Knees Department Store, King Street, Truro

Knees Department Store, King Street, Truro

Susan Coney brings us her experience of being a young Cornish Maid in a man’s world.

I took my ‘O’ Level GCE’s in the summer term of 1964. During the summer holidays, I worked in Knees toy department. Whilst I was there, the girl who was the department supervisor, left and the manager asked me to do the ordering. This involved checking the stock at the end of each day and completing, by hand, an order form which was quite a laborious task, but my handwriting then was very neat.

Before I left, the manager offered me a permanent job. I was flattered but had already decided that I wanted a job in science.

My ‘O’ level results were quite good, and I was especially pleased with my physics and chemistry grades. I returned to school in September – in the 6th form.

I went to see the physics teacher and asked her if I could join her ‘A’ level class. She was not very helpful, saying that her class was full and that all the girls in the class had very good grades. She asked me what grade I had and when she realised that I had a higher grade than anyone else – she was surprized and said that I’d better join the class. I was not very pleased as she had not even looked at the results of everyone, just those from the alpha form (the highest stream) and not all the 5th form classes.

So, I began studying for 3 ‘A’ Levels – physics, maths and art (not a traditional combination) but I enjoyed art as I found it relaxing.

The first physics class was a disappointment – the teacher just opened the first page of the book, Advanced Level Physics by M Nelcon and P Parker, and read the first chapter – no teaching or explanation involved. It was an all-girls’ school and in the 1960s, physics was not a subject thought suitable for girls to study. I did not have any encouragement from the teachers and got the impression that none of them thought I was capable of going to university, being from a working-class family. That is what it was like in the 1960s. I now know that with a bit of encouragement I was worthy of a university education.

Soon after, I became disillusioned with my academic studies and had to decide what career I wanted to pursue. The jobs available in Truro, or nearby, were limited: work in an office? – no, be a secretary? – no way (I would probably tell my boss to fetch his own tea or coffee and get the sack), work in a bank? – no, work in a shop? – no. That was about it. I thought about going to teacher training college but again, I had lost my confidence in being able to get a place at a college – you didn’t have to have ‘A’ levels in those days just ‘O’ levels.

I didn’t want to put any financial burden on my parents as my sister had just started at the grammar school and to have two girls to support with uniform etc, would have been even more of a struggle for them. Also, I think my parents knew that I was not happy to continue in conventional education.

My Aunt, who lived in Tuckton, near Bournemouth, found an advertisement in her local newspaper for Scientific Assistants working at a government research establishment in Christchurch, Hampshire, which included part-time study at Bournemouth College. I applied, went for an interview, and was offered a place which I accepted.

When I went to the head mistress, who was a nice lady, to tell her I was leaving, she had tears in her eyes (but she did that with everyone who told her that they were leaving). She also said she had wanted me to be the Head Girl in the final school year! If only she had said that before, as it could have given me the confidence I needed.

The job meant that I had to leave home but my Aunt found me bed and breakfast accommodation near to where she lived (she was the matron of an old folks’ home in Tuckton). So, after Christmas December 1964 (I turned 18 on the 30th), Dad drove me up to Tuckton and on 1st January 1965, I started work at SRDE Christchurch.

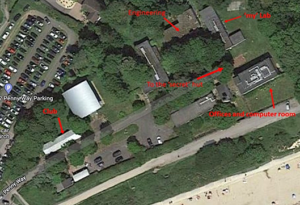

I had to report to the main site at Somerford where I was given a short induction talk and had to sign the official secrets act! I was then taken to where I was going to be based which was at a small outpost at Steamer Point overlooking the sea. Steamer Point was a collection of war-time looking huts – just like the ones in old films. There was one more modern two-story building which was the administration building and on the first floor, I later found out, was a computer! I also discovered later that there was another very secret hut up in the woods. The site looks the same today.

The folks that worked there were highly qualified and experienced research scientists inventing new radio communications and other equipment for the army, and I was there too – a young maid from Cornwall.

