Another article by Alan Murton, master wordsmith, who never fails to paint a picture of his beloved Truro. This one, about Richmond Hill, is truly evocative and full of nostalgia.

I was born on a hill – not surprising in Truro really, not just any old hill though – it was Richmond Hill where everything of importance to the community seemed to pass by. It’s still there – but I wonder does it still reflect the social history of today as it did in my memories of times gone by? The hill is just a hundred yards down from the railway station and from what used to be the busiest marshalling yards southwest of Plymouth’s Laira sheds – well within the rattle of shunted wagons and the whistle of the Riviera announcing its daily arrival.

Home was one of the sandstone, terraced houses that opened out on to tiny front gardens on the south side. The gate and the spiked iron railings vanished in the 40s – cut off by the blowtorch to make munitions for the war effort. Cement block walls have replaced most of the railings – just as the sandstone fronts of the cottages have been clothed in a variety of weatherproof coats to keep out the rain and damp. The cottages on the opposite side had scrubbed doorsteps that came straight down on to the granite slabs of the pavement.

I can remember three shops, the one next door supplied paraffin oil for heaters and lamps (hand pumped into a brass measuring jug from a shiny tank that stood in the shop) as well as wax candles, kindling, fire lighters and soap flakes weighed out to order, it had an unforgettable smell all of its own.

A few yards down from Richmond Terrace was the grocery, newsagent and tobacconist’s shop run by a lady who served the people of the area well for a lifetime. Miss Pickford’s customers’ loyalty helped her survive the arrival of supermarkets. The third shop at the bottom of the hill changed hands and trades many times but I last remember it as a barber’s.

(Photo: Argall)

(Photo: Argall)

Richmond Terrace runs north off the hill, almost to the railway line and the viaduct and I remember it best for the field that it over-looked. It was easy enough to squeeze through bow-shaped gaps in the iron railing and “sling” the ten or twelve feet into the field below. That field was Wembley Stadium, Lords Cricket Ground and most of the battlefields of the 39/45 war to my generation – not to mention the set for the “re-make” of every swashbuckling film Errol Flynn ever made. Its real purpose was to pasture the horse that George Venn drove to deliver milk from his float to those customers who didn’t collect from his dairy and green-grocery shop in Frances Street. As children we were never refused a ride on the cart and would stand on the platform while he measured the milk into jugs that would soon be covered in beaded muslin and placed in the meat safe on the back kitchen wall. His dairy was where I bought my first “proper” Cornish ice cream after the war.

Next door to us lived a gentle man whose job came second only to engine driver as a childhood dream. He drove for the GWR, one of the massive shire horses that pulled the carts distributing freight around the city. Their drivers reined them back and their hooves struck sparks as they took their loads down the steep hill and, straining against the collar, they returned empty in the late afternoon.

Richmond Opening, now up-graded to Richmond Place, was a safe haven off the hill for many of our games – hopscotch, giant strides and “tin-can-tommy,” the game one of the evacuee families brought with them. The two round granite posts beside the pump that kept cars at bay were a natural height for leapfrog, their tops worn smooth by the hands of generations of local vaulters.

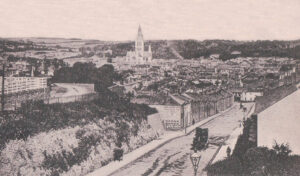

The hill runs almost due east/west and when I stood by the gate on a summer evening I could look east and pick out all the landmarks in the city below. Shops and offices clustered around the cathedral, its three spires glowing with the warmth of the sun. The spires were like antennae that directed the congregation’s prayers up to heaven while the fourth, shorter spire has always been tiled in copper and jarred a luminous green. Just beyond and to the right stood the town clock, square, solid, defying time its large white face, black Roman numerals and massive hands visible from a mile away. The clock sported a golden weathervane that locked to the wet south-westerly prevailing wind. Well beyond and high on the hill across the town the sunlight reflected in the windows of Truro School where the grey dormer-windowed front faced the setting sun and was buttressed at one end by the chapel which is no doubt still slipping in inches down towards the river.

The hill was a historical news bulletin. A camcorder or ciné camera left running, with an infinite supply of film, would provide images of a substantial part of the 20th century. Not now perhaps, the decline of the railways, the construction of dual carriageway bypasses and the proliferation of motorcars has robbed the hill of much of its passing pageant.

