The wreck of the VIKING – March 1872 Harlyn Bay

The Arab at Harlyn (Photo: courtesy Malc McCarthy)

The Arab at Harlyn (Photo: courtesy Malc McCarthy)

John Buckingham brings us a real-life sea drama involving the demise of the barque Viking, and the remarkable bravery of the men of the Albert Edward who went to her aid. Here, there is drama in the extreme in a tale to take your breath away.

“Too much praise cannot be given for the noble manner in which everyone worked in rendering assistance, risking their own lives for the safety of the crew.”

Mostly at weekends, the members of Padstow or Rock Rowing Clubs can be seen out with their splendid pilot gigs ploughing their way through the water in style. One of them is ‘Dasher,’ built by local shipwright Peter ‘Dasher’ Reveley in 1989. just a year after the club was formed. It has recently been restored.

Petroc, Teazer and Arrow

Petroc, Teazer and Arrow

The history of these special craft goes back to the days of sail when they were work boats associated with the shipyards here and elsewhere around Cornwall. In the 1950s some had survived on the Isles of Scilly and were brought by Newquay Rowing Club to the Padstow Shipyard of Steve Brabyn (The Lower Yard), to be brought back to use.

Steve Brabyn was well suited for this work, his father and uncle had both served on the Albert Edward rowing lifeboat in earlier times. His apprentices would soon get to know their way around the workings of a pilot gig. Such is the way skills are handed down through the generations.

Modern lifeboat men and gig rowers alike are in awe of the men who rowed the likes of The Arab and The Albert Edward in times past. One rescue in particular has always fascinated me, and this took place in 1872 on 2nd April. To reach Hawkers Cove from Padstow some of the crew would use the gig belonging to the yard where they were at work at the time of the call out.

Two news reports have survived from that time. The first, reminiscent of the cowboy movies of my childhood, where a lone rider gallops into town with the news.

About one o’clock in the afternoon the inhabitants of Padstow were alarmed by the information brought by a man on horseback riding post haste from the country.

Our intrepid reporter continues to tell us how.

Being within reach of the rocket apparatus, two branches of the brigade were brought to bear, one on each side of the bay – but only one succeeded in getting a line to the ship.

The Rocket Apparatus (Photo: courtesy Malc McCarthy)

The Rocket Apparatus (Photo: courtesy Malc McCarthy)

Another news report was reprinted in the Padstow Echo in December 1996. Under the heading “Man and Sea,” it gives us more detail. From Claude Berry who interviewed him some 50 years later for his book History of Padstow Lifeboat, it would seem to be by William Stribley.

We heard the clap of the maroon signaling, ‘vessel in distress lifeboat crew assemble’. The shout had gone up, a gusting wnw had been blowing all day. We got into our boatyards gig and pulled down to Hawker’. There was no sign of a ship, lifeboat or the cove’s women. I stayed with the gig while the others toiled up Stepper to see what was what. Racing back down they shouted, ‘She’s in Harlyn!’ The lifeboats overland to her! Overland, we know the drill. We’d seen the crew practice for such a moment. The Albert Edward would be rowed up to the harbour. Ten horses collected from the local farms would bring the boat-carriage to the outer slip. The boat loaded. Horses and men would thunder along the quay and take the hill behind St Petroc’s Church at a gallop.

To crest the hill above Harlyn, extra hands would be needed to pull push cajole the straining horses. We returned our gig and I set out with others to run up over and down to the bay, our bodies punching against the wind. We pelted onto the beach with the lifeboat. Three men were being tended to. They had tried to swim ashore and had been pulled out more dead than alive by brave men dashing into the surf. Squinting into the wind I could see her! There, so near and yet so far. Things looked desperate for her. She was beginning to break up. The steaming, quivering horses were being calmed to back the carriage into the surf. The coxswain called for volunteers. I started forward, ‘I’ll go’. The wind sucked aside my shout, returned it to me as a whisper.

