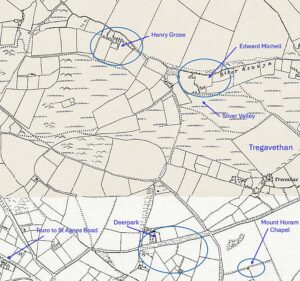

Locations derived from the 1840s Tithe map and thought to be the same in 1851. There seems to be more than one possibilities for Butt Lane.

Locations derived from the 1840s Tithe map and thought to be the same in 1851. There seems to be more than one possibilities for Butt Lane.

I was initially drawn to this case because Silverwell was my home for many years, it was where I was raised and where I spent so many years playing in the woods and the lanes and working on a farm during the long summer holidays.

Many fruitless hours have been spent trying to trace the locations mentioned on maps and other documents but they remained stubbornly hidden until a reference to Mount Oram (Horam) Chapel led to the conclusion that the action took place in Tregavethan – some distance from Silverwell. Helpful contributions from others (see acknowledgements) gradually began to narrow the area of interest and a study of the Tithe Maps finally enabled the locations to be established.

Why it should have been attributed to Silverwell in Court Documents and newspaper reports is not clear but perhaps, back then, that village was considered to have stretched (perhaps unofficially) beyond its present boundaries. The discovery of an area in Tregavethan known as Silver Valley also added to the intrigue and posed the question that that may have been the cause of the confusion.

Despite it not being in My Village, I found the case interesting and well worth pursuing.

William and Mary Kendall rented a tenement called Deerpark, in the parish of Kenwyn, a small farm about five miles from Truro – a few fields to the north of Penstraze on the Truro to St Agnes road. On the 19th of April 1851, the tranquillity of this small and scattered community was disturbed … Old Mr Kendall had suffered a violent death but was it accidental or murder?

William was aged around 70 and Mary was 51: they had been married for four years. William was known locally as Old Mr Kendall and it was suggested that he was not on the best of terms with all his neighbours.

Up until the previous January, Elijah Teague, Mary’s youngest son by a previous marriage, had been living with them. In some reports he is described as William Kendall’s son in law but in more modern times he would be termed his stepson. On the 1851 census he is listed as School Master. He ran a school for children which was located a short distance from Deerpark, at a little chapel called Mount Horam or Oram. He had left the farm to live with Henry and Mary Grose because his mother was not in the best of health and couldn’t attend to two men. As Elijah later said, “It was too much work for her,” a statement which was not challenged. Both he and his mother said that there had been no quarrel and he regularly returned to help them on the farm. There were, however, contrary rumours that he and the old man sometimes quarrelled.

The Inquest

The inquest into the death of William Kendall began on the 21st April 1851.

It was a long and detailed case involving many witnesses who testified what they knew of the circumstances. There were many inconsistencies between the evidence provided by Elijah Teague and some of the other witnesses and it soon became apparent that he was the only suspect in a case which looked increasingly like murder.

John Carlyon, the Coroner, drew the jury’s attention to these inconsistencies but, importantly, he also emphasized that in all of the evidence given, no motive had been identified.

The jury were reminded of the importance of their role and then instructed to retire to consider their verdict. How long that took is not recorded but when it was announced, it was unanimous:

“Willful Murder against Elijah Teague”

Elijah Teague had been accused of William’s murder by beating him with a hammer and he was taken to the County Jail to await trial at the next assizes.

On the 1st of May, The North Devon Journal carried this headline:

Murder Near Truro

It has happily been some time since the frightful crime of murder has been perpetrated in Cornwall; but we are sorry that we have again to add to the catalogue of heinous guilt, a murder committed in this county on Saturday last. The locality where the deed was perpetrated is called Silverwell, near the Chiverton Arms, on the road between Truro and St Agnes, and about five miles from the former place.

The Trial

Elijah Teague’s trial began on Wednesday the 6th of August 1851, at the Crown Court under Lord Chief Justice Campbell. The courtroom was crowded with people clearly anxious to hear the proceedings.

The jury was sworn in with Samuel Lobb as the foreman. Mr Stock appeared as Counsel for the prosecution and Mr Collier appeared as Counsel for the defence.

To help understand the area in which the events took place, Nicholas Whitley, a land-surveyor, produced a plan and a set of notes to help identify the location (unfortunately this is not available):

The road leading from Truro to St Agnes is about eight miles.

From Truro to Chevelah is about two miles.

Nearly a mile beyond Chevelah, the road diverges to St Agnes and Chacewater [some may remember this as Stickler’s Corner and more recently as Maiden Green Roundabout].

From John Hore’s house, on the St Agnes road, it is about a mile and a half to Chacewater by a road across the country.

About one-eighth of a mile further on the St Agnes road, is a lane to the right which leads to a croft and one of the paths leads to the Kendall’s house.

It is about three-eighths of a mile from there to Henry Grose’s house.

The Clerk of the Court addressed Elijah Teague, “You are indicted for the wilful murder of William Kendall, on the 19th of April, in the parish of Kenwyn, by striking and beating him with a hammer, giving him a mortal wound in the head, of which he died. Are you guilty or not guilty?”

Elijah replied in a firm voice and without the least sign of emotion, “Not guilty”.

The witnesses were then ordered to leave the Court, and to remain until called.

Mr Stock opened the case for the prosecution by addressing the jury, stating that it was clearly a case of murder which the evidence would show had been carried out by the prisoner at the bar. He impressed on them the solemn and important nature of the inquiry and said, “It was one of the most solemn and awful in which men could engage”. He also said that the case was made more difficult because it was based on circumstantial evidence.

Mr Collier, the Counsel for the Prisoner reminded the jury that no man should be condemned lightly or on mere suspicion, when the consequence is the forfeiture of his liberty; still less when it is the forfeiture of his life. He went on to say that even in these times, when juries are so cautious, mistakes sometimes occur; the innocence of the accused is discovered after they have been convicted, and they are released from imprisonment, or recalled from transportation; but there is one sentence, and one only, which cannot be recalled, and that is the sentence of death. The gentlemen of the jury must be cautious in the discharge of the responsible duty which had fallen upon them.

The evidence given at the inquest and the subsequent trial has been consolidated here and structured sequentially, as far as possible, to provide a transcription which, it is hoped, makes it easy to follow.

Elijah Teague’s Evidence

I live with Mr and Mrs Grose, in Butt Lane, not far from my school at Mount Oram Chapel.

William Kendall had asked me to go to the farm on Saturday the 19th of April to help with the work.

By the time I arrived, William had already gone to Chacewater.

I spent my time thrashing corn and boiling turnips for the pigs.

About eight o’clock, my mother left to go to Henry Grose’s, and I followed her shortly after.

I caught up with her and she told me that there were sheep in a seeded field and asked me to go back and chase them out.

I went to the field and my mother continued on her way to the Grose’s.

I began to chase out the sheep but before I had finished, I heard our horses making a commotion.

I then heard a gate fall.

I finished chasing out the sheep and went up to check on the horses and to replace the gate.

I found the three horses near the gateway including the one which William had ridden to Chacewater: it was still saddled. The horse was generally kept fettered but only one end of a fetter was fastened to her fore leg, the other end was loose. Until then I didn’t know that William had returned from Chacewater.

I then spotted William lying on the ground: he had a large wound in his forehead and was not responsive.

From the time I left my mother to drive out the sheep until I discovered William on the ground was between a quarter and half-an-hour.

I lifted the old man with his back towards me and half-carried, half dragged him into the house, a distance of about eighty yards.

I did not put him down until I placed him on a chair in the parlour.

He did not bleed much after I picked him up.

I was about to go for help when I met my mother and my niece in the doorway.

