I do swear, that I have not received or had by myself, or any person whatsoever, in trust for me, or for my use or benefit, directly or indirectly, any sum or sums of money, office, place, or employment, gift, or reward, or any promise or security, for any money, office, employment, or gift, in order to give my vote at this election; and that I have not been before polled at this election. So help me God.

I do swear, that I have not received or had by myself, or any person whatsoever, in trust for me, or for my use or benefit, directly or indirectly, any sum or sums of money, office, place, or employment, gift, or reward, or any promise or security, for any money, office, employment, or gift, in order to give my vote at this election; and that I have not been before polled at this election. So help me God.

~ The Bribery Oath. The 1729 Bribery Act was introduced to address corruption in elections[1]

Everybody comes out ahead.

~ Joseph Heller, Catch-22, 1962, p248

[1] Quoted from: https://ecppec.ncl.ac.uk/features/bribery/

Ancient Seal of the Borough of Grampound[2]

The 1818 General Election saw many electoral campaigns champion the burning issues of the day, such as parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation. Future giants of Victorian politics won seats in the Commons, such as the Whig Lord John Russell, and Tory Robert Peel[3].

No such grandiose policies or political heavyweights were on display in Grampound, however. But that in no way meant its hustings were tamely played out. Quite the contrary.

The 1818 election in Grampound uncovered a scandal so immense the village was stripped of privileges it had enjoyed (and exploited) since Tudor times. The antics of the characters involved in this scandal set the wheels in motion for the Great Reform Act of 1832, itself the bedrock of modern parliamentary democracy[4].

In 1818 Grampound’s population was similar to what it is today, around 6-700, and great were the levels of unemployment and distress in the village[5]. Poor in Georgian times it may have been, but Grampound had once been an important town in medieval Cornwall. During the reign of the Boy King, Edward VI (1547-1553), Grampound was made a Borough constituency, commanding two seats in Parliament[6].

By the 1800s, however, and probably long before, Grampound’s star had fallen significantly, and it was judged by many reformers to be a ‘Rotten Borough’. These were settlements with a poor, tiny electorate that nevertheless returned Members to Parliament, and were obvious targets for exploitation and bribery.

Those readers who recall the episode of Blackadder The Third will be aware that a Rotten Borough was a

…tuppenny-ha’penny place…Half an acre of sodden Marshland…Population: three rather mangy cows, a dachsund named Colin, and a small hen, in its late forties…

~ Rowan Atkinson as Edmund Blackadder, Dish and Dishonesty, BBC, 1987

Comic maybe, but the description is actually not far from the truth. The most notorious Rotten Borough was Old Sarum, in Wiltshire. In the 1800s it still returned two MPs, even though nobody actually lived there[7].

Hot on Old Sarum’s heels in the notoriety stakes was Grampound. Of its population of 700 in 1818, only sixty men (and only men) were allowed to vote, and they were judged the lowest on the franchise rung. When an interested party made enquiries as to the number and calibre of Grampound’s electorate, the answer was

Pot-wallop…

~ Royal Cornwall Gazette, July 24 1819, p4

A Potwalloper was the pejorative term for the male head of any household with a hearth large enough to boil a cauldron. This qualified him to vote[8]. Potwallopers, the lowliest form of voter, were known to be targets for bribery in pre-reform Britain:

The more enlarged the suffrage, the more unassailable is the constituency by corruption and bribery; while the narrower, the more is it open to that influence.

~ Leeds Times, editorial on Potwallopers, March 16 1839, p4

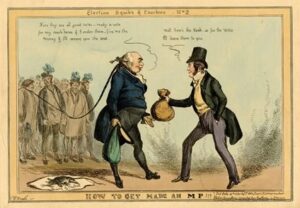

The smaller the electorate, the easier to control by money. But, as the illustration below makes clear, the Potwallopers were all too aware of their worth in the election market:

A Potwalloper, by Robert Seymour, Times, July 12 1830. The gentleman on the left exhorts him to use his vote for the common good; on the right he is offered ‘something for his pot’ in return for his loyalty. The Potwalloper slyly rubs his hands with glee.

A Potwalloper, by Robert Seymour, Times, July 12 1830. The gentleman on the left exhorts him to use his vote for the common good; on the right he is offered ‘something for his pot’ in return for his loyalty. The Potwalloper slyly rubs his hands with glee.

