In this article, Tony Mansell turns to the gunpowder manufacturing industry of the 19th century and looks at the process involved, and the pain experienced when things go wrong.

Gunpowder was invented in China, probably in the 9th century, and its potential for warfare and for more peaceful purposes was quickly realised.

Opinions vary regarding the date of the first use of gunpowder in Cornish mining and quarrying but by the beginning of the 19th century, about 4,000 barrels of gunpowder per annum were crossing the Tamar from England. Frank Nicholls and Henry Gill first saw the potential for a local gunpowder mill and opened one at Cosawes Wood, near Ponsanooth, and in 1809 it was said, “If gunpowder could be manufactured locally and sold at a reasonable price, good business would be had”. (1) It was an immediate success and it encouraged the Fox family to set up a larger plant in nearby Kennall Vale. In time, other such plants opened across Cornwall but none on the scale of the one at Kennall Vale.

In 1812 there was a huge demand for the material and it made the venture successful from the start.

It is suggested that the Fox family were involved at Kennal Vale and that Benjamin Sampson was appointed manager. He had been a carpenter at the Tresavean Mine in Gwennap and later, an agent of the Perran Iron Foundry at Perranarworthal. However, John Hockin of Swanage in Dorset, writing in the journal of the Cornwall Family History Society, wished to clarify the situation.

“The Fox family had nothing to do with the Kennal Gunpowder Mill Co. Benjamin Sampson was granted licence to build the mills, which he did in 1811/12. With his partners, John F Devonshire and Edward Allen, he operated it. The definitive account of the Fox’s Perran Foundry is by W Tregoning Hooper. In it he states that Benjamin Sampson established the Kennal Vale Powder Mills. In his comprehensive account of the Fox family and Perran Foundry there is no suggestion that the family were involved in Kennal Vale. Richard Lanyon was the long time manager of the Mills and in 1823 became a minor partner, he confirms that Benjamin Sampson founded the Mills in a letter to the Mining Journal 1880.”

John claims that a misunderstanding about the Fox family involvement has arisen and been perpetuated.

John continued:

“Before Benjamin Sampson could obtain his licence from the Justices he was required to give notice of his application in the locality and especially the Parish Church authorities. The law required that his Mill could not be built, among other restrictions, in or within one mile of any town or half a mile of a Parish Church… In the notice, the applicant gives his name, address and occupation. Benjamin Sampson did this and stated that he was agent to Messrs Fox’s and Perran Iron Founders – not Agent for the Fox Family, i.e. merely someone who facilitates the sale of the company’s products. He duly served notice on the church authorities: it was not a request for permission nor was it a plea for consent. The church could object if it wished, to the Justices. They did not and Benjamin Sampson was granted his licence, built and succesfully ran his mills from 1812 until his death in 1840.”

Kennall Vale is a heavily wooded valley with a fast running river making it an ideal location for the enterprise. The River Kennall is only about five or six miles in length but its power was such that it turned almost 40 waterwheels as it made its way to the sea. Its busy waters were speedily harnessed and diverted into aqueducts, leats and launders and it worked night and day to drive the machinery. The once beautiful valley had been adapted to meet man’s needs and it was soon full of the smells and sounds of industry. The buildings were set well apart to minimize the damage if an explosion occurred. That, and the presence of well-developed trees, would absorb the blast if the worst happened.

An interesting reference to the works was made in 1824: “Farther on in Kennall Wood it [the Kennall River] turns six water wheels, some very large, and works an hydraulic machine for manufacturing gunpowder. To work this machinery the river falls 84 feet perpendicularly, and is constantly turning …”(2)

“In Kennall Vale are gunpowder mills belonging to Messrs Sampson and Co. Here are situated water-wheels constantly employed, two of which keep 14 tons of marble constantly turning, making four to five thousand barrels of gunpowder annually.” (3)

The raw ingredients for gunpowder are charcoal, saltpetre and sulphur (brimstone). The sulphur and the charcoal was ground to a fine consistency in the watermills and the saltpetre was refined to the required purity before being added to the mix. It was then loaded into barrels and taken to one of the incorporating mills where it was ground to a fine consistency. The mill stones were housed in buildings either side of an over-shot water wheel which was supplied via a leat. Once the milling had been completed the material was shovelled out and taken to the press house where it was compressed by a hydraulic ram into “press cake” about an inch thick. There is much more to the process before it could be despatched but my description of it will cease here as this story mainly involves the press house, building 42.

In 1845 the works more than doubled in size when a new factory was constructed in Roche’s Woods, adjacent to the original works. By 1860 the combined venture was employing about 50 men and utilising 50 or more buildings.

In 1864 William Shilson took over the works from Benjamin Cloak who had died and on William’s death, in 1875, his sons, Charles and David Henry Shilson became joint proprietors. J W Wilkinson was appointed manager.

Demand for gunpowder fluctuated in line with the vagaries of the mining and quarrying industries and with the requirements of the munition factories in times of war but business was good and remained so until the introduction of dynamite and gelignite.

