The word evacuee slips easily off the tongue, perhaps too easily to convey the extent of the pain and suffering endured by those affected. For the parents who had to say goodbye to their children and for the youngsters themselves, some as young as five, who had to gather on a London railway station, label pinned to coat, gasmask around neck and suitcase in hand, waiting for a train to take them to an unknown destination, to live with strangers. Here, Tony Mansell fulfils one man’s dream of having his story put into print.

The parting was emotional, tearful. For some it was a rejection and many never forgave their parents for sending them away while for others, perhaps the majority, it was an adventure and their evacuation had a very positive effect on their lives. Frank Long was definitely in the second group.

“For some weeks prior to the outbreak of the Second World War there was a lot of activity at Perivale School.” So began Frank Long’s memories of wartime life in Ealing.

He recalled that there was a lot of talk about the likelihood of war. “We were too young to understand what it was all about but then, on Sunday 3rd September 1939, we gathered around the wireless to listen to the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, make an announcement. In a very sombre voice he told us that Germany had invaded Poland and because of this, we were now at war. People were visibly upset and some began crying.” Within a very short while, children were being shown how to use their gas masks and encouraged to help others with theirs. “We thought the masks peculiar and by blowing hard into them we could make squeaking and whistling noises; we had no real idea why we had to wear them. The older children were taught basic first aid; mainly how to bandage cuts and bruises.”

The sirens were tested for a few days and were dubbed “Moaning Minnie”, its screech was a signal to get to an air raid shelter as quickly as possible. At school, the children had to file out into the playground in class order where newly-erected blast walls protected them as they made their way to the shelters. They remained there until the “all-clear” siren sounded. On returning to school, the teachers blew their whistles and the children lined up in the playground to hear the register called. They then filed back to their classrooms.

At home, too, there were precautions and air raid wardens and first aid nurses called to make sure that basic safety measures had been taken like putting sticky tape on the windows to prevent the glass from shattering. Most families were provided with a steel Anderson shelter which arrived in pieces with assembly instructions. It had to be placed in a hole in the ground and covered with soil; many grew flowers and plants on top of it. This underground steel room was where people slept during the night time air raids.

Within days, men began to appear in army uniforms; they left to catch trains to the barracks to prepare to fight. On one occasion the air raid sirens started wailing and everyone ran home to their shelters or under the stairs where they were told it would be safer. Frank said, “My mother and I jumped over our garden wall but she tripped and injured her leg and the St Johns Ambulance Brigade took her to hospital. She was in plaster for many months and we were told that she was the first person to be injured in the war. The funny thing was that the alarm was only a practice.”

Very soon, reality struck home as the siren was accompanied by news of enemy aircraft heading for London, it was a bombing raid. It was dark and as families huddled in their shelters they could hear the sound of gunfire – anti-aircraft guns firing at the German planes. The sound of the guns, the airplanes’ engines and the explosions was frightening and the ground shook as the bombs hit their targets. Frank recalled, “I looked out and could see lights flashing and fires burning. The sky was lit with long beams of light, searchlights trying to pick out enemy planes. Eventually, after what seemed like an eternity, the sirens sounded the ‘all-clear’. It was still quite dark and we could smell smoke and see that London was in flames from the bombs dropped on the docks and the boats on the Thames. Incendiary bombs had started fires in some of the houses in our street and men were throwing sand on them to minimise the damage.” The raids continued night after night and it seemed that London was permanently on fire. Frank recalled a mixture of fear and fun as they searched for souvenir pieces of shrapnel.

London was not a safe place to be and the Government initiated its plan, “Operation Pied Piper”, which would see the evacuation of children and some adults from the towns and cities considered to be at greatest risk. Parents were encouraged to send their children to country areas, away from their urban homes where there was the constant risk of injury or death.

Frank was ten years old. He had two brothers, John who was eight and five-year old Laurence. It was agreed that just the two older boys would be evacuated. They were to travel with about a hundred other children from Perivale School to an unknown destination well away from London. Where they would be sent was not revealed until the morning of their departure. Frank recalled, “We said goodbye at the school, scrambled onto a coach to Perivale Station where we boarded an old steam train which we called the ‘Push and Pull it’, so named because it ran on a single track and either pushed or pulled its carriages. Arriving at Paddington Station carrying our gas masks, a bag of sandwiches and rock cakes and our meagre belongings, we headed for a large train which was already hissing steam and smoke. We were herded into numbered carriages with our teachers who were busy wiping tears from the eyes of the children, some of whom were fighting to get off the train to go home.” Frank recalled the faces of the teachers who were equally upset. The children’s cases, or bags tied with string, were thrown into the goods vans. These contained their clothes and perhaps a few toys as they had no idea when they would be returning. Because of the chance of an air raid, everything had to be done quickly. Suddenly, in clouds of smoke and steam, the “Cornish Riviera” was off with its precious load, heading for places of refuge in the far west.