My hands trembled as I tied the cork lifejacket on. I could feel my courage seeping out through my boots, so I clambered onto the boat and snatched an oar up from its rowlock, a blue oar. A launch looked impossible. The launchers were up to their chests, the seas so ferocious that they were being washed off their feet. The man at the white oar opposite me shouted ‘Whatever are we going to do.’ I looked over my shoulder at the crippled ship, ‘Why get out to her? What do you think we’re going to do?’ Above the noise of the surf the coxswain was bellowing. ‘Pull, Pull on those oars.’ With a mighty effort the boat crept forward. Seas were slamming down, filling the boat, beating our heads down to our hands. With my eyes blinded I stretched my sinews and concentrated on the coxswain’s roar. ‘Pull blue back white, Pull white back blue, Pull blue back white’. We inched slowly forward.

Then we were up to the barque, the Viking. She was laying bows on, giving us no shelter so we had to work the oars to stay under her bowsprit. Seas tore past us constantly filling the boat. We managed to fire a line to her. Suddenly a man was coming down it. He had an old red muffler tied round him. As his feet touched the whaleback we caught the words, ‘baby, baby,’ our bowman took out his knife, scrambled up to meet him and sliced through the muffler. Then it all happened so fast. The bowman must have seen the wave coming for, baby and all, he pitched himself back in the boat. A huge sea washed over us, broke the man’s hold on the lifeline and swept him clean off the boat. We all watched in horror as the brave man drowned, dragging beneath the waves. (another report gives his name as George Thomas, able seaman native of Bath).

‘There’s more to save yet lads.’ The Coxswain pulled our attention back. Then a woman appeared, seemed to hesitate, said something to the man next to her, then jumped into the waves. She had a lifeline around her waist. She was caught by this and pulled aboard the lifeboat. ‘My baby,’ she cried. ‘Safe Ma’m,’ the coxswain shouted. ‘My husband,’ she pointed. The captain was a man of duty, he saw his crew off first then came down the line himself. ‘Anymore?’ ‘The cook, he’s’… the captain broke off. A figure with a ladder tied to his waist sprang from the deck into the sea, vanished then surfaced and was washed shoreward. ‘Right lads pull, pull for home’. We bent our backs into the job, and with the sea and wind astern we sped up to shore and safety. Men dashed into the surf, their hands stretched out to help. The boat was heaved on to the sand. I struggled up and nearly toppled out of the boat I was so fatigued. I was coughing water and my body felt as if it had been clubbed. Nearby, the captain and his wife and baby were clinging together in silence, exhausted but safe. I could not help thinking about the baby. ‘What a welcome into the world for such a small thing’.

The baby was called Harlyn and went on to become a ship’s captain himself. Records do not say if he ever sailed into Padstow.

We know from other reports that the coxswain was William Corkhill, an experienced coastguard who had served with Newquay lifeboat and would end his days in Port Issac. He, together with Samuel Bate, the 2nd cox, a Port Isaac born Padstow man, would receive a silver medal from the RNLI for their efforts in saving the seven people from the Viking.

Fortunately, the Padstow Station still has the ‘return of service report written by Rev Richard Tyacke the Lifeboat Secretary which lists the 13 men involved.

As well as coxswain William Corkhill there was J Brenton, J Hoskin, A Crennel, E Docton, J Stephens, S Bate, J Knight, J Randle, G Harvey, J Edyvane, N Stribley and G Cotton.

Interestingly, it records the number of times each of the crew had been on a lifeboat to a wreck. S Bate was recorded with 14, Corkhill seven and eight of them only once. Youth and experience.

I attempted to find them on the 1871 Census with limited success. Initials didn’t always match, for example Claude Berry’s William Knight is a ‘T’ Knight on the list. Even the captain of the Viking is George on the lifeboat list and Thomas elsewhere.

We are told that the survivors were taken to Harlyn House, then the home of the Hellyar family who provided sustenance and arranged for a surgeon to be present. It would appear that several civilians came forward to help. One newspaper report states that over a hundred attended.

One letter survives, sent to Padstow Museum in 2003, written by Captain Gentles to Mr Burrows who had pulled one of the crew from the surf.

