Lady Justice (Photo: Pixabay)

Considering the length of bookshop shelves on crime and punishment it seems that many of us have an insatiable appetite for the genre. Television, too, brings us a seemingly endless stream of programmes and while watching one recently, a documentary titled You Be the Judge: Crime & Punishment, (6th May 2025) I concluded that few people are happy with the level of sentencing in Britain. In it, groups of judges, police officers, ‘old lags,’ crime affected families and other groups all expressed their concern that the sentences handed down are too lenient. A sad comment on a country which prides itself in its justice system.

Thoughts of W S Gilbert’s words in The Mikado spring to mind:

His object all sublime

He will achieve in time

To let the punishment fit the crime

The punishment fit the crime

Was it ever thus I wondered?

Back in the Anglo-Saxon era, retribution seems to have depended on your status or your ability to compensate your victim. Even murder could be remitted by the forfeiture of money or land so it was a system which suited the well-off but certainly not the ordinary man In the street – or in the lane!

Jump forward to 1215 and the Magna Carta and it was still the case. The document was written by the barons but it did little to help the common man – the vast majority of the population at that time. The hierarchy must have taken comfort from its protection but it did little to help when succeeding rulers exercised their whims and prejudices through the Royal Prerogative. The Star Chamber of the Tudors and Stuarts was superior to Common Law and was often used with impunity as a political tool.

The blindfold on ‘Lady Justice’ signifies impartiality: the dispensing of justice without regard to wealth, power or other status: a standard to which every society should aspire. We now live in times when we can add mercy to those ideals, but it is hard to ignore those who suggest that it has gone too far when a sentence can be mitigated with an apology or by admitting guilt. The half-sentence remission for good behaviour also feels like a slap in the face to the victim or their family.

Few would argue that the death sentence should still be handed down for setting fire to a cornrick or for stealing a sheep but there are those who opine that the punishments are no longer proportionate, that in many cases, the penalties are neither sufficient punishment nor are they a deterrent.

Our prisons were once termed ‘Houses of Correction’ which suggests a desire for a system of rehabilitation that goes hand in hand with punishment. This, I’m sure, has proved to be effective in many cases but our daily news programmes continue to be filled with reports of shootings and stabbings.

Cornwall, of course, is not immune to these problems but a look at the local scene was my motivation in putting pen to paper and having climbed from my proverbial soapbox, I’ll restrict myself to crimes and punishments within our borders.

The following cases are not comprehensive – they are examples – but behind each one is a story of intrigue and misery worthy of being developed into an article. Many involved the ultimate penalty and it will be seen that it was not reserved for murder and there may be some surprise at the range of crimes for which society used this remedy.

Crime in Cornwall

Theft

Surely theft is the most common crime and it is not difficult to take the view that justice in the early cases was administered with little thought of mercy: with little consideration whether the crime was committed out of greed or need.

The Second Royal Charter for Truro (in 1175) was probably received with great relief. It was directed “To the Barons of Cornwall – all men – both Cornish and English,” And among the list of privileges was the permission to hang its thieves.

The rope was useful and expedient to remove undesirables from the community and I guess that it also served as a warning to others not to tread that path but whether it was reserved for recidivists, rather than first offenders, is not always clear. With a touch of mercy in mind however, the value of items stolen was sometimes understated to avoid the miscreant receiving the ultimate penalty.

For the more trivial offences there were a range of punishments and an edict in Truro during the 1770s stated that those convicted of theft, even a loaf of bread, were to be stripped naked from the middle upwards, tied to a cart driven around Middle Row, and “whipt until their bodies were bloody.”

For many though, it was the rope and the following shows that many people in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century were executed for what we would now consider to be trivial offences. The law had to be upheld and many thieves paid the ultimate price for their criminal act.

Philip Randall, aged 21, was executed at Bodmin in 1785 for burglary.

John Richards, aged 25, was executed at Bodmin in 1785 for robbery with violence.

Thomas Roberts, aged 34, and Francis Couth, aged 45, were executed at Bodmin in 1786 for stealing sheep.

James Elliott, aged 23, was executed at Bodmin in 1787 for burglary of the Mail.

William Congdon, aged 22, was executed at Bodmin in 1787 for stealing a watch.

Michael Taylor, aged 22, was executed at Bodmin in 1791 for stealing a mare.

James Dash, aged 23, was executed at Bodmin in 1791 for burglary.

James Symons, aged 25, was executed at Bodmin in 1791 for stealing an ox.

James Frederick, aged 33, was executed at Bodmin in 1795 for robbery.

Joseph Williams, aged 28, was executed at Bodmin in 1795 for stealing sheep.

William Howarth, aged 24, was executed at Bodmin in 1798 for housebreaking.

William Roskilly, aged 34, was executed at Bodmin in 1801 for housebreaking.

John Vanstone and William Lee, both aged 37, were executed at Bodmin in 1802 for robbery.

John Williamson, of unknown age, and James Joyce, aged 27, were executed at Bodmin in 1805 for shop-breaking.

The West Briton of the 18th October 1811 reported on a case held at the Session at Launceston when Jonathan Barnes was found guilty of stealing oats. He was sentenced to be publicly whipped.

The West Briton of the 20th August 1813 reported on a case at the recent Cornwall Assizes. John Budge was convicted of taking the mark of white thread out of a quantity of cordage belonging to his Majesty, and was sentenced to be transported for fourteen years. (A white strand was incorporated in the King’s cordage to distinguish it from all other, and this mark, Budge was found removing from fifty-foot lengths of rope in his ropewalk at Torpoint. Second-hand King’s cordage was sold only in six-foot lengths.)

William Rowe, aged 51, was executed at Bodmin in 1818 for stealing sheep.

Michael Stephens, aged 27, was executed at Bodmin in 1820 for stealing sheep.

The West Briton of the 25th January 1822 reported of the case of five boys: James Holman, Henry Warren, James Lean, Richard Cock, and James Prideaux who were found guilty of stealing a bag of comfits (sweets) from Samuel Lean’s standing at Camborne Fair, in 1822, They were imprisoned for one month and privately whipped.

