There can be no doubt that a unique sense of difference, and, of separateness exists throughout Cornwall. Forged on a history of resistance, Cornwall is strikingly different to its closest regional neighbours across the Tamar. Many people over the years have highlighted a sense of ‘islandness’, using phrases such as ‘almost an island’ or ‘all but an island’. How accurate are these descriptions? Does a special island identity exist? Read on to find out.

Cornwall is quintessentially a maritime region. Almost an island, it is surrounded by water and nowhere in the region is further than twenty-five miles from the sea – most places are a good deal closer. 1

Millennia of fishing, shipbuilding, sailing, smuggling, trading and more recently tourism, have created an inextricable link between Cornwall and the sea, a link that has become an important feature of Cornish identity. Even HRH the Duke of Cornwall recognises the influence of the sea, “Nowhere is far from the sea in Cornwall and, indeed, as is so often said, Cornwall is all but an island. Cornish history has been largely shaped by this maritime environment”.2

Cornwall’s relationship with the sea is unquestionable, the aim of this article is to explore whether Cornwall does share common characteristics with other island communities; namely the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland. Do the terms “almost an island” and “all but an island” accurately describe Cornwall’s geographical, cultural and political landscape?

Geographically, Cornwall displays definite physical island properties; the English Channel and Celtic Sea lie to the North, West and South. Whereas, to the East running almost from coast to coast lies the River Tamar. In geographical terms, Cornwall is almost entirely surrounded by water. However, is this enough to justify the “all but an island” tag? After all, there are numerous peninsular communities with similar natural geographies that lack any notion of an island identity.

There is a misconception in some quarters that island communities are by nature isolated. Recent arguments in the field of Island Studies are focussing on the cultural exchange that takes place between islands and the wider world, suggesting that distinct difference from those around them is only one feature of an island community. Rather they should be judged on how they influence and are influenced by those around them. Adam Grydehøj asserts that “island communities cannot be regarded in isolation as they are fundamentally interconnected with the world around them, their economies rely on the import and export of goods and people, and their cultures are influenced by the inflow of ideas”.

Island communities may play a small role in the wider mainland narrative, yet it is a role that only an island community could play, sufficiently connected to the outside world to exchange ideas, but also sufficiently cut off to maintain its own identity, both in the minds of islanders and outsiders.3

Cornwall certainly ticks those boxes, the natural peninsular geography, coupled with a history of resistance and cultural difference, effectively created a cultural hard border at the Tamar which largely remains to this day. Isolated and insular within the British Isles, Cornwall relied on the sea for trade, migration and cultural exchange with Ireland, Wales, Brittany and the wider world.

The importance of tin as a commodity to the Romans, meant that the Cornish to the far west of the legionary fortress at Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) were largely left to their own devices in exchange for peaceful trade and a steady supply of tin.4 Evidence of small scale Roman/Anglo-Roman occupation has been discovered in Cornwall in the form of a villa at Magor and the forts at Nanstallon, Restormel Castle and Calstock, however, the effects of romanisation are likely to have been minimal. In the centuries following the Roman withdrawal from Britain, the Cornish were faced with a new oppressor – the West Saxons. The West Saxon expansion would result in the Celtic border gradually slipping west, however, it was not until Athelstan set the border at the Tamar in the tenth century that Cornish resistance to the West-Saxons effectively ended.5

Cultural assimilation in the border lands did take place, however, outside of the border regions Cornish culture and language survived, and flourished. Cornwall’s insular history combined with the impact of a successful and established international sea trade, migrations to and from Armorica,6 and the Cornish Diaspora all slot seamlessly into Grydehøj’s argument for the importance of island communities in wider mainland narratives.

Karen Fog Olwig suggests that “to be an islander, is in some ways, to self-identify with difference and with place”,7 something which is considered a key factor in Cornwall’s distinctiveness today. A recent survey posed the ‘Moreno Question’ to a cross-section of Cornish people. 50% identified as only Cornish, 25% as more Cornish than English, and 12.5% as equally Cornish and English. Only a small percentage identified as English or more English than Cornish.8

A similar pattern exists in Orkney and Shetland. Despite a strong local sense of Scandinavian identity in Shetland, few actually identify as Scandinavian, instead the majority see themselves as Shetlanders, or more Shetlander than Scot.9 Similarly, Orcadians self-identify as Orcadian rather than Scottish or Norwegian.10

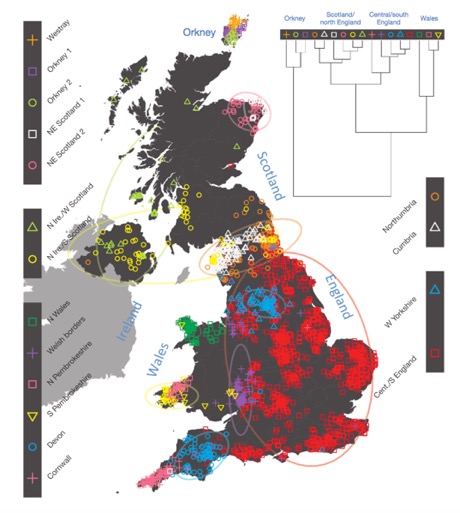

Recent DNA profiling suggests that Norse DNA only accounts for 25% of Orcadian DNA, whereas the strongest DNA presence indicates a pre-Viking, Celtic and Pictish legacy; as well as a post-Viking influence from mainland Scotland.11 The majority of Orcadians and Shetlanders prefer to identify with a constructed Viking identity rather than the more likely Pictish, Celtic or Scots identity. The same study also found that the Tamar represents a marked genetic division between Cornwall and Devon.