The work I did included helping with the research into the effects on a radio signal by such land features as trees and hills and the result that the ionosphere had on a radio signal. All very interesting. One thing I did was to look at Ordnance Survey maps to find a hill with one tree on top so that an experiment could be done to measure the loss of signal. I found one in Dorset. So off I went with another member of the team in an old army truck to do the experiment in the field. The result was a 4db loss of signal.

For the experimentation that the ionosphere had on a radio signal, the scientists had built their own transmitter: it was in Gozo, Malta, and the receiver was at Ventnor. This kit was built with the old electronic components with valves etc. The analogue signal data was punched onto a paper tape. Periodically, the equipment needed to be checked and the paper tape collected. This meant a trip on the ferry to the Isle of Wight in the old army truck – and I went too. All extremely exciting and interesting stuff.

We also did experiments near the Bovington Tank Training Camp. On one occasion, we were parked in a roadside lay-by when a tank came along the road, turned into a track opposite, swinging its gun around and taking our ariel with it. We were fine as was our truck but the SSA (Senior Scientific Assistant) was not best pleased and had to run after the tank to retrieve our precious ariel.

Later, one of my tasks was to take the analogue paper tapes from the receiver in Ventnor to the computer and run them through a programme to convert them to a digital printout so that the results could be read by the scientists. The computer was an Elliott 803, a single program machine with 8K of memory. A task that was to become very useful in my later career. The results showed that in certain circumstance, the ionosphere would enhance a signal.

On a couple of occasions, we were told to stop work and not talk. Why? Because a Russian submarine had been detected just off the coast and could be listening in to our activities. It was like being in a film. I later found out that in the top-secret hut in the woods was where the experimentation on infrared night vision was taking place.

Another task I had was to wire up very small electronic boards using miniaturised components like transistors, resistors, diodes etc. I was taught how to solder using a heat sink. I did this as I had small hands and fingers. Once the night vision technology was perfected, the kit needed to be miniaturised such that it could be put in a pack which a soldier could wear on the back of his helmet. I like to think I helped to develop this kit.

The site also undertook experimentation into different types of ariels – specifically the log periodic – but the most exciting was the dish aerial – the one which is very familiar to everyone now, but this was the mid-1960s. One or two were positioned just outside the Steamer Point entrance in inflatable domes. The local people were very suspicious of the domes thinking they housed something very dangerous. The idea was that a dish ariel could be mounted on the back of an army truck and radio signals could be bounced off any old space junk and reflected back to the receiving dish ariel on another truck – thus providing mobile communications across a battlefield.

The senior scientists also did experiments using lasers for communication – (but maybe this was fibre optics?) – I remember a bright red light being shone across the lab and me walking in the door and being told to stand still and not look down the light. It gave a perfect signal with no power loss but only in a straight line!

The people I worked with were amazing – from the Lab Technician – a very quiet older gent who was a rear-gunner on bombers in the war and who made the tea and painted TO (Tiddy Oggy) on my tea mug, to the boss, a typical mad scientist type. Once, the boss was doing an experiment in the lab (where I sat in the corner) and needed to plug in just one more scope and hunted for another extension lead and found one in the back of a cupboard. I think it was the SO (Scientific Officer) who said, “Don’t plug that in, it’s damp”. Too late, he did and blew all the electrics in the building.

The person I worked with mostly was the SSA (Senior Scientific Assistant). Another more experienced SA (Scientific Assistant – as was I) often gave me a lift to and from work, so I didn’t have to catch the bus.

The SO was quite a big built man who I initially thought was a bit fierce but was actually very kind and helpful – a gentle giant.

Steamer Point today on google maps.

Steamer Point today on google maps.

All the team were very supportive and gave me many opportunities to learn. They looked after me too, as I was the only girl on site apart from the Head of Site’s secretary.

They did play a trick on me soon after I joined. One of them asked me to go to engineering (which was in the hut next door to our lab) to fetch a bit of kit and ask for a gentleman who they called by his nickname. Me, being a naïve very young Cornish girl, didn’t realise that his nickname was a slightly rude one. I did as instructed, – and asked for Chopper – much to the amusement of the engineers and my work mates – the rotten devils!

The club house and bar was located in the first hut on the left, just inside the gate. I can’t remember if there was a restaurant but I think the bar sold pies and suchlike. I remember there being a shove ‘alfpenny board in the bar which I played often and got quite good at.