Indeed, considering Grampound, it has been noted that the

voters…far from being controlled by the patron, could themselves control him. They supported him only while he satisfied their financial requirements…

~ R. C. Jasper, “Edward Eliot and the Acquisition of Grampound”, English Historical Review, 58:2 (1943), p475

As we shall see, the 1818 election at Grampound was not to be decided by the most forceful personality or the most crucial issues; what would swing the day boiled down to who had the most capacious wallet.

Tomb of Sir Christopher Hawkins (1758-1829) at Probus Church[9]

Tomb of Sir Christopher Hawkins (1758-1829) at Probus Church[9]

Sir Manasseh Masseh Lopes (1755-1831), c1825[10]

Sir Manasseh Masseh Lopes (1755-1831), c1825[10]

In Georgian times, Boroughmongers were well-heeled gentlemen of dubious morals, who looked to exert their power and influence through the buying and selling of Rotten Boroughs. Often MPs themselves, they set up ‘patrons’ (front men) in other constituencies by purchasing enough votes for them to ensure a majority.

Two of the worst, especially in Cornwall, were Sir Christopher Hawkins and Sir Manasseh Masseh Lopes. They were certainly recalled as men who

…corrupted constituencies.

~ Cornishman, May 5 1889, p6

Though today Hawkins’ seat at Trewithen is a popular attraction, and he was an early investor in steam-power, in his lifetime he was infamous. As miserly as he was immoral, he wielded much power in Cornwall. In the 1806 Election, MPs at Grampound, Helston, St Ives, Mitchell and Penryn were all in his pocket.

His main Cornish competitor in these years was Sir Francis Basset, 1st Baron de Dunstanville, against whom Hawkins publicly issued a vendetta. The two men fought a duel in London in 1810, each getting two rounds off at the other before sanity prevailed[11].

Lopes had been born a Jew in Jamaica, inheriting a family fortune made from sugar and slavery. He emigrated to England, converted to Christianity (at the time, Jews were barred from Parliament), and bought a pile in Devon – Maristow House[12].

From here, he greased his way into power, becoming High Sheriff of Devon in 1810. By 1818, he was an MP, and had already bought (and sold, at a profit) several Rotten Boroughs. But it seems that those at the very top never forgot his Judaism, or that he was a nabob.

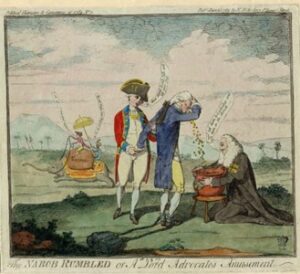

The Nabob Rumbled, by James Gillray, 1783. A nabob was a man who had made his fortune overseas, often by dubious means. Here the nabob spews sovereigns into the hat of a government minister to avoid arrest. Copyright National Portrait Gallery

The Nabob Rumbled, by James Gillray, 1783. A nabob was a man who had made his fortune overseas, often by dubious means. Here the nabob spews sovereigns into the hat of a government minister to avoid arrest. Copyright National Portrait Gallery

The two Boroughmongers lined up over Grampound in 1818[13].

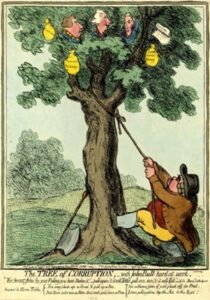

John Bull pulling down the Tree of Corruption, by James Gillray, 1796. Copyright The British Museum

John Bull pulling down the Tree of Corruption, by James Gillray, 1796. Copyright The British Museum

The General Election of 1812 returned the following MPs for Grampound: John Teed (1770-1837), a merchant banker from Plymouth, and Andrew Cochrane-Johnstone (1767-1833), a Scottish soldier[14].

By 1818, Johnstone had already parted company with Grampound, being replaced by Ebenezer John Collett (1755-1833), from Hemel Hempstead[15]. Johnstone had been convicted of fraud in 1814, and whilst in the army had indulged in smuggling, embezzlement, and using his troops as personal servants.

Walter Pomeroy, of St Austell and Johnstone’s election agent, told of how Johnstone in 1807 had donated £200 (over £15K today) to the Grampound Potwallopers, for distribution “among the needy”, and had secured promotion in the Navy for another man of the village[16].