The West Briton of the 17th August 1827 reported on a case involving Henry Randell who was indicted for breaking into a Landrake house in 1827. He stole two cotton shirts and the Chief Justice said that the case came under Mr Peel’s Act of the 1st July 1826 by which breaking into a house and stealing to any amount, is a capital offence. Breaking a window and taking things out of the house with a stick, through the window, clearly came under the meaning of this Statute. He was found guilty and given a death sentence.

James Eddy, aged 29, was executed at Bodmin in 1827 for Highway Robbery.

Thomas Coombe, aged 21, was executed at Bodmin in 1828 for housebreaking.

The following cases from Cornwall Quarter Sessions I appeared in the West Briton of the 23rd April 1830:

James Olmud was found guilty of stealing a pair of worsted stockings, belonging to Thomas Bryant, which had been left to dry on a hedge. He put them on and left his by the hedge. When taken into custody he fell on his knees and begged for mercy. He was imprisoned for twelve months with hard labour. Jane Tinner was found guilty of stealing a sheet, several articles of bedding and clothing belonging to William Rowe, near Madron Churchtown. The items had been placed there to dry. She was imprisoned for three months with hard labour.

The following cases from Cornwall Quarter Sessions II appeared in the West Briton of the 23rd April 1830:

John James was sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing a watch. Samuel Harris was sentenced to three months hard labour and whipped for stealing a hen from James White. William Robins was sentenced to fourteen years transportation for robbing his mistress, Elizabeth Goodman. William Sim was sentenced to fourteen years transportation for robbing his master, Walter Cock, of Falmouth,

The following case from Cornwall Quarter Sessions III appeared in the West Briton of the 23rd April 1830:

Issacher Binney, a boy aged 15 years, was convicted, chiefly on the evidence of his companion, John Sims, aged 11, of stealing two pounds of candles, belonging to Stephen Michell, a miner, in the changing house of Poldice Mine. Binney, a repeat offender, was sentenced to be transported overseas for fourteen years, not to be served in the prison hulks at Plymouth.

The following case from Cornwall Quarter Sessions II appeared in the West Briton of the 28th October 1831:

James and Philip Thomas were convicted of entering John Luke’s brewery and stealing beer. James Thomas was sentenced to transportation for seven years and Philip Thomas to twelve months’ imprisonment and hard labour at the tread-mill at Penzance.

The following case from the Cornwall Assizes appeared in the West Briton of the 11th May 1832:

Charles Penrose, Benjamin Bright, and Henry Millet were sentenced to death for burglary but were transferred from Bodmin prison to the Devonport Captivity hulk to undergo the mitigated punishment of transportation for life.

The death penalty for most cases of theft was abolished in 1832 but other punishments and deterrents remained available to the justice system.

Charles Mansell, aged 19, a single man, a carter of Kenwyn, Truro, was imprisoned in Bodmin Gaol in 1833 for stealing a paper parcel containing a Naval Uniform Coat and Waistcoat and other articles, the property of John Tozer.

In what seems trivial offences, Richard Trudgion of Truro was flogged in public for stealing goods worth sixpence from Thomas Daniel (the flogging post was adjacent to St Mary’s Church, Truro – the site of the eventual Cathedral), thirteen-year-old John Trebell of Pydar Street, Truro, was sent to the House of Correction for seven days and privately whipped for stealing potatoes, and two young boys were given a ‘good thrashing’ by their parents in the presence of the sergeant of police for stealing sweets.

The following case from the Cornwall Easter Assizes appeared in the West Briton of the 17th April 1835:

Samuel Symons, Henry Symons, and Thomas Kendall were transported for life for stealing two bullocks, belonging to Mr William Blake of St Minver, Charles Mansell 1 (the more observant may have noticed that this young man appears three times in the list of crimes and, yes, he is my ancestor) was transported for seven years for stealing hay belonging to Mr Joseph Carne, of Truro and James Deeble and Matthew Dawson were imprisoned for one month with hard labour and whipped at the mine for stealing candles at the Consolidated Mines.

At the final Launceston Assizes, in 1838, the last case was that of a boy, aged 13, who had stolen three gallons of potatoes. Lord Denham sentenced him to penal servitude. (Old Cornwall Societies – Autumn 1962)

During the 1850s the sentence of ‘being transported,’ was still being handed down and James Coombs was heading for 14 years in Australia, courtesy of her Majesty, for stealing a shirt, John Flinn received seven years for stealing a silk handkerchief (possibly a serial offender) and James Lampshire ten years for stealing a black mare.

The West Briton of the 9th January 1868 reported that four boys: Henry Guest, Henry Bailey, William Trelease and J Downing were charged with breaking into Carne’s Brewery, and stealing a quantity of beer. The magistrates sentenced Guest and Bailey to 12 lashes each, Trelease, nine lashes and Downing six lashes. Guest and Bailey were also charged with stealing a silver chain from Mr Winterhalder of Market Street for which Guest was sentenced to Bodmin Gaol for one month, and Bailey a fortnight, both with hard labour and both to be privately whipped a day before they left the prison. The sentences of flogging were duly carried out by Constable Prater in the presence of the mayor, a magistrate and the superintendent of police.

The West Briton of the 11th April 1878 reported that Joseph Trewartha, a miner, was convicted at the Cornwall Assizes for assaulting John Taylor and stealing his watch, near Redruth. He was sentenced to ten months’ imprisonment and 25 lashes of the ‘cat’ which he received in the corridor, within the hearing of most of the other prisoners. His cries and groans were said to “serve as a terror to him and others for a long time to come.”

Prostitution – ‘the world’s oldest profession’

Prostitution on our streets was once rife and numerically high on the list of cases to be dealt with by the magistrates. For some men, it was a reason for visiting a public house and in the book, Edwardian Truro by June Palmer there is a case “of a young girl engaged in prostitution throughout one evening in the back yard of the Red Lion in Calenick Street.”