In reply to my mother, I said that William had returned, that he had been thrown by a horse, and that he was in the parlour.

I prevented my mother from seeing William because he was very poorly and I was concerned that the sight of him would frighten her.

My mother called out two or three times, “My dear Kendall, can you speak to me?”

I thought I heard a response but could not be sure.

I told my mother that one of us would have to go for the doctor. If I went then she would have to remain with William.

She told me that she would go to Truro for the doctor and about ten minutes later, she and the child left.

I then boiled some water, poured it into a tub, and placed William’s feet in it. After an hour or more, I was uncertain how long, no help had arrived so I lit a piece of candle, left it burning in the parlour and left for Truro to fetch my brother, my brother-in-law and a doctor. I locked the door and thought I put the key over the stable door but I’m not sure.

On my way to Truro, I had some attacks of cramp and had to rest against a hedge. I then met a young woman – in the valley between Capt. Hamley’s new house and Chevelah. She was also heading for Truro, and she agreed to tell my brother and brother-in-law what had happened. I didn’t mention the doctor because I thought I could get one sooner from Chacewater. I turned and headed for Chacewater and after I had gone a short way, a carriage drawn by two horses overtook me and I got up behind it. It went on the St Agnes Road, and I got off near John Hore’s and walked from there to Chacewater by the Great Road.

I reached John Moyle’s, the doctor, about midnight. I asked him to visit the farm to attend to William Kendall who had received a kick from the old mare whilst he was in the act of fettering her. I asked if my mother had been there but she had not, so I guessed she had gone to Truro – as she had said she would. John Moyle told me that he had a previous engagement and that he would call as soon as he could. He told me to go back and apply a cold, wet cloth to the wound. I told him that I was afraid to go home and that I had locked the old man in.

I returned to the farm, took down the key from over the stable door and went into the house. Everything was as I had left it, albeit the candle had burnt out so I lit another with a Lucifer match. I think the fire had gone out, so I lit it again. William’s feet were still in the tub, but the water was nearly cold. I took some of the water with a little wooden dish, washed William’s face and then threw the water into the court. I then put my hand under William’s legs to lift them up so that I could remove the tub but didn’t lift them high enough and spilt some of the water. I added warm water to what was left in the tub and placed William’s feet in it again. I put a wet cloth over his head as Mr Moyle had ordered and I thought I could perceive a little breath in him, but I cannot swear that I did.

I remained there only a few minutes and then went down to Henry Grose’s for help. I locked the door when I went out but whether I left the key in the door or in the hedge, I don’t recall. It was sometimes left in the hedge and sometimes over the stable door.

I arrived at Henry and Mary Grose’s place, where I lived, and found that they already knew about William. My mother had told them so I knew then that she had not been for the doctor.

Henry Grose and I went to William Sandoe’s, but he and his wife were in bed and so the two of us continued to Deerpark. We went into the parlour where we found William still in the same position. It was not clear to either of us whether he was dead or alive. We remained there for three or four hours and did nothing more than place a wet cloth over William’s head and put his feet in warm water.

On Saturday morning, probably about five o’clock or six o’clock, I went again to fetch Mr Moyle. I told him that Old Mr Kendall was dead and asked him to go to the farm. I asked him if he was going to ride or walk as my brother’s trap would be there and he would drive him down.

I was with John Cocking when John Moyle arrived.

During the trial, I was shown some clothing and I confirmed that the trousers were mine – the ones I wore all last week. The two shirts, necktie, coat, and pair of shoes were also mine. I didn’t know which of the shirts I wore last Saturday, but I wore one of them and the other clothes. The waistcoat I wore is at my mother’s where the jury saw it. It was noticed that there were a few spots of blood on the trousers but none on any other part of the clothes.

Mary Kendall’s Evidence

William needed someone to go to Chacewater and I said, “you go on to Chacewater, my dear, and the boy will do the thrashing”.

William left home to go to Chacewater about six or seven o’clock. He generally returned home by way of Butt-lane.

Elijah finished work about eight o’clock and we both set out to go to the Grose’s. I left just before him.

When I had reached the Croft, I looked back and saw Elijah walking after me.

Just before he reached me, I spotted some sheep in a field which had been seeded for grass. I told him to go back and drive them out and he did so.

I continued on my way to the Grose’s. I intended to return with my grandchild (my daughter’s, daughter) but Elijah didn’t know that.

I remained at the Grose’s for maybe an hour and then returned home with my granddaughter. We entered the house and Elijah was standing there.

I asked if William had returned.

On hearing that he had, I asked where he was. Elijah said that he was in the parlour.

I went towards the parlour but Elijah put his hand on the door and said that William had been thrown by the horse. He said he was very poorly and the sight of him would frighten me.

Instead, I called out two or three times, “My dear Kendall, can you speak to me?”

I thought he made a sound but could not be sure.

Elizah said that either he or I would have to go for the doctor and I decided that it would be me.

We headed down through the Croft, the little girl and me, but when we got to Butt Lane Gate, I felt faint. I stopped there for a minute or two and was so unwell that I could not carry on so I headed for the Grose’s.

We arrived there just before 9.00pm and I told them about the accident. I asked her to go up to the house and she said that she and her husband would but first they would ask their neighbour, William Sandoe and his wife, if they would go with them. Mary Grose told me to remain at her house.

As soon as they left, I decided that I could not stay there and I set out for home. I reached the house before them and walked up and down until they arrived. We then found that we couldn’t open the door. I tried to find the key, but it was not in any of the usual places. I then suggested that we get a pick and lift the door off its hinges, but this was not approved of. I then proposed to take out a pane of glass, but nothing was done. Then, when we found that we could not get into the house, we all returned to Henry Grose’s.

We always kept the horse fettered to prevent it from jumping hedges and kicking the other horses, but I have never heard William say that he was afraid that it would kick him.

Henry and Mary Grose’s Evidence

We live not far from the Kendall’s, in Butt Lane, near Mount Oram Chapel.

Elijah Teague left our house on the Saturday morning.

Mary Kendall arrived at our house about 7.00pm and stayed for about an hour. She then went home and came back a little before 9.00pm. She was very frightened. She told us she believed that the mare had thrown her husband, and that she was not sure whether or not he was dead. She asked us to go to her house and I said that we would first call a neighbour. We called William Sandoe and his wife and went up together. We left Mrs Kendall at our house, but when we arrived at her place she was already there – waiting outside.

We found the door locked, and being unable to find the key, we all left. William Sandoe and his wife headed for their house in Butt-lane and Mrs Kendall came into our house with us.

Elijah returned home about midnight and asked if we had heard that the horse had thrown William Kendall. We told him that we had heard it from his mother. I (Mary) thought he was wearing the same clothes as when he had left.

Elijah told us that he had been for the doctor who had promised to come as soon as he could. He and I (Henry) then went to William Sandoe’s, but he and his wife were in bed so Elijah and I went to Kendall’s house together. It must have been after 1.00am and Elijah went straight to the door and unlocked it. I don’t know where he took the key from – the stable is at the western end of the house – I am quite sure he did not pass the house door before he unlocked it.

I saw the deceased in the parlour sitting in a chair, his head lying back. He appeared quite stiff, and his arms were hanging down by his sides. I merely looked inside the parlour door: I did not go into the room. There was no light there at first, but Elijah lit one soon after we got in. After about three-quarters of an hour I went into the room and Elijah went with me. He had been lighting a fire and neither of us had gone into the room before. William Kendall was dead and stiff and had a wound on his forehead. There was some blood on his face but not a great quantity. His feet were in a tub of water. He was in the south-west corner of the room. I held the candle whilst Elijah wiped some blood from his face with a bit of wet cloth. The blood that was there was nearly dried up. Elijah described the way in which he took the deceased to the house and then showed me the spot where he had found him. He did not appear to be much upset about what had happened. We stayed for three or four hours.

