Dean Evans is an authority on John Passmore Edwards having written the book “Funding the Ladder” and delivered many talks about his life. Here, he has condensed it into an article for Cornish Story.

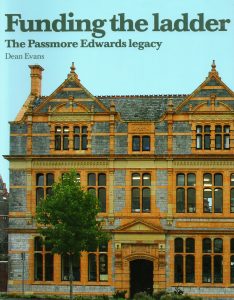

“Funding the Ladder” by Dean Evans

“Funding the Ladder” by Dean Evans

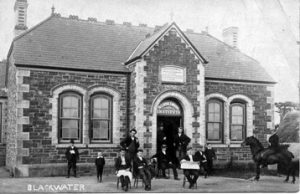

The engraved stone over the doorway to the Blackwater village hall states that the building was a gift to the village of Blackwater “by John Passmore Edwards, of London”, The donor was in fact a Blackwater lad, born in the village in 1823 and “of London” describes, in the eyes of the then villagers, the elevation to which this local boy had climbed.

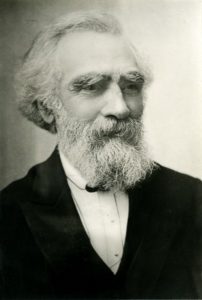

Passmore Edwards, as he was later to be universally known, was one of five sons of William Edwards and Susan Passmore, born on 23 March 1823. His father was a carpenter and with a growing family built a house to accommodate them. Their first child, James, died as an infant but the other four sons, another James, Richard, John and William grew to maturity.

To keep his family, William established a brewery at the house, making and selling beer to other beer houses in the neighbourhood, and the boys were expected to help. When pumping at one of the local mines disturbed the water supply to the brewery, William developed the land around the house as a market garden and the boys were again set to work: tending plants, picking fruit and taking it to the market in Redruth, St Agnes or Truro. I may write about James, Richard and William at another time but this is an account of the life of John, known as Jack to his school friends, and arguably one of Cornwall’s most famous sons. His father thought it worthwhile to pay the 2d a week for the boys to be educated at the local Dame School, where, according to a fellow pupil the children of mixed ages sat eight to a bench. His father also took a weekly paper, the Penny Magazine, and reading of the famous people there aroused in young Jack “an ambition to be useful”, which was to remain with him for the rest of his life. In his early teens he became a Sunday School teacher and with a school friend, John Symons, started a little evening and Sunday school for the men and boys of the village who could not read and write and could not afford the 2d a week for the Dame School. This was held at the Bible Christian Chapel at Wheal Busy and was quite successful, continuing for many years after Edwards left the area. Edwards said that amongst his greatest possessions were a few letters he had received in after years from men who had learned to write at that little school. He also tried his hand at public speaking, first at the Carharrack Institute, which he attended with his Uncle John who was a Greengrocer in St Day. These early attempts were not successful, neither was the poetry that he sent to the editor of the West Briton with a hope that it might be published. The rejection letter: that his poetry was “not worth even the paper it was written on” also remained in his memory. But his perseverance won through and within a couple of years he was lecturing at Men’s Institutes in Truro and the surrounding villages.

When he heard about the Anti Corn Law League, Passmore Edwards, still a youngster, sent for a pamphlet so that he could understand more of their argument but was surprised to receive not one but a parcel of pamphlets and a note asking him to distribute them in the area. This he did, walking as far west as Penzance, more than twenty miles away; much to the annoyance of the Mayor who was a Magistrate and who threatened that he would have him arrested and put into prison for sedition.

He worked for a while as an assistant to a solicitors Clerk in Truro, at the princely wage of £10 a year, taking a lodging in Truro during the week and returning home on Saturday evening. Each Monday he would set out to walk the 6 miles to Truro, taking with him three of his mother’s pasties for his dinner during the first three days, and would either walk home to collect another three for the rest of the week or they would be delivered on the carrier’s cart.

Whilst living in Truro he took it upon himself to travel to Bodmin, to witness the public execution of the Lightfoot brothers, who had been convicted of the murder of Neville Norway. More than 20,000 people attended, with special trains that stood alongside the gaol so that the passengers could view the hanging from their carriage. Edwards walked the 20 miles home to give himself a chance to consider what he had just witnessed and was to campaign against capital punishment for the rest of his life.

His career in the solicitor’s office lasted about eighteen months before he was told his services were no longer needed. Thinking he might be suited to journalism he visited the West Briton Offices and was lucky enough to meet a representative of a London Radical newspaper, who hearing of Edwards’ interest in the Anti Corn Law League, offered him a job as the paper’s representative at £40 a year. The only drawback was that the job was in Manchester. Unable to afford the rail fare to Manchester he walked to Falmouth to catch a steamer to Dublin, as deck passenger, and from there to Liverpool. Finally, by train to Manchester.