Prostitutes, variously termed ‘Ladies of the Night,’ ‘Nymphs of the Pavement,’ whores and a number of other less delicate epithets, plied their trade wherever there was a likelihood of ‘business’.

The Golden Lion in Calenick Street, Truro, was typical of the ale houses offering this ‘service’ and one Truronian was happy to share his memories. “When entering the Golden Lion’s front door there was a wooden serving hatch to the left. Through this the landlord sold his beer and spirits. A corridor ran the full length of the building and to the right were several numbered doors, each one opening into a room furnished with tables and chairs, a chaise longue and an open fireplace … The rooms within the pub, and what took place in them, held no secrets. Those who frequented the establishment were clearly aware of their purpose and that of the prostitutes who gathered there to ply their trade.”

It seems to have been an ‘open-secret’ and we are left to wonder if the authorities acquiesced to the activity providing the peace was not disturbed!

The West Briton of the 30th March 1849 reported that Grace Stephens was sentenced to six months hard labour for keeping a common bawdy and disorderly house with four prostitutes. Responding to complaints by “respectable inhabitants of Calenick Street,” the police confirmed the presence of “five or six men and four prostitutes there at a time.”

The West Briton in February 1856 reported that Mary Sholl was fined for knowingly permitting persons of bad character to assemble in her house in Truro. The constable found the house in a disorderly state, full of militiamen, sailors and prostitutes.

The West Briton in October 1857 reported on an unusual case. James Francis, the landlord of the Black Boy public house in River Street, Truro, was prosecuted in that he “did knowingly permit and suffer divers persons of notoriously bad character to assemble and meet together in his house.” The case was dismissed, however, because there was no proof that the women (prostitutes) in question had been seated there and that he had had ‘harboured’ them.

The Western Morning News of the 28th November 1893 reported on a case involving Mr Carveth who was fined £5 with costs and loss of licence for harbouring prostitutes and allowing his house to be used as a brothel.

No doubt many young women chose prostitution as a means of survival but gradually it was driven underground by societal attitudes and the Street Offences Act of 1959 which made it an offence “for a common prostitute to loiter or solicit in a street or public place for the purpose of prostitution.”

That it still exists is undeniable but polite society can close its eyes and pretend that it has no place in modern life.

Traffic Offences

Another aspect which occupied the magistrates’ time, and no doubt their patience, was the behaviour of the carriers as they delivered goods and people around the increasingly populated urban areas and country lanes.

The West Briton in November 1844 makes interesting reading as it reported that no less than sixteen van drivers were summoned by a government agent, named Stowell, for speeding through the streets of Truro. They had all been driving faster than four miles an hour which was the speed allowed by law for carriages of that description.

The West Briton of the 1st November 1844 reported on a number of traffic offences. Henry Mansell (another ancestor of mine) and William Clemow were each charged with three offences and fined £20, Matthew Bennett with two offences against his name was fined the same amount whilst Joseph Pascoe, Wm Pearce, and Samuel Lake, were each fined £10 and W Sowden, T James, J James, W Fidock, J Lean, J Weeks, W B Kellow, T Allen, and W Sparks, were each fined £5. All the parties had to pay the expenses. They were allowed fourteen days to pay the penalty and costs, and if not paid, a writ was to be issued. If there were no goods to meet the distress, the parties were to be committed: in the £20 cases, for three months’ imprisonment, and in the other cases, for one month. The purge was not restricted to Truro and at Penzance, on the following day, a large number of van owners were summoned before the magistrates, and were all, with one exception, fined £5. At Camborne, too, several van owners were brought before the Bench and fined £5 each.

These measures were no doubt introduced with pedestrian safety in mind and in 1909, in Truro, a ten miles-per-hour speed limit was in place and in an attempt to enforce it, the police purchased bicycles to apprehend speeding motorists.

Wife Selling

Now, here’s an odd one, and one which clearly caused a great deal of offence in respectable circles. Thomas Hardy in his 1886 novel, The Mayor of Casterbridge, details one such case, albeit fictional, but there are many instances where it actually took place either because a husband wished to be rid of his wife or, with her connivance, saw it as an alternative and cheaper gateway to a divorce.

The West Briton 13th November 1818 reported an incident at Bodmin Market where a man named Walter, of Lanivet, led his wife by a halter tied around her waist and offered her for sale. A man by the name of Sobey bid sixpence and was declared to have bought her. They left to shouts of the crowd and to the satisfaction of the husband.

A similar case involved William Hodge who led his wife, Rebecca, by a straw halter into the Redruth market crying: “A woman for sale.” William Andrew bid two shillings and sixpence and that turned out to be the highest bid. That was not the end of it however, and at the Truro Quarter Sessions in April of the following year, William Andrew was fined and sent to prison for three months. Later, Hodge was also convicted and received three months’ hard labour for “selling his wife by auction.” The Royal Cornwall Gazette expressed surprise at the leniency of the sentence and described the affair as “an offence so disgusting that we hope that it will never be repeated in the county.” Francis Edward has written an article about the case. 2

The West Briton of the 27th March 1835 reported that people attending St Austell market were surprised when George Trethewey of St Stephen-in-Brannell entered with a woman with a halter tied round her waist. He had tired of his young wife and wished to sell her to the highest bidder. Various bids were received and she was eventually sold for four-pence less one penny market toll (the sum usually charged for the sale of a pig).

At Callington open market in 1846, a man offered his wife for sale and received the sum of two shillings and sixpence (equivalent to about £20 in 2025). The West Briton of the 16th January 1846 stated that neither the authorities nor members of the public intervened in what it reported was, “so disgraceful a scene.”

The West Briton of the 5th August 1853 referred to a couple who appeared before the superintendent Registrar at Bodmin to be married. He suspected, however, that one of them was already married and advised them that if that was the case then they were liable to be transported. The man protested and produced a certificate from the woman’s husband stating that he had purchased her. Despite that, the Registrar refused to marry them and they left very disappointed.

Sundry Crimes

Crimes, of course, are many and varied and before we move onto those which involved the loss of life, we have a section which includes a wide range of misdemeanours – some serious, others less so, and that is reflected in the penalties handed down to the perpetrators.

