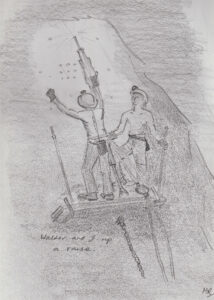

(Sketch: Mike Ricks)

(Sketch: Mike Ricks)

Mike Ricks brings us his evocative story of the time when he was a Cornish miner. Reading this leaves you in no doubt about the harsh conditions underground and perhaps goes some way to helping us understand the extraordinary camaraderie developed by those who laboured there.

The contrast couldn’t be greater. Two weeks out of the Royal Navy and I found myself many fathoms down, working in a Cornish tin mine. You don’t forget the first descent. Crammed into the cage with a dozen ruffians dressed in rags, we dropped into the pit of hell – namely Cooks Kitchen shaft, the aptly named upcast shaft, into the hot, humid, dripping darkness. A few cap lamps were lit revealing unshaven faces inches from mine, the odd joke, but mostly silent, another day’s work.

I spent much of the first day hanging a screaming compressed air-driven fan and PVC ducting into a development end (a tunnel six feet square in section) and you didn’t get a ventilation fan until things were unbearable. We were all, including the driller at the face with his roaring jackleg drill, stripped to the waist in a lather of sweat. At least he was breathing the exhaust from his drill.

The second week, now working at Robinson’s shaft side, the downcast shaft, I was sent in to work with a raise miner. There are few jobs more arduous, dangerous, noisy and exhausting. After walking about a mile along deserted tunnels we had a quick cup of coffee at the croust seat and started scrambling up and down the steeply inclined tunnel, grabbing one-handed at the chain, our boots struggling for grip. Up with two planks, two steel pins, the rock drill, air and water hoses, drill steels, wash down, bar down any loose rock, and then we proceeded to drill standing on the planks for hours under a stream of water and grit, all to the roar of an Atlas Copco Puma. I squelched my way back to the shaft station for a box of gelignite and we loaded the explosives and electric detonators, ran out the wires and retreated after bringing all the gear down. There was a terrific crump as our day’s work was blown to rubble, and we ran for the cage. No time for a lunch break. And that day after day, no earmuffs, no safety glasses, no harnesses, you just did not fall.

Working with a machine man, drilling and blasting, meant extra money, splitting his contract 60/40. I worked with many of them as a reliable and willing helper, with the calm ones, the cranky ones, the cheerful ones and the grumpy, in raises, drifts, stopes, box holes and inters, all the jargon of Cornish shrinkage stoping in the granite / killas contact under Carn Brea. The ore, cassiterite, was being mined from steeply dipping lodes from the 210-fathom level down to 340 fathoms back in 1970.

When I wasn’t doing that, I would be with a small gang of day labourers, often pushing ore wagon bogies, loaded with rails, sleepers, timber and materials for miles along old tracks in deserted tunnels which ranged far and wide under the environs of Redruth, Camborne and Pool, to areas with the names of the surface above, Tin Croft, Dolcoath, Roskear. Sometimes we pulled old rails out of hot dry old tunnels or more often, lay track and sleepers right behind a drift miner, digging the sleepers down half underwater, gasping for air in the heat as he drilled, pounding in the dog spikes with the back of a pick.

Croust time was half an hour, sitting on planks with a back rest, eating a sandwich, with weak thermos coffee, and a bit of a laugh delivered with that Camborne accent. Many of the older machine men were Poles, who remained after the war and married locally. Some were Sicilian, especially the trammers who collected the one ton mine wagons when they were filled from the chutes that drew ore down for the stopes, shunting trains of them back to the ore pass or shaft with small electric locos. At times, when my mate was mucking out with an Eimco 12 B rocker shovel, another noisy air driven bit of gear, slamming it back and forth into the muck pile, I’d be there to push the full wagons out to the cross cut and bring in an empty. And there was the time we had to put in a switch in the rail track and we had to fill the wagons by hand with a short-handled shovel until we were three rounds in and could lay track. We took turns, collapsing while the mate took the next wagon.

You could sum up the whole business with words like sweat, noise, heat, humour, tempers, frustration, and a few moments of silent fear going back in to check a round that hadn’t exploded. But above all there was the camaraderie, or mateship, of men working under hard conditions, relying on each other, akin to soldiers at war.

I left for Canada after working there on and off until 1975. I lifeguarded in the summer, lucky that the mine captain was also captain of Porthtowan Surf Club and would take me back each year when the shadows fell across Chapel Porth Beach. On rare visits home to Cornwall I could not drive through Pool and see the wheels on the headframe spinning without thinking of those down there in the roaring gloom of the Cornish granite. It was near the end of a remarkable era.

Mike Ricks

Mike Ricks

I was born and grew up in St Agnes. From Truro School I served in the Royal Navy before a career change into mining. I graduated from Camborne School of Mines in 1974 and worked in Northern Canada for six years before emigrating again to Australia where I am now retired in SE Queensland.

An eye-opener, Mike. Thanks for this account. Underground mining was never an easy option, even in the 1970s.

Very interesting and quite shocking – Cornish mining is thought of in a romantic way even after being told what the conditions were like working underground 100s of years ago – but this was the 1970s!

Yes,a pretty comprehensive account of working underground. I was working there at a similar time. The consolation for the working conditions was the pay packet,usually double what you could earn on surface.I left to become a teacher and have good memories of my time at Crofty.