In this latest article in the series covering the history of Cornish hostelries and ale houses, Kiera Smitheram takes us to Penzance and to a tavern teeming with history, heritage, and heart.

Penzance is the most westerly town in Cornwall, on the foot of Britain. It is situated in the shelter of Mounts Bay. The town faces south-east at the westerly entrance to the English Channel. My family’s roots are buried beneath this town: the strays and survivors of the defeated Spanish fleet that attacked the town and the surrounding villages of Newlyn and Mousehole during the Armada in 1588.

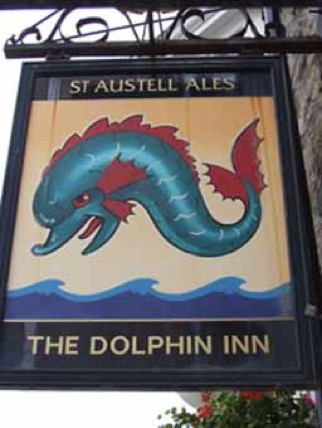

As a child I would often walk along Penzance Harbour’s promenade. From the site of the railway station I headed west toward Newlyn, the sister town of Penzance, until I reached the last building on a tight corner of Penzance harbour just before the open-air “Jubilee Swimming Pool.” The building in question was and is the ‘Dolphin Tavern’. It wasn’t until I was commissioned to write this piece that I realised how significant it was. The Dolphin Tavern is one of the most historic and as duty manager Paris said, the best pubs in Penzance. I was certainly won over as I sat at the bar tapping at my laptop, asking Paris questions as he manoeuvred like a seasoned captain in command of his ship. It looks like a ship inside too, and apparently very little has changed since it first opened apart from the addition of the usual mod-cons. The ceiling beams hang low, rigging is strung about, and the lighting is dim but welcoming. The exact age of the building is unknown, but its granite façade and structure places it somewhere in the 14thcentury. That granite stands exposed and as hardy as ever when you enter.

“It’s the atmosphere,” he says with a considered smile as I asked about what keeps bringing people back. It’s true, the atmosphere is a singular one that has been drawing locals and visitors in for over four hundred years. The Dolphin shares the title of being one the oldest establishments in the town. It is also one of the historically richest pubs in the area, together with the Admiral Benbow Inn, named after the real 17th century naval officer that inspired Robert Louis Stevenson’s fictional Llandoger Inn featured in ‘Treasure Island’ and the Turk’s Head Inn founded in 1233 after the invasion of Turkish exiles in the 13th century.

Externally very little has altered at The Dolphin but the stories of its patrons and staff has shaped its image from a small coastal ‘local’ into a hub of heritage.

Penzance has enjoyed a colourful history, being one of the primary port towns along the south coast. Even in its earliest recorded days, in the 14thcentury, it was a thriving market port, with fairs and stalls drawing in respected tradespersons and buyers alike. Many famous faces have visited and resided in the town. It is said that Sir Walter Raleigh smoked his first pipe of tobacco in the tavern. Although the authenticity of this account is unknown, it is quite believable.

Penzance has always been a historic and cultural hub. From its naval history to its invasion of pirates following the Spanish Armada the town has seen its fair share of action. In 1595 the tavern was used as a recruitment office by John Hawkin to recruit men to sail against the Spanish. The town was a target due to it being granted a charter for a harbour by Henry VIII in 1512. During these gruelling battles much of the Tudor infrastructure was destroyed,and the damage was not fully repaired until about 1614. King James I rewarded the newly restored town with a Charter of Incorporation, allowing it to have a mayor. This new-found trade and prosperity after such a disaster was certainly seized on by the Dolphin, being ideally located beside the harbour wall, drawing in local and international tradesmen from the sea and saving them the walk up the hill into the centre of the town.

Despite a mild down-time during the Puritan regime of Oliver Cromwell (Penzance had been a Royalist town and suffered greatly after a Parliamentarian attack) the town was revived as a thriving industrial port for the trade of tin, grain, and fish. You can still see a nod to its Royalist allegiance above the bar on a leather strap from the HMS Royalist. In 1663, after the Charter was certified by Charles II, it became a coinage town where tin was weighed and traded. This would become extremely important during the industrial revolution.

The town’s history has even inspired operas, most notably by Gilbert and Sullivan in the farcical ‘The Pirates of Penzance’. Although the violent destruction of homes and livelihoods is absent from the swashbuckling story, it is the fact that they chose Penzance as the primary setting that shows what an influential town it was to seafaring and trade.

When the Napoleonic War broke out and the upper classes were forced out of their European villas they chose to escape to Cornwall where they could not only take in the fresh sea air, but also immerse themselves in the rustic and brooding atmosphere of the remote villages and rugged coastline popularised in the newly emerging form, the Novel. A pub like the Dolphin would have fared well with literary fans.

The 19th century also saw the town’s biggest growth, with the additions of Clarence Street, Victoria Place, and the famous Egyptian House as well as the train station. In spite of all the innovation, the Dolphin stood resolute and untampered as a new modern age was born around it. Europe’s very first dry dock was built in 1834 just a few yards away, bringing in more international visitors than ever before. When the town turned into a health resort in the mid-1850s, including the construction of the promenade in 1844, it allowed the tavern to not only cater to the dry dock workers, businessmen and traders but to the leisure fraternity too. An account given also says that the local entrepreneurs at Holman’s allowed shipments from Norway to dock in their Penzance and Marazion locations to transport wares into Cornwall instead of trying to navigate the narrower North and South Quays of Hayle.

