Tradition tells us, that a ball of apple-wood with a thick coating of silver is the object contended for. Two goals are each one mile distant from the place where the ball is thrown up, being thus two miles apart from each other. One is designated the ‘town goal’ and the other the ‘country goal’ and the aim of each party of players is to get the ball to goal.

No doubt certain aspects of the game have evolved across the years and for those interested in its history then these next few paragraphs may be of interest:

Sometime around 1584, John Nordon 1 wrote:

“The Cornish-men they are stronge, hardye and nymble, so are their exercises violent, two especially, Wrastling and Hurling, sharpe and severe activities; and in neither of these doth any Countrye exceede or equall them. The firste is violent, but the seconde is dangerous: The firste is acted in two sortes, by Holdster (as they called it) and by the Coller; the seconde likewise two ways, as Hurling to goales, and Hurling to the Countrye.”

Richard Carew in his Survey of Cornwall 1602, pages 86 to 89, provides a very detailed description of the rules as it was played and some, including that the ball is only to be passed backward, has led some to suggest that our more modern game of Rugby Union originated in Cornwall.

“Hurling take his denomination from throwing up the ball, and he of two sorts: in the east parts of Cornwall to goals, and in the West to the country.” 2

John Wesley, probably in the late 1700s, was less than enthusiastic about the game and in his diaries, he wrote a less than flattering observation that smuggling, drunkenness, cockfighting, wrestling, hurling and godless riot were the favourite amusements of the people of St Ives. We can assume from that, he would not have been a passionate supporter of the sport. Despite his views, it seems as popular as ever in certain places.

In The History of Cornwall From the Earliest Records and Traditions to the Present Time 1824, Dr Borlase observes:

“… [that hurling] is peculiar to this county, it is scarcely possible to trace the origin. It is known to be ancient; but in what age it started into existence, or from what source it took its rise, we can have nothing to guide us but the glimmerings of conjecture. It is possible that it might have originated among the ancient clans; and, in order to keep alive the local attachment of their respective vassals, it is easy to conceive that each chief would endeavour to promote an exercise so well calculated for the purpose, and serving at the same time as a criterion to measure the strength of the rival party. Hurling is a trial of skill and activity between two parties, of twenty, forty, or any indeterminate number; sometimes betwixt two or more parishes; but more usually, and indeed practised in a more friendly manner, betwixt those of the same parish; for the better understanding which distinction, it must be premised, that betwixt those of the same parish there is a natural connexion supposed, from which no one member can depart, without forfeiting all esteem.

As this unites the inhabitants of a parish, each parish looks upon itself as obliged to contend for its own fame, and oppose the pretensions and superiority of its neighbours.”

On the 28th October 1896, The Sketch, 3 a British illustrated weekly journal, included this fascinating report under a very appropriate heading.

“An Ancient Game.”

“Although ‘hurling,’ as one of the most ancient of Cornish games, was formerly played in many parts of the county of Cornwall, it has been practically kept alive for many years past exclusively by the men of St. Columb Major.

But an attempt has just been made to resuscitate the game in the neighbouring parish of St. Columb Minor, the contest having taken place on the great sandy beach at Newquay. Perhaps this example may prove contagious, and the game may again become an ‘annual’ throughout the ‘Delectable Duchy’. In the event of such a revival, it is unlikely that all the ancient conditions under which the game has always been played at St. Columb will be observed and adhered to.

Certain of its rough features do not quite accord with present-day ideas, and an appreciable revival of ‘hurling’ must almost certainly be contingent on the elimination of a certain amount of the danger and rowdyism that have been associated with the game as it has been handed down from remote times.

The St. Columb men have ever constituted a physically vigorous community. It may be said that the Charter under which their weekly market has been held for more than five centuries and a half was won on the battle-field, for it was in recognition of their bravery at Halidown Hill that King Edward, two days afterwards, at Berwick-on-Tweed, granted this Charter to their leader, Sir John Arundel. It is not difficult, therefore, to understand why the descendants of these men have seen no reason to lessen the dangers of their ancient and cherished game by even substituting in the play a ‘ball’ made of somewhat softer material than the time-honoured ‘silver’.

Hurling, as it has continued to be played at St. Columb from time immemorial, is a contest between ‘Town’ and ‘Country’ – that is to say, men residing in the town are matched against men residing in the rural parts of the parish. There is no limit as to numbers on either side, but both sides muster in as great strength as possible.

