Continuing the Music Kernow series, Kiera Smitheram examines the influence of Cornish music and culture and reveals how it has moulded her thinking and her life.

Music in Cornwall is an integral part of that which helps to make the county unique. From brass to choral music to dances, the Cornish musical landscape is as diverse and rich as the county itself. However, fewer and fewer members of the community are aware of the heritage that music holds and how it shapes the Duchy.1 Old hymns and popular tunes, once taught in primary schools, were sung alongside traditional English hymns and performed with the same reverence. Nowadays, the few things that the majority of young Cornish people know of music are fragmented, passed down from older relatives and exhibits and articles. It was the songs and stories of my childhood that shaped the way I approach music today. It is disheartening that so many people are unaware of the impact that music had on Cornish culture and society.

However, this is no new phenomenon. The relevance of Cornish Music has throughout history ebbed and flowed with various social, cultural, and religious reforms. Some of these influences left as quickly as they came, but some have withstood the test of time.

Such diversity developed Cornish music. As with musicians from all across the world, writers had to adapt music to suit the social climate of their own vicinities, in the case of Cornwall the bedrock is distinctly ‘Kerwenek’2 which has lasted beyond the Early Modern Era.3 This ‘feeling’ is the way in which music was performed, and it is currently being kept alive through the many diverse festivals that are held across Cornwall every year.

Cornish musical roots can be traced back to the traditions of Breton music. Many Cornish tradesmen visited Brittany because it was easier to get to by sea than to travel to places like London. Even by modern standards one can get to Brittany in approximately six hours (if conditions are fair), travelling to London from West Cornwall rarely takes less than six hours.

The melodies the tradesmen consequently gathered were very rarely written down, but passed down through generations, this aural tradition can still be heard today. Typically, the music was played on percussive instruments; early wind instruments and a string instrument either a lute or a violin for special occasions. The melodies were kept simple for people to sing and dance along to, and were easily played by musicians of all backgrounds.

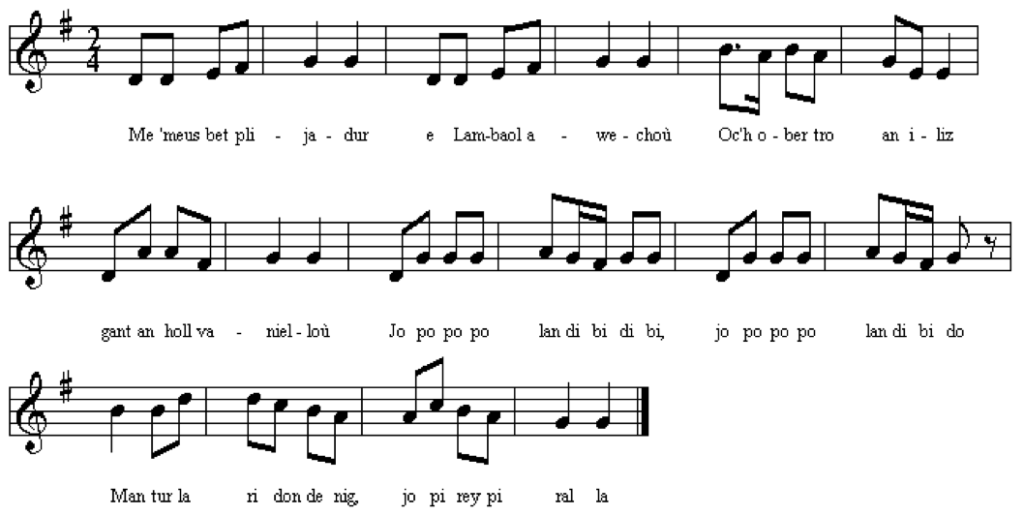

The melody of this particular piece comprises simple stepwise movements within the range of an octave. These tunes can still be heard in many Cornish songs used today, but developed for contemporary audiences as is exemplified in the sheet above.4 After the English Civil War ended in 1651 and Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell took over, the Cornish music tradition was overtaken by popular English sacred songs. Cornwall had been a strong supporter of King Charles I and his generosity towards the Duchy had been strong, so his demise was a particularly harsh blow to Cornwall.