My husband (Henry) and William Sandoe went to catch a pony so that my husband could ride to Truro. After they had gone a short while, Mrs Sandoe and I picked up the saddle and went to meet them. Mrs Kendall joined us after we got to the lane. We couldn’t see them and were returning to the house when they heard us talking and called to us. They had the pony, but my husband did not ride it: he put it in our stable.

After daybreak, Mrs Kendall and I (Mary) went to her house: it was about 5.00am. On our way, we met my husband who said that William Kendall was no more and that he was going to Truro. We continued on and met Elijah at the house. Mrs Kendall went upstairs and I stayed down below. I didn’t go into the room where the body was. Before we reached the house, we thought we had seen a light, but we could not see it when we got there. Elijah then went to Chacewater again to fetch Mr Moyle.

William Sandoe’s Evidence

I live in Butt Lane and am a neighbour of Henry and Mary Grose.

I shone a light through the window and must have seen the body in the parlour if it had been there.

If he had been at the same place in the room where I saw him next morning, I must have seen him.

William Chenhall’s Evidence

I am a miner living at Penstraze, about a mile from Deerpark and on the road from Chacewater to there.

I saw William Kendall at about 8.15pm on the 19th April, he was riding a light grey pony going towards his house. He was going a little jog-trot and when he came opposite my house, he pulled up and we spoke. I said, “I suppose, sir, you are coming from market at Chacewater,” and he said he was. He was sober, and seemed very well – in his usual health. Going at that jog-trot pace, it would have taken from between 10 minutes and a quarter of an hour to get to his house.

Ruth Bawden’s Evidence

I am Richard Bawden’s daughter and I live with him in the parish of Kenwyn – near the Truro and St Agnes turnpike road.

I was coming home from Truro market on the 19th April and as I crossed the common to my home, I saw Mr Kendall. He rode across the road at Penstraze Moors; he was coming from the direction of Chacewater to the Truro and St Agnes Road. He was riding a pony towards his home. When I last saw him, he had passed William Chenhall’s house, near the turnpike road, and riding on at a gentle trot. I then went home – it was about 8.15pm.

David Chenhall’s Evidence

I was a member of the inquest jury.

On the Saturday night, I was on the road leading from Chacewater to Kendall’s: going towards his house and towards my home.

Elijah Teague overtook me – that would have been about 12.30.

I had known him for many years and he told me that the old mare, which I had sold them, had either kicked or thrown Mr Kendall.

I asked him where she had kicked him and he said that it was in the forehead.

He told me that there was no one at home. I asked him where his mother was and he said that she couldn’t get in because he had the key.

William Kendall had had the mare for about twelve months and while she was with me, also about twelve months, she was very quiet and easy to handle. l have never known her to kick although she did kick up her heels against me on one occasion – or try to. My wife told me that she had lapped up her heels against her on the same occasion – when I went to drive her out of some grass.

Jane Hobbs’s Evidence

I am the wife of Matthew Hobbs, shoemaker, living at Castle Hill, Truro.

On the 19th of April I was at St Agnes and left there by the turnpike road a little after 8.00pm to return home. I had reached Capt. Hamley’s, at Chevelah, when a young man, a stranger, came up to me. It was then about 9.30pm. He asked me whether I had seen a woman pass that way and I said I had not. He asked the same question of a man on a carriage and he responded that he hadn’t seen her either.

The young man then followed the carriage and I continued to Truro as fast as I could. When I arrived there, I heard the clock strike ten.

I cannot say that the young man did or did not give me any message to take to Truro, I may not have noticed every word that was said.

John Moyle’s Evidence

I am a surgeon practicing at Chacewater – a position I have held for more than fifteen years.

I was the Kendall’s doctor until they transferred to Mr Bullmore at Truro.

Elijah Teague called at my house on the Saturday night at about midnight. He asked me to visit Mr Kendall who, he said, had received a kick from the old mare whilst he was in the act of fettering her. He asked if his mother had been at my house. I told him I had not seen her myself and neither had I heard of her having been there. He then said that he supposed she must have gone to Truro. I told him I had a previous engagement and that I would call as soon as I could. He said that William appeared to be stunned by a blow and had sustained a small cut in his forehead. He then pointed out with his finger on my head where the cut was – over his right temple. Supposing it to be a slight case, I requested him to go back and apply a cold and wet cloth to the wound. He replied that he was afraid to go home, that he had locked the old man in, and I think he added that he had the key in his pocket, but I cannot be positive as to that. He asked me if Kendall died, would the old mare be knocked in the head, and I told him I didn’t know.

Elijah Teague called at my house again just before 6.00am on the Sunday. He told me that Old Kendall was dead, and he asked me to go to the farm. He asked if I intended to ride or walk as if it was the latter, he expected that his brother’s trap would be at Mr Kendall’s and that he would drive me down, meaning back.

I rode over on horseback by way of Butt Lane. When I reached near the north-west end of the outer lane of William Kendall’s premises, I saw Elijah Teague and John Cocking standing there together. Cocking drew my attention to a few spots of blood on the roadway where the body was said to have been found. I didn’t examine them closely then but rode on to the house where I found Mrs Kendall in the kitchen sitting at the east end of the table and Mary Grose sitting in the large chimney, or near it. I asked if Mr Kendall was upstairs and I believe they both said, ‘No, he is in the parlour’. I turned round, opened the parlour door and saw him on a chair in the southwest corner of the room. He was covered with two coats, an old cloak, and an old waterproof overcoat. On removing the overcoat, I recognized the deceased to be William Kendall who had been known to me for at least fifteen years. I examined the wound in his forehead and concluded that it was not caused by a kick from a horse but that it had been inflicted by two or more blows from some heavy instrument and that either of the blows would have caused his death. The first blow must have rendered the deceased insensible and unconscious. I do not think that he could have breathed for more than two hours after the blow had been inflicted, and possibly less. I stated this to John Cocking and Elijah Teague.

The room was in a disordered state. Near the feet of the deceased stood a tub containing water – not bloody. The floor under his legs was very wet, and on the north side the wet spot had a shading of blood. There was a small spot of coagulated blood on the floor, near the back of the room. The deceased’s shoes were near this spot; I examined them and found on the outside of the left one a small spot of blood which had fallen on it. The right one was stained with blood on the inside near the heel, which appeared to have been mixed with sand. The only offensive weapons I could discover in the room, and which I examined in the presence of Cocking, were two pokers, a fire shovel, and a flat iron, but neither of them had been offensively used.

I waited a considerable time whilst the premises were being searched for the purpose of endeavoring to find an instrument likely to have caused such a wound and went out myself and again examined the place where the deceased was said to have been found. On my way back to the house I took the hammer from the garden hedge. Attached to the small end of it I found a strong white hair, which I now produce. I then applied the hammer to the wound in the presence of the coroner and jury and found that the small end of it accurately fitted the right side of the wound, and very nearly corresponded with the left side of it, which I believe was caused by a second blow. The wound was situated near the centre of the forehead and was of an irregular oval figure. The integuments were very much lacerated or jagged and torn, and so much depressed with the bone, that I readily inserted my finger on the right side, to the depth of nearly an inch. After removing the scalp, I traced the size and shape of the opening in the frontal bone. I then removed sixty-one pieces of bone. The blows must have been given with great force, evidenced by the fact of there being no fissures radiating from the opening into the bone, and from the great depth to which they had been driven – an inch and a quarter below the surface of the skull. The dura mater [one of the layers of connective tissue that make up the meninges of the brain] was not torn. The longitudinal sinus was not opened. [The large blood vessel running from above the root of the nose over the head between the membranes of the brain]. Perhaps this will account for so little blood having been seen.

