Two new biographies of the Brontës’ mother Maria and aunt Elizabeth Branwell create divergent impressions of their childhood home and family in Penzance. Neither woman had previously been the subject of an individual biography despite their formative role in the lives of the Brontë sisters. With journalistic flair Sharon Wright sets out Maria Branwell’s literary, religious, romantic, and maternal identities. Nick Holland’s warm appreciation of Elizabeth Branwell sympathetically reveals the character of ‘Aunt Branwell’ who wore whispering silk dresses while clattering around Haworth parsonage with pattens over her shoes.

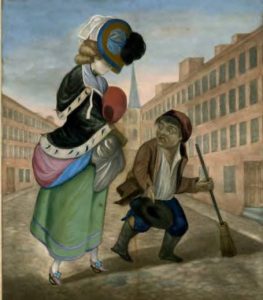

You are clean fair lady but our ways and means are dirty, unknown artist 1791

(shows a woman wearing iron pattens tied onto her fine shoes with blue ribbons).

Thomas Branwell of Penzance

The authors’ opinions diverge in their representations of Elizabeth and Maria’s father Thomas Branwell. Holland’s description of the merchant Thomas Branwell is more Victorian than Georgian in character. His Branwell was a consistently well-established, prosperous man of substance and Methodist who maintained a stolid moral distance from the fisherfolk and smugglers in Penzance who were beset by ‘financial worries and uncertainty’. The Brontës never met their maternal grandfather. Nonetheless as described by Sharon Wright Thomas Branwell might have been the first in a long line of Brontë related or created men with hidden dark, dualistic personalities. An associate of smugglers who resorted to violence even if he was not a pirate.

Neither account of Thomas Branwell is wholly realistic. Thomas Branwell traded and prospered in Georgian Penzance. The second son of a builder Thomas Branwell described himself as an ‘innkeeper’ in 1778 when he insured his inn on the Market Place at Penzance for £500; these premises were identified as the ‘Golden Lion Inn’ in Branwell’s will written 30 years later. Thomas Branwell was a victualler whose trading associates included John Stone the landlord of the Ship and Castle coaching inn on Chapel Street, and his eldest brother Richard Branwell was also an innkeeper who later occupied the Golden Lion.

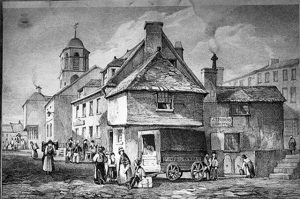

The old market house at Penzance, taken down 1830s. Courtesy Known by Nunn website.

The old market house at Penzance, taken down 1830s. Courtesy Known by Nunn website.

Customs and excise officers made routine checks on traders’ premises and were sometimes successful in bringing prosecutions. The fact that Thomas Branwell’s premises were inspected in 1778 is not therefore evidence that Branwell was suspected of smuggling and on a ‘watch list’ as Wright suggests. Nonetheless in the markets in which Thomas Branwell operated it is difficult to imagine that he would have been as successful as he was if he had not accepted and participated in the exchange of smuggled goods.

In Mount’s Bay smuggling led and organised by merchants was common. In the 1770s merchants including John Coppinger supplied tea imported at L’Orient to British smugglers calling at Roscoff, undercutting imports of the British East India Company. These trading connections were sufficiently strong for Coppinger to move to live in Cornwall from the early 1770s and for British merchants at Roscoff like James Maculloch to sit out the American revolutionary and French wars living in Penzance.

Branwell was a shipowner at a time when ships were the only transportation available to retailers. The shared ownership of ships meant that individual owners could not prevent their fellows completing voyages to which they objected. This was evident in Cornwall in the 1770s when the Quaker surgeon Joseph Fox of Falmouth objected to a trading ship in which he had shares being issued with letters of marque as a privateer. Fox felt so strongly about this that he sent one of his sons to France to find and reimburse the owners of French ships captured by the privateer which had continued to sail with letters of marque despite Fox’s anti-war objections. In 1777-82 Thomas Branwell did not own shares in any of the Mount’s Bay privateers; Branwell was not a Quaker so this suggests that he may have been a risk averse investor or lacked capital due to his family and other commitments at that time. Some Penzance merchants including John and James Dunkin and Richard Oxnam invested in Mount’s Bay privateers which were relatively successful in capturing prizes, and later became substantial shipowners.

Other members of the Branwell family were employed at Penzance in the 1780s-90s as builders, butchers, innkeepers, and mariners including at least one sea captain. Branwell participated in ventures with other Penzance traders including members of his family not all of which were equally successful. These included a construction contract to extend the quay at Penzance in the 1780s when part of the payment was withheld by the Borough while some of the works were redone. In 1785 Branwell insured his premises for £800.