The Kennall Vale Incident

Across the years, serious accidents did occur at Kennall Vale but considering the dangerous nature of the work, perhaps not as many as would have been expected. The company seems to have had a high regard for safety. This was, no doubt, both for the safety of its employees and for the continuity of work which would inevitably have been affected in the event of an accident. At the induction of new employees, and as an ongoing practice, the dangers were spelt out to the workers. No doubt there were signs posted but it was also delivered verbally as most of the men could not read. To prevent them carrying matches their clothing had no pockets and to avoid sparks, their boots did not contain nails. There were foot troughs at the entrance to some of the buildings where any inflammable material could be washed from their boots.

There were fatalities, however, tragedies for the families involved and upsetting for fellow employees. In this paper we are considering one of those accidents, one that took the lives of two men and had a huge impact on those left to struggle on with little or no help from society.

James William Paddy was born on the 31st May 1830 at St Just in Roseland. He married Elizabeth Job Harvey at St Allen Church and they had four children of which three survived to adulthood. After moving from St Allen, he became a farmer at Tremenhere Farm, Ponsanooth. Sometime around 1874 their eldest son, Edwin James Paddy, then 12 years-old, joined Ponsanooth Brass Band so it seems safe to assume that the family were living at Tremenhere Farm by then.

In 1878 James William Paddy made the short journey from Tremenhere Farm to Kennall Vale to ask for a job and for the next nine years he was an ancillary worker in the gunpowder manufacturing industry.

Monday the 7th November 1887 was probably like any other: James Paddy left Tremenhere Farm and set out for his day’s work at the gunpowder works.

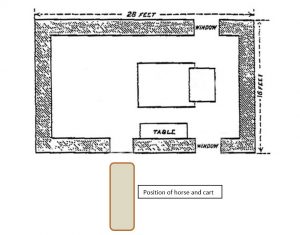

By seven o’clock he had harnessed his horse and was at the lower works, ready to make a start. He loaded three 80 lb barrels of powder onto his small, two-wheeled cart, closed the rear doors, covered it over and headed for the press house at the top of the site. It was a familiar route and the horse would hardly need guiding.

It was just after eight o’clock when James reached the press house where the operator, William Dunstan, was working. James backed his horse and cart to the entrance door and moved to the rear of the cart to open the doors.

At five minutes past eight, the village of Ponsanooth was shaken by an explosion which was heard for miles. Within a few minutes a large crowd had gathered at the factory gates, all anxious for information and dreading the news that their loved ones had been killed or injured in the blast.

The manager, Mr Wilkinson, heard a noise but mistook it for an occurrence within his house. However, he quickly realised that that was not the case and what a scene of devastation greeted him and the men who rushed to help; the press house, building number 42, had been blown to smithereens. The huge blocks of stone from the walls had been propelled several yards and the roof was scattered in all directions. The press house had been built in a recess cut out of the steep hillside with a sloping bank at the rear. That, and the large blast wall, had provided some protection to building number 41, the breaking-down house.

The Cornwall Wildlife Trust location map

The blue spot marks the approximate position of the Press House, Building No. 42

- Packing House where the gunpowder was packed into wooden barrels

- Quarry

- Corning House where the mixed ingredients were reduced to fine grains

- Incorporating Mills where the saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal was ground together

- Limestone Runner Wheel which was used to grind raw ingredients

- Change House where the workers changed into woollen clothing

A white piece of granite which Neville Paddy suggests marks the spot where James Paddy was standing when the explosion occurred (Photo: Tony Mansell)

A white piece of granite which Neville Paddy suggests marks the spot where James Paddy was standing when the explosion occurred (Photo: Tony Mansell)

The explosion had involved over 1,000 lbs of powder, more if account is taken of what had accumulated under the floorboards and behind the wall panelling. William Dunstan was killed instantly. His severed leg was discovered a few yards from where the building had stood and shortly after the remainder of his body was found some thirty yards from the explosion. James Paddy was found alive and lying in a leat some fifteen yards away from the demolished press house; he had suffered severe injuries and was also badly burned. The horse appeared to have bolted away from the exploding press house having only slightly singed hair and a small cut from a piece of glass.

Wreckage of the Press House with the remains of James Paddy’s cart top middle

Wreckage of the Press House with the remains of James Paddy’s cart top middle

Dr Blamey of Penryn attended the scene and instructed that James Paddy be transported (by means not recorded but probably by horse and cart) to the Royal Cornwall Infirmary some eight miles distant, in Truro.

The Secretary for the Home Department appointed Major J P Cundell, R.A. Inspector of Explosives to report the circumstances of the explosion and he travelled to Cornwall the following day to carry out his investigations. On the same day (Tuesday), the coroner, Mr J Carlyon presided over the opening session of the inquest which was opened and adjourned until the following Thursday pending delivery of Major Cundell’s findings.

Although badly injured, James Paddy was able to give a verbal account of the event. Major Cundell reported: “… Mr Carlyon and I went to the Royal Cornwall Infirmary at Truro, and by permission of the resident surgeon, Mr Edmund Rundle, saw the injured man James Paddy. The latter was much injured, but perfectly clear in his mind, and able to tell all he knew about the accident, which accounted, however, to very little as regards accounting the actual cause of it, though his statement was valuable as negativing certain possible causes. I will deal with his evidence when I come to the consideration of the circumstances immediately preceding the explosion and of the possible/causes thereof.”