John Edwards, a local solicitor who would canvas for John Teed in 1818, said that Johnstone controlled the Grampound electorate by

…creating terror…

~ Lopes Indictments, p18

He would threaten to get the borough disenfranchised (thus robbing the voters of a valuable source of income) unless he was made an MP[17].

With the by-election of Collett in 1814, Grampound was now firmly in the clutches of Sir Christopher Hawkins: both MPs, Collett and Teed, were his men[18].

Ebenezer Collett, print by William Holl, 1823. Copyright The British Museum

Ebenezer Collett, print by William Holl, 1823. Copyright The British Museum

But the Grampound Potwallopers felt they weren’t getting enough from their MPs. Enough cash, that is. Of Collett it was said that

…he has treated us ill, and we are determined to oppose him.

~ Royal Cornwall Gazette, July 24 1819, p4

While of Teed it was observed that

…we do not think he has money enough to stand the election.

~Royal Cornwall Gazette, July 24 1819, p4

(Which is ironic, when you consider that the term ‘Teeded’ was local parlance in Grampound for taking a bribe[19].)

To this end, in 1815 William Hoare (or Hore), then Mayor of Grampound, travelled to London to find a new source of income. Traditionally in Grampound, the Mayor had a privilege in these matters “beyond the others”, and received £40/annum (just under £15K today),

…for his Kitchen…

~ Lopes Indictments, p16

Hoare visited the Town residence of Masseh Lopes, because he and his fellow electorate wanted

…to be Teeded again.

~ Lopes Indictments, p53

Through the good offices of Lopes’ secretary, George Hunt, 40 men of Grampound’s total electorate of 62 were guaranteed £35 (£2,500 today) each, for voting the way Lopes’ conscience told them. Others received greater sums; Hoare himself received a whopping £306 (£22K). After all, he was Mayor, and had his “Kitchen” to think of[20].

In all, Lopes sunk over £2,000 of his gelt into the pockets of the Grampound Potwallopers. That’s around £145K today.

Hunt instructed Hoare to note the money in his accounts as to be

…applied for public purposes.

~ Lopes Indictments, p27

All above board, you see.

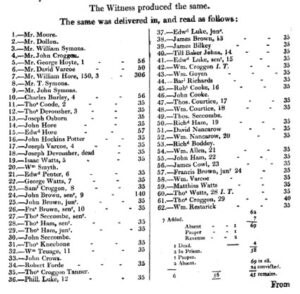

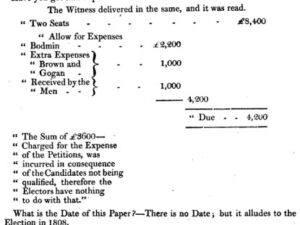

Hunt’s error was to give Hoare a list of moneys paid, and to whom. Here it is:

Lopes Indictments, p30

Hoare’s error was to let this list fall into the hands of John Teed – the very MP he and his fellow Potwallopers wanted out[21].

Lopes’ error was to only bribe enough men to ensure a majority; in any case, he never

…lent any money to a distressed person who had not a vote.

~ Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 27 1819, p4

You have to remember that all

…the Electors of Grampound consider the Sale of their Vote…the great Privilege they possess…

~ Lopes Indictments, p27

In 1817, Teed himself confronted Lopes with the list of names procured from Hoare, and threatened to blow his gaffe. Lopes, expressing surprise at the list’s accuracy, struck a deal with Teed – and, by extension, with Sir Christopher Hawkins[22].

Joseph Childs, an attorney from Liskeard and in the pay of Lopes, would recall that his Master and Hawkins intended to

…unite their interest together…

~ Lopes Indictments, p62

Simply, each would control an MP for Grampound. Hawkins – Teed; Lopes would pick from two Scottish businessmen who resided on Broad Street, London: John Innes (1767-1838), or Alexander Robertson (1779-1856)[23].

Two gentlemen would get an easy ride to Parliament. The Boroughmongers got an MP each. The Potwallopers (most of them) got paid.