It was dusk and the hall next to Blackwater Chapel in Cornwall was lit by paraffin lamps. As the children were ushered into the room they were told that they were about to meet some families who would look after them. Frank said, “I doubt whether the majority of us had ever travelled more than a two-penny bus ride from home and here we were, in a part of the country where everything seemed so different.” They were fed and then placed in family groups for inspection by the gathered crowd who Frank remembers as, “curious looking people dressed in country clothes, mostly small and speaking a strange language”. The proceedings were directed by the headmaster of Blackwater School, Mr Whale, who Frank and John would soon get to know very well. Frank recalled, “It felt like an auction and in turn, the ‘lots’ were taken to a table in a corner of the room and then spirited away to the homes of people who had agreed to house ‘these children from London’. John, myself and a couple of other boys were left unselected for what seemed like hours but despite that, no explanation or words of comfort was given. We later learned that there had been a general reluctance to choose the older boys because of the probable financial burden on poor country families who had to provide full board and lodging to lads who would probably eat them out of house and home. From memory, families were paid about four shillings a week for each child. There was also the risk that the bigger boys would prove difficult to control.”

Eventually, after much discussion, Frank and John were introduced to an elderly, well-dressed and nicely-spoken couple, Mr and Mrs Woodall; he was the Truro postmaster. Both boys left with them and walked some distance to their small bungalow at the top of Blackwater Hill. It was a temporary arrangement and during their few weeks there, Frank became convinced that this well-intentioned couple who had kindly taken them under their roof had never looked after young boys before.

One day, Mr Whale and a teacher from Perivale School arrived at the bungalow and the two boys were taken back to the chapel for another meeting. There were other children there, all unhappy and totally bewildered. Frank recalled, “Mr Whale was struggling to deal with the situation. Discipline was a problem with some of the evacuees and they and their hosts were clearly not getting on. A few children had run away, some had been badly treated and others were frightened and home sick. Mr Whale was a Welshman, a bit fiery and quick to transmit his frustration to an easy target – the children. He now had to try to re-house them, I suspect not for the first time. As before, there were people there to look us over as though we were sheep in the market, waiting for the bidding to start.”

A few hours passed and Frank and John were still waiting to be chosen but this became increasingly unlikely until it was decided that they were to be split up. John was to live with a Mrs Richards in Threemilestone, between Blackwater and Truro, while Frank had to wait a little longer to discover what was to happen to him. It was late evening, wintertime and the paraffin lamps in the hall had been lit. For Frank, it must have felt like being the last to be picked for a football team only much, much worse. At this point, one of his school friends walked into the hall. Mike Aylett had been placed with the Sandoe family but had to leave because they had subsequently decided that they could not manage another young person having taken a couple of others some months before.

People continued to wander in and out of the hall and Frank recalled that they all seemed to be looking but not “buying”. Eventually though, Mike was chosen by a farming family called Hoskins and as things turned out, these two boys were to see a lot of each other over the next three years. With Mike gone, Frank was once again the only child remaining in the hall. We can only imagine his feelings. Perhaps he had given up hope of finding a home that night when suddenly a short, round-faced man entered the hall. He was unshaven with small eyes and hairy ears. He wore a cap, brown Harris Tweed coat, large jodhpurs, leather leggings and boots coated in cow muck. Frank said, “He had the largest pair of hands imaginable and a smile that stretched from ear to ear. I don’t think that he spoke to any of the officials, he just picked up my belongings, said something in a language that I didn’t understand and took me outside to his horse and cart. It was raining and in an attempt to keep me warm and dry he covered my legs with a sack and placed another on my head. A paraffin lamp hung on the side of the cart and he said something like ‘giddy-up’ to the horse and away we went into the darkness. It was a long drive into the unknown with a man trying to speak to me in a strange language and a horse that farted every few minutes; it smelt like nothing on earth. We were bumped up and down for what seemed like hours but if I was frightened then I don’t remember being so.”