The reduction of duties on tea in 1783 had some impact but salt, silk, spirits, and Russian imports continued to be smuggled in Mount’s Bay. When Henry Boase of Penzance wanted to travel to Britanny in 1785 he found he ‘could pass over by one of our Mount’s Bay boats for nothing’ landing at Roscoff; and in April 1791 when the smuggler Henry Carter sailed in an open boat from Prussia Cove in Mount’s Bay to Roscoff he travelled ‘in company with a merchant who had business there’.

In September 1791 Thomas’ cousin the mariner Captain George Bramwell was named in the notices of wanted men following a confrontation between smugglers and Customs officers off Tresco in the Isles of Scilly in which two revenuemen were killed and others wounded. George Bramwell does not appear to have returned to Cornwall after this incident, and he died as a French prisoner of war in February 1795. The two ships being used by the smugglers the Friendship brigantine and the Liberty sloop were owned by the merchants Jon and James Dunkin with whom Thomas Branwell owned another Penzance registered ship named the Penzance.

Thomas’ sister Jane Branwell and his wife Anne’s cousin the grocer William Carne fostered the Branwell family’s connections with Methodism at Penzance; in 1790 Jane Branwell married the Methodist schoolmaster and lay preacher John Fennel. In the late 1780s merchants and professionals in Cornwall were at the forefront of the campaign to abolish the slave trade which mobilised widespread popular participation including many Methodist and Quaker congregations. The Abolition Society list published in 1787 did not include any Penzance subscribers. Nonetheless in 1791 the Penzance Ladies Book Club purchased Olaudah Equiano’s autobiographical account of his experiences as an enslaved African which persuaded many readers to support abolition. By 1792 a newspaper reported that 12,000 people in Cornwall were supporting the boycott of West Indian sugar and it is likely that this included non-conformist congregations in Penzance.

In 1792 one of the ships owned by Thomas Branwell completed a return voyage to Jamaica. Port records in Jamaica are not extant for that year but it is likely that the ship’s trade was similar to that of the Nancy brigantine in 1787 which carried 642 barrels of pilchards and 5 tons of potatoes from Penzance to Kingston, Jamaica, returning with a cargo of sugar, rum, tamarinds, mahogany, and ‘old copper’. Trade in fish, sugar, rum, and timber was of interest to the Nancy and Betsy’s owners; in addition to Branwell the brigantine was owned by the shopkeeper Lazarus Hart, the fish merchant and cooper Thomas Love, the innkeeper John Stone, and William Woolcock possibly a relation of Thomas Branwell’s brother in law Richard Woolcock.

In 1793 the Nancy and Betsey was lost at sea near Lundy island after leaving St Ives for Swansea. As the revolutionary wars unfolded Branwell did not invest in privateers although in 1795 he purchased shares in a chassemarée named the Liberty; the other owners were Thomas Love and the grocer Barnaby Llloyd. This was not the same vessel as the Liberty sloop which had been impounded by Customs officers at Penzance in September 1791.

Thomas Branwell in 1799.

Thomas Branwell in 1799.

Branwell increasingly prioritised investments in property which were least vulnerable to wartime risks. In 1789 Branwell, who was later a member of the Council, had leased land known as Todman Gear to Penzance Borough on which a school was provided. By 1790 Branwell was a freeholder of land in St Just which qualified him as an elector of the MPs for Cornwall in the same year; he voted for Sir William Lemon and Francis Gregor. He may have inherited property from his father the builder Richard Branwell who died in 1792. By the late 1790s Thomas Branwell was a substantial property owner listed in Penzance land records as freeholder of six houses leased to tenants and the occupier of other premises.

In 1804 when Grace Dennis retired as a draper and grocer after more than twenty years Thomas Branwell was the commercial agent for enquiries from retailers interested in her large shop premises. After Thomas’ son Benjamin married Mary Batten the new partnership of Branwell, Batten and Branwell advertised to recruit a brewer in 1804. Four years later Branwell’s will itemised six dwelling houses let to others, and the Golden Lion Inn on the Market Place occupied by his brother Richard Branwell; plus freehold cellars and premises near Penzance Quay occupied by Branwell himself and John Badcock. It was intended that these properties and related land would generate the £250 annual income needed to pay £50 annuities to his wife and each of his four daughters, while his son Benjamin Carne Branwell was his executor and inherited the remainder. When Thomas Branwell wrote his will only one of his daughters was married; the fact that he stipulated Jane Kingston’s annuity should be free of her husband’s control was common in Cornish will bequests to adult daughters at the time.

