Banking in Cornwall – Part 2: The early Miners’ Bank, 1771-1828

Categories Articles, Commerce & Industry0 Comments

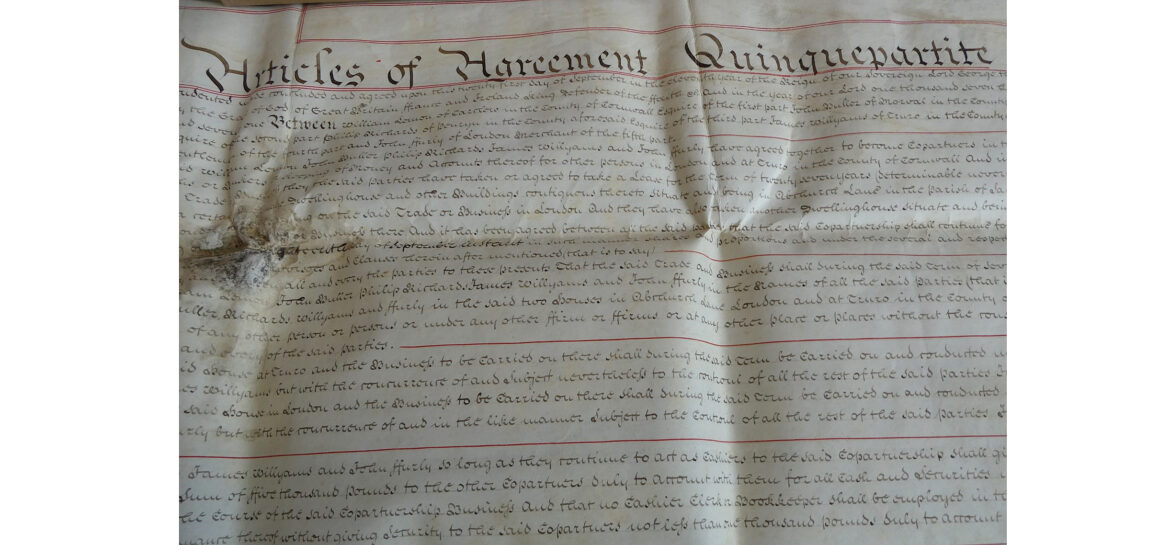

John Dirring has discussed the beginnings of banking in eighteenth-century Cornwall in the first part of this series. He now continues the story by relating the early history of the Miners’ Bank, established as a partnership under the `Agreement Quinquepartite’, the heading of which is shown here (Kresen Kernow, ref BU/431).

The oldest banks established as such in Cornwall (rather than growing out of other businesses or professions) were the Miners’ Bank and the Cornish Bank, both founded in 1771. Both were set up primarily to serve the interests and needs of their partners, and the business activities by which their fortunes had been made and continued to be maintained. The Miners’ Bank apparently had an antecedent in an earlier institution begun in Truro in 1759, which dealt in notes and post bills for £10 and £15. This is stated by Matthews and Tuke, in their 1926 history of Barclays Bank and its constituents (of which the Miners’ Bank ultimately became a part). No corroborative evidence has been found for this; nor is it known whether other banking services were offered. The Bank of England had issued post bills since 1728, which provided a more secure means of remittance than ordinary banknotes – in that an endorsement by the named recipient was required before payment could be made.

The official foundation date (and duly celebrated by a formal dinner in 1871, its centenary year) was 20th January 1771, when the `Copper Miners’ Bank’ opened in Princes Street in Truro. George Boase, in the banking section in his Collectanea Corbiensia, lists names for the original partners which have been faithfully copied by later historians such as Leslie Pressnell. These stand in need of some qualification. According to Boase, they were Francis Basset, John Rogers, Humphry Mackworth Praed, William Lemon, James Willyams, John Lubbock and `Mr Furley’ – which, as Pressnell points out, is one more than the legal maximum of six names allowed at the time in banking partnerships. Basset, Rogers and Praed soon seceded, with Praed joining instead in the formation of the Cornish Bank later that year; and Lubbock left to pursue his London interests.