In the summer, some staff went down to the beach with their bathing costume rolled up in a towel. Then we were asked to put our towels and costumes in a bag as people thought the site was a holiday camp!

In December 1965, I was featured in a series of photos taken for a satirical Christmas presentation. Photos of the ‘Head of Site’ were superimposed on the young man’s images and from the supposed position of the young man’s hand, you can just imagine the inference! His hand was actually on the machine, not me!

The ’machine’ in the background was on the secret list at the time.

The ’machine’ in the background was on the secret list at the time.

I had day release (one full day and one evening) to study for an Ordinary National Certificate in physics, chemistry and maths at Bournemouth Technical College and in June 1965, I was sent on a six-week residential electronic course at the Royal Radar Establishment’s own college in Malvern. There were about 20 young lads on the course and me – the only girl.

On the first day, one of the lecturers came into the classroom, looked around and spotted me. “Oh dear”, he said, “we have a girl – you’re not going to be any good, are you”. You could say that in those days. I said nothing. At the end of the six weeks, we had several exams (all open book) followed by a long weekend off when I went home to Cornwall. On our return to the college, we were called in one by one to the lecturers’ room to be told our exam results. When it was my turn, the lecturer (the one who decided I wasn’t going to be any good) said, “You’ve done very well, you were fourth in the class”.

“Oh good”, I said, “and I’m a girl!” There was no reply!

What an incredible time I had in my new job – so very interesting and a good grounding for my future career.

I also had good times living in the area – it had a good nightlife and was near the beaches – but I was homesick and left after about two years as my Dad was not well and I wanted to go home to be near my family.

During the few months back home in Cornwall I looked for a job in science but there still weren’t any. So, I left home again and went to London. I worked for various companies initially as a Computer Operator, then as a Programmer. I then trained as a Systems Analyst and Computer Systems Designer and part of the training was to attend an intensive course for several months at Kingston College. Once again, I was the only girl on the course and all but one other attendee had a degree and two of them had a PhD – both from Cambridge! There was me, that same little maid from Cornwall but a bit older and wiser, with only ‘O’ levels and an ONC. Um, I thought, I’m going to have to pull my socks up to get through this. The first lecturer entered the room and looked around, seeing the one girl in the class but this time he made no comment – times had changed in a few short years.

It was an intensive course followed by several exams – none of them open book this time – and a viva. After the final exam we had a couple of days off and when we returned, the results were displayed on a flip chart at the front of the room. I looked through the list specifically to find the young men with PhDs – they had done very well! Then I realised everyone was looking at me! I had beaten the lot of them – that little Council house maid from Cornwall! I may not have had a university education but I had the practical experience that the rest of the student did not.

As my Mum would say, “You can do anything you want to if you work hard, have determination and try your best”. I will be forever grateful to my parents who both came from humble backgrounds but were skilful and talented in many ways, and very wise. My Dad was a farm worker when he was young but was a natural craftsman. He became one of the few skilled engineers retained on the assembly of Spitfires in WW2 at the Secret Spitfire Factories in Salisbury. My Mum was a draper’s assistant from aged 14 and became the main cashier for the store. Both my brother and sister have had successful careers as have our children. I believe the qualities of the Cornish live on through the generations.

Susan Alecia Coney (nee Phillips)

Susan Alecia Coney (nee Phillips)

I was never very interested in history at school but following retirement, I decided to trace my family history. I told my Mum and her reply was, “I wouldn’t bother m’dear – we know zactly where we come from – a long line of serfs”.

However, I wanted to find out if there was any truth in the family stories. My Dad used to say ‘it’s all bunkum’ but I have proved that they are true. I also wanted to find out why I, and most of my family, feel so passionate about being Cornish.

This then, was the start of my interest in history – especially Cornish history: of its people and places. My Cornish family may not be descended from the rich and famous, but our ancestors were incredible people and I recognised the importance of documenting my research and personal memories so that it could be appreciated by later generations.

Really enjoyed reading you story.

Thank you Margaret – different times now but interesting to remember as it was.