David Oates is a frequent contributor to Cornish Story and here he turns his attention to Cornwall’s industrial past as he begins the story of tin extraction at Gwithian. Part two, Processes and People, will follow next month.

Tin streaming rates as one of the oldest of Cornish industries with a pedigree stretching back into pre-history and pre-dating deep, hard rock mining by many centuries. This, however, recovered alluvial deposits found in the streams that ran down from the granite uplands – a far cry from the streamers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who, essentially, found their living in the tin present in the waste from the deep mines or in tin that had “escaped” from the treatment works on the mine sites. This is clearly evidenced in the lead photo showing the impact of inland mining on the north coast of Cornwall at Godrevy and Gwithian.

Any river that had its source inland amongst the deep mines would have had its attendant stream works but by far the most important area was found along the course of the aptly named Red River running from near the great Wheal Grenville mine at Troon, through the mining areas adjacent to Camborne and Pool, until it emptied into the sea between Godrevy and Gwithian – an area where the landscape has been more managed and changed by the hand of man than any other part of the Cornish coast. Known as a river, it was, and still is to some extent, an industrial drain carrying tin waste and its accompanying toxic components discharged by many mines along its course. Though deep mining is recorded in the area from the late 17th century, this river valley played its part in the much earlier recovery of surface alluvial deposits. There are records from the Tudor period from areas above Barripper that indicate the local landowners/farmers were recovering alluvial tin from the streams on their land that became tributaries of the later known Red River (A Buckley 1996). However, the more modern streaming endeavours along the length of the Red River varied from the relatively large, in an attempt by the mines to recover as much ore as they could, to small undertakings run by a few individuals. Two, near Menadarva, some two thirds of the way along the valley from the river’s source, were tiny ventures run, respectively, by the Mounce and Luzmoor families.

Two thousand years ago, according to interpretations of the archaeology by the late Professor Charles Thomas, an acknowledged expert on this area, this valley, in its lower stages, was a sheltered tidal estuary – a rare occurrence on the unforgiving Cornish north coast, with the sea stretching over a mile inland. It no longer does so and this needs to be explained to appreciate the significance of the Gwithian Tin Sand Works, literally on the seashore.

According to Charles Thomas, there is evidence that two thousand years ago the tidal estuary ran inland for about a mile, reaching Reskajeage with small settlements around it – possibly navigable if we take on board the incursions noted in legend by the Irish “saints”. The extent of this estuary was diminished by historic “sandblows” when great movements of sand overwhelmed both the settlements and parts of the estuary. One major incursion of sand seems to have occurred in the immediate post-Roman period, in-filling the furthest extent of the estuary closest to Reskajeage and another, more prolonged period in the 11th century when the rest of the estuary became more silted up and one settlement was abandoned for another on higher ground, less susceptible to the invasion of blown sand. At some stage, a feature known as a “storm beach” was also formed at the mouth of the estuary, further preventing access from the sea. This was exacerbated in further centuries with the development of deep mining in the Camborne area with vast quantities of waste material from the mines being discharged into what became known as the Red River, causing major infilling of the whole valley. At one stage in relatively recent history, South Crofty had permission to discharge 750 tons of material into the river daily – though we do not know if that limit was ever met. This mining discharge contained quantities of tin ore, either lost by the mines through poor maintenance of recovery methods or because some tin ore was not easily recovered at source before the development of more modern chemical flotation methods. The tin recovered by the streamers was far and away easier and cheaper to recover than by sinking a shaft several thousand feet below the ground with the sometimes ruinous costs involved. That material was treated again as it went through the valley, but much reached the seashore at Gwithian and was concentrated on the beach by the action of wind and wave. Therein lay the opportunity exploited by the Gwithian Tin Sand Works.

Tin has been recovered from this valley near the coast for a long time, exploiting the discharge from the mines inland. A number of companies have worked the area over the years and we know that it was worked at the beginning of the twentieth century by a family named Stephens and it appears that samples taken from the area showed very good results. They were treating some fifteen tons a day with a content varying from 20-48lbs of tin concentrate per ton – much more than results from most underground operations and without the financial input required for deep mining.