However, it is highly unlikely that Francis Basset of Tehidy (1757-1835) was actively involved in banking at this date, as he was only fourteen years old in 1771; and about to change schools, from Harrow to Eton. He did join the Cornish Bank; but at a much later date. His father, also Francis Basset, had died in 1769; but may have been involved in the earlier 1759 institution, if it existed. There is also no evidence for any participation by John Rogers (who became Basset’s brother-in-law in 1776).

A fresh start was made on 21st September 1771, when the `Articles of Agreement Quinquepartite’ were drawn up between William Lemon of Carclew (near Penryn), John Buller of Morval (near Looe), Philip Richards of Penryn, James Willyams of Truro and John Furly of London. This document is held by Kresen Kernow in Redruth (Buller papers, BU/431). It describes a banking business to be set up for an initial term of seven years, in both Truro and London, with a capital of £2,500. At first, it was known as the `Copper Miners’ Bank’, as copper was the prime quest and main output of deep Cornish mining at that time, and required the greatest investment.

Lemon, Willyams and Richards were active and successful `adventurers’ or investors in Cornish mines, and the bank was formed primarily to serve their financial needs and those with similar interests and commitments. Adventurers generally thought of themselves as `miners’, although most probably never touched a shovel or went underground. The mines themselves were typically financed through the cost book system, and did not normally borrow money or have large cash reserves. Instead, the adventurers put up the capital and bore the financial responsibility; and the operating surpluses – or deficits calling for more funding – were shared among them at regular intervals, usually every three or four months. The rewards could be very large – and so could the losses in what was a high-risk and unpredictable form of enterprise with heavy expenses. The adventurers could thus have large amounts to invest as advantageously as possible, or be in urgent need of large loans to pay their calls. A bank serving their needs would therefore require opportunities for suitable investments, and immediate sources of loanable funds. Both were available in the manifold opportunities in the City of London, and the Miners’ Bank began with offices both in Truro and in the City. In the public gaze, it would have been visibly backed by the landed wealth and political reputations of Lemon and Buller; although all the partners were men of substance.

Each partner contributed £500 of the £2,500 capital, thereby having equal status in the bank, and they were to share the annual distribution of profits equally. Willyams was to be the managing partner in Truro, and Furly in London – where premises were leased at 14 Abchurch Lane, off Lombard Street. Both had to provide sureties of £5,000 against the possibility of fraud, errors of judgment or accounting mistakes. This was common business practice in those days and for long afterwards. Likewise, the clerks and bookkeepers to be employed by them each had to find £1,000; but there was no summary dismissal except for gross misconduct. The responsibilities assumed by the managing partners were rewarded by salaries, additional to their shares in the profits: £100 a year for Willyams, but £150 for Furly, reflecting maybe a larger responsibility in charge of the City business.

In the manner of the times, the partners had wide discretion in their individual conduct of the business; but some safeguards were in place. In accounting terms, the businesses in London and Truro were to be kept entirely separate, with the managers each accountable to the other partners. In commercial terms, written consent was required from all the partners for all loans and mortgages advanced over £10,000. The issue of the bank’s own notes could only be authorized by Furly or Willyams. To give the business a firmer footing, irrevocable written notice was required of partners wishing to leave before the seven years’ term of the agreement was up, and inheritance of shares in the event of death was confined to immediate family members. Early dissolution of the partnership had to be by unanimous sealed consent, and there were also provisions in the event of a partner’s insolvency. Partnerships in every kind of business in these times were normally made for fixed terms and subject to renewal; and partners came and went as their fortunes ebbed and flowed and new opportunities appeared. Finally, there was a procedure for the resolution of disputes between the partners, with outside arbitration.