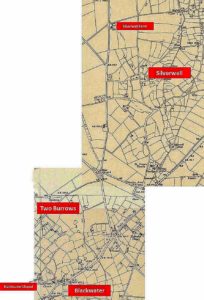

The long and winding road from Blackwater Chapel to Silverwell Farm

The long and winding road from Blackwater Chapel to Silverwell Farm

They eventually slowed and pulled into a farm yard. There were some large buildings and they drew to a halt in a barn with straw piled high. The man’s manner convinced Frank that he was safe and he was helped down from the cart. The harness was removed from the horse and it clip-clopped across the yard and into a building to join some other horses which were all “farting and blowing”. The man led Frank into the house where they removed their top clothes which were wet through. From there they went into the large kitchen and Frank recalled that the experience of entering this room has stayed with him ever since. He said, “I look back in total amazement. It was dimly lit and on the back wall was a massive cast iron range with all manner of pots and pans bubbling away. There was an old man asleep in a rocking chair; he was covered with a blanket despite the heat from the fire. There were three women, one about six feet tall, another tall and fat and wearing a hat and the third, the lady of the house, was short and fat with Eton cropped hair. She was called Beatrice and her tanned face was full of smiles. To complete the scene there were also a couple of cats and dogs. Mr Chapman, the man who had brought me from Blackwater Chapel, introduced me to the others as ‘The Lunnener’. Apart from that I couldn’t really be sure what he said. They were all smiling but I sensed that they were as nervous as me. The lighting, such as it was, came from some fancy paraffin lamps, some placed on the table and others on various pieces of furniture. One or two of the lamps smoked badly and I later learned that it was because the wicks needed trimming.”

“The room had the largest table that I had ever seen and it was groaning with the weight of food. There was meat, vegetables, fruit, pastry, jugs of cider, milk, tea and what I later discovered, was Cornish cream. I was hungry and I ate my full but I couldn’t match the appetites of the others. The meal was accompanied by endless chatter which I later concluded was a mixture of the Cornish and English languages spoken in so broad a dialect that it was impossible for me to understand. One word that I do remember was ‘please’ instead of ‘pardon’ which added to the confusion when they spoke to me.”

Frank had no idea what time he arrived at the farm nor at what time the meal finished but he had no doubt that by the end of it he was being welcomed and accepted as a member of their family. He said, “This was apparent for the entire time that I lived in Cornwall”. The meal over, they all continued to talk for some time but about what he couldn’t be sure. It was late and Mrs Chapman lit a candle and took him upstairs. There were four large bedrooms and a huge landing with a window from which he could see some twinkling lights in the distance. She indicated that one of the bedrooms was where he was to sleep and he undressed, put on his pyjamas and washed using a large, decorated china jug and bowl. He was then introduced to the most important item in the room – a huge two-handled pee pot with floral decorations. He said, “It was beyond belief, I had never seen anything like it; I was told how and when to use it. She placed it under the massive bed, removed the top blanket and took out a copper warming pan. I climbed in, blew out the candle and was soon asleep. It had been an exhausting day.”

Frank awoke to the unfamiliar sound of farm animals. Mrs Chapman appeared and after a short while, he joined everyone in the kitchen where the table was again loaded with food. A couple of young men were already sitting there, they were farm labourers and for the next three years he was to live and be good friends with them.

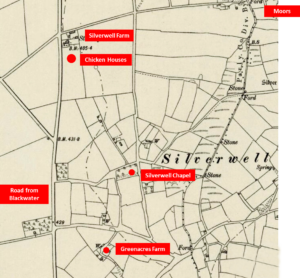

Frank commented, “I had come to live at Silverwell Farm, in the very small hamlet of Silverwell. I discovered that Mr and Mrs Chapman were without children and it must have been as difficult for them as it was for me. There was clearly empathy between us, however, and that felt good albeit we had only known each other for a few hours.”

Frank discovered that the light that he had seen from the landing window was another farm, (also called Silverwell Farm but later Greenacres Farm) (2) where his friend, Mike Aylett, was living and that provided him with some comfort. Some way to the left was Silverwell Chapel, a place that was to become very familiar to him, and immediately in front of the house was a field containing chicken houses. They held about 500 free-range birds and were to become like a second home to him.