The game is played annually, on Shrove Tuesday, and is continued and brought to a close on the following Saturday week. Carew, who wrote his ‘Survey of Cornwall’ three hundred years ago, has stated that ‘Hurling taketh his denomination from throwing of the ball, and is of two sorts, in the east parts of Cornwall to goals, and in the west to the country’. It is evidently ‘hurling to the country,’ as it was understood in Carew’s time, that has always been played at St. Columb, although it involves the use of ‘goals’.

The combatants assemble at a certain spot in the centre of the town, where, after three cheers have been given and a short interval has been subsequently allowed, the ball is thrown up in the air. This ball is of apple-wood with a thick coating of silver, and weighs twelve ounces.

From the spot where the ball is thrown up, the two ‘goals’ are each a mile distant, and are thus two miles apart. One is designated the ‘Town goal’ and the other the ‘Country goal,’ and the object of each party is to get the ball to its particular goal. The side that succeeds in doing this becomes the winner, and the individual who touches the goal with the ball is entitled to keep the silver trophy in his possession until the next ‘hurling day,’ when it will be his privilege to ‘throw it up,’ and thus to commence another year’s game.

When the ball is thrown up, there begins at once a general and vigorous scramble for its possession. Should it be seized by a representative of the ‘Town’. he calls out ‘Town ball,’ and throws it to some other member of his side in the direction of the ‘Town goal’. Corresponding action with the contrary object would be taken. if the ball were seized by a member of the ‘Country’ party. If the possessor of the ball should be free from the reach of any opponent, he may run with the ball towards his goal until he is intercepted by one of the other side.

But whenever the man holding the ball is touched by an opponent, the rule of the game is that he must forthwith ‘deal’ the ball-that is, throw it from him. As the game proceeds, the players pursue the ball through and over all obstacles.

Over hills and dales, hedges and ditches, they make their way. There is a good deal of strategy displayed by the contending parties; and as each side tries to get the ball to its own goal, so the other side endeavours to prevent it. Consequently, representatives of both sides are placed in various parts of the field, with the object of assisting their colleagues or retarding their opponents, as the case may be; and a fleet-footed player, outrunning his pursuers as he makes towards his goal with the ball in his hand, often finds someone lying in ambush to intercept his advance. But most of the players keep in the vicinity of the ball; and watchers from St. Columb Church-tower note with interest the swaying of the crowd as the ball is thrown or carried first in one direction and then in another.

In the ‘Survey of Cornwall,’ to which reference has been already made, Carew says: The ball in this play may be compared to an infernal spirit, for whosoever catcheth it fareth straightways like a madman, struggling and fighting with those that go about to hold him; and no sooner is the ball gone from him but he resigneth this fury to the next receiver, and himself becometh peaceable as before. I cannot well resolve whether I should more commend this game for the manhood and exercise, or condemn it for the boisterousness and harms which it begetteth; for as on the one side it makes their bodies strong, hard, and nimble, and puts a courage into their hearts to meet an enemy in the face, so, on the other part, it is accompanied with many dangers, some of which do ever fall to the players’ share: for proof whereof, when hurling is ended, you shall see them retiring home, as from a pitched battle, with bloody pates, bones broken and out of joint, and such bruises as serve to shorten their days; yet all is good play, and never attorney nor coroner is troubled for the matter.

At the conclusion of the game the players repair once more to their trysting-place in the centre of the town, where the ball is held aloft by the man who has succeeded in touching his side’s goal with it, all joining in the three cheers with which it is thus ‘called up’.

It is conceivable that when a ‘silver ball,’ weighing three-quarters of a pound, is thrown to and fro in a crowd frenzied with the excitement of the game, considerable damage to property as well as to person is the result. Yet no one thinks of making any monetary claim for damage done on ‘hurling day’. Householders can take the precaution, if they think fit, of boarding up their windows; but if they fail to do this, they knowingly run the risk of having them smashed or other injury done to their property. So long as the play is in the streets, the cries of ‘Town ball’ and ‘Country ball’ are varied by the sounds of breaking glass and other indications of wreckage; but as this is one of the recognised concomitants of the game, it is accepted and regarded simply as an incident in a campaign. In fact, the mob holds high festival on ‘hurling day,’ and this particular phase of rowdyism has its field-day consecrated by public sanction and immemorial custom.

