In the first of the series on Cornish Music, Tony Mansell presents a vivid history of the world of the brass band in Cornwall.

Brass Bands were once at the heart of every Cornish community and in constant demand at the various secular and religious events. They performed a great service and almost every village and town clamoured to have its own. There was immense pride as “your band” competed against others on the contest stage and for the players there was real pleasure in taking part, a satisfaction in being a member of such an important group.

It is impossible to identify the first Cornish brass band or to determine when it blew its first note. The reason is that no one can claim to have invented the brass band, they did not suddenly appear, they evolved. One distant and rather tenuous ancestor from medieval times is the groups of musicians or village players who gathered to entertain, playing whatever instruments they could lay their hands on.

They were still being referred to as such in 1836 when, “A band of musicians headed a procession of Freemasons and townspeople from the town to Carn Brea for the laying of the foundation stone of the monument to Lord de Dunstanville”.

Another important group were those who accompanied the hymn singing. Their origin stretches back to the late 1640s when Oliver Cromwell issued an edict that church organs were to be removed and destroyed. Organs were considered to be not sufficiently pious for the Puritans and were replaced by groups of players whose purpose was to help regulate the pace and pitch of the music. Like the village players, they also played a diverse and strange collection of wind and string instruments and how tuneful a result this produced is open to conjecture.

In many areas they evolved into what was to become known as “West Gallery minstrels”. These were located in an elevated position at the west end of the churches – hence the name. Despite sharing the common purpose of providing music for the community these early bands were very different to those of today, both in the number of players and in the types of instruments played.

The military band has a history reaching back hundreds of years. It consists of percussion and wind players, both woodwind and brass. The disbandment of some military units, especially after the Napoleonic Wars, often left players with no musical involvement and many civilian bands sprang up to fill the vacuum. These players joined, or formed, reed and brass bands – the brass band’s true ancestor.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s it was quite common for reed and brass bands in the north of England and Wales to be works bands, financially dependent on the mills, factories and coal mines where the players worked. In Cornwall, however, the story was quite different. Devoid of large industry, the bands here were centred on communities – villages and towns.

Life was hard in those far-off days and the work relentless, so it was little wonder that the recreational opportunity of making music was eagerly grasped but with no financial backing the Cornish bands’ main source of income was from playing at local events.

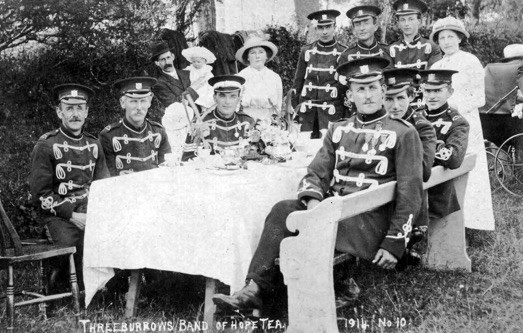

Bands were a great attraction and for most organisers it would have been unheard of not to hire one for that special event. Sadly, many of these events are no longer a part of our community life. One such is the traditional tea-treat which has now been largely confined to history.

Everything stopped for the occasion; it was the biggest event on the village calendar and of great significance to the chapel and to the community. The chosen venue may have been someone’s large garden or a suitable field. The grass was cut and tables erected for the sale of produce and the serving of food.

The schoolroom forms were placed in concert formation and as any bandsman will testify, these became harder and harder as the day progressed. The event started with a procession and each chapel or church had its own banner which was proudly carried at the front. Immediately behind came the band, followed by the children and the adults.

The route seemed endless and for most of its length there were few houses and the band played to the hedgerows with the occasional cow raising its head to check which band had been booked that year. Eventually, the procession returned to the tea-treat field and the players took their place in readiness for the official opening. The afternoon programme was filled with games and sports while the band provided background music.

Tea was a high spot and when the children had finished it was the turn of the bandsmen and no matter how hungry they were, the food just kept on coming. No committee was going to send a band home hungry and the acceptance of the engagement the following year was often based on the players’ memory of the tea.

If the weather remained fine, the evening concert was held in the field with the players still perched on those infamous forms. This was the opportunity to play music that could be described as, “a bit more substantial”.

By now, the fun and games were over and the audience was more attentive. The day was usually concluded with the traditional Serpentine Walk when everyone danced around the field behind the band, often trying to avoid the cowpats left by the field’s previous guests.