Silverwell Chapel where Frank attended Sunday school and services

Silverwell Chapel where Frank attended Sunday school and services

The front room appeared to be not in regular use as the furniture was covered with sheets to protect it from the sun. At the rear of the house was a covered area where there were large jugs that had been filled with water by a pump; it was a ram pump and was located on the small moor, about a mile away. He learned quickly that the absence of sound from the pump meant that no water was being delivered. In that event it was necessary to race down to the moor to prime the pump.

The lane to Silverwell Moor

The lane to Silverwell Moor

The whole farm was reliant on this supply although some was also collected from rainwater. Coming from London, Frank found it amazing how the community could function without mains water, gas and electricity. Considerable effort was required just to keep the farm provided with water and although rainwater could be collected, storing it in a drinkable condition was a real problem. The covered area led to the dairy, a room about ten metres square and scrupulously clean. On one wall was a hand pump which drew water from its own well for use in the hand-operated milk cooling system. The shelves there were loaded with bottled fruits, vegetables and fresh eggs graded, boxed and ready for collection by Roberts and Son of Blackwater. In one corner of the dairy was a hand-operated centrifuging machine for making butter and cream. Cornish cream was derived from the milk which was placed in a bowl on the kitchen range, allowed to get hot (scalding) and then cooled in the dairy; the thick cream was then ladled off. Enormous chunks of meat hung from the beams, some smoked or salted, and a few chickens were on the table ready for the oven.

“My introduction to Silverwell Farm seemed to go on all day but eventually we left and set off for some fields about a couple of miles away, to a place called One Burrow where Mr Chapman’s bullocks were grazing. We walked these animals back to Silverwell Farm and soon, they were on their way to Market. In that first day it was not possible to understand what was in store for me but I do remember that someone from the chapel and the school called to see the Chapmans and they were told that the ‘Lunnener’ was staying. As things turned out, I stayed for three years.”

Frank with some of the beef cattle

Frank with some of the beef cattle

“The toilet facilities were primitive. During winter, at night, you lit your paraffin light, put on the appropriate clothes and ‘legged’ it to the two-seater. You hung the lamp on a nail, pulled the door shut, took off as few clothes as possible and sat on the damp, cold wooden seat. The place left nothing to the imagination as I was often joined by one of the adults who came in to share the two-seater. With the wind inside and out, coupled with the rats and mice, it was an experience I have never forgotten.”

The wireless (radio) in the house was powered by a battery and an accumulator (a large wet powered battery) which needed charging from time to time by the visiting “radio man”. Frank recalled, “It was only used for the news and was turned on at 7.00 am and 9.00 pm to check on how the war was progressing. With no television, radio or any petrol for social motoring I would be out with the adults taking in the countryside and appreciating nature. One summer afternoon we were in the fields when we spotted some aeroplanes, they turned out to be German. We were at Two Burrows, another part of the farm about six miles from Truro, and I can remember the explosions from their bombs. Two days later we heard it reported on our radio. News didn’t travel fast and the battery and accumulator powered wireless was used sparingly.”

Harold Chapman referred to Frank as “Boy” when they were at home but when they were out or in company, it was Frank. Mrs Chapman invariably called him “Me ansome”. That was her name for most people, even the horses. Frank called her Auntie Beat, short for Beatrice, which is what she preferred, and Mr Chapman was always “Boss”.

There was no school for the first few weeks of Frank’s time in Silverwell as the area was so full of evacuees that special arrangements had to be put in place. Eventually, he attended Blackwater School but in the three years he was in Cornwall, he reckoned that he didn’t receive the equivalent of 12 months schooling. It was a three-mile journey to Blackwater and this had to be made on foot or occasionally, on horseback. The horse was put in a local field until it was time to leave and on the way home he brought in the cows for milking. “In truth,” Frank commented, “my schooling really began and ended on Silverwell Farm and the time that I was there was some of the happiest days of my life”.

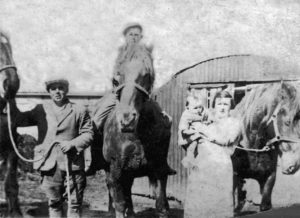

Harold Chapman holding Rose’s reins, Frank astride Lofty, Beatrice holding a neighbour’s child and Topsy

Harold Chapman holding Rose’s reins, Frank astride Lofty, Beatrice holding a neighbour’s child and Topsy

For this town boy there was much to learn about farming but he quickly adapted to this new way of life and became a great help around the farm. He was introduced to milking: how to wash the cows’ udders and milk by hand. About forty cows were milked twice a day and the milk had to be strained, cooled (there were no refrigerators), poured into churns and collected each morning by the Milk Marketing Board lorry. The churns contained ten gallons of milk and weighed about 140 pounds. They had to be lifted onto a platform or milk stand which had been built to the same height as a lorry so that the driver could roll the churns onto his vehicle. The farmers were responsible for maintaining the quality of the milk and considering the primitive facilities, that was difficult. Harold Chapman’s cousin, Gordon Chapman, worked there when there was a need, especially in the summer and Frank enjoyed his company.