The condition of many of the players at the close of the day, as in Carew’s time, has always testified to the dangers involved in the use of a metal ball; for, as an old hurler of the present generation lately remarked, ‘Many people are seen walking about with their eyes in a sling’ after this annual festival has been held. It was also long the custom-though not observed now to the same extent as formerly-for ‘old scores’ to be settled on ‘hurling day,’ when the guardians of the peace did not interfere to stop a fight with fists any more than to stop the hurling itself. The scrimmage for the ball naturally afforded abundant opportunities for such collisions. Altercations which often followed the conclusion of play not unfrequently produced similar results; while the skill of the wrestler found abundant exemplification by men contending for the possession of the silver trophy. Sometimes, if legitimate opportunities did not offer, they were created. Thus: a sturdy man, wanting to distinguish himself, addressed another hurler on one occasion by saying, ‘I’m as good a man as you be, Jan Hawken’. In response to this challenge, Jan replied, ‘Then come along with me’. Collaring the aggressor, Jan dragged him along the road, and, giving him the wrestler’s ‘flying mare,’ threw him heavily on a great heap of stones. It was in this way that Jan settled the question at issue between him and his challenger and proved that the other was not ‘as good a man’ as himself. This redoubtable hurler, now in his eighty-fifth year, joined in the game that was played on Newquay beach the other day.

The origin of hurling is lost in antiquity. It is suspected, however, to have possessed some ecclesiastical connection, for the east window of the parish church was commonly a goal in former times, while tradition asserts that in at least one parish the ball was always ’thrown up’ in the church itself, and that the clergy took a leading and active part in the play. For some reason or other this ancient Cornish game has been so generally discontinued that it practically survives in only one parish, though, in this particular district, it is as hardy an ‘annual’ as it ever was. The recent attempt to revive hurling in a neighbouring parish will probably be attended with success; but it may be confidently stated that the chances of a general revival would be all the greater if the danger of physical injury were lessened by the substitution of some less murderous ball than the terrible ‘silver’ orb that custom prescribes for use. As a relic of antiquity the game is singularly interesting; as a physical exercise it is most invigorating; and these considerations might not unreasonably ensure the revival of its old-time popularity if the element of needless danger were eliminated and the risks of broken noses and fractured skulls reduced to the average minimum of popular games.”

In Cornish Lads at Play by E S Burrow – The Boy’s Own Annual 1898 – the question of how long it has been played has been posed but nobody knows.

“The proverbial ‘oldest inhabitant’ can but say that his grandfather played it, and that his great-grandfather had his head broken through it. Local historians and eminent antiquaries have sought for its origin, and have come back from the search battled and beaten, leaving it shrouded in the dim mists of bygone days.

Grand old game, fit child of dear, wild rugged, but matchless Cornwall. ‘Hip! hip! hurrah!’ for the old county, its pancakes, pilchards, and pasties, and one more for St Columb and its ‘hurling-day’.

For weeks previous to Shrove Tuesday both sides are busy practising in the lanes and fields, and for this purpose ‘lattice’ balls are used, that is wood balls cased with tin; and it is surprising how quickly the hands are accustomed to catch the ball, even when thrown with great force. The game starts at 4.30pm and throughout the afternoon the country-folk, young farmers, farm-labourers, village tailors, blacksmiths and shoemakers may be seen pouring into the town, the majority wearing white smock frocks and warlike countenances.

Every village, hamlet, and farmstead has sent its contingent. Talskiddy, Trebudannon, Trekenning, Trezaddern, Tregatillion, Tregameer, and Trevithick, to say nothing of the ‘Pols’ and the ‘Pens,’ have sent their sturdiest and fleetest.

Meanwhile in the town all is stir and bustle. Schools, workshops, and businesses are closed, shops are carefully shuttered and the windows of private houses are boarded. By four o’clock a big crowd has congregated in the square.”

Black’s Popular Series of Colour Books 4 had this to say about the game in 1925:

“They have other special games of their own too of which the chief is ‘hurling,’ though now only kept up in the parishes of St Columb Major and Minor, in other words in the neighbourhood of Newquay, though a collection is made at St Ives in a silver ‘hurlers’ ball’. The game is that of a ball being flung and thrown from one to the other, with goals which may be two miles apart. Sometimes one match takes days to decide. It is an extremely rough-and-tumble sport. In the season a match is played on the wide flat firm expanse of Newquay sands and hundreds take part in it, badges being used to discriminate between the players. And on Shrove Tuesday a game is played in the town of St Columb the ball being thrown up in the market-place and all traffic being held up for the occasion. The goals used to be ‘either the mansion-house of one of the leading gentlemen of the party, a parish church, or some other well-known place’. The ball is rather larger than a cricket-ball, but not so large as a football, and is silvered over. The struggle is expressively described by Carew: ‘The hurlers take their way over hills, dales, hedges and ditches, through bushes, briers, mires, plashes, rivers; sometimes twenty or thirty lie tugging together in the water, scrambling and scratching for the ball’. These customs and sports are only samples, for there are many quaint ideas still held in certain parishes which would almost provide the material for a book by themselves, and are far too numerous to collect together in a sketch like the present. However, enough has perhaps been said to show how the Cornish spirit still lingers in spite of the influx of ‘foreigners’ growing ever greater yearly.”

