In the fourth article in our Cornish music series, John Roberts regales us with the history of the banjo. You can find last month’s offering which focuses on the Goonhavern Banjo Band here.

“The twang’s the thang”…or so it was according to Duane Eddy in 1959, referring to the sound of his electric guitar of course, but it was around that time, as a schoolboy in Truro, that I discovered a rather different kind of “twang”. In those days, door-to-door salesmen would come to the house flogging anything from clothes pegs to paraffin. One that my mother bought from occasionally was Arnold Hodge, a local butcher. Mum must have told him that I was into music because one day he brought me a beaten up old banjo to try and that was it, I was hooked: here was a new kind of twang that would stay with me for life.

But, apart from my obsession, what on earth has the banjo got to do with Cornwall?

Well, you’d be surprised. There was the Goonhavern Banjo Band of course, chronicled in an earlier Cornish Story by Tony Mansell, and no doubt inspired by American banjo bands such as the Yale University Banjo Club pictured above c. 1894.

There’s also the fact that the tone rings fitted to many up-market banjos (and which very much influence their sound) are often constructed of so called ‘bell bronze,’ typically 80% copper and 20% tin, some originating from Cornish mines in the past. Cornwall can also proudly lay claim to at least two world class banjo makers, past and present, based in the county.

The first Cornish banjo builder to make a real impact in the field was the legendary Alf Parker who in the previous century was producing very high quality professional grade banjos well into the 1980s from his workshop in Penzance. His instruments have often been described as works of art in their own right and nowadays used examples in good condition, if and when they come on to the market, are very highly prized by players and collectors alike.

A more recent arrival on the scene is The Cornish Banjo Company. Launched in 2014 by master luthier Louis Bauress and prominent banjo player John Dowling, the company has quickly been gaining a strong reputation throughout the banjo world. John Dowling has been playing the banjo since the age of 13 and at the age of 21 he became the first person from outside the United States to win the prestigious Walnut Valley Banjo Contest held in Winfield, Kansas: the largest known banjo competition in America.

To trace the origins of the banjo fully, however, we will need to go back much further.

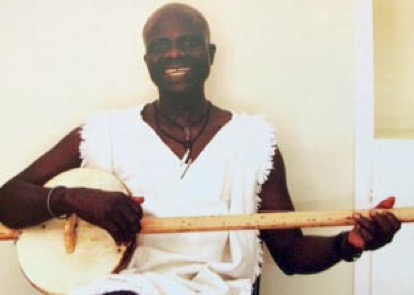

Banjo historians tend usually to hark back to the influence of early African stringed instruments such as the akonting, made from a hollowed-out gourd, a few horsehair strings and a shaped stick. Primitive instruments such as these are thought to have made their way from Africa to America via the slave trade and then over a period of some years, and through a natural process of development, to have evolved into what we now know as the modern banjo in its various forms.

Ok, but aren’t all banjos the same really? Yes, to many people they must look much of a muchness – consisting of a round bit covered in skin with a stick attached to it – but in fact there are a surprising number of instruments that go by the name of banjo. There really are many more different kinds of banjo than you might imagine.

George Formby’s ukulele banjos for example had four strings and a 6” hoop. The tenor banjos of traditional jazz and Irish folk music also have four strings but usually with an 11” hoop. The banjos featured in Bluegrass music have five strings, with a wooden resonator to increase the volume produced, whereas old time banjoists generally favour open backed five-string instruments, either fretless or fretted. The renowned folksinger and banjoist Pete Seeger even designed a special long necked instrument which enabled him to play more easily in lower keys and this became a popular choice for many players in the 1960s.

For at least ninety years the 6-string guitar banjo has been favoured by guitar players needing to double on banjo to play other kinds of music. The late 19th and early 20th centuries in England saw a vogue for seven string instruments and on both sides of the Atlantic there was quite a following for eight string mandolin banjos. Also, no banjo history would be complete without a mention of the two giants of the genre: the baritone and the bass banjo, with hoop sizes ranging from 14” to a massive 24”. And to bring the story right up-to-date: there are many small companies in various parts of the world producing, after much original R&D, wonderful modified reincarnations of the classic banjo designs of the past, in many cases equalling or surpassing the sound quality of the older models.

At the same time the electric banjo, often sporting some pretty way out body shapes, has started to make inroads into the traditional instrument market. What next, a banjo-synthesizer? (I shouldn’t joke about it: there may be one out there somewhere, for all that I know.)

Each of these banjo types has its own individual character. One is often tuned differently from the other – in the case of the 5-string banjo various tunings can even be used on the same instrument – and very distinct playing styles are required for each of them:- frailing, drop thumb, finger style, plectrum playing etc., according to the type of banjo and the musical style. When all is said and done, though, they all produce that same characteristic twang!

If there was one man more responsible than any other for bringing the banjo to the attention of the wider world in the 19th century then it was the great banjo player and fiddler, Joe Sweeney. Born in Appomattox County, Virginia, around 1810, “…as a child Sweeney wanted to express his soul in music in some sort of fashion and as he had no instrument he made one. The two Sweeney house cats – one black and the other white – were victims to this urge for expression. They mysteriously departed from this earth and only when the hide of the black cat appeared stretched over an old gourd frame, ornamented with hairs from the tail and mane of the old family grey mare did the gruesome truth come out.” (Quoted in Banjo, An Illustrated History, © 2016 Elephant Book Company)

Having eventually graduated to a rather more sophisticated and feline friendly instrument, Sweeney was soon playing at dances and house parties in the local area and by the end of 1836 he had made the transition from local, amateur musician to professional, regional performer and at that time he turned to theatrical and circus work.