The Chapmans kept prize bulls, sheep and a stallion whose “services” were “sold” for breeding. Other stock-holders brought their female animals to mate with them so enabling them to produce better quality animals for their own farms. Frank occasionally assisted Harold in ensuring the animals mated correctly. The fees were paid and recorded just in case the females failed to catch (become pregnant) in which case Harold Chapman offered another chance to mate free of charge. Frank recalled, “I had to keep my wits about me as some of the farmers tried to work a flanker by insisting that their animal had not mated properly. They then substituted another one to try and get a free mating. On the one occasion that my mother visited me, and at the same time take my brother back to London, she saw me helping the bull do its job. She had forty fits and wanted to take me home and away from such activities. For me though, it was all a part of my job and I also had to help animals give birth, castrate them, give medicines, shear sheep, clean hooves and clear infections like worms and fly blows. Docking tails [cutting] may seem cruel but it meant less muck on the rear of the animal and less chance of infection and maggot growth. Ringing pigs on the snout was also necessary as it stopped them from tearing up the ground. I was also taught to catch rabbits, either with ferrets and nets, dogs with guns or with gin traps. The ‘gin,’ was a set of steel jaws that were spring loaded with a pressure plate about three inches square set in the centre of the jaws. The jaws closed when the plate was depressed. The gin was set at night where rabbits where known to pass. It was hidden under some soil and grass and the weight of the rabbit was sufficient to spring the jaws and trap the rabbit by its legs. The poor rabbit would be in the trap until found next morning; not a nice death but the meat was needed, especially when money was short. We also had a side-line selling them to the airman at RAF Perranporth.”

There was a major fox problem at Silverwell and having lost chickens and young lambs during the late winter and early spring, Harold Chapman spent a lot of time trying to shoot the culprit. Then, one evening, he spotted a fox coming through the hedge and realised that this was a regular run for him. The following day Frank set a gin trap in the run and to his amazement, he caught the fox.

Frank had to spend a lot of time with the chickens and reflected, “To have the opportunity to place eggs under a broody hen and see them hatch was amazing. The eggs were turned by hand each day to ensure that they received regular heating. We used paraffin heated battery boxes for hatching out chicks by the hundred which were then sold to other farmers. For a town boy to be involved in this was magic, I was revelling in this country education at the ‘University of life’.”

Frank with cart horses Rose, Lofty and Topsy

Frank with cart horses Rose, Lofty and Topsy

Harold Chapman was acknowledged as a “Heavy Horse Man”. Frank was taught how to handle them and he grew to love working with these gentle creatures. Such was the attention he received that Frank became convinced that Harold and Beatrice had taken to him as a son. He said “I loved it. I had an old cob hitched to a hoe and found myself weeding swede, sprouts, mangolds and cabbage; goodness knows how many miles I walked. There were compensations too as some of the summer jobs meant that you were working a machine, cutting and raking hay or even ploughing when three horses would be used; I was surprised how I managed to work big horse teams.”

Frank recalled being taught to use a fiddle – an old-fashioned seed sowing machine mostly used to sow grass and linseed. It was a canvas bag hung from the neck on a cord and below the bag was a circular tin disc about the size of a dinner plate. It was operated by a piece of yew branch like a violin bow. A cord was looped around the stem of the disc and attached to the bow. The bow was moved in a saw like movement and the disc then rotated and dispersed the seed which had fallen on it. He said, “I had to walk up and down the field in a measured way filling the bag when necessary until I had fiddled all of it. A horse and chain harrow was then pulled across the field to bury the seed.”

Summer time on the farm was a complete eye-opener for Frank. He said, “The grass was cut by reaper [grass cutting machine] pulled by two horses. The cut grass, which would eventually become the hay, was turned by hand or by machine to allow it to thoroughly dry. It was then loaded onto a waggon and taken to where a rick was to be built. As the rick grew in height a man shaped it so that it did not collapse in the wind or allow water to get into it. Harvesting meant all hands on deck; there were differences in times of ripening of the various cereals and the biggest problem was in the weather patterns, plenty of sunshine meant ripe, sweet corn or maize.”