Early brass instruments (1) were extremely primitive compared to those of today. The original bugle was restricted to a few notes – sufficient for issuing battle instructions and playing fanfares. The keyed bugle, circa 1810, was a great improvement on what had gone before.

It had keys (flaps) to enable the player to play a chromatic scale, in other words to be able to play all the notes of a tune. This was to remain in use until the appearance of the cornet-a-pistons or cornopean, circa 1928, a valve instrument.

The introduction of valves was the Holy Grail that many instrument designers had been seeking. With them, instruments no longer changed pitch by emitting air at intervals along their length: they were sealed from mouthpiece to bell-end with variations in pitch achieved by using valves to divert the flow of air along differing lengths of tubing.

In the early 1840s, Adolphe Sax (2) developed a set of saxhorns which revolutionised instrument production and laid the foundation of the modern brass band. So impressed was British musician John Destin(3), that he purchased a set and he and his family played them as they toured Cornwall and elsewhere.

The new instruments made an immediate impact and Sax-horn bands began to be formed in Cornwall soon after. Whether or not they were all-brass bands we do not know but even as we turned the corner into the 20th century, some “brass bands” still had woodwind players. In some areas, however, particularly in the north of England and in Wales, woodwind players faded from the line-ups as early as the 1830s and the distinctive sound of the all-brass band emerged.

Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838 seems to have led to the formation of a number of Cornish bands and the famous St Dennis Band originated around this time. We know that St Agnes Band took part in a parade in 1837 and that Camborne Band was formed in 1841. Some bands began as volunteer military units.

These were set up in the mid-1800s when the threat of invasion was very real. Most corps had their own reed and brass band or brass band which entered into community life and took part in Cornish contests. From the 1870s Salvation Army bands ran parallel to the main brass band movement. They were and are an important and influential aspect with many fine players and composers coming from its ranks.

The Cornish diaspora took many players abroad as they travelled thousands of miles to seek work in mines across the world. Arthur Cecil Todd in his book, “Cornish Miner in America” wrote: “Their preference for the instruments of the brass and silver band grew naturally out of their own industrial landscape: the tuba, cornet, trumpet and drum were more in tune with the heavy beat of the stamps that crushed the ore and the din of the drinking saloon than the violin, cello and harp; and the hand that wielded the pick and sharpened the drills was perhaps insensitive to the string”.

The early reed and brass bands had no rules governing instrumentation and this was still the case as the all-brass units came into being. Bands consisted of an unstated number of players using whatever instruments were available on which they could play a chromatic scale.

Contesting was to change this as standardisation became an essential element when comparing performances. Music too, influenced the structure as standard sets began to be produced for a set number of players. Eventually, both the number and types of instrumentation became accepted as the norm.

Most of the Cornish bands consisted of players who could fairly be described as amateurs but well into the 1900s we hear of players being compensated for their loss of earnings when engagements were undertaken on work days. Whether or not that jeopardised their amateur status we do not know but these days, far from being paid, players are much more likely to contribute to the huge costs of running a band.

The temperance movement, advocating total abstinence from alcohol, had a considerable influence on the population and many bands altered their title to indicate that they had become a part of this movement. St Dennis Temperance Band was one of them but there were many others.

It must have been a way of increasing bookings from certain organisations but it seems that some members found it difficult to adhere to their promise to refrain from drinking alcohol and most bands had removed this aspect of their name by the 1930s.

Across the years, mothers have talked proudly of their children who played in the band. It is no different today and, apart from the obvious contribution of providing entertainment, brass bands do a tremendous service in occupying young people and providing them with an activity which they will appreciate for their entire life.

They may cease to play at some stage but they will retain their memories of being a part of a band and their love of music will never leave them. It is a pastime that costs the individual very little but rewards them with much and to quote the late Cornish composer, Goff Richards(4), “I just wonder if these days we undervalue the part that banding plays in our towns and villages.”

The Cornwall Youth Brass Band (CYBB) was founded in 1955 and held its first residential course five years later, at Pentewan, under the baton of Dr Dennis Wright. The members were, and still are, drawn from bands across Cornwall and these young people have the unique opportunity of taking part in two courses each year and of playing under some of the top names in the movement.