Cromwell’s Puritanism restricted the freedom and energy of Cornish secular music at the time, due to the county’s Pagan heritage5 For example, the famous Cornish legend of the Nine Maidens condemns the act of dancing on a Sunday. First documented by Richard Carew in 1605,6 the tale recounts how nine young women and a young man missed church to go and dance on the green. As punishment they were each turned to stone. The nine stones are situated in a field alongside the A39 between St Columb Major and Wadebridge.

Though Cromwell’s influence gave rise to new legends, many of the folk festivals and practices were lost to the ages, and are still in the process of being re-introduced. It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth century that popular folk tunes were reintroduced, although some of these songs were kept in use in smaller areas before this time. The eighteenth and nineteen centuries were key turning points for Cornish music due to the surge in mining and engineering during the Industrial Revolution. Song was used to raise the spirits of the men and boys down in the claustrophobic mines and in the dangerous factories. In fact, the famous Camborne Hill song is based on the invention of the steam powered engine by Richard Trevithick that allowed carts to be transported without the need for heavy horses. The song, written in 1810 commemorates the first outing of the vehicle on Christmas Eve 1801.7

“Going up Camborne Hill, coming down,

the horses stood still, the wheels went around,”

This song was also one of the many sung by Rick Rescorla, a Cornish security specialist and former soldier who is credited with saving the lives of more than 2,000 people during the September 11th Twin Towers terror attack. He sung the songs, encouraging others to join in to increase morale among the frightened victims. This demonstrates the power these songs had over people, and why revellers still sing them to this day.

These new ‘popular’ songs helped revive music, unique to not only Cornwall, but the separate districts, with each having songs exclusive to them. They are almost vaudevillian in their nature, with many written about first loves, comedic mishaps, and local jokes. This new-found prosperity was something to be celebrated, and so local communities began to celebrate their new heroes with festivals. The towns of Camborne and Redruth celebrate in March with Trevithick and Murdoch days respectively. However, some of the older festivals had died out long before, and there were only a few ancient accounts of what had come before. With the new-found wealth, members of the Old Cornwall Society began to revive these festivals (or Kevewi).

In Penzance, the Golowan (or Midsummer) Festival was revived in 1929. This week-long festival is filled with all kinds of music, much of it performed by local schools, choirs, and performers. Percussion is a big part of the sound-scape for the Mazey Day8 as well as many other celebrations throughout Cornwall. The rush and drive of the instruments reflects the beating heart of the ocean that surrounds the peninsula. In later years, Samba music was introduced to the proceedings, and quickly spread to other festivals.

One of the wonderful things about Cornish festival music is that it is rarely melancholic. I remember at my primary school in the winter, we would hold a lantern procession around the school field and down into the town. The music was played by the cluster of instrumentalists we had, and an extra fifteen people playing percussion. It was usually raining, but our parents and locals would appear in droves just to experience this singular event.

One of my first experiences with traditional music was during a May festival in the old market town of Helston, called ‘Flora Day’.9 My godmother and her family were performing in a few of the dances which rotated throughout the day. We were able to enjoy the day given my parents had kindly taken me and my sister to the event to lend our support. Despite the greyness of the sky above, on the day I remember being surrounded by so many colours and wondrous sounds, including the town band playing the ‘Flora Dance’, a stately march in which couples dance through the streets. There are also performers recreating tales from Helston and Cornwall’s history. Cornwall’s own heritage is balanced with elements of national folklore such as the tales of Robin Hood.

The music at this festival was, and is, an integral part of the proceedings, with a bass drum striking the first beat of the dance at 7.00am. This continues until sunset, so the day is filled with song. The sense of unity through song is unlike anything I have ever heard before. It wasn’t uniform like singing in a choir, but there was a unification of spirit and drive. Not only was I hearing the lyrics or hearing the sharp calls of the brass, but feeling the passion and seeing the people of my community come together for a common cause.