“Most of the work was carried out using the horses. That was until Boss bought a Massey Harris tractor from Tom Teagle, an engineering agricultural genius who had produced the first mechanical potato digger. The tractor was an evil looking machine with large steel-lugged rear wheels; it was used for a lot of the field work. On one side was a large flywheel onto which we attached a six-inch wide leather belt to drive the corn grinding machine. Once a week a few tons of corn was ground and it was not long before we were crushing corn for other farmers. They brought their sacks of grain to us and we would mill and bag it for them to use or to sell. The use of such machinery took so much of the heavy work out of farming although it didn’t seem to reduce the workload much. Being able to grind his own grain enabled Boss to buy and feed more beef animals although to do so he had to rent additional fields. Silverwell Farm was recognised as a place where wheat grew particularly well and the grain was in great demand by the bakers for bread making.”

Tilling the fields using the tractor meant that potatoes, brassicas and cereals could be planted much quicker and the time taken in cutting the corn, turning it and binding it in sheaths was shorter. Frank commented that speed brought its own problems and in the early days, hay and corn was sometimes ricked when too damp increasing the risks of it heating up and catching fire. Such fires, during wartime and with RAF Perranporth close by, were not a good idea as the smoke may have attracted enemy aircraft. Both Harold and Frank loved the horses and despite the use of the tractor, they were not abandoned altogether and continued to be used for lighter jobs.

“I was amazed how much food and drink was consumed at harvest time. In the evening, when work was finished for the day, the men stripped to the waist and washed under the pump. They were paid for their day’s work and then went into the kitchen where Mrs Chapman, and maybe six other women, had prepared the food. They sat down and the feasting began in earnest. There were pasties by the dozen and so much other food, it was as if it was their last supper. It amazed me to see people eat so much. Then the singing and the stories began and this went on for about an hour – until supper time! Some of the men slept on site putting a couple of bran bags over the sheaths and kipping down while others walked or cycled home. Despite the hard work they prayed for sunshine the next day as that meant another day’s pay. Boss usually employed Carlyon’s threshing machine and it took five or six days to clear the work; many of the men moved from farm to farm to help with the harvest. The dowst [chaff] was covered each night as apart from being unpleasant, it contained a lot of weed that would otherwise have been blown around in the wind. We had an abandoned mine shaft in one of the fields and it was tipped down there as quickly as possible. This mine shaft was also handy for disposing of other stuff. There were a number of shafts in the district and I hate to think who or what went down them for the locals were well aware of how useful they were.”

Linseed was another product that was grown and harvested once the Chapmans were appointed as a grower by the Ministry. This very fine, oily, heavy seed could not be planted in those days with a corn seed drill but was broadcast or scattered by hand and it took a lot of man hours to till. Threshing or removing the seed from the pod was also time consuming but as so many ships were being lost to enemy submarines there was a need to grow as much produce as possible.

With summer over, preparation for winter began. The stock animals for slaughter had to be looked after and this involved moving hundreds of tons of straw bedding into the various houses. The better the animals were fed and cared for, the better the return on them would be. Tons of cereal was milled each day and all of it had to be hand fed to the animals. In fact watering, feeding, and bedding was all done by hand. Moving around the farmyard in winter was difficult especially when the rain was heavy and the gales severe. In addition to wearing reasonable rainwear, a jute bran sack was pushed corner to corner to form a pointed hood and this was placed on the top of the head with the point at the top in an effort to keep your head and shoulders dry. When the sack was wet you simply looked for another one. Frank said, “The workmen wore this form of rain protection when working in the fields and it was quite common to see a farm labourer with his boots repaired with a piece of rubber tyre tacked on to the soles.”