Letter from Thomas Gentles, Master of the Viking, written from Padstow in 1872 to Henry Burrows, Porthmissen (Trevone).

I observed at the wreck of my late vessel the Viking, someone very forward in assisting such of my crew as were trying to swim ashore. Particularly in saving single handed the first man. I now learn it was you that was so very venturesome and brave, and I beg to return you the thanks of the men you so gallantly assisted and also my own thanks.

The men have left and did not know the name of the gentleman who assisted them and left with me the duty of finding him out and thanking him in their name.

I am sir

Your very obedient servant

Thomas Gentles

Master of the Barque Viking

The Larn Index gives the barque Viking as travelling from Cardiff to Plymouth with coal. One hundred tons of cargo was sold for £93 and what was left of the vessel for £410.

The house that housed the lifeboat carriage still stands forlornly in Trethillick Lane, up behind Prideaux Place, a reminder of these special times past.

The first Albert Edward (1856-1864) was the second of all the Padstow lifeboats followed by another with the same name – a gift of the City of Bristol (1864-1883). A splendid scale model, the property of Bristol City Museum, now has pride of place in the Padstow Museum Lifeboat display. She is recorded as having saved 106 lives.

The Padstow Museum display which shows a small model of the Arab and a larger model of The Albert Edward which was a gift from the City of Bristol. (This model is on loan from the City of Bristol Museum)

The Padstow Museum display which shows a small model of the Arab and a larger model of The Albert Edward which was a gift from the City of Bristol. (This model is on loan from the City of Bristol Museum)

In 2011, treasured items were donated to Padstow RNLI by members of the Corkhill family. They included the silver medal awarded to him on this occasion.

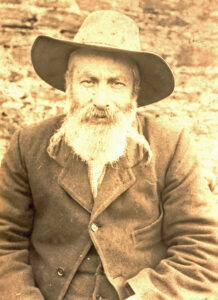

Samuel Bate of Port Isaac – the 2nd Cox (Photo: courtesy Malc McCarthy)

Samuel Bate of Port Isaac – the 2nd Cox (Photo: courtesy Malc McCarthy)

Samuel Bate, one time brewer and landlord of The London Inn in Lanadwell Street, is buried in St Endellion Churchyard (1817-1888) On his gravestone it proudly states ‘He was Coxswain of Padstow Lifeboat for 16 years’. Service indeed.

These words from the past have a way of communicating with us today in this world of blanket television coverage and smart phones that maybe modern technology can never do.

I will leave the final words to one of those early reporters.

Too much praise cannot be given for the noble manner in which everyone worked in rendering assistance, risking their own lives for the safety of the crew. Altogether it was one of the most melancholy though exciting scenes witnessed on this coast for a number of years.

One item mentioned on the ‘return’ was the fact that the Albert Edward received some damage and ‘broke one steer oar and four short oars.’ Testament indeed to the rowing skills of these gallant men.

Postscript:

It would be good to know what actually happened to baby Harlyn. Someone out there must know and maybe they will read this and get in touch.

My grateful thanks to the Padstow Echo, Padstow Museum, Glynis Kent for help with family history research, Malc McCarthy for some of the photographs. To Mike England for ‘the return of service’ and to all at Padstow RNLI, lifeboat crew and helpers along with beach wardens and the local coastguard who continue the tradition of service so admirably shown in this story from the past. Last, but not least, to my wife Liz, for her attention to detail with my grammar and punctuation.

John Buckingham

John Buckingham

‘Spicer Jowan’

Living in Padstow and loving the stories I have learned from my life here has given me the encouragement to write about some of them. Thanks too, to my friends, past and present, in Padstow Museum and the Old Cornwall Society and to the opportunity given to contribute to the Padstow Echo over a period of many years.

What a story! Brilliantly told. Brought it to life.Thank you. Would be good top know what happened to Harlyn.I have developed a soft spot for these stories of bravery since many of my more distant family were seafarers (SE Cornwall – Navy and lifeboatmen) and one (sort of related!) survived a wreck in the Bay of Biscay.