We do not know whether he actually signed the pledge, but when the expected salary did not materialise he toured the Temperance halls throughout Lancashire, Cheshire and into North Wales, giving lectures for a couple of shillings a time. Temperance societies were among the earliest advocates of the Samuel Smile’s belief that self-help was the best means of moral regeneration, a philosophy that appealed greatly to Edwards with his nonconformist background, and his own determined and successful efforts to improve himself. Finally, he decided to move to London, where he took a job as a publishing clerk but continued with his lectures, and his education. By now he was very much involved in both social and political reform, becoming an active member of The Society for the abolition of Capital Punishment; The Political and Financial Reform Association, The Society for the abolition of tax on knowledge; The Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade; The Peace Society and many more. His involvement with the peace movement lasted more than six decades. As a member of the London Peace Society, he was chosen as a delegate to attend conferences at Brussels (1848), Paris (1849), and Frankfurt (1850).

He lived a frugal life, by now mostly teetotal and vegetarian, and within five years had saved £50, which he considered enough to start a publication of his own; The Public Good, a small weekly magazine, of which he was publisher, editor, advertising clerk and responsible for most of the articles. However, although he managed to sell thousands of copies a month, the cover price, kept low to be affordable to the working classes, was too low to show a profit. To prop up the Public Good he started other titles, but each had the same problem and his debts increased. Finally, his health broke under the stress and whilst he was ill he was declared bankrupt, his creditors only receiving five shillings in the pound.

Within six months, however, he had started writing again, publishing a political pamphlet denouncing the Crimean War and continuing with his lectures. Slowly things started to improve and he managed to buy a rundown weekly magazine called the Building News, on what he called easy terms, and with his hard-earned publishing skills he turned the magazine around making it very successful. Heartened, in 1869 he acquired, for only a nominal sum, the Mechanics Magazine, which proved another financial success. Although he was legally clear of his previous debts he vowed that he would repay his creditors in full and by 1866 he was able to do so. They were so surprised that they arranged a dinner in his honour and presented him with a gold watch in appreciation.

In 1876 he added the London Echo, a major daily newspaper, to his portfolio and was on his way to becoming a wealthy man and to be described as “one of the kings of modern newspaper enterprise”. His thoughts turned to parliament and he was eventually chosen to represent the Liberal party in Salisbury. He entered the House of Commons in 1880 but found the experience unrewarding, calling it the House of Waste, and not “such a fruitful field of usefulness as … expected” and although being an active backbencher he did not defend the seat in 1885. He considered that he could more easily make the changes to society that he wished outside parliament and looked for ways to accomplish this. The opportunity arose in 1889 when the vicar of Mithian wrote to him asking him for a few books for a men’s reading room he was to create in Blackwater. Edwards responded with an offer of 500 books but added that if a plot of land were found he would fund a new building. The Blackwater Institute was opened in August 1890, to become the first of 70 public buildings that were to be created by his bequests, in Cornwall, Newton Abbot, across the south of the country and in the poorer areas of London. Yes, he built libraries, 24 of them, but also eight hospitals, five convalescent homes, homes for people with epilepsy, three art galleries, a museum, public gardens and countless drinking fountains, all funded from the profits of the Echo and his other publishing enterprises. The 500 books for Blackwater grew to more than 80,000. He gave 1000 books to every public library that was built in London and offered to build a library in every major town in Cornwall. As economic with his time as he was with his money he would travel to Cornwall to open or lay the foundation stone for several of his buildings during the one trip, and in London he was to attend more than one ceremony in a single day, each to be accompanied by speeches and votes of thanks from the communities that received the buildings. Uniquely, I think, he remained connected to many of the associations and organisations that he helped, becoming the Vice President of the Society for Epilepsy and sitting on the Board of the Royal Cornwall Infirmary and the Charing Cross Hospital, and remained a paid-up member of the Blackwater Institute up until the year that he died.

The Passmore Edwards Institute at Blackwater

The Passmore Edwards Institute at Blackwater

By the time he died, in 1911, he had given away more than 90% of his personal wealth but even in his last days saying that his work was “not yet done”. It is difficult to assess just how many people have been helped through one of Edwards gifts. It includes every one of us who has attended one of his libraries or have been treated at the hospitals he funded. Hundreds of thousands will have spent a short period of convalescence at the convalescent homes, and thousands of children from the East End of London were treated to a couple of weeks of good food and fresh air at the Clacton Holiday Home. How many more have walked in the public gardens or drank from a drinking fountain? Today, many of the buildings, no longer needed for their original purpose, have found new uses. The convalescent home at Perranporth, dedicated to his mother, was converted to apartments several years ago, as was the library at Launceston and the institute in Chacewater. In London, two former libraries are now successful theatres and in Bodmin the old library building still serves the community but now as a performance space and community arts enterprise.

