“Near nuff won’t do, it gotta be zact.”

“Tis zact”

“Well, tha’s near nuff then!”

Troora Boy, Alan Murton has been at the keyboard again and this time he’s sharing with us his likes and dislikes of Cornish humour. A timeless viewpoint, supported by listening to a Friday night banter in many a Cornish pub.

I’m a Dreckly specialist and wait for a deadline to get perilously close before tackling any job. My procrastination has given me opportunity in this essay to pay tribute to Lilla Miller, aka Mrs Rosewarne, who died a while back. She was a modern standard bearer for all that is best in Cornish humour and was much loved by the Cornish people who enjoyed her comedy. I saw her live just once but instantly identified with her alter ego and remember many contemporaries of my late mother who could have been her role models.

A television programme on our screens back in the early noughties was Wild West: it did little to upset me as a Cornishman but was short of good writing and perception in characterisation – it therefore offended me as a writer and lover of comedy. A shame that the BBC could not have had the consultancy services of Lilla Miller to breathe Cornish spirit into the pasteboard characters, and richness into the dialogue – the programme may then have lived up to the splendour of the scenery.

Can you remember the full eclipse of the sun? I do because I was among the lucky ones who enjoyed the sight of the clouds parting a few minutes before totality. Next morning I met a friend outside the local shop and we passed the time of day in our best Troora Boy accents…

“See the ‘clipse yessday did ‘ee Derek?”

“No boy but I lissunned to un on the wireless!”

Cornish humour exemplified by the sharp wit and classic debunking of what had been almost a national disaster.

I am often asked to define the essence of Cornish Culture and reply: “Community”. This must also be the basis of any definition of Cornish Humour. It is now, as always, based on the ties that bind us, sometimes it is a defence against threatened violation of our Cornishness. Any region of the United Kingdom that has our strong sense of community may claim a distinctiveness for its humour and I once shared an entertainment evening with a Geordie friend – my Cornish tales and his, based on the Jarrow march – the decline of the shipbuilding industry and their remoteness from London.

A sense of humour and the ability to laugh are two of the essentials that define our humanity. Academics will pontificate that very few comic situations underpin all our stories and jokes but humour defies analysis and it is often sheer spontaneity that makes us laugh. I will always regret not having a tape recorder when two of my uncles kept the family in stitches on the evening after my niece’s wedding. They’d once been a concert party double act but this was unscripted, and unrehearsed. Their stories owed much to their working life together as painters and decorators. Every word claimed as fact and validated: “You’ll bear me out Frank…”

I use some of the tales I can still remember and one favourite is when Ken, as an apprentice sent to Mousehole, was billeted with a fisherman’s wife.

“I got there Sunday and had fish pie for me tea. Monday ‘twas fried herring, Tuesday I had steamed cod and Wednesday I came home to a whole mackerel. Thursday morning I came down and found the landlady maized as a brush with the fire.

‘Look at it,’ she said, ‘bugger’ll only burn one side, that means there’s a stranger comin’.

‘Hope ’tis the butcher!’ I said.”

No essay on Cornish humour would be complete without mention of Jethro – famous for bringing laughter to thousands. I must declare an attitude before continuing. I believe that true humour creates laughter without causing offence. You will understand then that I respected Jethro as a very funny man and his ability to make audiences laugh was enhanced by his appearance, his rich voice and accent. He was supreme when he stuck to material based on his roots, free from unnecessary strong language. The principles of marketing apply to humour and the target audience has to be considered, Lilla Miller, gentle lady, was at home in the chapel and Jethro selected his television material carefully – perhaps I am old-fashioned, but for me that is when he was at his best. The image of Denzil waiting for his business calls at the village ‘phone box brings memories of anxious waits at Truro’s railway station.

Jethro’s story of the famous train That don’t stop Camborne Wednesdays is full of wit to which we can all relate, as is this line in which the busy booking clerk replies to the question:

“How long does the journey take?” with the classic:

“Just a minute…”

“That’s quick…”

There is an apocryphal tale in my family about a teenage aunt out after dark, stopped by Police Constable Moon in Truro’s gas lit streets who, when asked: “Where’s your lights?” replied “Next to me liver…” and pedalled into the darkness.

More examples in vogue in my schooldays were similar one-liners:

Man to booking Clerk: “Two to Looe.”