They include begging, vagrancy, bastardy cases, absconded apprentices, forgery, trespass, being drunk and disorderly, and a whole range of what now may be considered petty offences. These often resulted in a fine or a spell in the local lock-up but there was always the Bodmin Bridewell 3. There, they served their sentence and were often whipped either during or at the conclusion of their time there.

Some offences were more serious and even if no loss of life was involved, they may well have been included in the long list of crimes for which the ultimate penalty was handed down.

From the Old Cornwall Societies’ Journal we have the sad case of Anne Upcott, the Quaker daughter of the Vicar of St Austell. She was tried at Lostwithiel for the heinous crime of mending her clothing on a Sunday for which she was fined five shillings and placed in the stocks where she was publicly mocked. Happily, a stranger took pity on her and arranged her release.

William MoyIe, of unknown age, was executed at Bodmin in 1791 for killing a mare.

Richard Andrew of unknown age was executed at Bodmin in 1802 for forgery.

Pierre Francois La Roche, aged 24, was executed at Bodmin in 1812 for forgery.

The West Briton of the 20th August 1813 reported that William Wallis had been executed for killing a sheep belonging to Mr Thomas Pethick.

Elizabeth Osbourne, aged 20, was executed at Bodmin in 1813 for setting fire to her former employer’s corn stack.

The West Briton in 1814 reported that Truro millers were accused of mixing two hundred tons of China clay with their flour over a two-year period. It caused illness in the neighbourhood, amongst the soldiers and sailors, and the French prisoners of war on Dartmoor. In 1816, the chief offender was sent to prison for two years and his accomplices fined. They were also burnt in effigy in the streets of Truro. Francis Edward has written an article about the case. 4

The West Briton of the 7th April 1815 reported that William Carbis, his son, also William Carbis, and Francis Bassett, his son-in-law, were indicted for stealing two ewes at Madron. The animal had been divided and parts of it were found at their houses. They were tried at Cornwall Assizes but being sea-faring men, they had gone to sea immediately the evidence was discovered. They were tried in absentia but the Judge proceeded to pass a sentence of death on them.

The West Briton of the 11th September 1820 reported that Jane and Mary Ann Waters, sisters, were sent to Bodmin gaol for assaulting the master of Kenwyn Poorhouse where they had been sent as paupers. They had refused to have their hair cut short and, in resisting, they had assaulted the master and a female attendant and threatened the life of the mistress. Eventually, their hair was cut and they were transferred to the House of Correction as the only place in which they could be safely trusted.

Jane Hooper, aged 39, was given six months hard labour in 1823 for having six bastard children of which three were chargeable to the parish.

William Oxford, aged 21, was executed at Bodmin in 1825 for setting fire to a corn stack.

John, William and George Best were fined one shilling in 1825 for assaulting Thomas Horrell.

Rebecca Johns of Truro was sent to the House of Correction in Bodmin in 1825 for assaulting Elizabeth Vigurs.

Stephen George was committed to the Bridewell in 1825 for a lack of sureties for a breach of the peace against James Phillips.

Christina Hope, aged 31, was sentenced to six months hard labour in 1827 for masquerading as a fortune-teller.

Charles Mansell, aged 17, single / labourer / of Kenwyn, Truro, fined 20 shillings in 1831 for trespass.

William Hocking, aged 57, was executed at Bodmin in 1834 for bestiality.

The West Briton of the 17th April 1835 reported the indictment of five men: Richard Mitchell, Joseph Lean senior, Joseph Lean junior, Henry Dyer, and William Rawlyn, for involvement in a riot at Camborne. One man had resisted arrest and had struck the constable, injuring him. The other men tried to prevent the constables from putting him in the lock-up which was described as being six-feet long, five- feet wide and six-feet high. The cell was broken into and the prisoner released. The evidence was conflicting and the Jury acquitted all the men.

The West Briton of the 20th March 1840 reported on the use of the town stocks: “Yesterday, a shoemaker, named Thomas Huddy, well known in Truro for his drunken habits, was placed in the new stocks under the Coinage Hall, for six hours, for non-payment of a fine for drunkenness. The punishment proved very attractive; the hall being surrounded the greater part of the day by a large number of spectators who appeared much amused by the spectacle.”

The West Briton of the 4th October 1844 was clearly unhappy at the following spectacle: “On Monday last, a very disgusting scene was witnessed in Truro, which we hope, for the credit of that town, will not be repeated. Two women, old and notorious offenders as drunkards, were placed in the stocks, under a sentence for six hours, we believe, in the middle of Boscawen Street, opposite the market gates.” It seems that one was quite laid back about situation and simply continued to knit and took no account of the hundreds of people and children who gathered there. The other woman was very distressed and wept continually.

The West Briton of the 24th October 1845 reported a number of cases dealt with by the Magistrates:

Edwin Lloyd was found guilty of begging in the streets of Truro and was committed to the House of Correction for one month, Philippa Johns received one month in prison for disorderly conduct, Frances Letcher was committed for trial at the next sessions charged with keeping a house of ill-fame, John Nankivell was fined 20 shillings with costs for emptying a nuisance in the daytime, Charles Bartlett, from Staffordshire was committed for fourteen days for begging, Samuel Harris and Henry Polkinghorne were each fined five shillings for drunkenness and William Daw, a serial offender, was found guilty of being drunk and disorderly. He was ordered to find two sureties in £10 each, and himself in £20, to be of good behaviour for the next twelve months, and in default of these sureties he was to be committed for six months with hard labour.

The West Briton of the 22nd September 1848 referred to a most disgraceful scene in the principal street in Truro whereby a young woman named Murton, was seized and placed in the stocks. Some 12 months previously she had been fined for being drunk and disorderly but had left the town to avoid paying. The newspaper referred to it as, “A most brutal and indecent punishment … but more especially so in that of a woman.” The girl had been placed outside the Town Hall to undergo the punishment, when some gentlemen paid the fine and obtained her release.