The treatment works was situated immediately adjacent to the Red River to take advantage of the abundant waterpower to operate parts of the recovery process. It is worth noting that the Red River at this point, very close to the beach, was canalised during the nineteenth century by the Basset family, presumably to increase the flow and possibly bring the water to an already existing treatment works. The original course of the river ran diagonally from near the present road bridge, across the former estuary, to meet the sea close to the steps now leading onto Gwithian beach. The banks and low cliffs formed by the river can still be made out – seen here in picture 2.

Picture 2

Picture 2

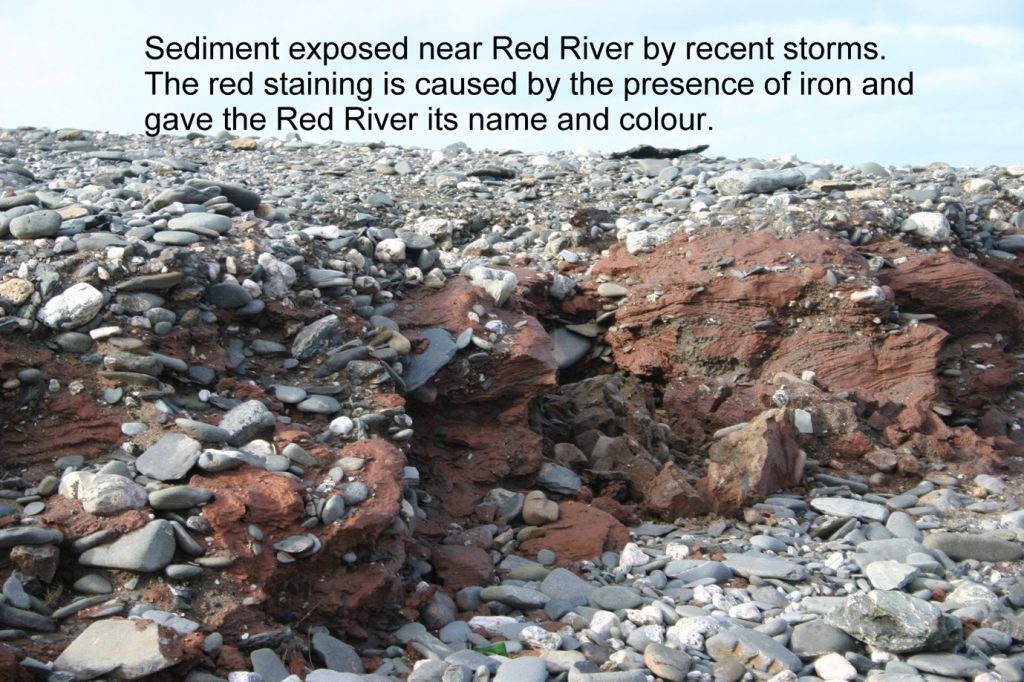

The nature of the deposits brought down by the river is clearly evidenced in Picture 3, which shows the deposits, still extant, in the banks of the river when exposed by flood or storm.

Picture 3

Picture 3

This canalising of the Red River in a previous century caused some degree of difficulty for the Tin Sand Works in its most recent incarnation as, although it was conveniently situated to source the power of the river in its present course, it was not necessarily close to the tin bearing sand as, already mentioned, this was subject to the vagaries of wind and tide. Therefore, before examining the nature of the treatment works it is important to look at the varied ways of getting the tin sand to the treatment plant and how these became more sophisticated and mechanised as the works developed. The difficulty in reaching and recovering the deposits – and the ingenuity needed in surmounting it – is shown clearly in picture 4, taken – not at low water but very close to it – showing the location of the Tin Sand works and the location where the richest deposits were frequently found. Recovering this meant bringing it along the beach back to the works. The picture clearly shows that between the deposits and the works is an outcrop of rocks – the wave-cut platform – that prevented any wagon – horse-drawn in the first instance – from accessing the area other than at low water with a narrow window of opportunity to recover tin sand before the rising tide made this impossible.