In 1839 Sweeney first performed – as a blackface minstrel in those days of course – in New York City and it was not long before he came with Sand’s American Circus to the United Kingdom, where he stayed for three years. Other American banjoists were taking their music to Australia at that time and this may well have started a widespread love affair with the banjo which would last for many years, certainly well into the 1970s if the success of the Goonhavern Banjo Band was anything to go by.

During the growing banjo craze, the instrument itself was being developed and refined by the various rival manufacturers of the period, their products often being distributed by giant mail order companies such as Sears Roebuck and Ward Montgomery.

By the end of the 19th century there were some 220 banjo makers in business with, perhaps surprisingly, about two thirds of them based in the UK, mainly in London. Perhaps this is not so surprising after all when we consider that at that time the population of London was said to be twice that of New York City and four times that of Chicago, so that market forces may have been rather different in those days.

The big manufacturing names in the USA were then Vega and Gibson, and in the UK Abbott and Clifford Essex. The principal motivation of the makers at this time was to increase the loudness of their banjos in order to make them more easily heard above other instruments in a big band. They approached this challenge partly by increasing hoop size but, at a considerably more effective level, by installing the newly available metal strings and tone rings on their new instruments. The irony of this situation is that pretty soon the electric guitar (invented as early as 1931) would come along to oust the now obsolete banjo from the popularity and loudness stakes.

Earl Scruggs is now widely regarded as having been the father of the Bluegrass style of banjo playing. The three-finger technique that he developed early on is still known by his name: ‘Scruggs Style’. His band, The Foggy Mountain Boys, became pretty much a household name in the 1960s after one of their tunes, ‘The Ballad of Jed Clampett,’ was used as the theme for the long running TV series ‘The Beverly Hillbillies’. The Soggy Bottom Boys band featured in the 2000 Coen Brothers film ‘Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?’ may well have been intended as a good humoured tribute to The Foggy Mountain Boys.

So, how does the banjo fit into today’s musical scene? Well, it depends where you are coming from. In most Western pop music guitarists rule the roost whereas banjo players, in the UK at least, have long tended to be the butt of other musicians’ jokes. However, in the traditional folk scene and in the increasingly popular realm of Bluegrass music, all the various instruments seem to be able to enjoy pretty equal status – fiddle, banjo, mandolin, guitar, dobro, upright bass – they all play their special part in the band, and each one steps up to the microphone to take a solo when the time comes: isn’t this the way forward for all of us?

Actually, there is some evidence that the good old banjo may again be acquiring some semblance of a presence in Tin Pan Alley. Mumford & Sons often feature it in their music, Taylor Swift plays a guitar banjo and Dolly Parton is an accomplished five-string player.

The new breed of virtuoso professional players on the world stage include Leon Hunt in England and Bela Fleck in America. Among celebrity banjo enthusiasts in both countries are comedians Steve Martin, Billy Connolly and Frank Skinner, and the latter has reputedly been taking banjo lessons from John Dowling of Redruth. Apparently, US hipsters have also embraced the instrument in a big way. Interestingly, the other day a younger member of my family plied me with a burst of some sampled banjo playing on the recent techno hit ‘Just Dance’ by Cotton Eyed Joe. There may be hope for us all yet!

So, has the banjo finally come of age in the world of contemporary music? Absolutely, although those unkind banjo jokes still persist in the public imagination:

“How many strings does a banjo have?” “Five too many.”

“How do you make a banjo player slow down?” “Put some sheet music in front of him.”

And finally, that definition of a gentleman often attributed to Mark Twain: “A gentleman is someone who knows how to play the banjo but doesn’t.”

Glossary

Tone ring: a hardwood or metal ring that sits on top of the hoop and over which the skin or plastic head is stretched

Hoop: the round drum part of the instrument

Resonator: a wood or metal cover attached to the back of the hoop

Ukulele banjo: a small banjo fitted with a four-string ukulele neck

Mandolin banjo: similar but fitted with an eight-string mandolin neck

Frailing: a style in which the player strikes the strings with the back of the nail(s) in a downward movement, catching the fifth string with the thumb on the way up again for the next stroke

Drop thumb: like frailing, but here the thumb drops down to pick out additional notes; also known as clawhammer style

Finger style: where the thumb plucks downwards and the fingers upwards, as in classical guitar playing

Plectrum playing: a small flat tool (plectrum) is used to pluck or strum the strings

Blackface: theatrical makeup used by white performers to represent black persons, as in the BBC TV’s Black & White Minstrel Show, 1958-78

Fretted/fretless: frets are thin metal bars set into the banjo neck at right angles to help produce accurate notes; fret-less banjos are used by traditional players for a period sliding effect

Music Kernow will continue in next month’s issue with Philip Hunt’s offering on the prominent Cornish brass band composer and arranger – Goff Richards. Follow Cornish Story on Twitter and Facebook to find out more. You can also find the first article in the series here.

This is a great article. I’ve been a Cornwall-based banjo obsessive for nearly four decades and I learned quite a bit here. Respect! And thanks.

At ( 83 ) an accomplished plectrum banjo player.

Over the years I have acquired several instruments, plectrum, tenor, 5 string banjos etc etc. All in perfect playing condition., I live in the Stockport Area of South Manchester, Sadly the time has come for me to find good homes for my lovely instruments, players, rather than dealers.

Interested persons please get in touch on my email address below or on my land line 0161-312-5799 .