The West Briton of the 9th May 1862 reported that Nathaniel Cole was placed in the stocks for six hours at Camelford for not paying a fine of five shillings and five shillings costs, for being drunk and riotous. In a similar case, Bawden, of St Erth, was placed in the stocks in Foundry square, Hayle, for being drunk and not paying the fine.

The Stocks are feet restraining devices used as a form of punishment and humiliation for minor crimes. They were still widely used in Cornwall in the 1860s but seemingly only for being drunk and riotous. The usual punishment period was six hours and the last recorded use in Cornwall was alleged to have been in Camborne in 1866.

Murder

Now we come to the ultimate crime for which there was once, only one remedy – the rope.

Robert Brown, aged 33, was executed at Bodmin in 1785 for the murder of a boy.

William Hill, aged 25, was executed at Bodmin in 1785 for murder.

Ben Willoughby, aged 20 and John Taylor, aged 26, were executed at Bodmin in 1791 for murder.

William Trewarvas, aged 23, was executed at Bodmin in 1783 for murder.

G A Safehorne, aged 35, was executed at Bodmin in 1796 for murder.

Joseph Strick, aged 25, was executed at Bodmin in 1804 for murder.

The West Briton of the 8th May 1812 reported on the public execution of William Wyatt which seems to have been a botched job. He had been convicted of murder and was led to the gallows where he could hardly stand. He was supported but fell sideways and the rope slipped on his neck. The knot came nearly under his chin leaving the windpipe, more or less, free of pressure. It was said his attempts to breathe was distinctly heard for 20 minutes by the surrounding spectators. The newspaper report stated: “This shocking scene was occasioned by the executioner not letting the drop fall suddenly, by which means the rope, which was stronger than ordinary, as Wyatt was a large-sized man, and which had not been greased to make the knot slip readily, got in the position above described. After hanging the usual time, the body was delivered to the surgeons, who were waiting in the prison, by whom two incisions across the breast were made, and then delivered to Wyatt’s friends by whom it was immediately interred.”

The headline in the West Briton of the 8th May 1812 was: “Two More For The Gallows.” An old woman and her daughter were committed to Bodmin Gaol accused of the murder of the daughter’s bastard child. The Coroner’s inquest had returned a verdict of wilful murder against them. It seems that the child was a week old when it was strangled and placed under a stone: the mark of the cord round its neck was still quite fresh.

William Burn, aged 21, was executed at Bodmin in 1814 for murder.

John Simms, aged 30, was executed at Bodmin in 1815 for murder.

Sarah Polgrean, aged 37, was executed at Bodmin in 1820 for killing her husband with rat poison.

John Barnicoat, aged 24, John Thompson, aged 17, and Nicholas Gard, aged 42, were executed at Bodmin in 1821 for murder.

Elizabeth Commins, aged 22, was executed at Bodmin in 1828 for the murder of her child by beating its head against its crib.

John Henwood, aged 29, was executed at Bodmin in 1835 for parricide.

William Lightfoot, aged 36, and his brother, James, aged 23, were executed at Bodmin in 1840 for the murder of Mr Norway. In his book, Funding the Ladder, Dean Evans wrote that John Passmore Edwards travelled from Truro to Bodmin to witness the public execution. More than 20,000 people attended, with special trains that stood alongside the gaol so that the passengers could view the hanging from their carriage. Edwards walked the 20 miles home to give himself a chance to consider what he had just witnessed and was to campaign against capital punishment for the rest of his life.

Matthew Weeks, aged 23, was executed in front of a crowd of several thousand people outside Bodmin Jail in 1844. He was convicted of murdering his girlfriend, Charlotte Dymond. Like many others, I attended a mock court session in Bodmin when members of the public were given the opportunity to ‘decide’ if he was guilty or not. The overwhelming opinion of our group was that the evidence was too flimsy to convict him.

Benjamin Ellison, aged 61, was executed in 1845 at Bodmin for murder.

James Holman, aged 29, was executed at Bodmin in 1854 for killing his pregnant wife by hitting her with an iron and pushing her head into an open fire.

William Nevin, aged 44, was executed at Bodmin in 1856 for murder.

Selina Wadge, aged 29, was executed at Bodmin in 1878 for the murder of her youngest child but, by then, hanging was carried out in private – public hangings had been consigned to history.

William Bartlett, aged 46, was executed at Bodmin in 1882 for the murder of his illegitimate two-week-old baby daughter.

Valeri Giovanni, aged 31, was executed at Bodmin in 1901 for the wilful murder of Victor Bayliff, a seaman native to Jersey. He was the first person to be executed in the new hanging pit.

William Hampton, aged 24, was executed in 1909 at Bodmin for the murder of his 17-year-old girlfriend by strangulation. He was the last man to be hanged in Cornwall.

Russell Pascoe, aged 23, and Dennis Whitty, aged 22, were executed in 1963 for the murder of 64-year-old William Garfield Rowe of Constantine.

Punishment

Lock-ups existed in various towns around Cornwall and were, no doubt, well used. They were for minor offences and holding cells for those who were to be transferred to prison.

The Truro Lock-up, complete with its set of stocks, once stood at the end of Middle Row (now Boscawen Street), facing the Coinage Hall/Stannary Court. In the 1770s it moved to a site at the rear of the Pydar Street Almhouses (now demolished) and the West Briton report of the 16th September 1825 refers to the conditions there: “When a person is charged with an offence and the magistrate thinks it proper to commit him, he is transferred to Bodmin; then if the next Quarter Sessions be held at Truro, he is conveyed with a motley group of various characters, well secured, to be deposited in the small lock-up place called Truro town-gaol. Having recently visited this prison I can describe it. It contains two small rooms upstairs, and a strong room below, strewed with straw, with a block in the centre, to which the refractory are chained. As there is no privy, and the rooms have no ventilators, the air was found exceedingly close and offensive. … these places being intended only as lock-up houses or cages, there can be no doubt that they all must be very unfit for the reception (even temporary) of a number of persons, unconvicted, several of whom may and are often found ‘not guilty’ of the offence charged to them.”