The relationships between some of the partners were somewhat stronger than any legal agreement could make them; for there were family connections between Lemon and Buller, and between Lemon and Willyams. William Lemon’s mother was Anne Willyams (aunt to James Willyams); and William himself married Jane Buller, John Buller’s sister. John Buller himself married Ann Lemon, William’s sister; and there were further intermarriages in subsequent generations. Lemon and Buller were also in politics together, both being Members of Parliament. Sir William Lemon (1748-1824), as he became in May 1774, represented Cornwall as one of its two `county’ MPs continuously for the next fifty years; he had previously represented the borough of Penryn. Polwhele characterized him in later life as `the old country gentleman, faithful to his King without servility, attached to the people without democracy’. According to Brian Elvins, the influential `Lemon connection’ endured well into the next century, and transcended the emergent party politics in Cornwall. The wealth of the Lemon family came from mining – and continued to do so, with the later proceeds invested in land and property. It had been built up by the `great Mr Lemon’, Sir William’s grandfather, who had emerged from humble origins in the earlier eighteenth century.

John Buller (1745-1793), from an established landed family in east Cornwall, had little involvement in mining investment, being first and foremost a politician. In Parliament, he had represented Exeter, Launceston and West Looe successively between 1768 and 1784, and spent a lot of his time in London. With a Cornish income and metropolitan expenditure, the attraction for him would have been the financial links that the bank was setting up between Cornwall and the capital; surviving bank books of his in Kresen Kernow (BU/595) show the nature of his transactions.

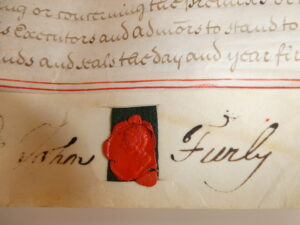

John Furly signed the Agreement in Lincoln’s Inn, London, where it was witnessed (from Kresen Kernow, BU/431)

John Furly signed the Agreement in Lincoln’s Inn, London, where it was witnessed (from Kresen Kernow, BU/431)

John Furly, a London merchant, seems to have dealt extensively in metals; and was involved in the seaborne tin trade between Cornwall and London. This much is indicated in the scant historical traces of him, by correspondence in the Forbes papers (A727.134) in the Falkirk Community Trust Archives in Scotland. He also seems to have been rather older than the other partners in the bank, bringing an extensive business experience to what was otherwise a young men’s enterprise. His son was in trade with him; and he is possibly the John Furly in the list of London merchants subscribing to a loyal address to the King during the Jacobite rising of 1745.

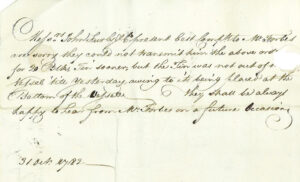

This formal note apologises to Furly’s customer Mr Forbes for the delay in unloading twenty blocks of tin lately arrived in London, as it was at the bottom of the hold. Earlier correspondence had advised the sailing of this cargo from Penzance (Falkirk Community Trust, A 727.134-30)

This formal note apologises to Furly’s customer Mr Forbes for the delay in unloading twenty blocks of tin lately arrived in London, as it was at the bottom of the hold. Earlier correspondence had advised the sailing of this cargo from Penzance (Falkirk Community Trust, A 727.134-30)

James Willyams (1741-1828) was from an old-established landed family whose seat was at Carnanton, near St Columb (nowadays the runway of Newquay Cornwall Airport is immediately adjacent), and also had successful mining investments. His administrative skills and residency in Truro fitted him for the managerial role in Cornwall, and for a time he also held a commission as a major in the Cornwall Militia. But above all, he gave continuity to the Miners’ Bank through all its varying fortunes; while other partners came and went he remained as managing partner, right up to his death in 1828.

Philip Richards (d. 1798) also had political connections; but he was primarily a merchant and mine adventurer. He was to become involved in the Cornish Metal Company, a short-lived venture which aimed to buy up the entire output of Cornish copper ore for seven years, and thereby maintain prices in a highly competitive market. But it was a hard age, and not everyone joined in. The Company lost money; but had succeeded in paying off its debts when it was wound up at the end of the seven-year term.

The division of the bank’s business in the manner specified in the Agreement between London and Cornwall, widely separated by distance and travelling time, was not a practicable proposition. After only five months, the London branch became a separate partnership. John Lubbock (1744-1816), now well-established in London trade, rejoined the business; and Lemon, Buller, Furly, Lubbock & Co was established at a new address at 11 Mansion House Street in the City. This soon became a London rather than a Cornish institution, although continuing to act as the agent for the Miners’ Bank – a much better business arrangement. Buller retired in 1776, Lemon in 1785; and Furly’s name also disappeared around this time. Lubbock found new partners, and the bank eventually merged with Robarts, Curtis & Co in 1860. In 1914 it was taken over by Coutts.