I examined the hair found on the hammer and was of opinion that it is a human hair from the eyebrows of an aged person. I removed several hairs from the deceased’s eyebrow and examined one with the aid of a microscope. My opinion is that it resembled the one I took from the hammer – I believe it to be a human hair which had been forcibly torn from deceased’s eyebrow. I saw no blood on the hammer when I took it into the house.

I went with Cocking and Elijah Teague to examine the spot where Elijah had said he had found the deceased. I saw five small spots of very dark coagulated blood, perhaps together amounting from one to two table spoonfuls. They were isolated spots, having an average intervening space free from blood of from eight to ten inches. I expressed my surprise at seeing so little blood from so large a wound in the forehead. To this observation I received no reply. The blood had only slightly stained the ground and I didn’t think it could have flowed from a recent wound.

I asked Cocking to cover them, first with a gate and then with a faggot of furze. To the best of my belief, there was no loose furze or browse in the lane immediately near the spots of blood. I was shown a hat which Elijah Teague said belonged to the deceased – it had been lying in the road all night. It did not appear to be injured.

With regard to the suggestion that William had been dragged, I found no traces of a heavy body having been dragged along the ground.

After examining the place all round to see if I could discover anything to throw a light on the case, I returned to the house and requested that the deceased should not be removed from the chair until he had been seen by the coroner and the jury.

When I stripped the deceased in the presence of the jury, I found no marks of violence on any part of the body except the head. I had the hind shoes removed from the old mare, and, at the request of Richard Teague, Elijah Teague’s brother, one hind shoe from the colt. I applied these to the wound on the deceased’s forehead in a variety of ways but neither of them corresponded in shape or size with the wound.

John Cocking’s Evidence

I live in Kenwyn, about 200 yards from Deerpark.

Elijah Teague came to my house at about 5.00am on Sunday the 20th of April. He asked me to go to Deerpark to be with his mother while he went to Chacewater.

We examined the ground, and I considered that the five spots were clotted blood. John Moyle moved them with a penknife and noticed that they had not soaked into the dust.

I saw no marks of a heavy body having been trailed or dragged along the road.

On the Sunday morning, about six or seven o’clock, I held the horse by the head whilst the other span was fastened to its hind leg. Mr Moyle was present. Elijah explained that sometimes the deceased fettered the horse and sometimes he did. He said that he had fettered it before without anyone holding its head, but not when the other horses were near.

I was at the Kendall’s house between 7.00am and 8.00am on the Monday morning with Elijah Teague. He asked me whether I was to be one of the jury and I said I believed I was, as I had seen my name on the list. Elijah said I think you will bring it in as an accident.

I think the Kendalls keep goats but I didn’t see any goat skins on the hedge where the hammer was found nor did I see any dogs playing with any.

Edward Michell’s Evidenc

I live at Tregavethan, about an eight-minute walk from Deerpark.

Elijah Teague came to my house on the Sunday evening – between six and seven o’clock. I told him that I had already heard about William. I asked him why he had not sent for me, or someone else, earlier and he said he had not known what to do.

I asked him where he was when it happened. He said he was down the lower side of the field driving the sheep out over the hedge when he heard a racket with the horses. He went up to check on them and saw three horses there and the deceased lying near them. He told me that he had spoken to Wiliam but could get no answer.

I asked him how he got the corpse into the house and he said he had put his arms round his waist and carried him into the kitchen. He placed him in a chair near the fireplace; but found that he was slipping so he put him in an elbow chair in the parlour. That is all I heard that day.

I saw Elijah in the evening of the day he had come from the inquest. It was in Kendall’s house, between seven and eight o’clock. He asked me to hold the candle whilst he was putting his brother’s horse into the gig.

I said to him, “Elijah, how can you stand all this, for I believe you are guilty”.

He replied, “What is the use to take fear before fear comes”.

I told him I would not be summoned to sit on the jury on any account for my mind told me he was guilty. He made no reply to that.

I said that I had heard that the body was almost drained dry, that there was scarcely any blood left in it and he told me that William had lost a great deal of blood whilst he was in the chair and that he had dipped it up in a tub.

I asked why he had left that old hammer where he did and he said that it was under no concealment and that it mattered nothing.

I told him that I had heard that there was hair found on it and he said that it may have been goat’s hair. There may have been goats on the premises and I believe that one had been killed on the Friday.

I was on good terms with Elijah as with my own son. I had, some time before, accused him of killing a fowl of mine but he said that my son did it; this might have been a month or five weeks before. My son went to his school at Mount Oram, and continued to do so after the affair of the fowl

l was not on very friendly terms with Old Mr Kendall but was with his wife: she and Elijah used to come to my house.

I have no ill-feeling against the prisoner and I never said after the affair about the fowl, that I would serve him out.

Nancy Michell’s Evidence

I am Edward Michell’s daughter and I live with him.

Since Mr and Mrs Kendall’s marriage I have become acquainted with her and Elijah. They both visited my house but Old Mr Kendall had only been there once. My father was not on very good terms with him.

Elijah had often told me that he and Mr Kendall could not agree and that the old man was very cross to him. He said that they used to have words sometimes. Both before and after Elijah went to Grose’s to live, I heard him talk in this way. I think I have heard Elijah say that he went to Grose’s because he and Mr Kendall could not agree.

I recollect Elijah coming to our house between six and seven o’clock in the evening of Sunday the 20th of April, the day after the old man’s death. He asked me to go to Kendall’s to be company for his mother and I did.

Alfred Lord’s Evidence

I am the clergyman for the Mithian district and a former medical man who received his medical education at St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

I was present at the post mortem examination on the Monday and also at the inquest.

I examined the wound on William Kendall’s head and came to the same conclusion as John Moyle.

I was present when the hammer was taken off the hedge by Mr Moyle and saw him remove a hair from it.

I know the spot which the prisoner pointed out as the place where he found the body. The road leading to the house was rather dusty and by the time I saw it, it had rained. I saw no evidence that a body had been dragged along it.

It is my opinion that the wound in the deceased’s forehead could not have been caused by a fall on a stone or by a kick from a horse but I cannot swear that it was impossible to have been so caused. A blow given with the shoe of a horse would have extended over a larger surface, and would have driven in a larger portion of the skull.

Richard Quiller Couch’s Evidence

I am a member of the College of Surgeons and I live in Penzance.

I examined the hair under a microscope and considered it to be human. It was broken in the outer part, as if it had been squeezed between two blunt edges.

Mr Stock, Counsel for the Prosecution

Mr Stock referred to the improbability of Elijah Teague’s statement and pointed out its inconsistencies.

He said that the evidence showed that William Kendall did not come to his death at the spot that Teague had stated; that the blood had been placed there; that the wound in the deceased’s forehead was not from the kick of a horse but was caused by a hammer and that there was no indication that a body had been dragged over the ground.

He also referred to the conduct of the prisoner on the night William Kendall came to his death as that of a man with the consciousness of crime, going in different directions doubtful what to do, and “unprepared at the moment with a statement to exonerate himself from suspicion”.

He characterised the conduct of Mary Kendall and the neighbours in not entering the house where Mr Kendall lay, as extraordinary.

Finally, he acknowledged the difficulty of not being able to show a motive for the murder.

Mr Collier, Counsel for the Defence

I place great store on the fact that the counsel for the prosecution has referred to great difficulties in the case, and that one of these is the lack of any motive for the crime. Men do not commit great crimes without a motive; even hardened ruffians, whom crime has made callous, shrink from the shedding of human blood. Would a youth, unstained by crime, commit his first crime in so atrocious, so cruel, so incredible a manner. Why would he murder the old man? He had nothing to gain by his death especially as the old man was his employer.