As the initial procession moved down the main street, the town band began to play songs for the crowd to join in with. People of all ages were singing along, and some were dancing alongside the parade. Even the young children were able to pick up the words to the choruses with ease, as there was only one vocal line. This lack of complexity, I feel, reflects a mutual dependence and stability that is vital to not only Cornish music, but to a Cornish way of thinking. No one part of the music presides over another, making it a true meaning of “onan hag ol” (“one and all”, the Cornish motto).10

Much of this music is not performed for a profit and is available at community events, which makes it both easy and difficult for young musicians to engage with. The lack of profit also adds wholesomeness to the music, given the musicians are playing for the sheer joy of doing it, which is something that the younger generation are losing. Music has become more of an industry in today’s society with fame and royalties dictating what music is performed, whereas music in local festivals is there to evoke feeling regardless of who is playing.

Such experiences as at Helston shaped me as a musician as I now connect with music in a multi-neural way. Music to me is not just something to listen to in the background. It is something one must interact with fully in order to feel the full effects. It also taught me to appreciate a culture in which music did not always put saffron buns on the table, but brought joy to people by just existing.

A good demonstration of some of the battles that Cornish musicians have to overcome during festivals is perfectly immortalised in Malcolm Arnold’s ‘The Padstow Lifeboat (op.94)’.11 As many, if not all of the celebrations are held outside, people are willing to battle pretty much anything to ensure that the show does go on. This is depicted in a comical fashion during the first section of the piece, in which a cheerful brass band march is continuously interrupted by the blaring horn of the lifeboat. A violent and sudden storm is then heard, but soon passes and the band plays on. The piece is played all over the world, and yet it retains its Cornish sensibility and humour.

But like most things, Cornish festivals have had to move with the times. One of the biggest festivals Cornwall has to offer is the annual ‘Boardmasters’festival in Newquay. This modern music festival takes over the town for a week and is filled not only with popular modern music and big names, but also allows up and coming talents to showcase themselves to an international audience whilst being surrounded by the stunning views that, in some small way, influenced them as songwriters.

Though modern technology has found its way into festivals, there is still a beautiful timelessness about them and the music has captured this. People from all walks of life are free to come together and celebrate what it is to be Cornish, with a unique soundscape that encapsulates the wonder, beauty, and joy of the county.

Join us next month for more in the Music Kernow series. You can find the first article in the series here. You can also follow Cornish Story on Twitter and Facebook.

If you are interested in Cornish music, dance and art, you can find more relevant articles here, including the remainder of the Music Kernow series.

- Duchy: A colloquial name for Cornwall, originating from its status as a Duchy (a land ruled over by a Duke or Duchess). Cornwall shares this status in the UK with Lancaster. Each future Duke of Cornwall is the eldest surviving son of the Monarch and heir to the throne. http://duchyofcornwall.org/about-the-duchy/ (retrieved 24/02/18)

- Kerwenek: From the old Cornish language meaning “Cornish language/speech style”. http://www.cornishdictionary.org.uk/browsefield_word_value=Kernewek (retrieved 21/02/18)

- Early Modern Era: http://public.oed.com/aspects-of-english/english-in-time/early-modern-english-an-overview/ (retrieved 23/02/2018)

- Transcribed sheet music for a traditional Breton dance, Bannielou Lambaol. The similarities between the Breton and Cornish languages can clearly be seen. http://per.kentel.pagesperso-orange.fr/bannielou1.htm (retrieved 12/2/18)

- Cornwall Forever: The Civil War (online source) https://www.cornwallforever.co.uk/history/civil-war (retrieved 06/02/18)

- Richard Carew’s Survey of Cornwall (1605)

- https://mudcat.org//thread.cfm?threadid=4167&messages=9#22316 (retrived12/02/18)

- https://www.cornwalls.co.uk/events/golowan.htm (retrieved 19/02/18)

- Flora Day; http://www.helstonfloraday.org.uk/ (retrieved 23/02/2018)

- The Midday dance https://www.youtube.com/watchv=xIa6ZzNPmLQ&t=113s (retrieved 03/03/18)

- The Bob Cole Conservatory of Music at California State University, Long Beach presents: The Wind Symphony, John Alan Carnahan – conductor (Thursday, April 28th, 2016) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ncy1XS0Sctg(retrieved 20/02/18)