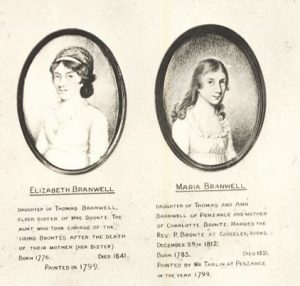

Elizabeth and Maria Branwell

Women worked. Grace Dennis was listed as a mercer at Penzance in a 1790s trade directory in which several other women were listed as grocers, innkeepers, or victuallers. Jane Branwell may have worked alongside Grace Dennis or occupied adjacent premises before she married John Kingston in 1800. Land tax records listed Grace Dennis as holding a joint lease with ‘Mr Fisher’ in 1798 and then with Jane Branwell in 1799. Margaret Branwell’s husband Charles Fisher was a surgeon’s son and bookbinder who became sufficiently well-established as a printer in Penzance by 1797 to recruit an apprentice; he died in 1798. This suggests the intriguing possibility that Jane Branwell briefly occupied Charles Fisher’s printing shop premises after his death, possibly with her sister Margaret; when Jane Branwell later emigrated to America with her family it was printing that her husband John Kingston chose as his new profession in Baltimore.

After John Stone died in 1793 his widow Elizabeth continued to manage the Ship and Castle coaching inn on Chapel Street and later divided her estate equally between her five daughters. As children living on Chapel Street Elizabeth and Maria may have watched people riding pillion and walking to and from the assemblies and plays at the Ship and Castle. Later they went to the Assembly rooms, initially during the time when Elizabeth Stone was managing the premises. Elizabeth and Maria may not have travelled to see ballrooms elsewhere but in 1811 they would have read le Grice’s boast that

Our ball-room too has few compeers;

See, see, those blazing chandeliers!

What music! Ravishing the spheres!

And ah! What pretty little houris

Whose charms are more than ample dowries,

Lightly thread the mazy dance!

Say, say, ye Gods, is this Penzance?

During the French revolutionary wars some merchants at Roscoff like William Clansie moved their families to live in Penzance; where one of his daughters opened a milliner’s shop funded partly by Grace Davy the mother of the famous chemist. In 1799 when the Methodist itinerant preacher Thomas Longley moved from Redruth to Penzance he ‘left [his teenage daughter Martha] at Mr Henry Pearce’s as an Assistance in the shop’. In the early 1800s the novelist and children’s author Eliza Fenwick worked in Thomas Fenwick’s linen draper’s shop on the Market Place in Penzance which also employed two female shop assistants. Information appears to be lacking about occupations of Elizabeth Branwell in 1790–1821 (except for 1815-16 when she was living with her sister Maria’s family in Yorkshire); nor is this information available for Maria Branwell in 1797-1812. Nonetheless Thomas Branwell worked alongside women traders at Penzance, and it is unlikely that as parents the Branwells would have had different expectations of their older and younger daughters in relation to employment.

The men and women who were traders and associates of the Branwell family were not without cultural and literary interests and connections which flourished during the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. The Branwell family miniatures were drawn in 1799 by Mr Tonkin the son of a Penzance grocer and flour dealer who was a keen artist; the occasion for the drawings may have been the wedding of Benjamin Carne Branwell to Mary Batten. The Batten family included the Romantic poet Ann Batten Cristall, her brother the watercolourist Joshua Cristall, her sister Elizabeth some of whose engravings are extant, and her uncle Joseph Batten who lived at Penzance and was a published amateur poet. In 1815 Joseph Batten published an appreciation of Penzance in verse which recognised that Cornish women as well as men were educated

GEOLOGY too, ‘mong all ranks, the trade is,

Beaux are turn’d Chemists, and so are the Ladies

The new terms of Science they learnedly quote,

Sing “Oxygen, Hydrogen, Gas, and Azote.”

(Joseph Batten’s 1815 poem was printed by the Penzance bookseller Thomas Vigurs).

If Elizabeth and Maria Branwell acquired their taste for literary periodicals at Penzance they would have purchased these initially from Mr Hewett, then possibly from Charles Fisher, and later from Thomas Vigurs the son of an innkeeper whose family acquired the Penzance printshop and bookseller’s for their son c.1800. Eliza Fenwick described Thomas’ brother John Vigurs as ‘a tall pleasing young man who reads much, draws well from Nature, & writes agreeable verses’. Mary Love, the wife of Thomas the shipowner, was related by marriage to Charles Valentine Le Grice a published poet who lived in west Cornwall from 1796 who was a friend and correspondent of Charles Lamb since the days when they had both been at Christ’s Hospital School with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Mary Treweeke a widow who was president of the Penzance Ladies Book Club in 1810-12 was the aunt by marriage of Charles Fisher whose mother had been born Grace Treweeke the daughter of the Penzance mayor at the time

Penzance Cornwall, S Fisher & Co 1832. Courtesy Known by Nunn website.