Everybody comes out ahead…

Grampound’s Town Hall, where elections were held. In 1818, the ground floor was open and the upstairs supported by four pillars[24]

Grampound’s Town Hall, where elections were held. In 1818, the ground floor was open and the upstairs supported by four pillars[24]

Maybe Hawkins and Teed decided they couldn’t trust Lopes. Maybe Hawkins surmised he could resurrect his own reputation[25], and Teed enhance his, by revealing the level of corruption in Grampound. Both men, and possibly Lopes too, were also aware that the Grampound Potwallopers were not to be trusted either.

Shortly before the 1818 Election, Phillip Luke, Isaac Watts, Samuel Croggan (three voters bought by Lopes), along with John Cooke (who received no bribe) and Nicholas Middlecote of Tregony travelled to London, in search of another Boroughmonger. (Teed’s men rumbled them.) Collett, Teed and therefore Hawkins hadn’t the necessary readies, and nor, in their opinion, did Lopes. His offer of £35 a man wasn’t enough, and in any case not every Potwalloper had been given something for his pot[26].

Indeed, it was later observed that

…the rule of Grampound, if there is a rule, is to get as much as they can…

~ Lopes Indictments, p14

To the Hustings.

Canvassing for Votes, by William Hogarth (1697-1764)

Canvassing for Votes, by William Hogarth (1697-1764)

As the above image suggests, a Georgian election was often a raucous affair. Secret ballots, part of the Chartist campaign of the 1830s, were unheard-of in 1818 and would not become law in the UK until 1872[27]. Previous to this, the voter ‘voted’ by simply standing beside, or proclaiming, his candidate of choice.

The Grampound Election of June 1818 would prove raucous also.

To much “Hissing”[28], John Teed demanded the Bribery Oath be taken by one of the voters, Thomas Devonshire. John Edwards, the attorney from Truro, was in the Town Hall and said that Devonshire

…appeared very much agitated…very pale and trembled…the Book [Bible] appeared as if falling from his Hand…[that]…appeared lifeless…

~ Second Reading, p34

Devonshire had been bought by Lopes for £35 (see the list above); he couldn’t – or wouldn’t – take the Oath without perjuring himself. Furthermore, Edwards had warned him earlier that day that Teed was on the warpath[29].

(In fact, it was commonly known that Teed was preparing indictments; the Grampound Potwallopers were facing jail sentences. In desperation, before Election Day some actually returned their ‘loans’ to Lopes’ secretary, William Hunt. Hunt, naturally, charged 5% on any monies received[30].)

In the hubbub and confusion, another voter, Robert Forde (or Ford) declined to vote and beat a hasty retreat. Clearly, he hadn’t repaid Hunt his £35[31].

Teed, however, couldn’t sustain his demanding of the Oath without having it demanded of him in turn, and perjuring himself also. The Potwallopers knew this[32], and further threatened his agent, Alexander Lambe, with a “pelting” if he persisted[33]. Teed himself was told that

…there would be Murder…

~ Second Reading, p24

if he did not withdraw. Teed, however, had one more ace to play.

And this ace, if he can be described as such, was William Allen, a wool merchant from Truro, who had unexpectedly announced himself as a candidate. Although one of Lopes’ £35 men, he’d been put up (doubtless for a consideration) by John Edwards, Sir Christopher Hawkins and Teed to demand the Bribery Oath. The more Teed could muddy the waters and sow doubt in the Potwallopers’ minds, the more chance Teed had of winning[34].

In keeping with the shambolic nature of the Election, Allen was blind drunk[35].

Allen managed to keep himself together for long enough to demand the Oath, but he didn’t get much further. An incensed local innkeeper, John Brown, dragged Allen out of the Hall, into the street, and beat him black and blue[36]. Brown, of course, was down on Hunt’s list for £140.

In fact, very few people in Grampound could, with purity of conscience, demand the Bribery Oath. Even the-then Mayor, David Vercoe (or Varcoe), a tailor, was told that

…you know yourself you are as bad as any of us…

~ Lopes Indictments, p11

The list tells us that Vercoe had received £50 from Lopes.

Vercoe did have enough clout to get the Election postponed for a day and, for better or worse, two MPs were finally returned. John Innes and Alexander Robertson carried the day, each receiving 36 votes apiece. Teed received eleven, and only one man voted for William Allen[37].

Robertson was nowhere near Grampound at the time, but did have the good grace to write a letter of thanks to the Potwallopers[38].

If far from being a victory for democratic procedure, it was nevertheless a victory for Masseh Lopes.