The prisoner is an industrious young man who has endeavoured to obtain his livelihood partly by keeping a school, and partly by occasional employment as a workman. He was working for this old man, whom it is alleged he murdered. He must be rather a loser than a gainer by his death.

A witness has said that William Kendall and Elijah argued and that they were cross with each other. But friends have words, fathers and mothers have words, brothers and sisters have words, but they do not murder each other.

Mary Kendall was overcome by her feelings when giving evidence. She had the deepest affection for the old man and said, “He went out, and I never saw him again alive”. If she believed him murdered, she would not have withheld any evidence. Her statement was that Elijah went to lodge at Grose’s in consequence of her illness, because she was in a weakly state and could not attend to both the men. The jury saw her in the witness box, and it was clear that she is in a weakly, nervous state. She said, at the time of the old man’s death, Elijah and he were on perfectly friendly terms, and he was working for him that day. No motive, therefore, could possibly be assigned for the commission of this crime by the prisoner. There is an old saying, that no man on a sudden becomes desperately wicked. Wickedness proceeds by slow degrees and it is long before a man reaches the crime of murder. But here is a youth perfectly unstained by crime, who is said to have committed this horrible crime. Look at him, does he look like a murderer? He is not rude, not brutal, not uneducated. He has read and taught the contents of the sacred volume, and read and taught the commandment, Thou shalt do no murder. Why should he break that without a motive?

I hope that you or I are never placed in the awful circumstances in which this youth was placed that night. Who shall say how we would conduct ourselves under such circumstances; and give an accurate account of what he did every hour of the time, and of what occurred, so as to bear the scrutiny of a counsel some months after? I can conceive of no position more awful, than in the still hours of the night to meet with a man who has experienced some violent injury, especially if there is some doubt, from appearances, whether it be the result of an accident or by the hand of a murderer. Who knows that under such circumstances he should do what is most prudent? Who knows that he should go to the first place to get assistance, or ramble somewhere else? The counsel for the prosecution speaks of distraction of mind being evidence of guilt. Is there then no distraction produced by other causes? If distraction shows only guilt, God help the innocent and the afflicted. I have always understood that great calamities, sudden afflictions, wisht occurrences, tend to distract a man as much as guilt. Is it to be supposed that because this young man was distracted, he is guilty? And when it is pressed against him, whether he took the key and put it in his pocket, and that he is not quite right to half an hour as to where he went and that he said something which is not consistent with what is said by other witnesses – it is bearing rather hardly on him. Who shall say how he would conduct himself under such trying circumstances? it may be that many persons against whom suspicion has arisen, have taken exactly that course which leads to suspicion. A suspected person, though innocent, may sometimes state what is false. An innocent man has not always the boldness, the resolution to state the whole truth. That has been evidence against him, and on that ground, juries have sometimes been mistaken, and confounded the innocent with the guilty. The distraction which may be produced by calamity, by affliction, by guilt, may be produced also by a false accusation, which tends to confuse the mind, so that a man does not know what he says or does.

Elijah Teague made a statement before the coroner without any degree of unwillingness and that statement has been confirmed in almost every material circumstance. Almost all the points on which the prosecuting counsel relied, have failed; and if a verdict of guilty can be returned at all, it must be based entirely on the evidence of the medical witnesses. I do not attribute to those witnesses any improper motive, but that they may be mistaken.

Elijah Teague has never varied his account of the occurrence in any material way. My learned friend may be able to point out some minute differences between the story he gave to one person and to another. But that was what can be expected. If any one of you were to give an account of an occurrence to half a dozen different persons, you would not tell the story to all alike; you would add something to one which you did not tell another, or he would omit something. So it is, no doubt, in the present case. But supposing Elijah Teague had given precisely the same statement to different people as he had given in his deposition; my learned friend would then have said, he had manufactured his story and repeated it by rote. At present, however, his statements are just those of a person who was agitated, and could not give to every person a perfectly satisfactory account of what had occurred, but stated to the best of his knowledge and belief.

Consider Elijah Teague’s statements which have been confirmed by the other witnesses. The fact that he was sent back by his mother to drive out the sheep from the seedling grass was confirmed by his mother. If Mrs Kendall had not sent him back, he would have continued with her to Grose’s and would not have been at home when the old man returned from Chacewater. There was evidently no lying-in wait for the old man: it was by sheer accident that Teague was there when he returned; and he had every reason to believe that his mother would soon return from Grose’s. It was also an entire accident that the old man went to Chacewater at all as from Mrs Kendall’s evidence she had told him that he should go and leave Elijah at home to thrash; otherwise Elijah would have gone to Chacewater instead. It was also an accident that Elijah was at home when he returned; he would not have been there if his mother had not sent him back to drive out the sheep.

As to Elijah’s graphic account. You can almost fancy yourselves in his situation, hearing the neighing of the horses and the gate falling. It was at that gate that the accident no doubt occurred, though probably not by a kick from one of the horses. Nor does Elijah Teague say that he saw the old man kicked, but seeing the mare unfettered, he naturally concluded that old Mr Kendall had been kicked. But the accident may have happened differently. William may have been galloping up at a great pace, and the other horses rushing down to the gate, he may have been thrown with great violence onto the ground, thrown on a sharp stone, or on two stones together, as I put the case to the witnesses. Mr Moyle examined some of the stones in the road to see if there was blood on them but he has not compared any of them with the wound. I have been struck now and then with the appearance of a stone in the road, which might have produced such a wound as was made in Mr Kendall’s forehead. Mr Moyle thinks the wound could not have been so produced and the medical witnesses say that the wound was produced by great force. But who knows with what force he may have fallen? He may have come galloping up to the gate and been thrown to the ground with immense violence. I do not know whether you, gentlemen, have ever known of such an accident, as that of a man having fallen in that way, and had the bones of his face smashed; if you have not then evidence of such a case can be produced before you. You are not, therefore, to be bound by the opinions of the medical men: the verdict is yours – you may be right and they wrong, and you may save the innocent.

If Elijah Teague’s account is not true then it must have required immense talents to concoct such a story.

It has been said that there were no marks on the road which suggest that a heavy body has been dragged across it. But a heavy body was not dragged over the road. The old man was only six or seven score. Elijah Teague said that he lifted him and carried him as best he could, his heels dangling down, sometimes touching the road and sometimes not. In this way, the road being in some places dusty and some places stone, I doubt that you would see any track at all. Besides, we are told that there was furze and grass by the side of the road which Elijah may have walked over. Mr Moyle referred to furze prickles sticking to the old man’s coat and that tends to explain he was dragged by the side of the road where the old man came in contact with the furze. My learned friend would have you suppose that this old man came home sound and well, and that this young man went and deliberately murdered him in his house. But he came home on horse-back, and one does not see why he should have furze on his coat, unless in the way I have described. It is a trifling circumstance, but if my learned friend relies on trifling circumstances to affect this young man’s life, I am entitled to rely on trifling circumstances to show his innocence. As to marks being expected on the road, it must also be remembered that there were half a dozen persons going about the road that night, Mrs Kendall, Grose and his wife, and Sandoe and his wife, the whole party distracted, looking for colts, mistaking whitewash for a light, going backwards and forwards not knowing what they were about; so that if distraction were evidence of guilt, they are all guilty. With all these people going backwards and forwards, if there had been marks in the road they would have been rubbed out. Mr Moyle himself had ridden over the place, horses had been running about; so that you see how cautious a jury should be before they find a verdict on such slight and equivocal evidence. What would be your feelings if you should convict this young man, and find out afterwards that you have been mistaken? Where would he be? His body gone to the earth, his soul gone unprepared, possibly to his last account, and there would be no revelation. I beseech you to weigh cautiously these slight circumstances to which I draw your attention.