A typical sack hood worn by farmers

A typical sack hood worn by farmers

“Life on the farm was busy at most times of the year but in winter, with the dark evenings, it began at first light and didn’t end until last thing at night. All of the animals had to be checked and bedded down and with only a paraffin lamp to illuminate your way there was an eerie feeling that you were being watched by the owls, bats and rats. It was an experience that remains with me. The last job of all was to check the horses; you were expected by them and made welcome. The moment that you were at their side they would muzzle you and search your pockets for any tit-bits. It was a part of my job to clean the horses, they were washed, their hooves checked and if new shoes were needed then Arthur Moyle, the local Blacksmith and grave digger, was called in. He dressed the hoof, replaced the shoe and the horse was ready for work again within hours. Occasionally, he would do this during an evening especially if the horses were working in pairs and were needed first thing the next day. Boss was very fond of the horses and woe-betide anyone if they came on a bit strong with them. Harold Chapman would really dress them down and, interestingly enough, the horses never seemed to forget and would await the opportunity to catch the person with their head or hoof.”

Wednesday was market day at Truro, a special day for most of the farmers and their families. They went there to sell their cattle or perhaps to buy new stock. The men from the Ministry were usually there and this provided the opportunity to meet them, often in the pub, to have a moan or to obtain the necessary forms and certificates to move or sell cattle. Agreeing what was to be grown for the war effort and filling in the necessary forms was the farmers’ nightmare. Another important job for Boss on market day, apart from his “annual” haircut, was to buy clothes. Frank recalled that Beatrice would travel to Truro on her own and Harold would meet her to do some shopping – usually under duress. He would have travelled with his brother in his cattle lorry.

Harold Chapman’s brother, Arthur (left), at Truro Market

Harold Chapman’s brother, Arthur (left), at Truro Market

“Occasionally I would go to Truro on market day. Auntie Beat and I would wait outside our gate for Mr Thomas and his charabanc [bus]; it ran once a week to the local towns. The vehicle wheezed and snorted its way to Truro stopping every few minutes to pick up passengers. Live and dead chickens and ducks were put in the back of the vehicle while rabbits, the occasional turkey and trays of day-old chicks were inside, often on someone’s lap. When all the seats were taken the children had to stand. On one occasion, and I had not been told this, Auntie Beat was taking me to the family tailor for a new suit. It was a brown pin-stripe with long trousers complete with matching waistcoat, shirt, tie and a pair of best black boots that had to be polished for Sunday school and services at Silverwell Chapel. That suit attracted a few ribald remarks from the farm labourers but Auntie Beat soon shut them up. I was given a silver pocket watch and matching chain to hang from my waistcoat pocket and from the chain hung a pendant of a bull. It was a wonderful present which really did show how much they thought of me.”

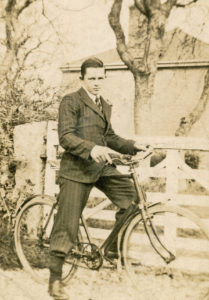

Frank in his new suit

Frank in his new suit

“For Christmas that year Mr and Mrs Chapman bought me a bicycle. Then, with transport, I could ride to school, bring the animals in from the outlying fields and even meet up on the odd occasion with Gordon Chapman. He was about twenty years old and often cycled from his home in Chacewater to a cinema in any one of the local villages.”

Frank with his bike, another present from the Chapmans

Frank with his bike, another present from the Chapmans

Beatrice Chapman (Auntie Beat)

Beatrice Chapman (Auntie Beat)

There was no telephone at the farm so communications had to be by post, telegram or by visits. Frank wrote home perhaps twice a month and his parents replied with letters which were usually quite short. “I can’t remember the contents but I would always show them to Mr and Mrs Chapman. I do know that they also received letters from my parents and that there appeared to be some difficulty and unhappiness at home.”

“It was March 1943 that I realised that something was wrong. I had noticed Mrs Chapman in tears on a number of occasions, usually after some strangers had left the house. I was told later that they were social and school workers. Then, one day, the Chapman’s relatives came to the farm and there was a discussion between them, Mr Whale and my teacher. Eventually I was called into the front room and in a very emotional scene was told that my mother was coming to Silverwell to take me home. I had never been as happy as when I was living with Mr and Mrs Chapman and I flatly refused to go. From what the Chapmans told me later there had been talk of them becoming my guardians for the war period but my mother had refused. She had detected the resistance and had formally requested the Evacuation Authority to arrange my return. There was nothing that I could do. I was hauled back to London and this forced return created a barrier between me and my parents which was to last for many years.”

“My memory of my return to London is very vague and it was only when I was later given a letter by the Headmaster of Selbourne Boys School at Greenford that I became aware that I arrived back in London around March 1943. I was fortunate that he realised that I had spent little time at school in Cornwall and he pushed me hard to learn. He must have done a fair job for within twelve months I had left school, found a job and was earning a living.”