In Bygone days in Devonshire and Cornwall 1874, Mary Elizabeth Whitcombe refers to there being two methods of hurling in Cornwall at the commencement of the seventeenth century and states that the best description of the game is given by Carew who says:

“Hurling taketh his denomination from throwing of the ball, and is of two sorts; in the east parts of Cornwall to goales, and in the west to the country. For hurling to goales there are fifteen, twenty, or thirty players, more or less, chosen out on each side, who strip themselves to their slightest apparel, and then join hands in ranke one against the other…”

At St Columb Town

Shrove Tuesday is a special day in St Columb and a truly historic event and one that I have attended for over 30 years. It’s when the traditional game of Cornish Hurling takes place (not to be confused with the Irish game). A second match takes place a few days later and this pattern of events has been in place for more years than anyone can recall.

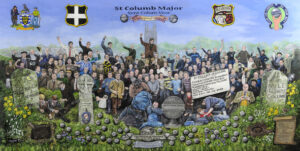

The event is so important to the folk there that St Columb Major Parish Council commissioned the well-known artist Dick Twinney to paint a historical record of their event. The result, a four feet by eight feet framed acrylic painting affixed to the wall in an alleyway adjacent to the Town Hall.

Dick Twinney’s Hurling painting (included with his permission)

Dick Twinney’s Hurling painting (included with his permission)

On arrival in the town, the occasional visitor walking up the street towards the market place end of town, near the church, will probably find it strange to see the almost deserted streets and the shuttered windows, especially if they haven’t been forewarned. But they may sense an air of excitement and anticipation which gradually increases as the crowd begins to gather near the war memorial.

There is a gathering of families, friends young and old alike, many of whom who have several generations that have been a part of what is about to unfold.

It begins with the ceremony of ‘calling up’ the ball which introduces last year’s winner: Craig Allen from a St Columb family who won both events for the Town.

Craig Allen 2024 winner of both events

Craig Allen 2024 winner of both events

The 2024 winner – for the Town

The 2024 winner – for the Town

Town Crier, Sid Bennet, reads the ceremonial script which includes last year’s outcome and alerts the crowd that something exciting is about to begin.

A young lad, in this case the son of last year’s winner, stands atop the step ladder and prepares to hurl the silver ball into the eager crowd of men. Probably a memory he will cherish for the rest of his life.

Craig Allen steadies the steps as his son prepares to throw the ball into crowd with these traditional words:

Craig Allen steadies the steps as his son prepares to throw the ball into crowd with these traditional words:

“Town and country do your best. But in this parish, I must rest”

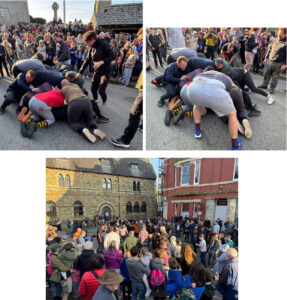

The silver ball is thrown to the crowd and the game is underway.

A scramble follows, like a messy rugby ruck, with all players vying for possession.

A scrum on the tarmac

A scrum on the tarmac

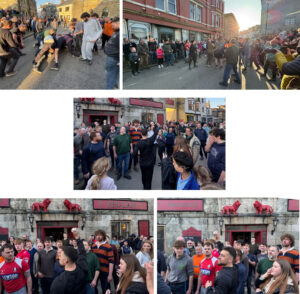

The game moves up and down the streets: a hard rough and tumble but it’s in good spirits and the camaraderie and friendly rivalry is apparent, even between the opposing players.

The game pauses outside the Red Lion where Marco Ciarleglio, 10 times winner, holds the ball aloft.

The game pauses outside the Red Lion where Marco Ciarleglio, 10 times winner, holds the ball aloft.

This is an occasion for all and in the mayhem the children are not forgotten. The ball is passed between them so that they will one day recall that they were a part of something special – a tradition which they may continue in the years to come!