The type of punishment and the degree of severity depended very much on the type of crime. It ranged from humiliation or fines, prison sentences, right through to transportation and execution.

Cornwall’s prison at Launceston was truly dreadful. Launceston Prison, or Lanson Jail if you prefer, was in a thirteenth century Motte & Bailey castle, a location also used for executions.

Conditions there were clearly appalling and the old Cornish saying ‘Like Lanson jail’ is still used to describe a place that is in a disorderly state. Memory of the place lies behind the nickname ‘Castle Terrible,’ described by the Cornish antiquarian Richard Carew in the early 17th century.

In its time it provided incarceration for some well-known people including the Catholic martyr Cuthbert Mayne, the quaker George Fox and the Civil War General, Richard Grenville.

In 1776 it was referred to as ‘the County Gaol at Launceston for Felons’. There were many complaints about the appalling conditions there and its remoteness from the area it served. From Bodmin it was a long journey across the Moor, a formidable experience during the winter months.

Launceston Gaol continued to operate until 1829, even after a replacement was built in Bodmin.

In 1777, John Howard, a prison reformer, published The State of the Prisons in England and Wales, in which he referred to deplorable prison conditions. The book detailed overcrowded prisons, unsanitary conditions, and lack of separation by gender or crime type, along with other abuses. Howard’s work sparked significant interest in prison reform and helped pave the way for improvements.

The Government clearly listened to the representations being made and a new prison was built in Bodmin – on Berrycombe Road.

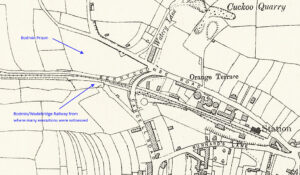

1888-1915 Map showing location of Prison

1888-1915 Map showing location of Prison

The new gaol opened in 1779 with accommodation for 100 prisoners in individual cells with blankets and straw bedding, hospital rooms, a chapel, and running water with a heating apparatus. There were also condemned cells for those awaiting execution.

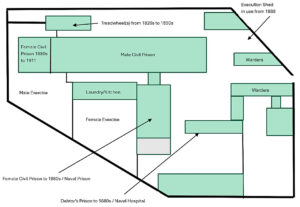

Within about 50 years the number incarcerated there was well in excess of that figure, no doubt exacerbated by the closure of Launceston Prison and the provisions of the Gaol Act of 1823 5 which required separate facilities for the many classes of prisoners.

The new complex included a debtors’ prison, previously located in Crockwell Street, and a Bridewell for petty criminals, defined as those who committed crimes which were of a minor or less serious nature. A rather vague definition but it would have included vagrancy, shoplifting, minor theft, runaway apprentices, trespassing and suchlike. They are often characterized by the theft of low-value items or offences that don’t cause significant harm and there are a few examples in the foregoing pages. The Bridewell was not a ‘soft touch’ as the sentences served there often included hard work and physical punishment such as whipping.

Convicts of all classes were subject to strict discipline and ‘hard labour’ with a range of punishments including solitary confinement, being placed in irons, flogging and the notorious treadwheel, a particularly harsh penalty as it involved treading the wheel for four hours at a time.

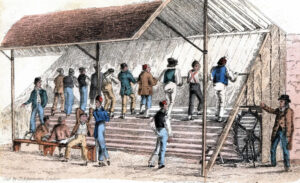

A Treadwheel (not at Bodmin)

A Treadwheel (not at Bodmin)

Sir William Cubitt was an English engineer who was concerned with the employment of criminals and in 1818 he invented the treadmill for use as punishment and the grinding of corn. Elsewhere, and possibly at Bodmin, the corn contributed to the gaol’s financial accounts.

The apparatus comprised wooden steps mounted on a cylindrical drum, initially long enough to accommodate 10 convicts but later models could take up to 30. As it rotated, the men in total silence, were forced to move up to the next step and so the cylinder continued to turn. Its use was discontinued by the Prisons Act of 1898. 6

Bodmin’s first treadwheel was installed in the early 1820s and remained in use until the end of the century. It seems, from one of the cases listed, that there was also one in Penzance in 1831.

The treadwheel’s purpose was to subject the convicts to physical punishment designed to break their will: it was in fact, an instrument of torture. I have mentioned that my relation, Charles Mansell, was in Bodmin Gaol during the 1830s so it is possible that he was subjected to this treatment.

In 1827 there was a rebellion against its use and the West Briton of the 18th May reported that prisoners sentenced to hard labour, had refused to step onto the treadwheel. Two magistrates had remonstrated with them but they still refused and began to break parts of the machine and act aggressively towards those in authority. The Cornwall Militia was deployed and the rioters attacked them and tried to grab their muskets. Several convicts were knocked to the ground by the butt end of the soldiers’ weapons and as they lay injured, the others withdrew. Five of the most aggressive were dragged away and locked in separate cells and James Sowden, the ring-leader, was ordered to ascend the wheel. Again, he refused. He was secured and flogged following which the other rioters, fearing the same punishment, took to the wheel.

Prisoners had to work, and oakum picking, breaking stone, sawing wood and other work around the prison such as in the laundry or the kitchen for which there was a payment which in the case of debtors, probably helped pay off what they owed.

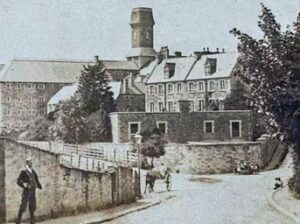

Despite the construction of new buildings, the prison was declared ‘Unfit for Purpose’ and it was agreed that it should be replaced. By the late 1850s, building was underway. The new four-storey, 220-cell prison opened in February 1860 on the same site but not on the same footprint, thus enabling the facility to continue operating while construction work was in progress.

The 1860s Prison (Photo: unknown source – credit will be added if advised)

The 1860s Prison (Photo: unknown source – credit will be added if advised)

As with the first prison, many executions took place there and many on-remand or convicted prisoners were held in very harsh conditions. This West Briton report of the 19th October 1866 referred to the type of food provided: “The prison diet included only bread, potatoes and a very thin gruel but it was suspected that many less well-fed than the inmates deliberately stole in order to enter gaol for the winter months.”