A drop of blood, it is said, was found in some sand in the heels of the old man’s boots, and it is very possible that as he was partly pulled, partly carried, a drop or two of blood may have fallen onto his boots, and the sand have also got into them in that way. Teague says the distance he took the old man was about eighty yards, and the place he points at, turns out to be seventy-two yards from the house.

Elijah Teague would not allow his mother to see the old man in the parlour because he was afraid it would upset her. You have seen this woman in the witness-box, and it is evident she is in a delicate state of health, and so highly excited that she was taken from this court and conveyed to her bed. This young man knew that the sight of her husband with the wound in his forehead would have terribly excited his mother, and he prevented her from going in. If she had gone into the room, she would have probably fainted, and he would have had the trouble to attend to two instead of to one. When the wound was spoken of in court, it greatly affected the poor woman, and how much more would she have been affected if she had seen it. The suggestion on the part of the prosecution was that Elijah Teague had murdered this old man and then kept his mother out of the room so that he might first put all right there. Mary Kendall’s granddaughter has testified that Elijah said, ‘You shall not go in mother, for you will be frightened’.

Mary Kendall said, “Elijah was standing by me and said, you must not go away, you must stay here or go for the doctor”. By this he gave her the option of either going or staying, and if she had recovered from her fright, and kept house whilst he went for the doctor, this young man would never have been at this bar. It was because of her going that these suspicious circumstances arose against him. Every man is open to suspicion when found near the body of a man believed to have been murdered.

Another point pressed against the prisoner was of him going so far as Truro for a doctor when he could have gone to Chacewater. But Mrs Kendall has said that she used to employ Mr Moyle of Chacewater but, for some reason, decided to use Dr Bullmore of Truro, instead. Although he had only visited her once, he had often sent her medicines, and it seems that it was she who suggested that they should fetch the doctor from Truro. It would have been better to have gone to Chacewater under such urgent circumstances; but who can tell what they would do in a similar situation?

Elijah Teague may not have known how serious the situation was but he knew the old man was in a bad state and could they wonder that he could stand it no longer and should, after waiting an hour or two for his mother to return, head for Truro to fetch Dr Bullmore. In moments of intense anxiety, minutes and hours are not counted; every minute you are considering your verdict will be like an hour to the prisoner.

My learned friend said the woman who Elijah encountered on his way to Truro stated that he gave her no message to fetch his brother and brother-in-law but when she was called, she was so confused and agitated that she couldn’t remember whether or not he had done so. She did hear him ask another man if he had seen a woman going to or coming from Truro, and by this he meant his mother. It was the case that Mary Kendall had left the house to go to Truro but she has stated that she changed her mind and gone to the Grose’s instead.

Mr Stock, the counsel for the prosecution, has highlighted discrepancies in the stated times by the prisoner but this was to be expected. You cannot rely on a matter of that kind, you cannot say yourselves the precise hour at which a thing happened a week or two ago, you cannot say to half an hour. The witness, Hobbs, said he came up to her in the road to Truro about half-past nine, and that she left St Agnes some time past eight: but she was not likely to walk eight miles in less than two hours; and in all probability the clock at Truro, when she arrived there, struck eleven instead of ten as she supposed. But what does it matter, gentlemen? You are not going to sacrifice a man’s life, on the difference between a clock striking ten or eleven.

The burnt-out candle is probably explained by it being a short piece and the uncertainty regarding the location the key was explained by Elijah Teague. He said he locked the door and put the key over the stable door, where it was usually kept; but very likely, as he afterwards told Nancy Michell, he did not know whether he put the key over the door or in his pocket, but that he found it afterwards in his pocket. What was more natural than his conduct? It was not usual to leave the house without any person in it, without locking the door. He does that, and thinking his mother was gone on to Truro, and expecting her back, he goes to meet her. He thinks he must meet her, and not expecting any other person to come there, he has no idea that he is locking anyone out.

The suggested light in the kitchen window has been acknowledged by the three women as probably a mistake. It may have been whitewash on the wall or the men with a lantern who had gone on before to catch the horse or it may have been reflection from the moon.

Elijah Teague called on Mr Moyle and asked him to come out. Now, a man who has murdered another is likely to be the very last person to call a doctor to come to the person he has murdered and it was not the prisoner’s fault that Mr Moyle did not come at once. Elijah Teague said that Mr Moyle told him to put a wet cloth on the old man’s head, and Jane Sandoe says that Elijah told her that Mr Moyle had given him directions to put William’s feet in warm water. Mr Moyle says he gave no such direction but he may have done so and forgotten it, or this boy may have thought it was a proper thing to do and that Mr Moyle had recommended it. When he put the old man’s feet in hot water, he did not know that he was dead.

Mr Moyle said that Teague did not describe the wound as being as serious as it was. And yet, we find that he told others that Mr Kendall had met with a terrible accident.

Mr Stock has referred to a drop of blood on Teague’s trousers but there had been no attempt to conceal it. It had probably fallen there when he was carrying the old man home.

No doubt the notion of people in general would be, that from a man killed in that way a great deal of blood would flow, and that somebody in this case must have disposed of the blood. That seemed to have been the witness, Michell’s, opinion; for he thought Elijah Teague guilty, because he had heard that the whole of the blood had come out of the old man’s body, and he thought Elijah Teague must have put it somewhere. It appears, however, that there are a number of small vessels in the forehead, and if a blow does not break the longitudinal sinus, there would not be much blood. In this instance It was not broken; so there is an end of the suspicion arising from more blood not having been found.

Other parts of the accused’s statement are probably true: for instance, that he spilt some water when he was putting the old man’s feet into the tub and that he had the cramp in his legs on the way to Truro and was obliged to rest against the hedge. This was very likely, after running about in an agitated state. It was also the case that he had fettered the mare by himself, but not when the other horses were near because they were then fractious. The former owner of the mare conceded that she had turned up her heels at him once or twice.

The prisoner’s statement, made voluntarily before the coroner, bore the impress of truth and if there is some differences between that statement and what he had told the witness Michell, I submit that men who intend to report conversations accurately, often make mistakes; but when it is related by a man who evidently had some feeling against the prisoner, they should be doubly cautious in receiving what he said.

As to the witness, Sandoe, looking in at the parlour window with a lantern on the night of the old man’s death, and saying he must have seen the body if it had been there. It is possible that it was there and he may not have seen it. The window is a casement, the wall some twenty inches thick, and the constables (who tried the experiment afterwards) peering about as they did, could not see into the corner of the room within a foot. Mr Moyle had not recognised the old man until he had the coats taken off him and that Sandoe had said, “If he had been at the same place in the room where I saw him next morning, I must have seen him”. That may have been so, but by that time the body may have been moved a little further out from the corner. Mr Stock contends that when Sandoe looked in, the body was in the kitchen but, earlier, when Mrs Kendall was there, the old man was in the parlour, for if in the kitchen she would have seen him. Sandoe then must have been mistaken.

The prisoner’s statement was confirmed by witnesses in a great number of its circumstances, and was also confirmed by the appearances of nature, namely, by the drops of blood lying on the road where the old man met his death. It is suggested by the prosecution that the prisoner put those spots of blood there. Mr Moyle has said he put his penknife under a spot and took it up, and he concludes because it did not stain the stones underneath, that it had been placed there; yet he has made no experiments as to how deep blood will stain, but he says he draws his conclusions from observing how deep the blood has stained when persons have spat outside his surgery after their teeth were extracted. Very likely those persons spat water with the blood, which would sink deeper, and outside his surgery it may not be the same description of soil as in this road. I believe the blood must have been liquid when it fell there or it would not have been in the shape of a drop. But surely, gentlemen, you are not to convict a man on loose speculations like these which the prosecution has put forward.