A pyrrhic one.

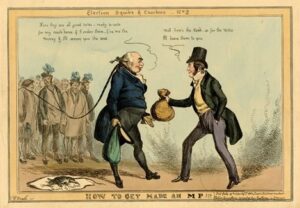

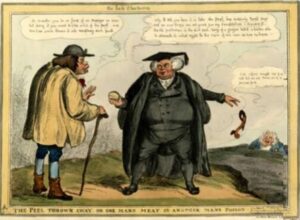

How to Get Made an MP, by W. Heath, 1830

How to Get Made an MP, by W. Heath, 1830

Teed’s solicitors’ bills for the indictments he had prepared against the Potwallopers were offered to be paid – by the Potwallopers themselves. The “Sitting Members” (ie Innes and Robertson) were prepared to slip him £5K (over £350K today), if he dropped the charges. For once, Teed was not for sale[39].

At the Devon Assizes in March 1819, Teed’s own motivations for highlighting the corruption at Grampound were questioned. Was he really

…the unspotted champion of Parliamentary purity?

~ Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 27 1819, p4

Probably not, but then nor was Masseh Lopes. As the “scapegoat Jew”[40] of

…an evil and corrupt Mind and Disposition…

~ Bribery and Corruption, p9

…he received a £16,000 fine and a prison sentence of two years, later commuted to one[41]. He was also the butt of much caricature and satire:

In this etching of 1829, Lopes is the figure drowning in the mire of impurity, bribery and corruption. Copyright The British Museum

In this etching of 1829, Lopes is the figure drowning in the mire of impurity, bribery and corruption. Copyright The British Museum

Twenty-four of the Grampound Potwallopers were sent to Bodmin Gaol, for sentences of between three and six months[42].

The case came to the attention of Lord John Russell (1792-1878), at the time a young MP but a future Prime Minister and one of the key architects of the 1832 Reform Act.

The Grampound election scandal was just the kind of issue a young reforming MP on the rise was looking for, and he shortly moved to have the borough disenfranchised[43].

The reports of the House of Lords’ investigation into the goings-on at Grampound made clear that corruption, bribery and exploitation had been a feature of elections for years.

For example, the Liskeard attorney Joseph Childs was made to produce an account sheet from 1808:

Lopes Indictments, p60. ‘The men’ receiving £1000 were the voters themselves

Lopes Indictments, p60. ‘The men’ receiving £1000 were the voters themselves

Despite a petition to the Commons from the Potwallopers “praying” that Grampound would not be disenfranchised, the borough’s “glory”, stated Lord Russell,

…was gone for ever.

~ Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 27 1820, p2

Innes and Robertson were the last MPs ever returned for Grampound; its seats were transferred to Yorkshire[44].

The Potwallopers were as much a product of a corrupt system as victims of it; greed was their downfall. Likewise Masseh Lopes, though one cannot ignore the antisemitism prevalent in the way his fall was engineered, and mocked.

The Great Reform Act of 1832 disenfranchised 56 Rotten Boroughs, but Grampound, back in 1821, had been the first[45]

[1] Quoted from: https://ecppec.ncl.ac.uk/features/bribery/

2 For more information, see: https://www.johnhampden.org/the-society/society-activities/the-grampound-plaques/

3 See: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/parliament/1818, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Russell,_1st_Earl_Russell, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Peel

[4] For more on the Reform Act, see: Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906, by David Cannadine, Penguin, 2018, p154-66.

[5] Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 27 1819, p3; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grampound

[6] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grampound_(UK_Parliament_constituency)

[7] See: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/schools/content/constituency/ks3-political-reform-constituencies-old-sarum

[8] As defined here: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/potwalloper#

[9] For more on Hawkins, see: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/hawkins-christopher-1758-1829, https://www.cornwallheritage.com/ertach-kernow-blogs/ertach-kernow-sir-christopher-hawkins-boroughmonger/, https://trewithengardens.co.uk/trewithen-gardens/visiting-the-gardens/trewithen-exhibition/

[10] For more on Lopes, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manasseh_Masseh_Lopes, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/masseh-lopes-sir-manasseh-1755-1831

[11] For more on Basset, see Elizabeth Dale’s article here: https://cornishbirdblog.com/the-death-of-sir-francis-basset-the-dunstanville-memorial-carn-brea/. The duel is mentioned in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 7 1810, p3; and the Morning Advertiser, April 3 1810, p2.