The West Briton of the 19th of October 1866 stated: “All men over the age of sixteen, sentenced to hard labour, worked on the treadwheel or treadmill to grind corn for the prison. Those under that age, and females, were at this date given the alternative tasks.”

By the 1860s, the original treadwheel/treadmill had been in place for over 40 years and the West Briton of the 19th October 1866 included a statement from the Governor about its replacement: “Since the date of my last report some considerable progress has been made in the preparations for the new tread wheel and corn mill, sanctioned by your honourable Court, to meet the requirements of the Prison Act of 1865, 7 as regards the carrying out of sentences of hard labour in the county prison. Until the above work is fully completed, it is impossible to carry out the provisions of the Act as regards first and second-class hard labour as strictly as I could wish. The dietary is still unchanged, awaiting the written sanction of the Secretary of State, which has been delayed, pending the revision of the prison rules. As this is a very necessary part of prison discipline, it is to be hoped that this sanction will soon be given, to enable me to carry out in its integrity this part of the system.”

Diagrammatic Plan of the 1860s Bodmin Gaol site

Diagrammatic Plan of the 1860s Bodmin Gaol site

The Prison Inspector’s report for the year ending 31st March 1887 appeared in the West Briton of the 8th December of that year: “… hard labour of the first class has been carried out by means of the tread-wheel. The naval prisoners, although using the wheel at the same time as the others, are kept quite apart and out of sight by means of a screen. The other labour consisted of weaving, mat-making, and oakum and fibre picking. The conduct of the officers had been good. The conduct of the prisoners had also been good, and there had been no corporal punishments. Sixteen prisoners had been transferred from Plymouth and Exeter to assist in the building of the new naval prison. Owing to the small number of female prisoners, laundry work had at times to be performed by the males.”

This then was Cornwall’s civil prison from 1779 to 1916. It continued to be used by the Navy for a few more years after that before being sold and allowed to fall into disrepair.

A visit to Bodmin Gaol is now a very enjoyable experience and one which I can recommend but my first visit was prior to its renovation and conversion to a hotel, and I remember well what an austere experience it was. We walked the corridors and visited the cells which were ‘furnished’ as they were when they were occupied by less casual visitors. Nowhere did the phrase, “abandon hope all ye who enter here” seem more appropriate.

Transportation

The Transportation to penal colonies half-way around the world was regarded with dread and in many cases, it involved a ‘one-way ticket’. It was used as an alternative to capital punishment, where a capital sentence had been commuted and for habitual petty criminals.

From 1654 until the outbreak of the American War of Independence in 1776, British convicts sentenced to transportation were shipped to the British penal colonies in America. This punishment increased after the Transportation Act 1717 and it is estimated that 80% of these, about 42,000, were sent to Maryland and Virginia on the east coast of America.

The American War of Independence meant that the penal colonies there could no longer be used so a new location was needed and from the 1780s to the 1850s about 164,000 convicts were transported to the hot and hostile environment of Australia. The authorities established two major convict colonies – Botany Bay in New South Wales (1788-1840) and Van Diemen’s Land (1803-1853) which were later joined by others including Swan River in Western Australia.

The First Fleet, which arrived in Australia in 1788, was the first major transportation fleet to the Australian colonies. It consisted of eleven ships that carried approximately 1,400 convicts, soldiers, and free settlers. The journey from England to Australia took around eight months, and the fleet landed at Botany Bay before later establishing a settlement at Sydney Cove.

The journey itself was fraught with danger and many convicts died during the long sea voyage. Others didn’t survive their sentence (seven-year, fourteen-year or life) due to the harsh conditions or the treatment meted out.

The television historical drama Banished painted a vivid picture of the harsh conditions and the treatment of those ‘lucky’ enough to have their sentence commuted. That compelling account of life in an Australian penal colony, was based in Botany Bay but I recently published a true account of my ancestor, Charles Mansell, one of ‘Her Majesty’s Seven-Year Passengers,’ who served his sentence in the dreaded Van Diemen’s Land. Despite his criminal record, Charles later joined the police force and the Tasmanian Library stated that it was not unusual for emancipated convicts to join the police and there are a number of newspaper reports in the 1850s which refer to him being a police officer in Hobart. The Tasmania State Library and Archives Service advised me that a pardon was necessary to return legally to Britain. Most convicts were given only conditional pardons which gave them freedom of movement in the Southern Colonies (including New Zealand) but did not allow them to return home. Those leaving Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) had to produce evidence of their status.

The Death Penalty or Capital Punishment

Across the years the ultimate penalty was administered with a high degree of cruelty and the aim of making the miscreant suffer as much as possible was clearly intended as a deterrent to others. I do not intend to describe the various methods used except to say that the much-detailed penalty of being ‘Hung, Drawn and Quartered’ was used for treason or where the case could be construed as such. Cornishmen Michael Joseph (An Gof) and Thomas Flamank suffered this fate for their part in the 1497 Rebellion.

The Waltham Black Act in 1723 8 established a system known as the ‘Bloody Code’. This imposed the death penalty for over two hundred offences and many examples can be found in the lists above.

In Cornwall, many early executions were carried out at Launceston and at Bodmin Common, at the edge of the town. From the early 1800s they took place outside the walls of Bodmin Gaol in full view of members of the public. Early hangings involved the ‘short drop’ 9 which did not break the vertebrae in the neck immediately, leaving the condemned to die a slow, often painful death by strangulation. Public executions, like public whippings, were intended to be a deterrent to others but there is no doubt that many of the people who attended, enjoyed such occasions. The hangings were reported in grisly detail in the press and they doubtless made good reading for those unable to enjoy the morbid pleasures of such a spectacle at first hand. The executions were huge public occasions and people travelled great distances to witness them. One popular vantage point in Bodmin was from a carriage on the Bodmin to Wadebridge Railway, just to the south of the prison wall.