As to the hat which was in the road, we recalled the witnesses John Cocking, William Sandoe, and Henry Grose and the latter two said that about half-past ten or eleven o’clock on the night of Mr Kendall’s death, as they were going to his house, they saw it and Sandoe put it on a bush. John Cocking said he saw it again about 6.00am on Sunday on a bush in the hedge, near the place where the prisoner said he found Mr Kendall’s body. This added probability to the fact that the old man was going at a great pace when he fell, and that his hat fell off as he came down. If he had been murdered, we would have expected more damage to it than there was.

The evidence of the medical men is not conclusive any more than the other circumstances. The hammer with which it was supposed the old man was killed, was not concealed and a number of people had handled it before Mr Moyle. There was no blood on it and if it had been washed off then the hair would not have been found on it: it would have been washed away. It is on that hair this man’s fate depends. I have heard of fate hanging on a hair, but had never expected to see it verified in experience. If the prisoner is supposed by my learned friend to be so ingenious and clever as to concoct this story then would he have left the hammer that inflicted the injury so unconcealed, to be found by anybody? There was rust on the hammer but no evidence of any being found in the wound; and having compared the hammer with the diagram of the wound made by Mr Moyle, as far as I can see, and I believe the jury will see the same, the two did not correspond. It seemed to me that the wound was of that irregular shape which would be made by a stone.

I do not believe that Mr Moyle will say that such an injury could not have been produced by falling on a stone. Mr Lord said a fall would not be forcible enough to produce a wound; but of course the force in such a case would depend on the rapidity of the rider, and the velocity with which he was thrown. It was well known that with a horse going rapidly, a man might be killed by only falling on the turf; and by falling on a large stove of a particular shape, no doubt a man might smash his forehead without injuring the rest of his face. Taylor’s “Medical Jurisprudence,” states, “A medical witness is rarely in a position to swear with certainty that a contused wound of the head must have been produced by a weapon and not by a fall”. We may often be in doubt with respect to lacerated or contused wounds, whether a weapon has been used or not and Mr Taylor says, “When the question is, whether an injury has resulted from homicide, or accident, there are many difficulties which medical evidence, taken by itself, cannot suffice to fathom”.

An illustration of this was a case which was tried at the Warwick Spring Assizes in 1808, it was quoted in Taylor’s work. The learned Judge has said that we are not to rest on the authority of Taylor as a medical witness, unless he is placed in the box but I have heard such extracts read in court from this very book. My understanding is that extracts may be read from a work of authority. [The Judge then said that Mr Collier may proceed but observed that the general rule was, that extracts may not be read from a book, if the author be living, and may be placed in the witness-box].

I urge you to consider that if eminent men like Mr Taylor were thus cautious in giving an opinion as to the cause of a wound, how very cautious the jury should be in receiving the medical opinions advanced at this trial. Mr Moyle and Mr Lord differed in their opinions to some degree, and if a third medical witness had been examined on the same points, he might differ from them both. Nothing can be inferred from the hair found at the end of the hammer. Many persons had the hammer before Mr Moyle and there is no evidence that any of them saw the hair. Teague said it may be goat’s hair and there were a couple of goat skins lying on the hedge, and the dogs had been playing with one of them. It is said this was a human hair, and Mr Couch says it is a hair from an eyebrow, which I think is going rather far. But even if it was a human hair, nothing could be concluded from that; we find hairs everywhere – in puddings, in bread, in books, in rooms: they get about in all sorts of places. But who can determine what kind of hair it was? Scientific men are not agreed as to the structure and composition; and if recent discoveries have been made, are we to be governed by them? There might yet be other discoveries, but was this man to be a martyr to science? After all, this hair might be goat’s hair or, if a human hair, it may have belonged to somebody else, and not to the deceased, for if rain fell on the Sunday night, as had been stated, any hair on the hammer before that would have been washed off.

Gentlemen of the Jury, if you have any remaining doubts as to the cause of death then you should not find a verdict which entails death. You should take your escape from those difficulties by pronouncing, as the law allows, a verdict of not guilty.

Lord Campbell’s Summing Up

Gentlemen of the Jury, the prisoner at the bar, Elijah Teague, stands indicted for the wilful murder of William Kendall. He pleads he is not guilty, and it is for you to say, on the evidence, whether you think he is guilty or not of the crime with which he is charged.

It is quite clear you are bound to say he is not guilty, unless the evidence clearly and satisfactorily brings home to your minds that he is guilty; for, as the learned Counsel for the defence says, though there may be some mysterious circumstances in the case which will not be revealed till all secrets are made known, yet unless on the evidence before you, you can safely find a verdict of guilty, it will be your duty to acquit him. At the same time it is my duty to tell you, that if on the evidence you clearly think him guilty, and think you can safely action that evidence, then it is your duty to find a verdict of guilty.

The learned counsel for the prosecution, who opened his case in a very candid and lucid manner, submitted that William Kendall certainly died by violence, and about that there can be no doubt. But the question is how that violence was committed. If Elijah Teague, the prisoner at the bar, had not been examined before the coroner, and had not given any account of his share in the transaction, there would have been great difficulty in making out any case against him. But it is submitted to you that he has given an account which is proved to be false; and as he had the opportunity of committing the deed, you are asked to draw an inference from the false account he gave of his share in the transaction, and to reach the conclusion that he is the guilty party. On the other hand, you have heard the able address of the counsel for the prisoner. He says everything which has been proved in evidence is consistent with the innocence of his client; and he very properly observes, that even should there be some discrepancies and some misstatements, it would not be a sufficient foundation for you to find a verdict of guilty.

Gentlemen, it is quite right what the learned counsel urges upon you, that you – and I wishing to assist you – that we should be most cautious not to be led away by mere suspicion, but that there must be clear evidence of guilt before you should find a verdict of guilty.

The question now, is whether the evidence laid before you is sufficient whereupon you can safely find a verdict.

The learned gentleman who opened this case in a manner I thought most highly becoming, stated that the great difficulty, and it has not been set aside, was that no motive has been discovered on the part of the prisoner. According to some of the evidence, there had been words between the prisoner and Mr Kendall but it has been very properly observed, that there have been words between friends and relations, yet God forbid it should be supposed, after there had been words between parties, and one of them was found dead, that the other should be supposed to have murdered him. According to the evidence of the prisoner’s mother, Mrs Kendall, there had been words formerly between the parties, yet all was comfortable, to use her significant phrase, about the time of the occurrence. Other evidence did not show any recent grievance; and even if there were words, it is not to be supposed they would lead to such a revolting scheme as that of taking away the life of the old man.

Another circumstance to which I will draw your attention is that there seems, as far as I can discover, to have been nothing like premeditation. All, as far as we can see, appears to have been accidental that night. If the prisoner is guilty, he must have met the old man when he returned from Chacewater, and at that time have committed the murder; and then he must have resorted to various contrivances for the purpose of concealment. But you see, it is by chance that the mother sent him back, in the manner the learned counsel has placed before you, and it was by chance that the old man went to Chacewater, because it was at first thought that the errand might have been done by Elijah Teague himself. He, however, remained at home and Mr Kendall went to Chacewater, and no preparation seems to have been made for committing the crime. At the same time there is very material evidence to show that the deceased could not have come to his death in the manner Elijah Teague has described and it is for you to consider that, although he did not come to his death by a kick of the mare, whether he could have come to his death by a fall from his horse, and whether that would account for what had occurred. It must be observed that Elijah Teague does not say he saw the kick but that he heard the screaming and noise of the horses, and that he ran and found Mr Kendall lying speechless and insensible. But though it is said he may have fallen from the horse and received his wound, and that that would account for all which has occurred; still, on the other hand, the medical evidence is very strong, and it is for you to say what reliance you can place on it. These are general observations and I will now read over the evidence for in a solemn inquiry of this kind, no time expended can be too long.