John Passmore Edwards

John Passmore Edwards

In 2023 it will be the 200th anniversary of the birth of Passmore Edwards and I am part of a small group of people who are planning to ensure that his name is never forgotten. During a spring and summer festival of events, in Cornwall and wherever the name Passmore Edwards has appeared over the doorway of a public building, we will be remembering the contribution that one of the sons of Cornwall has given to us all.

Camborne Library

Camborne Library

Newton Abbott

Newton Abbott

Southwark Library, London

Southwark Library, London

Cover photograph: The birthplace of John Passmore Edwards.

Dean Evans

Dean Evans

When I first came to work in Cornwall in the late 1980s I very quickly noticed the name “Passmore Edwards” over doorways to libraries across Cornwall. It was some years later, when taking a night class on website design, and needed a subject for a test website, that I thought that some of these buildings might fit the bill. By coincidence, that weekend, I found a slim biography, “The Life & Good Works of John Passmore Edwards” by R S Best, at a tabletop sale. It really did change my life. The test website developed into www.passmoreedwards.org.uk, with regular trips to London, visiting the British Library and the Newspaper archives, and as many of the Passmore Edwards’ buildings as I could. Online research located descendants, and more books; my knowledge of the Victorian era expanded exponentially. Buying a camera to record images of the buildings led to a new hobby in photography and new friends in Camera Clubs across Cornwall. In 2007, finding the Blackwater Institute closed and semi derelict, I started a campaign to restore the building for use as the village hall, learned new skills in writing bids for grants and seeing opportunities to raise money, found a lasting relationship with this wonderful community, and received a BEM. The website developed into a book, credited with a Holyer An Gof prize, and in 2011 arranging for more than 80 events, held right across the country, from St Ives to Herne Bay in Kent, to mark the 100 years since Edwards died. My interest has made me realise that the issues that Edwards campaigned over are just as relevant today as they were over a hundred years ago. It is an interest that will remain with me for the rest of my life.

Dean Evans

Fabulous short read, thank you Dean!

What a man he was. You are keeping him alive. He wont become just a dry and dusty Victorian memory.

I heard about this wonderful man on Radio Cornwall today, I have seen his name on buildings previously, but hadn’t realised what fantastic achievements he had made to bringing lots of good deeds to the working classes, not only here in his homeland, but also in London. A very humbling story indeed.

Thanks fir sharing.

What a phenomenal philanthropist Passmore Edwards was.

Thank you for your work to preserve his memory.

Thanks for this. I’ve reserved the book at Camborne Library (which is no longer in Passmore Edwards building, unfortunately) and look forward to reading it. He sounds a great man.

Thankyou so much for this. As a native of Cornwall I have been curious about this man for many years but never got around to reading his story. As part of the 200 year anniversary celebration of his birth 2 giant puppets of John Passmore and his wife were paraded through the streets of Penzance last week during Mazey Day. I am now wondering how much involvement his wife had in supporting him and the various projects John Passmore undertook (as she isn’t mentioned in your article.)

Eleanor was much involved in his work. Whilst he was on the Development Board of the Charringcross hospital, Eleanor was part of the ladies guild, fundraising and even making garments and bed linen for the patients. After Edwards had provided the farm that became the national home of the Epilepsy Society, he was made a VP, and Eleanor Warden, taking over the role of BP on his death in 1911. In Cornwall she undertook the choice of furnishings for both the Falmouth hospital and the Perranporth Convalescent Home, and she was usually at his side when the buildings were opened. Edwards, however, did not mention his family life very much so much of what Eleanor accomplished is in recorded. Sorry for the delay in responding. Do email me if you would like to know more.

Excellent article, thank you. Do you know why Passmore Edwards was particularly interested in Epilepsy?

Sorry for the delay in responding. Edwards seemed to be interested in everything and when a need was brought to his attention he considered how best he could help. Providing the farm was an example of his view that if you provided the ladder the poor might climb, giving those in need the means to help themselves.

Thank you so much!

I have used the Newton Abbot library for many years, not fully appreciating Passmore Edwards, but knowing the connection with this lovely public building.

Additionally, when I was a child in London I almost weekly walked to the local library at the Elephant and Castle. I did not realise that it too was a gift to us all from this dear man.

Without the library to attend I would never have developed the love of books and knowledge that I now have.

My thanks to him and also to you for making the connection.