Tony Mansell brings us a story of a kindly man who worked out of his shop in Charles Street, Truro. Jimmo was a cordwainer, a shoemaker, one who makes new boots and shoes from leather. The trade can be contrasted with the cobbler who, according to a tradition in Britain, was restricted to repairing shoes.

Tony Mansell brings us a story of a kindly man who worked out of his shop in Charles Street, Truro. Jimmo was a cordwainer, a shoemaker, one who makes new boots and shoes from leather. The trade can be contrasted with the cobbler who, according to a tradition in Britain, was restricted to repairing shoes.

Jimmo hummed a waltz as he marked out the shape of the cut on a fresh piece of leather: in his mind he was still playing with the D’Oyly Carte.

He paused and looked around his workshop, he enjoyed his work but Sullivan’s music was etched in his memory – had he really given it up for this?

He still had his music but his involvement was just local now. In his younger days he’d played two instruments: the string bass in the orchestra, the bass fiddle as he called it, and the tuba with the Royal Italian Band. It had all started in Ponsanooth Brass Band, when he was a boy, back in the 1870s.

It was a warm day, the shop was unbearably hot, too hot to work but there was much to do. His work paid the bills and he had nine mouths to feed.

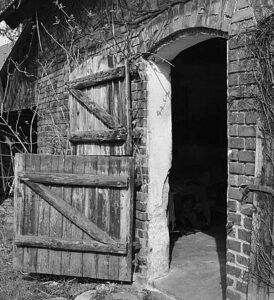

The stable door was open: it provided some ventilation and kept him in touch with the passing world. He was happy to see anyone, customer or not.

Pinafore danced across his mind and he began to beat time with his hammer: he paused, slightly embarrassed, as a young head peered in through the door.

“Whatcher Jimmo. How’re you doin’?”

“Hello Ginge, no school today?”

“Naa, finished for the summer.”

“I didn’t think the term ended ‘til Thursday.”

“Yea, well we weren’t doin’ much so I pushed off.”

“Now, how are we going to make a scholar of you if you keep doing that?”

“Aw, I’m fed up with school, don’t learn much there. As soon as I’m old enough I’m off down the mines.”

Almost before he’d finished the sentence, Ginger was inside the workshop with his back pressed against the wall. “Just saw Mother, she’ll give me hell for missing school.”

“Well you’d better keep your voice down then, otherwise we’ll both be in trouble.”

“Saw a copper just now, I had to duck into a doorway otherwise he’d have had me.”

“Quiet, she’s here. Morning Betty, how’s that young boy of yours. Still up to his mischief?”

“I tellee what Jimmo, he’s a right little ‘eller. The only time I don’t worry bout ‘n is when he’s at school. Another couple of days and he’ll be out and up to his tricks again.”

“Yeah, well I don’t suppose he’s any worse than the others. Here. I’ve got something for him. I’ve done up this pair of old boots. Get him to try them on and if they fit, he can have them.”

“That’s really good of you Jimmo, I wish I could afford to pay you something”.

“Not a word Betty, just don’t tell Mary. It’s not that she’s mean, she just doesn’t like me wasting my time.”

Betty Matthews smiled her thanks, placed them in her bag and headed off along Charles Street.

“Right Ginge, you nip down Lemon Street and you’ll miss her. A couple more days at school will do you good.”

“Don’t think so Jimmo. Me an’ me mates are goin’ fishin’ later. Thanks for the boots.”

With that he was gone, leaving Jimmo with his thoughts and a smile on his face. The boy would do all right in the world, he was sure of that.

He glanced at the shelf above his bench, the lost souls’ shelf as he called it. That was where he placed the boots and shoes that hadn’t been collected. Some had been there for years: the owners could be dead for all he knew. The green ones intrigued him most, the ones with the turned-up toes. Probably some theatrical type: if only he could remember who’d brought them in. “Only size four,” he thought. “Probably someone quite young”.

He turned back to his work and ran his thumb along the chalk line: his nail had become so hard that he could use it to cut the leather. Life was tough but at least he had the shop and there was still some money to be made from his music. His Riviera Orchestra was busy, in great demand for all sorts of functions. It wasn’t the D’Oyly Carte but he enjoyed it.

