver now,

As I’ve all day been drawing nickel.

There is at Penpont House, Altarnon, a small profile head that he carved of himself. It is apparently a cameo in Plaster of Paris. It is said that he sketched his face by looking in a mirror, and then cut an intaglio in slate from that sketch. We would call an intaglio a relief.

Nevil Northey Burnard died in the Redruth Union or Workhouse at Illogan from a heart and kidney complaint on 27th November 1878 he is buried in a pauper’s grave at Camborne. In 1954 the Camborne OCS erected a Headstone on his previously unmarked grave. In 1954 the Camborne Old Cornwall Society erected a Headstone on his previously unmarked grave. Such was the end of this very fine and outstandingly talented young Cornishman!

Here is what fellow Cornishman, Charles Causley wrote of him:

Here lived Burnard who with his finger’s bone

Broke syllables of light from the moorstone,

Spat on the genesis of dust and clay,

Rubbed with sure hands the blinded eyes of day,

And through the seasons of the talking sun

Walked, calm as God, the fields of Altarnun.

Paul Phillips was born on 26th November 1937, at 2 Elm Cottages, Leedstown, near Hayle and lived there for the first nine years of his life. He attended Leedstown County Primary School, Helston Grammar School and, at the age of 16, he decided to join the police force. He applied to become a Metropolitan Police Cadet. His application was successful, and he spent 17 years in the Met. On his return to Cornwall, the day that the Torrey Canyon hit the rocks off Land’s End, he took over a small hotel in Porthleven. To supplement his income, and putting his police driving training to good use, he set up a driving school where he taught approximately 1,000 pupils. During all this time Paul maintained a fond interest in Cornwall and all things Cornish but particularly our ever so rich dialect.

What a lovely story! Everybody came alive as I was reading! Burnard was obviously very talented and he was just a simple Cornish countryman. The same as my great grandmotherTabitha Phillips who was born in Chacewater and went to London with her sister in the 1890s probably to avoid dying like her brothers in the mines. Life was difficult in Cornwall then.

A compelling story – thank you.

Neville Northey Burnard was my great, great, great grandfather and I have been trying to find out more about him. This article was really informative and interesting. Thank you so much for writing it!