Some of my boyhood images haunt me. For example, I can still see the sad crocodile of young children straggling down the hill from the railway station, frightened hand clasped frightened hand as groups of London’s East End evacuees walked the last few hundred yards to St George’s Church Hall, where nervous volunteer foster parents waited to collect them. The war had come to Cornwall. It was in the sad eyes of those disoriented children sent into exile away from the Blitz. It was in the labels pinned to their clothes. It was in the gas masks hung on string around their necks in square brown cardboard boxes.

The first GI’s that came to the county swaggered down from their tented camp on the golf course at Treliske in their tailored dress uniforms. Small boys and girls harassed the soldiers as they went seeking pleasure in the town pubs with cries of “Got any gum chum?” The Exeter Inn only a few yards further down the hill was an early port of call – it became the Admiral Boscawen and now a private home. Proud Gurkhas in shorts and puttees, bayonets still in the scabbards fixed on their rifles, marched up the hill after one of the many fund-raising, jingoistic parades over the granite sets of the main streets of the city.

There are peacetime images too, Bertram Mills’ great circus came to the station and elephants – trunk to tail – led the publicity parade that went down the hill and through the town to the Big Top erected on the Truro City football ground at Treyew Road, ready and waiting for the first performance to a full house. Caged lions and tigers drawn by huge tractors, clowns in full make-up, scantily clad girls astride prancing horses followed behind and high on a flat truck sat an Oriental lady dressed in transparent harem trousers and skimpy top – she cuddled the crocodile that she purported to hypnotise twice nightly.

Whatever the passing pageant, front doors opened and people crowded the pavements to watch it pass by, it is hard to believe today how many people turned out on an evening in 1946. In the siding above the Terrace a goods train unloaded its wagons on to the slat-sided Fyffe’s lorries that carried their ripening green loads to their depot. Straw blown from the lorries littered the streets for days. Who cared! The banana was back, the war was over and the good times were returning.

My generation of children were lucky to be pupils at Bosvigo School, just round the corner. The Headmaster, Mr L Treloar, was an inspiring and dedicated teacher who set many of us on our way with scholarships to Truro School, the Girls’ High School, and the County Grammar Schools. He sent many more out into the world to be good citizens and loyal employees.

The school and the hill played a big part in shaping my life as I’m sure it did for many of my contemporaries, an Anglican canon, a Cornish bard, a university professor, a television newsman, a councillor or two and, from just round the corner, a Cornwall rugby player – I might just have swapped with him.

Truro born and educated Alan Murton returned to Cornwall in 1994 with Writing as a key aim in early retirement after a course with Open College of the Arts with Cornish poet Philip Gross as his mentor. He sent some of his writing to Cornwall Today and was soon a regular in its pages until the West Briton took it over. He joined Truro Creative Writers in 1995 and worked with them, for 20 years as Chairman/Secretary.

Apart from competing in Old Cornwall Society competitions he wrote for two subscription magazines and has been published nationally as well as locally.

Alan’s ‘stories’ always paints pictures in my mind. I can ‘see’ the crocodile of evacuees trundling down Richmond Hill and the American soldiers swaggering down to the Exeter Inn —- Thank you Alan

What beautiful memories of living and growing up in Truro, throughout out the war years, and the arrival of the American soldiers , from Treliske , marching down through the town, showing off there smart tailored uniforms, and their 1/2 track vehicles and personnel carriers,

Remember standing in front of what Truro Rural District Council offices. To watch the American troops Parade down through the town ,and back through Victoria Square Kenwyn Steet,Little Castle Street,back to encampments.

I know of the crane coming off its low loader and stopping in the wall of 14 Ferris Town, don’t recall the Gurkhas being down here , but thanks to Allan Murton for this very interesting piece of Cornish

My father and his parents grew up there ( No 8 Richmond Hill ). I lived with my parents on the right hand side going down the hill ( 2 Alexander Terrace). My father and I both went to Bosvigo school.

This was a fascinating read, thank you so much.

***My grandparents lived at No 31 (not 8)!

Three doors down from the top of the hill! Neighbors of the Eva family.

Miss Bray a teacher at Bosvigo lived in number three

My great grand aunt Elizabeth Ann Cook lived at 79 Richmond Hill Í dont believe this number exists anymore