Returning to Perivale at this time in the war, Frank experienced the raids by Adolf Hitler’s Doodlebug bombs. School buildings and houses provided little protection from these and Medway Parade, Just a short distance from his school, suffered a direct hit which killed many people. In the evening of the same day a bomb hit the school playing fields. The bombs were jet propelled, pilotless aeroplanes. They were supposedly aimed at a target but if they ran out of fuel, the engine stopped and the bomb glided on and often dropped onto civilian targets killing many people.

There was a lot of tension in the Long household and Frank acknowledged that he often added to the difficulty. “For the years that I was away in Cornwall my parents had lived, as many other Londoners did, in fear of the bombing and with a shortage of food and money. Each day, my Dad left around five in the morning and cycled to work in an area that sustained a lot of daylight air raids. He arrived home late in the evening and he and my mother regularly spent their nights in the air raid shelter. From the time of my return I detected that conversation between my parents was difficult. They had problems with their respective mothers and the fact that my brother, John, had to spend a lot of time in hospital was a strain. My mother found that she could not handle me without resorting to some physical restraint and although I never resorted to violence, the fact that I was as strong as most men, frustrated her. She was very fond of using the famous copper stick until she found that I could and did defend myself. My poor old Dad went through the mill for he was a man who preferred peace and quiet after a day’s work. My mother, too, was not happy that I wished to continue my relationship with Mr and Mrs Chapman and tried to stop me writing to them. I refused and continued corresponding up until the time of Harold Chapman’s death.”

About 18 months after Frank’s return to London the Chapmans wrote to say that Beatrice had given birth to a son. Frank recalled that Beatrice had always seemed reluctant to talk about such matters but it was clear that she was delighted to tell him the news. The baby was named Eldred and now, in 2019, Frank is still in touch with him. A few years later the news was of a much more tragic nature. Mrs Chapman had been in the milking parlour and was knocked down by a cow whilst releasing it from its neck chain. The cow trod on her neck and within hours she was dead.

Frank reflected on his relationship with his mother which even after so many years, still troubled him. “I really don’t know why my mother found it difficult to keep the peace but arguments flared up all the time as so many of my school pals later recalled. Perhaps what we had been through in this terrible war contributed to the strained relationship between us all. Perhaps it was all too much for her and she needed to release her wrath on someone. Perhaps I was her scapegoat.”

Epilogue:

Frank in 2019

Frank in 2019

“When I was 17 years of age, and later in my 20s, my school pal, John Wade, and I cycled from Perivale to Silverwell and camped at the Farm. It was a 560-mile return journey on a heavy BSA bicycle loaded with blankets, cooking equipment and a tent. Later, I took my wife, Evelyn, there and Harold Chapman could not have been more receptive. Unfortunately, Evelyn couldn’t understand much of what he was saying but she enjoyed meeting him.”

“Reflecting on these memories reminds me how lucky l was to have been placed as an evacuee with such caring people as the Chapmans and in such a beautiful place. I hope that this is a reminder to us all that the Cornish people, amongst many others, took on a great responsibility in fostering so many young evacuee children and for that l thank them.”

(Frank Long 2019)

Cover Photo: Silverwell Farm

End notes:

- “Silverwell Farm” was previously named “Rogue’s Roost” and, before that, “St Day House”. Harold Chapman moved there in 1938 and it was probable that it then became “Silverwell Farm”.

- “Greenacre’s Farm” was previously named “Silverwell Farm” and for a while there were two locations with the same name. It seems to be during the early 1950s that it was renamed “Greenacre’s Farm”.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history and is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and a sub-editor with Cornish Story: an Institute of Cornish Studies initiative.

Wonderful story. It must have been very frightening and strange for children from the cities. Many of them were very homesick and some not treated very well.

Even though I was born just after WW2, I can recall much of Frank’s experiences of farming during those times and for some time after too as told to me by members of my family and friends.

My partner’s father, also a farmer during the war, was a food officer during that time, so my partner can remember such farming practises too. My partner’s father had POWs helping on his farm, one of whom came back to visit from Germany in the early 1950s.

A wonderful story of the life of children who learned life in Cornwall. A happy life, with lots of family chatting and the boys grew and learned the true life. Wonderful, a time that isn’t life sadly now, and today’s children don’t have the learning of the life that had meaning, joyus

A great read Tony and really enjoyed Tony!!