The Dolphin also had the added bonus of being located next to the old harbour office, which has since been demolished to make way for a road. Being located near the harbour also allows it to attract those who have just returned from the Isles of Scilly, or those in need of Dutch courage before the voyage. Very little changed during the 20th century, the pub can be seen in many home film reels protruding onto the street corner in panoramic shots of the historic harbour side.

Paris pointed me in the direction of a room to the left of the bar, furnished for the upcoming lunch rush. The walls display old photographs of the town and posters for various products and services, some of which I had never heard of. These are some of the reminders of Cornwall’s industrial past that began to disappear as early as the 1860s and 70s, when copper and tin began to crash. The place wears its history proudly like tattoos.

He then directed me to the central table; long and made of dark polished wood, nothing out of the ordinary.

“We call the room underneath ‘The Hanging Room,’ and it’s where we keep Rich and Siobhan’s old furniture.” He laughed at the slight absurdity of the room’s pet name. Rich and Siobhan are the current landlords and have been for the last 13 years. Though I did not get to meet them I was assured that they were as welcoming and friendly as landlords could be, and had taken to their lifestyle amiably.

He explained that during the winter months the room next to us had been the courtroom. These days, dining chairs take the place of the bench, and the tyrannical Judge Jefferies who would preside over the cases has been replaced by the locals in the midst of a game or a chat over a pint. The spot where the pool table sits used to be the drop hatch for the indoor gallows, and below it was the dungeon. As grotesque as this all sounds, Paris remarked that it is one of the reasons that people come to visit. The tavern even boasts three resident spectres. Although they are rarely seen, past staff and landlords have made accounts of a young, fair haired man who was supposedly killed in a fight. He appears at the foot of the landlords’ bed. There is also a young Victorian woman who floats along the bar and disappears through a wall, and an old sea captain known as George, wearing a tricorn hat.

I asked him if he felt that the presence of the ghosts was at all detrimental to business, he laughed and said it was quite the opposite. People seemed to be drawn to the idea of it. Places like the Jamaica Inn and Bodmin Jail have embraced their grizzly past to great acclaim, but the intrigue of the Dolphin’s spectres come from them appearing in such an unassuming place. Actor Chris Barnicoat recalled an experience he had at the Dolphin during a ghost hunting trip into the cellars. He remarked that once inside he could sense that chains had hung from the ceilings and walls. His senses were correct even though he had never been in the room before or known anything about its history prior to his visit. Even the supernatural inhabitants are keen for their history to be preserved, it seems. Of the 3.4 million visitors who come to Cornwall each year, there are always those who seek out the residents of the past as well as the friendships of those in the present.

With such a reputation, I asked Paris why the present owners wanted to take it on. He told me that they wanted “a piece of Cornwall of their own”. This idea of taking on Cornish pubs has seen a resurgence in the last couple of years – some have turned them into more upmarket gastropubs with bright, clean interiors could be anywhere. The Dolphin has changed very little after centuries of changed hands (aside from new locks, WCs, and Wi-Fi) and it is because of this that it enjoys many repeat visitors.

I asked him how pub culture was changing, and was it for the better or worse. He felt that having a local brewery producing fine ales helped tourists to have a truly singular Cornish experience. There was nothing wrong with modernisation, but he did not wish to lose the appeal of the old ways. I enquired if he felt that the summer and winter seasons offered different experiences for visitors. He felt that naturally people would want to enjoy the fine weather in summer and would choose to sit outside, but the quality of food and service did not change: every single guest would have the same friendly experience. Though this attitude of not liking change may seem to some as counter-productive, it has in the last few years become a very lucrative idea. The rising popularity of dramas set in the South West has seen an increase in people seeking out ‘hidden gems’ and ‘authentic’ Cornish places. The time warp that seems to encapsulate Cornwall that was once seen as provincial and unwavering has become something desirable. The idea of this Cornish culture has had scholars debating for as long as the study of Cornish has been around, but I feel that the Dolphin encapsulates the essence of it rather well. It does not feel like it is catering to any fad or dream: it is what it has always been. For over 500 years it has stood against revolutions, corruptions, and the turning tide of the English Channel. It shares in Cornwall’s welcoming and homely ways, and of its attitude of doing it ‘dreckly’. People seek the quality of ‘feeling Cornish’, of ‘belonging,’ as discussed by Bernard Deacon and Philip Payton.

Public Houses have enjoyed a long history of unity and The Dolphin is no exception. As I sat tapping I overheard a conversation between Paris and the landlord of the pub next door who had come in for a quick pre-lunch pint. Such friendly connections between rival businesses is very rarely seen anywhere else in the UK, especially in urban areas where commerce is key.

I returned a few hours later to have my lunch by which time the pub was full of hungry punters chatting happily over plates of food and cool pints. The mood had changed notably from when I had first arrived, the stillness of the morning had given way to the hubbub of lunchtime. Paris served us with the same kindness and charm as he had when we arrived, and continued to do so with each of the other guests around us. It was odd to think that my voice would become part of an ambience that had existed for so long, and would linger as part of its history for years to come. You don’t feel that a lot these days.

The Dolphin is a gem hidden in plain sight no matter what you are seeking: good food and good company – it has a lot to offer. If you can assuage your eyes from the sparkling sea for just a moment, you will spy a piece of tavern history awaiting you.

References

The Harveys of Hayle by Edmund Vale, 1966, page 324

Cornish Studies, Philip Payton (editor), 1993, page 62

http://penzance.co.uk/descrip/history.htm

http://www.localhistories.org/penzance.html

http://www.turksheadpenzance.co.uk/the-oldest-pub-in-penzance/

You can find the rest of the articles in the Public Houses, Hostelries and Taverns of Cornwall series here. You can also follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Wonderfully and wittily written, well done Kiera, lovely read.