Early brass bands comprised almost exclusively of men. The wife of notable musician E J Williams played for St Ives Band in the 1920s but she was the exception. It was overwhelmingly a male pursuit and “no place for a woman” as one St Agnes player put it in the late 1940s. His embargo was unsuccessful, however, and since then the welcome mat has been well and truly out for ladies who now make up a sizeable proportion of players and often take the major roles.

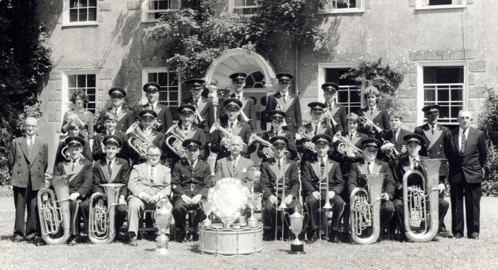

The years between the 1850s and the 1950s have been referred to as the Golden Age of Brass Bands. Cornwall then had hundreds of bands and it was not unusual for huge crowds to attend a concert and thousands to travel great distances to hear their band compete against others on the contest stage.

The 1950s marked a period of great change. The advances in broadcasting meant that top-class performances could be beamed into the comfort of our living rooms making it unnecessary to venture out on cold winter nights to listen to home-grown musicians, sometimes of variable proficiency. Local variety concerts, choir concerts and brass band concerts suddenly became less popular and the income from such events dropped dramatically.

Players too, were affected by this mind-set and with so many alternative attractions, and worsening financial situations, bands began to fold. As a consequence, there are fewer bands now but the movement is truly in great shape with many of the younger generation keen to become a part of it.

The marked technical improvements in instrument manufacture and the significant rise in playing ability means that the bands of today are of much better quality and, on that basis, we could more correctly be said to be currently experiencing the Golden Age of Banding.

A huge amount of research has and is being done to identify and record the histories of Cornwall’s hundreds of brass bands. The late John Brush was an avid researcher who devoted a huge amount of time to this. His efforts can be viewed at Kresen Kernow and, progressively, on www.ibew.co.uk. These will soon be augmented by my own collection but, despite our extensive efforts, I am sure that there are other brass bands just waiting to be discovered.

Since the early days, the brass band movement has matured. It has shaken off the cloth cap image and is now more readily accepted by the music world. This has been helped by the involvement of leading orchestral musicians like Sir Malcolm Arnold and Cornishman George Lloyd who fell in love with its euphonic sound.

With so many other casual attractions it’s gratifying that so many people are willing to devote so much time and effort to maintain this great movement – long may they continue to do so. Hobbies can be all consuming but brass banding is more than a hobby, more than something to be picked up or discarded at will: it is a way of life.

The adage “Once a bandsman, always a bandsman” is so true. It doesn’t mean he or she will always play an instrument or be actively involved but that the sound of a brass band will inspire and excite. My interest in music is wide but the sound of a brass band has a special magic: it is evocative, a part of my Cornish heritage, and conjures up memories of all those years when I was a Cornish bandsman.

Notes

(1) Brass instruments produce sound by sympathetic vibration of air in a tubular resonator in sympathy with the vibration of the player’s lips. Brass instruments are also called labrosones, literally meaning “lip-vibrated instruments”.

(2) Antoine-Joseph “Adolphe” Sax (1814 – 1894) was a Belgian inventor and musician who invented the saxophone in the early 1840s (patented in 1846). He played the flute and clarinet. He also invented the saxotromba, saxhorn and saxtuba.

(3) The Distin family was a family of British Musicians in the 19th century who performed on saxhorns and were influential in the evolution of brass instruments in then popular music. Henri Distin, son of John Distin eventually became a celebrated brass instrument manufacturer in England and the United States.

(4) Goff Richards (c. 1944 – 25 June 2011), sometimes credited as Godfrey Richards, was a prominent brass band arranger and composer. He was born in Cornwall, studying at the Royal College of Music and Reading University. Between 1976 and 1989, he lectured in arranging and at Salford College of Technology. He was the musical director of the Chetham’s Big Band for many years. In 1976, he was made a Bard of the Cornish Gorsedd. He received a Doctorate from Salford University in 1990, after a career that had seen him lead the University Jazz Orchestra to the BBC Big Band of the Year title in 1989.

Music Kernow will continue in next month’s issue. You can find out more about the next article and its release date by following Cornish Story on Twitter and Facebook. You can also find last months introductory article here.

3 thoughts on “Music Kernow – Just Brass”

Comments are closed.