The game continues with advantage held by each side – albeit often short lived. Eventually though, the ball emerges and a run is made but for how far? The chase is on and possession continues to swing from side to side but then, as the evening begins to draws in, a quick pass, a good take and a player triumphs with a run to goal. Sean Michael Johns is the 2025 winner.

Sean Michael Johns, a 12 times winner, reigns supreme and is carried shoulder high through the street

Sean Michael Johns, a 12 times winner, reigns supreme and is carried shoulder high through the street

I Have not witnessed it but I am told, “Just when you think it’s all over, the pubs begin to fill and the celebrations begin with the traditional ‘drinking the silver beer’. The ball is dipped into the winner’s drink and gallon after gallon is called up and the ‘silver beer,’ as it is known locally, is shared amongst all those present.”

Many of those who took part in the event try to get a sip of the drink, perhaps in the hope of bringing them good fortune for the hurling rematch which takes place the following weekend.

Down St Ives

Not to be outdone, St Ives too, celebrates this very Cornish event and this set of photos show that they maintain the tradition equally as enthusiastically.

The game continues on Harbour Beach

The game continues on Harbour Beach

Silverwell

Another area which is said to have once enjoyed the game of hurling is Silverwell, a hamlet which straddles the boundaries of Perranzabuloe and St Agnes. Whether it is true or not I do not know but according to Cornish historian Tony Mansell, the place where he grew up is said to have derived its name from an incident which took place at ‘some time’ in ‘some location’ when the silver hurling ball was lost in a well. With his tongue firmly in his cheek, Tony said, “I’ve found no other reason for the name so let’s just say that if tidn true then it oughta be!”

Footnotes:

- John Norden was a 16th century historian.

- The Survey of Cornwall by Richard Carew. ISBN 0-85025-389-6

- The Sketch ran for 2,989 issues between 1 February 1893 and 17 June 1959. It was published by the Illustrated London News Company and was primarily a society magazine with regular features on royalty, aristocracy and high society, as well as theatre, cinema and the arts. It had a high photographic content with many studies of society ladies and their children as well as regular layouts of point to point meetings and similar events.

- Cornwall (Black’s New Series of Colour Books) Spring. 1925 Publisher: A & C Black Ltd, London

All photographs are Barry West © unless stated otherwise.

Barry West

Barry West

I have lived in Cornwall all my life and feel very proud and privileged to have done so.

I was born in Redruth in 1961 and began my life living close to Gwennap Pit, where I was christened in this most remarkable and special place – where John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, is said to have preached on no less than 18 occasions.

When I was in my teens, I was fortunate enough to find a copy of Daphne Du Maurier’s Vanishing Cornwall – it was truly an inspiration, and it’s where I began my very own quest to uncover the stories about the people, places, architecture, art and literature and traditions and history here in Cornwall and wherever our ancestors have left their mark, often in distant lands.

I can remember reading this quote from Daphne Du Maurier’s Vanishing Cornwall. “Here was the freedom I desired, long sought-for, not yet known. Freedom to write, to walk, to wander, freedom to climb hills, to pull a boat, to be alone … I for this, and this for me.”

To me it sums up much of what many of us must also feel and think.

Over the years it has become quite evident from my research that many people have left to make a new life, often in difficult circumstances, and many people have come to Cornwall and were captivated by what they found. Their contributions have left an indelible mark that is also an important part of our story.

Over the last 40 years or so I have uncovered many lost and forgotten stories which I have been able to share through social media, the press, radio or television and through my books .

I have organised many different historical community events – one of the most memorable was the Miners’ Memorial weekend at St Newlyn East, where a slate memorial was erected and three days of community-based events to remember the 39 men and boys who lost their lives at North and East Wheal Rose – Cornwall’s worst mining disaster on the 9th July 1846

I feel great pleasure in uncovering the stories, doing the research, and sharing the outcome, so that our heritage, our culture, our history and those that have gone before us, are not forgotten. This passion is deep-rooted and the desire to find out more and share my findings is unquenchable. The more I uncover, the more driven I become.

I feel it is imperative we preserve our Cornish historical narrative to ensure that future generations can connect with their Cornish culture and heritage to gain a deeper appreciation, connection and understanding of who we are. That the important place education can play in bringing those stories to life for the benefit of those who will help keep the stories alive.

Barry West

April 2025

Good to read this comprehensive story about hurling thanks again Barry for the research