Buller, Lemon and Furly had also departed from the Miners’ Bank in Truro, as had Richards; leaving Willyams to find new partners in Cornwall. In 1793 the bank partnership became Rodd, Willyams & Gould. Of these Francis Rodd (1732-1812), of Trebartha on the eastern fringe of Bodmin Moor, had some mining investments; but like Buller his large estate was the main source of his wealth, and with the largest stake in the bank he became the senior partner. Dr John Gould of Truro (1740-1823) was nominally a medical practitioner; but would have spent much of his time managing his very extensive business interests in Cornwall and South Wales. Thomas John (d. 1822) was their senior clerk. Although public confidence in the bank sometimes wavered, it was a profitable concern. A surviving document from this period is a `minute book’ (Kresen Kernow, Willyams papers, W78), in which however the only business transacted is the annual division of profits between the three partners. It also records a division of some of the assets in 1806, when the partners were beginning to go their separate ways, and the relationship was becoming acrimonious.

Most of the work seems to have fallen on Willyams’ shoulders, and to help out he took John Williams (from the well-known mining family of Scorrier) into partnership. Willyams, Williams & Co revived the original `Copper Miners’ Bank’ name, and was effectively a new business. Rodd was no longer interested; but Gould felt excluded. John Gould Junior tried to intervene on his father’s behalf by complaining to Henry Hearle Tremayne, who had on occasion acted as arbitrator in past disputes. A stormy correspondence ensued; but it was to no avail. However, Williams resigned on 1st January 1810 to join the Cornish Bank; and as `Old John’ became a patriarchal figure in later years, dominating his family enterprises.

Once again James Willyams had to seek new partners; and in 1810 the firm became Daniell, Willyams, Vivian & Co. With this new partnership, the commercial orientation of the bank changed. The dependence on the fortunes of mining and its adventurers, at the mercy of world metal prices, was risky; the fortunes of the copper smelters across the water in Swansea (Abertawe) were much more dependable: to them, low ore prices were an advantage. In the town that was becoming regarded as `Copperopolis’, the smelting works drew on worldwide ore supplies as well as those from Cornwall. One of James Willyams’ new partners was John Vivian (1750-1826), who after an earlier career in Cornish mining was successfully developing the family’s Hafod smelting facility, of which his son John Henry Vivian (1785-1855) was the manager. According to Boase, the senior partner was Ralph Allen Daniell of Trelissick (1762-1823). However, his fortunes were now declining, and he would be unlikely to want to bear the unlimited liability of participation in banking. According to the documentary evidence cited in R.R. Toomey’s 1985 study, the new partner was Thomas Daniell, who like Willyams himself had his own separate interests in smelting; both were involved in the works at Llanelli. Thomas Daniell had been a language student alongside John Henry Vivian in Germany in 1801, so like him he was of the rising generation. Boase also lists a Joseph Knight of Bodrean (near Truro) in this partnership; but there is otherwise no mention of him. Joseph Hodge (retired 1850, died circa 1852), was now the `confidential clerk’, alongside Thomas John; who had become a partner by 1817. Hodge became a partner in 1826, which confirmed a rising social status; he eventually served as mayor of Truro.

John Vivian died in 1826; and a new partnership was formed, consisting of his sons Sir Richard Hussey Vivian (1775-1842) and John Henry Vivian, with James Willyams, his son Humphry Willyams (1791-1872), and Joseph Hodge. Sir Richard had achieved military renown as a hero of Waterloo, and had become a baronet and Member of Parliament; while his brother was entirely involved in the Hafod operation, and was resident in South Wales. This partnership had a very short life, as the Vivians elected not to continue their financial involvement in the risky business of banking, and James Willyams died in 1828.