Response: “Pip Pip!”

My father was ever the optimist: “There’s no bad beer boy – just some’s better than others…” although he also used to say: “Don’t like this beer much – I’ll be glad when I’ve had ‘nuff…” and “They clouds aren’t passing over, they’re going back for refills…”

Denzil Penberthy, Jethro’s creation, is in the tradition and source of much Cornish humour – the local Character. I know that I am not alone in relating the doings of Ned Webber – certainly most Truro boys of my vintage and a bit later recognize him as the butt or personification in a wide range of stories and jokes. He was never a bigger liar than Tom Pepper – kicked out of Hell for lying – however his multi-faceted persona allowed the telling and re-telling of hundreds of favourite stories. The earliest I can remember is about the day he was supposed to help two friends carry a hen house from Hendra to Malpas – he failed to show up and they struggled on without him. When they dropped the coop Ned popped out through the door – he’d been inside carrying the perches.

Many Ned Webber episodes relate to his working life – he had, so the tales would have you believe, more jobs than most. As a railway guard he picked up a train at Plymouth and duly signed the work sheet:

“Took over train from guard at Plymouth, One dog in guard’s van. Dog dead.” And later: “Handed over train at Truro. One dog in guard’s van. Dog still dead”.

Not the funniest story ever told but enhanced by its association with Ned Webber, the character we all knew and loved. Here’s another example. It seems that Ned had been working steadily at a labouring job in Truro and was happy until his boss called him in one day:

“Ned, the job here’s good as done – you got to go to Camborne to work from Monday”.

“Boss don’t ee send me to Camborne, they’m all street girls and rugby players down there.”

“Steady Ned, my wife comes from Camborne…”

“What possishun did she play sir?” As ever too late – damage was done!

In the queue at the railway station he heard the lady in front say: “Two for Mary Tavey”.

She paid her money, picked up her change. Our hero moved forward: “One for Ned Webber please…what do ‘ee mean where’m I going to, you didn’t ask Mary that…”

I have already laid down the hypothesis that Cornish humour is vested in our community chains and sometimes in community conflicts – church and chapel, town dweller and country boy and, of course, native bred and visitors. In addition we do not tolerate fools gladly and another essential in our humour is the pricking of inflated egos.

One conflict with which every Cornishman can identify is the Camborne/Redruth rivalry fought out on the rugby field. I went to a Boxing Day match once and applauded a Camborne try. A few minutes later I was clapping a Redruth penalty. The man next to me had had enough: “Come from ‘Druth do’ee?”

“No…”

“Camborne man then?”

“No…”

“Then hush up! ‘Tis none of your bleddy business!”

My favourite story with a religious connotation is of the lifelong fervent Methodist, an old-fashioned Wesleyan who’d have no truck with They Anglicans. Told that he had but a few hours to live he asked his shocked family for the Vicar.

“What are ee saying Albert? You’m a good Methodist and always have been?”

“Well boy ‘tis simple ‘nuff. If I gotta go, I’d rather it was one of they than one of we…”

Where was your ecumenical theory in those days?

Whole communities have been tagged for a legendary gaffe, an example is Chacewater – forever known in my family as Chacewater Scat-ups and taitty fields. The Scat-ups allegedly dates back to a volunteer unit in the army in the First World War who didn’t acknowledge the Regimental Sergeant Major’s order: “Squad dismiss!” – fortunately someone was able to translate and they fell out to the familiar: “Scat Up!”

I’m told that it’s not Politically Correct to talk of emmets and foreigners. A confession then – PC makes my hair stand on end. I’m not an isolationist and the first to acknowledge the need for our tourist trade to flourish and the contribution that many have made who were smart and lucky enough to come to work in Cornwall. However, that doesn’t stop me including in my repertoire the comparison of emmets to haemorrhoids – those that come down and go back are not too bad but those that come down and stay down are a real pain in the ass. I recognized the potential problems for a repatriating Cornishman, my credibility likely to be questioned: “There’s that Alan Murton with his up-country ideas.”