Later in his report he included James Paddy’s statement: “I came up from the lower works with a load of dust powder in the covered cart drawn by one horse, about 8.00am. I got to the press house, and had backed the cart to the door, and was going to deliver the powder for pressing. I had three barrels of powder, about 2 cwt. I was just going to open the doors of the cart. I am not quite sure whether I got them open or not. I saw no flash. I did not see inside the house at the time, for my back was to the door. I do not know what happened, but I was blown into the leat. I had on the jacket supplied by the company and my own waistcoat and trousers. I am sure I had no matches. I never carry any. I have been employed about nine years in the factory but have never worked in the powder buildings. My business was to take the powder about the factory in a cart. I know nothing about the workings of the press.”

The above statement was considered by the Inspector of Explosives to be “probably perfectly accurate” and was corroborated by several circumstances.

James Paddy languished in his hospital bed for 23 days but, on the 30th November 1887, he died of his injuries.

Major Cundell’s report was presented to both Houses of Parliament by command of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. In summary it stated that he was disposed to think that the accident arose from some fire being accidently struck or caused by:

- Dunstan at the boxes.

- In the press.

- A spark from the watch-house chimney.

He went on to say: “(c) was much the least probable and that of the others, all things considered, greatest weight must be attached to (a)”.

From this it is clear that William Dunstan was thought to have caused the explosion which had claimed his life and that of James Paddy.

The Coroner’s jury returned a verdict of accidental death and exonerated the company from blame.

William Dunstan’s wife was left a widow with nine children. It was a time when there were few opportunities to access help except, of course, by going to the workhouse.

Following James’ death, Elizabeth Paddy left Tremenhere Farm and moved to a cottage in the village. His eldest son brought his wife and baby daughter to live in Cornwall, possibly to Ponsanooth, to be near his mother.

James William Paddy was a hard-working man who wanted nothing more than to do his best for his family. As the report suggested, he was an innocent victim, someone who was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

James William Paddy was my great, great, grandfather.

One of the concluding paragraphs in the Archaeological and Historical Study by John R Smith is headed “Kennall Vale in perspective”. It talks of an industrial activity co-existing with nature in a beautiful valley where, at night, waterwheels rumbled in the darkness with buildings dimly lit by lanterns hanging from trees and on summer days, of leats sparkling in the sunshine with the horse and cart plodding up and down the paths.

Present Day Kennall Vale

The Cornwall Wildlife Trust now lease Kennall Vale which has reverted to its former state of being a beautiful Cornish valley albeit with its brief industrial past still apparent.

One of the many leats that once served the factory and which now move with much less urgency (Photo: Tony Mansell)

One of the many leats that once served the factory and which now move with much less urgency (Photo: Tony Mansell)

The busy waters of the River Kennall (Photo: Tony Mansell)

The busy waters of the River Kennall (Photo: Tony Mansell)

I will leave the conclusion to my cousin, Neville Paddy, James William Paddy’s great grandson.

“This acutely atmospheric wooded valley with its effervescent river waters, old gunpowder mills and ruins of over fifty buildings once used for explosive processing, is really worth a visit. Those who do so cannot help but hear the pleasant callings of the songbirds accompanied by the cascading waters of the River Kennall. But if you linger here and listen awhile, you may think you have heard voices amid the sounds of those rushing waters. I can assure you that you are not alone for many have heard such voices before you. Closer to the ruins of the eight mill-houses you might even hear whispers that pass like breezes through the tree canopies of Roches Wood.

Whenever I walk along its paths, I try to imagine what it was like working here every day in the mills or in powder processing buildings scattered about as though thrown amongst the woodland trees. Men, woman and children have dallied, joked, laughed and cried here when going about their dangerous daily work. I have often asked myself – do spirits remain here along the valley basin where river waters tumble over stones? Or are they up there amongst the tall ruins of the powder mills and their silent rusted wheels – giant incorporating mill wheels that were water driven and which fell silent close to 100 years past?” (4)

- “Blast from the past” in “My Cornwall” by Pete London.

2. “History of Cornwall” 1824 by Hitchens and Drew.

3. “Penaluna’s Survey” of 1838.

4. “Kennall Vale Gunpowder” (Cornwall Family History Society Newsletter) by Neville Paddy, James William Paddy’s great grandson.

I am grateful for the considerable contribution to this article by my cousin, Neville Paddy, and for the information taken from “The Kennall Vale Gunpowder Company, An Archaeological and Historical Study” by John R Smith 1984 for Cornwall Trust for Nature Conservation.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history and is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and a sub-editor with Cornish Story: an Institute of Cornish Studies initiative.

What an incredible story and so well researched.

Thank you for your comprehensive story of Kennall Vale and its unfortunate victims. The fairytale setting of the valley belies its chequered past. Thank you for sharing your family’s personal story.

Thanks for your kind comments Rob.