The Welsh connection was very successful for the Miners’ Bank over a number of years, and had also been beneficial to the Vivians. It provided overdraft facilities for the purchase of ore in Cornwall, which could easily be paid direct to the mines. This could amount to £200,000 a year. For a short time in 1809, the notes of the Miners’ Bank had been circulating in South Wales, as they had been used experimentally by the Vivians for paying the wages at Hafod. Other works in South Wales, like Williams & Grenfell in Swansea in 1813, had tried issuing their own notes. In 1811, the Vivians had taken a controlling interest in the Mona mine and its associated works in Anglesey (Ynys Môn); an enterprise which at its peak towards the end of the eighteenth century had provided severe competition to the Cornish mines, but was now in decline. The Vivians brought in some Cornish workers, and also started paying them in Miners’ Bank notes. The bank, however, was unwilling to open branches in Wales to make the notes payable locally and hence more acceptable; and the practice soon ceased there as it had at Hafod. The Hafod account was moved later to the Bank of England (after it had opened a branch in Swansea in 1826), which the Vivians found to be more convenient and dependable for their expanding trade in London, Manchester and Liverpool.

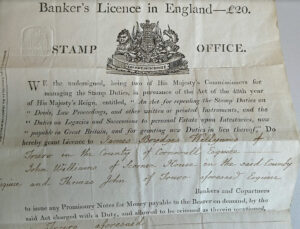

Humphry Willyams now succeeded his father James Willyams; in partnership with Joseph Hodge. His elder brother James Brydges Willyams had died in 1819, and it seems had never been a partner in the bank; although the first annual banker’s licence for the Miners’ Bank was issued with his name on it (perhaps misunderstood as his father’s) on 11th October 1808. These licences were primarily intended to authorize their holders as issuers of notes, and were an early attempt at regulating the banking sector. The economy was awash with private bank notes, some barely negotiable, in these years when the Bank of England was not making payments in gold; and they had become a major public and political concern.

The licence issued to the Miners’ Bank by the Stamp Office in London in October 1808 (from Kresen Kernow, W79)

The licence issued to the Miners’ Bank by the Stamp Office in London in October 1808 (from Kresen Kernow, W79)

The further story of the Miners’ Bank, up to its incorporation in the Consolidated Bank of Cornwall in 1890, will be told in a later instalment of this series. The next part will look at the early years of the Cornish Bank.

The first part of this series can be found using this link: https://cornishstory.com/2021/07/12/banking-in-cornwall/

References:

As with the other parts in this series, much of the information given here has appeared in the author’s doctoral thesis: J.W. Dirring, `The organization and practice of banking in Cornwall, 1770-1922: motivations and objectives of Cornish bankers’, University of Exeter (2015). This is available online via ORE Exeter.

Other works cited:

G.C. Boase, Collectanea Cornubiensia (1890)

P.W. Matthews and A.W. Tuke, History of Barclays Bank Limited (1926)

L.S. Pressnell, Country Banking in the Industrial Revolution (1956)

- Rowe, Cornwall in the Age of the Industrial Revolution (second edition, 1993)

R.R. Toomey, Vivian & Sons, 1809-1924: a Study of the Firm in the Copper and Related Industries (1985; publication of a 1979 University of Wales thesis)

- Elvins, `The Lemon family interest in Cornish politics’, in P.J. Payton (ed.), Cornish Studies: Seven (1999), 49-73

Grace’s Guide (online) for details of the Mona mine in Ynys Môn

Acknowledgements:

Thanks are due to the staff at Kresen Kernow, Redruth, and the Falkirk Community Trust for their help.

The photos of the documents in Kresen Kernow are by the author.

John Dirring comes from a farming background, and worked in the building and construction industry after graduating in economics from Lanchester Polytechnic (now Coventry University) in 1974. He returned to academic life in 1996 via adult education courses in astronomy and geology, before embarking on a Historical Studies BA at Exeter. From there, he went on to complete an MA and PhD at the Institute of Cornish Studies.

He continues with his study and researches in banking history; and is also very interested in the social aspects of money and credit, and the opportunities and challenges facing the new kinds of financial institution that are now becoming established in Cornwall and around the world.