Picture 4

Picture 4

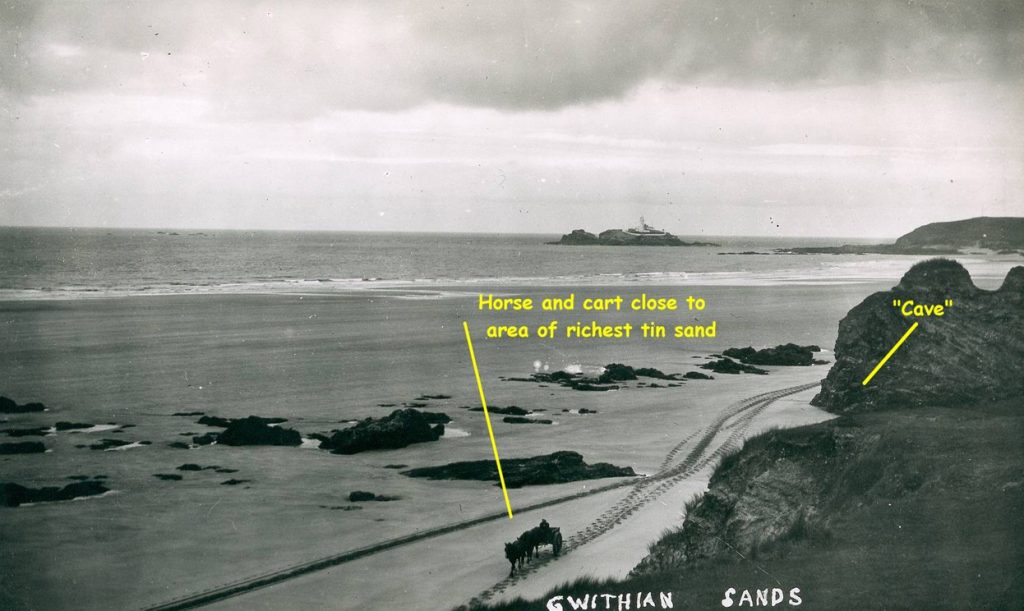

Picture 5 shows a horse and cart en route to the deposits at that advantageous period between tides. This picture does not show the problem of the rock outcrops shown in picture 4. The tracks in the sand show that several trips had been made during this period of recovery. The feature marked “cave” on this picture is directly relevant to this problem and was part of the development of the methods of recovery.

Picture 5

Picture 5

This tidal issue meant the plant was not operating at full efficiency and was, furthermore, sometimes dangerous with the horse and cart being swept away on at least one occasion. We will examine an eyewitness account of such an event further in Part 2 of this writing.

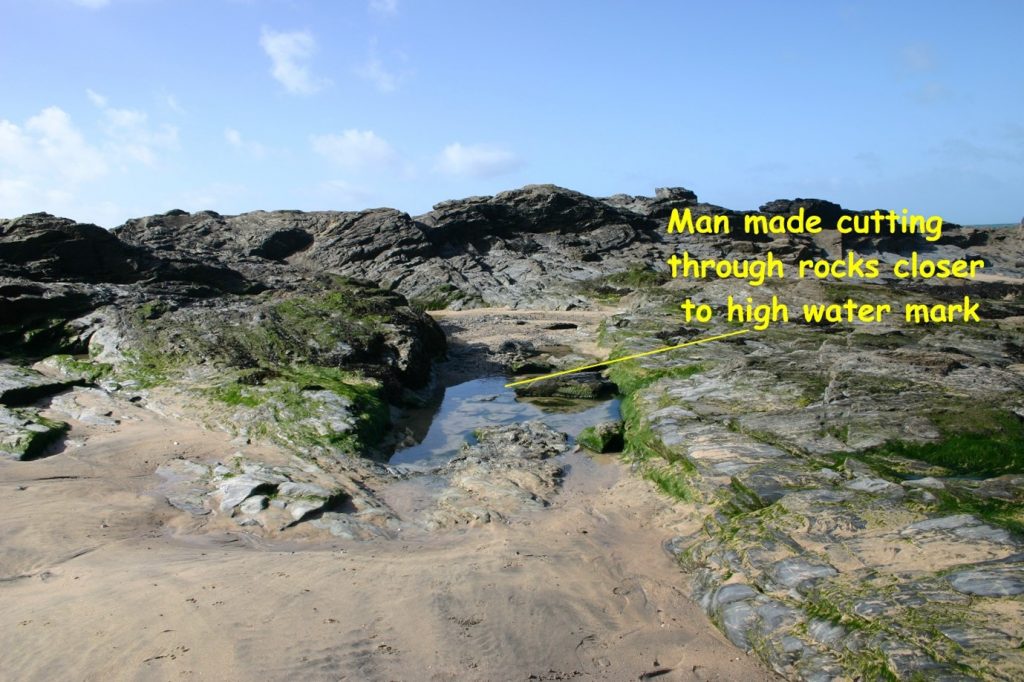

Possibly because of a combination of both these concerns – economic and human – a solution was found – in the best traditions of Cornish ingenuity – when a cutting was created through the wave-cut platform – an easy task in an area with so many redundant and available miners! Pictures 6 and 7 show aspects of this man-made cutting which can still be seen starting at the foot of the steps leading to Gwithian Beach.