Penzance Cornwall, S Fisher & Co 1832. Courtesy Known by Nunn website.

By the early 1790s Elizabeth Branwell was in her mid teens and would have been more aware of family and other matters than Maria who was seven years’ younger. The real lives of individuals who were associated with the Branwell family at Penzance included some difficult, extraordinary, or tragic experiences.

In 1791 when George Bramwell became a wanted man he was a widower with one daughter, also named Elizabeth and aged 16, who may have looked to other family members including Thomas Branwell for assistance; she later married Thomas Duncan of Paul parish and had four children including a daughter named Grace Poole Duncan. The son of James Dunkin was educated at Penzance grammar school; after his father went on the run William Dunkin was taught long calculation by the vicar of St Hilary and astronomer Malachy Hitchins, and later obtained a job as a ’computer’ for the Nautical Almanac in Truro.

Three generations of West Indian planters lived at Mount’s Bay where John Price was Mayor of Penzance on several occasions, and Sheriff of Cornwall in 1774. The Price family had a house on Chapel Street and at different times occupied the substantial properties of Chywoone, Trevaylor, Kenegie, and lastly Trengwainton the gardens of which are now open to the public through the National Trust. It is possible that Rose Price, who spent three years on his family’s plantations in Jamaica in 1792-5, travelled out on Thomas Branwell’s ship the Nancy and Betsey. In Jamaica Rose Price manumitted Lizette Naish a 13 year old girl described as a ‘quadroon’ with whom he had two children. Price later arranged for their son and daughter to be educated in Britain where Elizabeth married Reverend Alexander Lochore of Dumbarton in Scotland and John Price trained as an engineer before returning to live and work in Jamaica. After returning to Britain Rose Price married a woman of Irish descent named Elizabeth Lambart; they had fourteen children. The family lived in Mount’s Bay where Rose Price was a magistrate, sheriff of Cornwall in 1814, and active participant in educational and cultural organisations including being president of the Penzance library and the Penzance Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge. Sir Rose Price’s will, made and witnessed in Penzance, included annuities for Lizette Naish and Elizabeth Lochore.

In 1803 tragedy struck the Chapel Street home of Lemon Hart the son of the shopkeeper Lazarus Hart who had been one of the owners of the Nancy and Betsey. Lazarus’ daughter in law Letitia Hart received severe burns after a candle set her dress alight; Letitia was pregnant and was delivered of a daughter who lived. Letitia died a few days later of the fatal burns she had received in the fire.

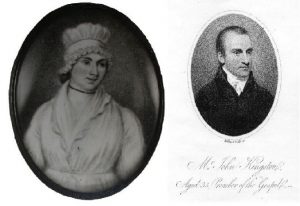

Jane Branwell and John Kingston

Jane Branwell and John Kingston

Elizabeth and Maria’s elder sister Jane Kingston faced marital difficulties. The Kingstons emigrated to America after John Kingston was dismissed as a Methodist minister in 1807. Kingston was expelled by the Methodist Conference following allegations of financial dishonesty and ‘improper behaviour’ with ‘two young men’ in a case which has similarities with others where the disapproved of conduct was sexual. John Kingston was able to start again in America but Jane was unhappy and in 1809 returned to live at Penzance with her baby daughter leaving her other children and their father in Baltimore. Jane Kingston had an independent life in Penzance and may have read her Yorkshire nieces novels and poetry as she lived until 1855.

The Brontë sisters

The Brontë sisters

Maria, the wife and mother from Penzance, who read Byron’s The Corsair never saw her son Branwell’s story The pirate with its lead character the ruthless Rogue. Following the death of Maria Brontë in 1821 as Aunt Branwell cared for her nieces and nephew at Haworth she was said to talk ‘a great deal of her younger days, the gaities of her native town, Penzance in Cornwall’. Elizabeth Branwell had many true stories from Penzance to share. The echoes of which can be seen in the Brontë sisters’ novels. Not least Mr Rochester’s West Indian wife, children outside of marriage, and fatal fire in Jane Eyre.

Note: Nick Holland Aunt Branwell and the Brontë legacy (2018), Sharon Wright The mother of the Brontës (2019). Both biographies are published by Pen and Sword books. With thanks to Peter S. Forsaith for his unpublished research paper ‘”…too indelicate to mention…”: transgressive male sexualities in early Methodism’ .

Cover: Penzance harbour painted from the Dolphin window 1807

Fascinating. Thanks so much for sharing it