Robert Peel’s Gaol Act of 1823 10 brought many changes to prison life as it focused on penal reform rather than harsh punishments. It marked the beginnings of government efforts to impose general standards in prisons across the whole country and reduced the number of crimes punishable by death by 100, including the removal of many minor crimes.

On the 7th April 1854 the West Briton reported the execution of James Holman who had murdered his wife.

“The Public Hanging at Bodmin drew a huge crowd with many travelling from west Cornwall – from the locality where the murder took place. A large number had travelled to Truro by the West Cornwall Railway and on the roads to Bodmin there were open waggons, carts, and vans, crowded with passengers. Others made their way by foot and all were heading to, the ‘place of painful excitement’.”

The West Briton of the 22nd August 1862 reported on Cornwall’s last public hanging, that of 28-year-old John Doidge of Launceston. He had been sacked and replaced by Roger Drewe for whose murder he was sentenced to be hanged by Calcraft, Cornwall’s well known and expert hangman. “About half-past eight on Monday morning, the carpenters commenced the erection, on the principal floor of the female department of the gaol, of steps and a platform inside the southern wall of the prison – the platform being on a level with the grating floor of the drop on the exterior; and at ten o’clock these preparations were completed. The drop has the same southern aspect, and is nearly over the same site as that of the old gaol; and, consequently, the fields sloping down from the northern side of the street at the western part of the town – ‘Bodmin highlands’ – afford the same facilities for view of the dread spectacle that have been available to so many thousands at previous executions. We understand that it had been intended, in the building of the new gaol, to erect the drop at the northern part; but this purpose was abandoned because of the comparatively small assemblage of the public to whom the execution of a capital sentence could be made visible.”

In 1868, public hangings were abolished with the ‘Capital Punishment Amendments’ act. Each prison had to build a pit or a shed in a private location: no longer would ‘Joe Public’ be able to view the grisly spectacle.

The early 1870s saw another milestone with the introduction of the ‘long drop,’ 11 where the death was instantaneous.

Pending completion of the Execution Shed (in place by 1888) executions were carried out in the courtyard, on temporary scaffold.

In 1965, the death penalty for murder in Britain was suspended for five years and in 1969 the cessation was made permanent except for treason, the punishment for which remained in place for a further three decades.

I’ll finish on a rather curious event which was included in the West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser of the 10th October 1845 revealing the extent of Cornish superstition in curing the sick. “At the execution of Ellison, at Bodmin, in August last, it was noticed that there was a very active demand for pieces of the rope by which the poor wretch was suspended, for each of which the executioner received one shilling. Many conjectures were hazarded as to the future use of these mystical fragments, but no one was willing to reveal the secret. It happened a few days since, as one of the surgeons from the infirmary was dressing a patient who had a wound in his back, that he espied a dirty cord about his neck, from which hung, over the breast, a little chintz bag. On asking what it contained, he was told that it was, ‘some of the roop (sic) what cured his back last time’. This answer only whetted the curiosity of his surgeon to hear more, and after a little further questioning he learnt ‘that it was a bit of roop (sic) the man was ‘anged with to Badment (sic) – that t’other bit was buried, and as the roop (sic) rotted the wound healed’. Of course, a piece of stout rope required some time to rot and as there was nothing malignant about the ulcer, and rest was allowed, dame nature at length effected a cure, but the hangman’s rope ran away with the credit…”

Endnotes:

- Charles Mansell’s story can be found here: https://cornishstory.com/2024/08/03/notoriously-bad-was-he/

- https://cornishstory.com/2025/02/05/two-shillings-and-sixpence-a-cornish-wife-sale/)

- The first Bridewell opened at Bridewell Palace in 1553 – the former residence of King Henry VIII. Following that, all such facilities were referred to by that name and every county was required to build one.

- https://the-cornish-historian.com/2025/03/08/the-great-cornish-bake-off/

- The Gaols Act of 1823 stated that prisons should be made secure; gaolers should be paid; female prisoners should be kept separately from male prisoners; doctors and chaplains should visit prisons and lastly, attempts should be made to reform prisoners.

- The Prisons Act of 1898 was a significant piece of legislation in the United Kingdom that aimed to reform and improve prison conditions. It marked a move towards a more modern and humane penal system, emphasizing rehabilitation and constructive purpose in prison work.

- The Prisons Act of 1865 was a significant piece of legislation in the UK, consolidating and amending the law relating to prisons in England and Wales. It formalized the “separate system” (isolation) and introduced the “silent system” with the goal of deterring crime through harsh conditions, including hard labor, hard fare, and hard board,

- The Black Act of 1723, also known as the Waltham Black Act, was a piece of legislation that significantly expanded the scope of capital punishment in Britain. It was enacted in response to rising crime, particularly poaching, and the perceived threat of Jacobite unrest. The Act made over 200 offenses punishable by death, many of which were considered relatively minor crimes, leading to it being called the “Bloody Code”

- The short drop is a method of hanging in which the condemned prisoner stands with the noose around the neck. A trap door is then operated leaving the person dangling from the rope. Suspended by the neck, the weight of the body tightens the noose around the neck, effecting strangulation and death. Loss of consciousness is typically rapid and death ensues in a few minutes.

- The Gaols Act of 1823, also known as Peel’s Gaol Act, was a landmark piece of legislation in British history initiated by Home Secretary Robert Peel. It aimed to improve the conditions and organization of prisons across England and Wales, marking the beginning of government efforts to standardize prison practices

- The ‘long drop’ refers to a specific technique used to ensure a swift and humane execution. It involves a carefully calculated drop that breaks the prisoner’s neck, causing immediate death. This method was introduced in Britain in 1872.

References:

Bodmin Jail Internet site: https://www.bodminjail.org/discover/about-bodmin-jail/history-of-the-building/

The book: Bodmin Gaol by Alan Brunton

The book: A Guide to Bodmin Jail and its History by Bill Johnson

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bodmin_Jail

The Morbid Tourist: https://themorbidtourist.com/bodmin-jail-attraction/

The West Briton newspaper.

The Western Morning News

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history, is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and a co-editor with Cornish Story.