Working in the shop was lonely but every so often a head would pop through the doorway for a chat. Winter was the worst, the door was closed then. Mary rarely called and he wasn’t sorry about that. He loved her but she controlled his life and would run his business as well if she had the chance.

He poured himself a glass of cider from a pitcher, it was time for a bite to eat and he plonked himself down in his chair. This was his thinking time, when he pondered at the miracle of life and had his doubts about the hereafter. He’d never spoken to anyone about it but would love to know if others had similar thoughts. He’d been brought up chapel and taught to dispel such ideas. He’d learnt about damnation from the hell-fire preachers, their ranting had been scary but had always been a restraining factor in his life. He envied his friend Arthur Rogers. He was strong in faith and never wavered, even when his wife had drowned off Sunny Corner. But it was a lovely day, too good for such thoughts: he tried to put his mind to other things.

He looked up at the boots, the green boots. If only he could remember who had brought them in. Mary would have written it all down but he wasn’t good at paperwork and trusted his memory in all things. He had a good memory, honed on making music.

The boots reminded him of those worn by medieval jesters, that would tie in with the theatrical idea. If the owner had been local, he surely would have remembered him, he knew all the stage folk. He guessed that they’d been on his shelf for three or four years and his imagination took him on a journey that involved a young lad, destined for stardom. Perhaps he’d died before he could collect them, perhaps before the first performance. Where’s the justice in that Mr Preacher man?

Of course, they may belong to one of the little people…a spriggan or a bucca, maybe even a goblin. Please not a goblin, he’d had enough curses during his life without them joining in. He sipped his cider and smiled at his juvenile thoughts.

Perhaps they belonged to a girl, that could be why they were so small. He imagined some pretty little thing pulling them up over a slender ankle. If Mary could read his thoughts, he wouldn’t half get a tongue-lashing. But no, they belonged to a boy, he was sure of that. Like all the others on the shelf, they would stay there until claimed. Or until he was certain they were not wanted.

He threw the last of the cider into the slop bucket, he’d had enough. He’d love to sit there all day but he was disciplined. He had work to do, money to earn.

It was a couple of days later when Betty Matthews came into his shop again, she was carrying Ginger’s boots.

“What’s up love, don’t they fit?”

“We never got a chance to try them Jimmo … he didn’t go to school that day. Seems like he went fishin’ down Malpas and fell in. They haven’t found him yet.” She paused to recover her composure. “You know what a ‘eller he was but he was my boy and I loved him.”

“Of course you did Betty. I’m dreadful sorry, I was fond of him myself. Perhaps there’s still a chance.”

Betty shook her head, her mother’s instinct told her that he was gone. She passed the boots to Jimmo and shuffled out of the shop. As she disappeared from sight Jimmo rubbed his eyes. His head was full, thoughts of the hereafter, of Arthur Rogers and, of course, Ginge. He reached up and placed the boots on the shelf, the lost souls’ shelf, next to the green pair with the turned-up toes.

Epilogue:

A story of fiction? Well, yes, to some extent but Jimmo and Mary were real – they were my great grandparents.

Jimmo really did have a thumb nail tough enough to cut leather and he did make and repair footwear in his Charles Street workshop with no charge for the less fortunate.

He really was a musician with the D’Oyly Carte and, by all accounts, he was a lovely man.

I never met him – he died before I was born – but I’m sure I would have liked him. My biography of him can be found here: https://cornishnationalmusicarchive.co.uk/content/edwin-james-paddy/

Ginge: well, he’s from my imagination but there were many such boys and girls who benefitted from Jimmo’s generosity.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history, is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive specialising in brass bands, and a sub-editor with Cornish Story.

Lovely enthralling story. To be a cordwainer was a very good skilled profession in those days. My Great *2 Grandfather born 1821 was a cordwainer in Truro, eventually becoming an instructor of apprentices until 1874. Then he went a bit awry and went to sea and died of yellow fever in Calcutta in 1879.