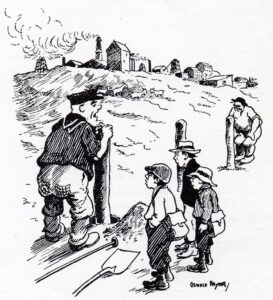

A classic in the pricking of inflated egos in furriners, told in many ways, is the Cornishman leaning over a gate when a smart car pulls up, the visitor winds down the window and asks the way. After a protracted conversation – which gets him nowhere – the frustrated visitor asks:

“Don’t you know anything?”

“Ess cap’n – I knaw I arn’t lost.”

In an alternate version the exchange goes like this: “Which is the quickest way to St Ives?”

“Are ‘ee walking or driving?”

“Driving.”

“That’s definitely the quickest…”

I mustn’t forget the ultimate: “If I was you, I wouldn’t start from here.”

Sometimes the best humour is generated unconsciously. My father was a linotype operator in the West Briton and took it as a failure if his work came back with corrections from the proof reader and a disaster if any escaped into the paper but he enjoyed the farmer whose horse was advertised with a lamp (limp) hind leg and rang to say that it met blackout specifications. Another who said he would employ the shorthand (shorthorn) bull if it could type. Computer spellcheckers, which miss so many errors, wouldn’t have picked up either of those classics.

In the 1950s, Troora Boy was a frequent letter writer to the West Briton and was given column space in the Monday Edition. A local businessman, the late Len Carveth, was the author of these pieces, which were always amusing and topical. I remember with affection his letter about the passing of the Iron Duke. Not Lord Wellington but the men’s urinal situated at the end of the Leats. It was built of cast iron with a tracery pattern, occasionally painted (more often rusty) and much used by locals whose business took them to High Cross. The vandalism of the council in scrapping an architectural wonder and a comfort to generations of Truronians, attracted his sparkling wit. I wonder if the editor would afford so much space to a local humourist today?

The Iron Duke reminds me that it was not unusual to see a poignant notice in the Gents in pubs: We aim to please. You aim too please! In a pub car park I have also seen the request: Please Park Pretty. Not everybody is amused by the wag in Pool Market who advertised his services with: Ears pierced while you wait, but it makes me grin.

No essay on Cornish humour would be complete without reference to and examples of the rich fund of stories about our national dish, the pasty. Continuing the theme of pub notices leads to the London pub in Praed Street advertising Special Offer – A pint of best bitter, a woman and a Cornish Pasty – just £5. Fresh off the train at Paddington, Ned Webber (who else), went inside.

“Would you like the special offer sir? It’s Real Ale and the girl is a corker…”

“That’s all very well but who made the bleddy pasty?”

The biggest challenge for a young Cornish bride is to make a pasty that comes close to those her mother-in-law made. Mary spent an anxious hour waiting for her husband who disliked swede in his pasty. She took the pasties from the oven and was upstairs when he came through the door. “I’m home maid, pasties are smelling good…which one’s mine?”

“Can’t ‘ee see – I’ve marked them.”

“But they’m both marked TT…”

“Right ‘nuff – one’s ‘Tis turnip – the other’s Tiddn’ turnip.”

Home from South Crofty a young husband looked at his anxious wife and before she could ask said: “Tasted all right, what I could salvage – pastry was too good and it fell abroad before croust – mother now, she could heave hers down to us…”

The biggest joke of all is asking a Cornishman to keep it brief but there ‘tis. In summary I submit again that our humour belongs to the communities and characters that generate it. I hope that there will be more Lilla Millers and Jethros to perpetuate our dialect without which much of our humour becomes bland. I hope my piece has provided some amusement without offence. I feel like the husband of the Cornish lady, who was invited to talk to the local Women’s Institute on Growing. His anxious wife met a friend who’d been at the meeting and asked how he’d done.

“Alright really but he would keep using the word dung. ‘Twas cow dung for this, horse dung for that…”

“My dear maid don’t ‘ee complain about that – took me thirty years to get him to say dung…”

Truro born and educated Alan Murton returned to Cornwall in 1994 with Writing as a key aim in early retirement after a course with Open College of the Arts with Cornish poet Philip Gross as his mentor. He sent some of his writing to Cornwall Today and was soon a regular in its pages until the West Briton took it over. He joined Truro Creative Writers in 1995 and worked with them, for 20 years as Chairman/Secretary.

Apart from competing in Old Cornwall Society competitions he wrote for two subscription magazines and has been published nationally as well as locally.

‘hansom article form Alan – reminds me of my Dad – especially Ned Webber!