Picture 6

Picture 6

Picture 7

Picture 7

Clearly this made an immense difference to the amount of tin sand recovered on any tide. The distance covered was marginally shorter and the recovery could continue from shortly after the tide began to drop until it regained that point again, possibly doubling or tripling the time available to work.

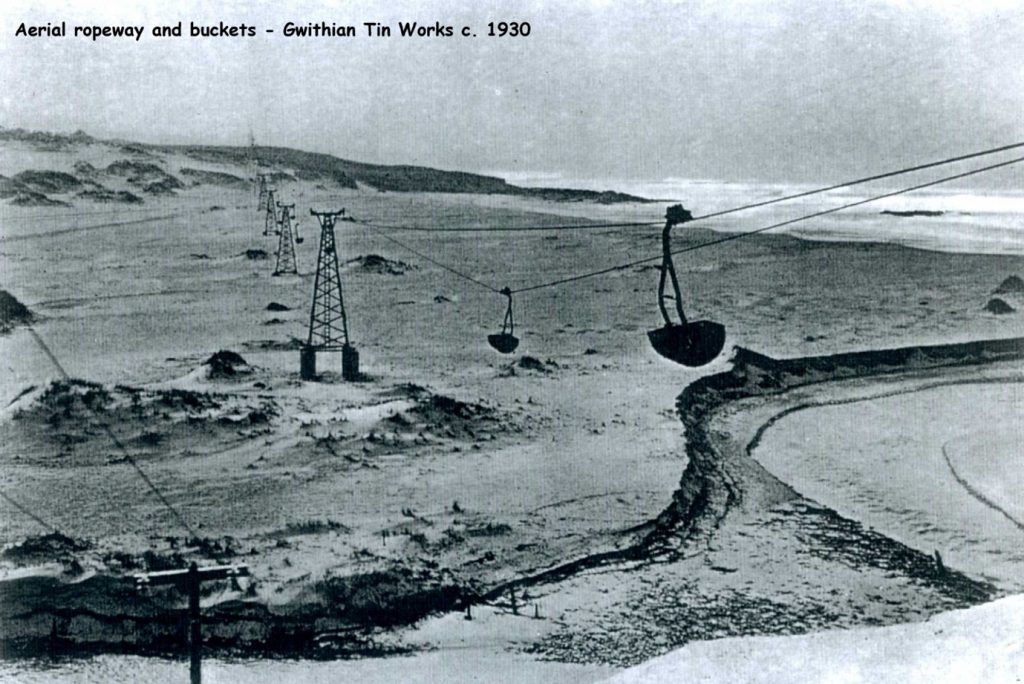

Recovery in this way, although improved, was still at a fairly rudimentary level and a number of other methods of transporting tin sand were developed. Picture 8 shows a reasonably sophisticated way of transporting the sand overland rather than just across the tidal stretches. A series of pylons was constructed from the recovery works across the dune and cliff-top to a spot adjacent to the richest deposits. These supported an aerial ropeway carrying a continuous line of buckets from the source to the treatment works.

Picture 8

Picture 8

On reaching the point on the cliff-top nearest the deposits, where an engine to drive the mechanism was situated, a line ran from the clifftop to an anchor point in the rocks on the beach from where the sand could be carried, without delay, back to the treatment works. In fact, there were two aerial ropeways, with another going further inland to the lime-rich sand of the dunes. This sand had been harvested for centuries for agricultural purpose and proved to have some tin content. This ancillary ropeway is seen in picture 9

Picture 9

Picture 9

There are still remnants of this ropeway to be found. Foundations for some of the pylons still exist amongst the dunes – picture 10 and the ironwork for the anchor point on the beach is still extant – picture 11.