The prisoner’s story, if true, showed him to be an innocent person, but it is for you, the jury, to consider how fair he was contradicted, and whether those contradictions show him to be guilty.

The plan by Mr Whitley shows the situation of the premises of Deerpark, and of the locality generally.

It seems very extraordinary that Elijah Teague should have prevented his mother from going into the parlour to see her husband, for supposing an accident had happened to him, one would have thought that ElijahTeague would immediately have run to fetch her, instead of preventing her from seeing him when she came to the house. The prisoner’s statement, however, was corroborated by Mrs Kendall, and substantially also by the little girl, for she said she went to the house and left without seeing Mr Kendall.

There was suspicion at one time that Mrs Kendall was in complicity with her son but there was nothing in the evidence to support that view; she did not appear to have had any quarrel with her husband, she had no revenge to gratify, and nothing to gain by his death.

The prisoner’s next statement was that he remained in the house an hour or more after his mother had left. This does seem strange, that he should have remained so long in the house, and should not have gone to call some neighbour. It is, however, for you to consider what you think he might have been doing during that time. As for the key not being over the stable door, I do not think that circumstance would amount to much, because in the flurry Elijah Teague was in at the time, he might not have known whether be put the key in his pocket, or over the door.

It was, however, very strange that he headed for Truro to fetch a medical man, instead of to Chacewater in the first instance, that being so much nearer than Truro, and that after he had proceeded some way towards Truro, he thought he might get a doctor from Chacewater sooner, and then have turned back. Why did he not make that decision before?

Mr Carlyon gave his statements very clearly and fairly. His opinion was, and though he is no medical man, it was a point on which any man might form an opinion. He said he thought from the appearances that the hammer was the instrument which produced the man’s death.

Mrs Kendall, the prisoner’s mother, no doubt had a strong leaning in favour of her child, and her evidence was to be received with caution but her statements were not contradicted and according to her, there was no lying-in wait until the old Kendall returned from Chacewater, for it appears that her son Elijah was at first accompanying her to Grose’s, where he was to sleep for the night.

It does seem strange that Mrs Kendall did not insist on going into the parlour to see her husband. According to her statement, however, Elijah said, “You must not go away, you must stay here, or go for a doctor”. Now, if he had gone and she had remained, it would have given her ample opportunity to see what had been done and that is a circumstance for the consideration of the jury.

Another of the extraordinary incidents of the case was the conduct of the Groses and the Sandoes when they came to the house, that they should not even have opened the window, when they had reason to suppose there was a man inside who might be in the agonies of death.

The next witness was the little girl Dunstan [Mary Kendall’s granddaughter], whom I thought it important to examine to get at the truth. From her answers, it is clear that when she was at the house with Mrs Kendall, the body of Mr Kendall was in the parlour, and Mrs Kendall and the little girl were prevented by Elijah Teague from seeing him.

Another witness, Mary Grose, spoke of their fancying they saw a light in the kitchen as they were approaching the house, but I think that was a circumstance to which you can attach no weight.

Henry Grose spoke of Teague having put the deceased’s feet in warm water, which seemed a strange thing to do after the man was dead, yet it might have been done without anything wrong about it, for Teague said he put his feet in water because the doctor told him to do so. The doctor says he gave him no such directions; but it was said by prisoner’s counsel, he either may have forgotten it, or the prisoner may have thought he gave that direction. It was not a material circumstance. It seemed somewhat strange, also, that after the dead man’s shoes were taken off, they were put on again.

William Sandoe speaks of his looking into the parlour with a lantern between nine and ten o’clock on the night the old man came to his death. That he could see into the room, as he states, was confirmed by an experiment by two constables on the 29th of July. He says there was no body in the room when he looked in and that if there had been, then he must have seen it. The inference which you are called on by the prosecution to draw from this is that the prisoner’s statement is not the truth, and that something was being done with the body at this time and that it was afterwards brought into the parlour.

As to the evidence of Jane Hobbs, whom the prisoner overtook on her way to Truro, it did not show that the prisoner’s story of what took place was incorrect, for it appeared she was so frightened she did not know what he said to her.

Then, there was the evidence of that very important witness, Mr Moyle, of Chacewater. It appears Teague told Mr Moyle that Mr Kendall had been stunned, and had a slight cut in his forehead. This was strange, especially as he afterwards asked Mr Moyle, if the old mare would be knocked in the head if Mr Kendall died.

Mr Moyle speaks of the spots of blood in the lane. The prosecution suggests that Elijah Teague put the blood there for the purpose of concealing his crime. On the other hand, it is said that the spots came from the deceased when he fell in the lane. The surgeon’s opinion was that the blood had been placed there when it was nearly cold and coagulated. I thought at first that the surgeon had put his knife into this spot of clotted blood, and that then it had come up in a clot, and left no soil underneath; but it appears, on inquiry, that he put his knife under the spot horizontally and had taken it up. As to the effect of this test, you can form an opinion as well as a medical man, and it is for you to consider whether the blood was in a fluid state when it was first on the ground. If the prisoner put the blood there, it must have been after his mother left the premises, and before he went to Truro and back to Chacewater; he says he remained in the house an hour or more; how he employed himself during that time, we do not know.

The surgeon further says that on the Tuesday he observed spots of blood mixed with water on the kitchen wall, and there were some spots of pure blood on the kitchen table. This was very curious but the surgeon remarked that it was impossible to say whether or not it may have been the blood of some other animal.

The surgeon also states that there were furze prickles on the old man’s coat and it must be observed that the one witness said there was some furze on the side of the road, between where the prisoner says he found the body, and the old man’s house.

The surgeon states his belief that the wound in the deceased’s forehead could not have been produced by a fall. That, I think, must depend very much on the momentum with which a person falls to the ground. In the case of a person coming down with velocity, a stone on which the body fell has produced very great results, and may produce effects on the skull as well as a blow from an instrument in the hand. But on that matter, gentlemen, you are to form a judgment as well as the doctor; there is no doubt he is a witness quite sincere, and his evidence is for you to consider.

As to another point, the Counsel for the defence seems to have been misinformed, for there is not the slightest foundation for thinking that the surgeon has tampered with any of the witnesses.

Edward Michell is a very important witness. If his conversation with Teague about the amount of blood did take place then it most materially contradicts the story Elijah Teague has told, and it might lead to an unfavourable inference. It would tend to show that Teague had been dabbling with the blood and would lead to the consideration whether he had not taken some and put it where he said the body was at first discovered by him. Still, it is strange that this conversation should have taken place between them when he had said nothing of the sort to any other person. Michell asserts that there was no enmity between him and the prisoner but the manner of the witness was so unsatisfactory, that it is for you to consider what reliance you can place on his statement of this conversation.

Nancy Michell seems a very decent young woman and her evidence stated nothing unfavourable to the prisoner, for what he said to her was not at variance with what he said on other occasions.

There was also the evidence of finding the deceased’s hat in the lane – between ten and eleven o’clock on the night he came to his death. If that was the hat of the deceased, which it seems to have been, and it was found there without the prisoner having put it there, it would be a strong confirmation of his story; for it might naturally be supposed, that whether the deceased had fallen from a horse, or received a kick in the way described, his hat would be found nearly at the spot. But it is possible that if Elijah Teague put the spots of blood there, that he also put the hat there for the purpose of deceiving the world and concealing his crime. But there is no proof that he put it there, and it is for you to say, if you can, from other circumstances, safely infer whether he did or not. It is for you alone to come to a conclusion on that subject.