[12] For more on Maristow House, see: https://jch.history.ox.ac.uk/article/maristow-house-land-power-and-citizenship

[13] Unless otherwise stated, the main source from this point forward in my narrative is the House of Lords Sessional Papers, 1801-1833, Vol. 127, 1821. These papers include the following three sets of documents: i) Minutes of Evidence Taken Upon the Second Reading of the Bill Entitled An Act to Exclude the Borough of Grampound, hereafter Second Reading; ii) Minutes of Evidence Taken in a Committee of the Whole House on Indictments Against Sir Manasseh Masseh Lopes, Baronet, and Others, for Bribery at the Last Election for Grampound, hereafter Lopes Indictments; iii) Extracts of Material Parts of Indictments Whereon Sir Manasseh Masseh Lopes, and Others Were Found Guilty of Bribery and Corruption, hereafter Bribery and Corruption. These Sessional Papers can be found on Google Books.

[14] For their biographies, see: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/teed-john-1770, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Cochrane-Johnstone

[15] For more on Collett, see: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/collett-ebenezer-john-1755-1833

[16] Lopes Indictments, p54-5.

[17] Lopes Indictments, p17-18. That Edwards canvassed for Teed on behalf of Sir Christopher Hawkins is mentioned on p62.

[18] Hawkins’ attorney, Alexander Lambe, also worked for Teed: Lopes Indictments, p42. See Collett’s connections here: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/collett-ebenezer-john-1755-1833

[19] Second Reading, p43.

[20] This reference to Hoare’s ‘kitchen’ is made in Lopes Indictments, p26; his visit to Lopes is covered in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 27 1819, p3.

[21] Lopes Indictments, p3.

[22] Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 27 1819, p4.

[23] For more on Innes and Robertson, see: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/innes-john-1767-1838, and https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/robertson-alexander-1779-1856

[24] From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grampound_Town_Hall

[25] See: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/hawkins-christopher-1758-1829

[26] Royal Cornwall Gazette, July 24 1819, p4; Lopes Indictments, p22.

[27] From: Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906, by David Cannadine, Penguin, 2018, p181-3, 349-50.

[28] Second Reading, p24.

[29] Second Reading, p33.

[30] Second Reading, p17-18.

[31] Second Reading, p24-5.

[32] Lopes Indictments, p3.

[33] Lopes Indictments, p5.

[34] Lopes Indictments, p63.

[35] This is confirmed by several who were present. Second Reading, p39; Lopes Indictments, p5.

[36] Lopes Indictments, p28.

[37] The numbers are from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grampound_(UK_Parliament_constituency), and obviously must be viewed sceptically.

[38] This brief missive is reproduced in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, July 4 1818, p3.

[39] Lopes Indictments, p31-7.

[40] From: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/parliament/1818

[41] From: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/masseh-lopes-sir-manasseh-1755-1831

[42] They were: Thomas Devonshire, William Allen, Till Baker Johns, Francis Brown Jnr, James Coul, Phillip Luke, George Watts, William Courtis, George Hoyte, Edward Paynter, Richard Ham, James Brown, John Ham, Isaac Watts, Thomas Coade, Samuel Croggan, Thomas Courtis, William Teague, William Nancarrow, Edward Luke, Joseph Vercoe, John Brown, Francis Brown, and Robert Cooke. Bribery and Corruption, p16, 18, 19, 20.

[43] For more on Russell, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Russell,_1st_Earl_Russell, and https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/russell-lord-john-1792-1878

[44] See: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/1821-05-21/debates/1abd9236-215d-451b-ad01-9840d7eea7a0/GrampoundDisfranchisementBill

[45] From: Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906, by David Cannadine, Penguin, 2018, p161-2.

Francis Edwards

Francis Edwards

Francis Edwards runs ‘The Cornish Historian’ website and blog (https://the-cornish-historian.com/), rated one of the top fifty sites on Cornwall. A Camborne boy, he has a BA and MA in literature and a lifelong love of history. Francis generally covers the Industrial Revolution and mining, crime, social unrest and sport. He welcomes commissions for articles, and talks for local history groups.

Wonderful story — brilliantly told