Picture 10

Picture 10

Picture 11

Picture 11

This method, although a massive improvement in terms of the amounts recovered, was not as effective as the management considered it could be and an ambitious scheme was developed to drive a tunnel from the beach to the cliff-top terminus of the aerial ropeway. This would enable wagons full of sand to be pulled to the cliff-top more efficiently than the spur down to the beach for the aerial ropeway and, again, presumably with mining expertise, a tunnel was driven. The beach access to this was through the entrance marked “cave” on picture 4. Its entrance had doors of iron on it for security and was known locally as “Iron Doors”. Picture 12 shows it today with little immediate evidence that it was man-made other than the degraded concrete support that once held one of the doors.

Picture 12

Picture 12

However, the geology of the cliff-face here, plus the fact that part of the cliff profile was actually made of blown sand, ensured that this was a failure. Recent erosion shows the line of this level – picture 13 – and near the top of the cliff and in picture 14 an abandoned wagon can still be seen, waiting for erosion to bring it onto the beach.

Picture 13

Picture 13

Picture 14

Picture 14

With failure of the level up through the cliff, the bottom of the incline was used as a secure place to house the tractors that had been brought to supersede the horse drawn recovery methods. These accessed the beach by an incline built near the treatment works at Godrevy and another from the dunes west of the recovery area. The one at Godrevy, now greatly eroded and used for access to the beach is seen in Picture 15.

Picture 15

Picture 15

That, therefore, outlines the nature of the deposits recovered and the many ingenious ways of getting it to the treatment works. Part 2 will look at the treatment works and give some flesh and colour to some of the people who worked there in its final incarnation.

Cover photo: shows the impact of inland mining at Godrevy and Gwithian

Acknowledgements:

Grateful thanks for the research of Tony Clark, B.Sc., formerly of Camborne School of Mines for his research into the recovery of tin at Gwithian and of the late Robert Cleave, whose meticulous interviews help inform this piece.

David Oates is a Cornish bard who has published a history of Troon, entitled “Echoes of an Age”, a guide to Godrevy and Gwithian, “Walk the hidden ways” and a slim volume of his own verse, “Poems from the far west”. His unpublished work includes a reflection on a Cornish childhood, “What time do they close the gates, Mister?” and a fictionalised story for young people based on the extant life of St Gwinear, with the working title, “The son of a king”. David is working on another guide in the “Walk the hidden ways” series, entitled “Hard Rock country”.

David is a tenor singer with the well-known group, Proper Job based in mid- Cornwall and has collaborated with Portreath musician, Alice Allsworth, to write the lyrics for a number of songs about Cornwall and the Cornish.

Twill be along soon

Hi David – a fascinating read for incomers who associate Gwithian and Godrevy with tourism! Do you know when the tin works closed or how many people worked there? My wife is doing a project on the area focusing on the chalets at Gwithian Towans and how their use has changed over time. We can’t find that date but guess if must have been in the 1940s or 1950s…

Fascinating article. I am not convinced by the the tunnel from the beach to the end of the aerial rope way concept. Recent erosion clearly shows a double fault with mineral intrusion, in the cliff above the “Iron Doors” “Cave” I suggest that this is an old attempt at exploring the fault for minerals, later adapted for access control,or storage.The evidence on the cliff top above the abandoned wagon [Picture 14] reveals the sloping concrete base of some form of silo and an incline to a concrete block with evidence of hold down bolts – presumably the end of the aerial rope way. The direction of the rails on which the wagon appears to sit, suggests that once the sand was hauled up the face of the cliff, it was screened to remove unwanted shingle etc which was deposited into the wagon and

tipped over the cliff back on to the beach. The information board in the Gwithian car park erroneously informs readers that the prewar rope way terminal block was a “Starfish Basket Fire” – part of wartime decoy site to protect Hayle. Such items were always made from “any old iron” not concrete and, for obvious reasons, positioned a long way from the control bunker which is very near by.See Dobinson’s “Fields of Deception” published by English Heritage.

I have walked the dunes from Red River to Hayle and back, with little knowlege of the history of tin recovery. Now that I have read this fascinating and detailed history, I will be walking again with greater enthusiasm. This record was a “Proper Job”. Thank you David.