Despite this division, the Cornish are genetically much more similar to the people elsewhere in England than they are to those in traditional Celtic nations such as Wales or Ireland.12 Direct resistance to their oppressors (in the case of the Cornish – the West-Saxons and English; and for the Northern Islanders – the mainland Scots), appears to be a driving force in the passionate celebration of Cornwall’s Celtic heritage, and the hybrid non-Scottish identity that exists in Orkney and Shetland.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, Scandinavian culture and language (known locally as Norn) had almost completely disappeared in the Northern Isles. There is no evidence to suggest that islanders identified with their Viking heritage prior to the nineteenth century, largely due to the fact that the islanders lacked a clear idea of who and what the Vikings actually were.

Sir Walter Scott, who had an interest in Norse mythology is largely responsible for the creation of the modern Viking identity in the Northern Isles. Scott’s The Pirate13 presented an overt Viking narrative, that replaced the genuine Early Modern Scots history of Shetland with an imagined Medieval Norse history that was largely of Scott’s own invention.14

Jarlshof – Scott’s invented Norse name for the Scots manor house of Sumburgh – became a symbol of Shetland’s Viking identity, it remains so today as an important tourist attraction.15 Prior to Scott’s romantic Viking revival, anti-Scottish sentiment was already gathering pace. The Scottish were already considered as an ‘other’ by the Shetlanders.

When Scott visited Shetland, he encountered not only a community that had set itself up in opposition to Scotland but also one upon which he could overlay his own Norse historical interests, thereby refining Shetland’s ‘us against them’ concept by portraying the local-outsider culture clash as a conflict of Norse versus Scottish sensibilities.16

Shetland’s ‘us against them’ is closely matched by the Cornish sentiment of ‘burn the bridge’, a clear sign of the desire to remain disconnected and different. Cornwall experienced its own literary and cultural revival in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, however, anti-English sentiment is likely to have existed in some form since the West-Saxon expansion. In contrast to Shetland, Cornwall’s anti-English sentiment has been founded on centuries of oppression and interference. Even today, it could be argued that Westminster’s centralised governance fails to appropriately understand the unique economic, cultural and political situation in Cornwall, or indeed, the needs and wishes of the Cornish people. One example is the disproportionate levels of funding available for national language programmes. The devolved Scottish government’s Gaelic and Scots budget for 2017/18 was in excess of £28m.17 In contrast, the annual budget for the Cornish Language Strategy, which is funded by Cornwall Council, is only £150k. The draft figures for Cornish Language expenditure in 2017/18 highlighted an expected annual spend of £170k.18 Yes, Scotland’s Gaelic and Scots department benefit from their devolved status, however, Cornwall’s comparative level of funding, which comes indirectly from Westminster via Cornwall Council is dispiriting in comparison.

Reverend John Wallis who was Vicar of Bodmin in the mid-19th century vented his frustration at what he saw as the increased centralization of Cornish matters to a London that displayed “a great ignorance of provincial wants and interests”. Rev Wallis continues:

The passing of events and present conditions of our county, should be faithfully recorded, that both ourselves, and those who follow after, may be benefitted by the observations and experience of every succeeding year. Cornwall should be treated as an island. ‘One and All’ is our motto, and every part should take an interest in and contribute to, the improvement of the whole.19

Cornish historians such as Borlase,20 Carew,21 Gilbert,22 Hitchins & Drew,23 and Polwhele,24 all exaggerate the level of Scandinavian interaction with Cornwall between the ninth and eleventh centuries. There is no doubt that some interaction did take place, particularly the battle of Hingston Down in 838, which is recorded in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle.25 However, no evidence exists to support Carew’s or Polwhele’s claims of a Cornu-Viking alliance lasting from 806 to 838. Genuine Latin to English translation error and the incorrect belief that many ancient hill forts were evidence of Danish settlement likely accounts for these erroneous assertions. However, the intentional glorification of a Viking alliance, as an anti-English symbol cannot be discounted.

The presentation of Tintagel as the birthplace of the legendary King Arthur, has resulted in the myth becoming an important symbol of both Celtic and national identity in Cornwall.26 Philip Marsden suggests that Richard of Cornwall’s only motivating factor in building the castle on the site – the ruins of which survive today – was to acquire the legends, stories and sense of place created by the tales in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Brittaniae.27

The Arthurian legend has propelled Tintagel to one of English Heritage’s top five most popular attractions across Britain, and as a result, an extremely important facet of Cornwall’s tourism economy.28 Mythology, landscape, sense of place and isolation are considered important reasons why tourists choose to visit both Cornwall and the Northern Isles. The ruggedness and isolation of the landscapes is directly linked to how locals see themselves and want to be seen by outsiders. The following quote, made recently, indicates the influence of sense of place on identity:

Here too, the Sea, the Sky and the weather dominate. Our culture, our heritage surrounds us, shelters us, and determines who we are. We are Norse, Vikings, people of the North Atlantic. Our Myths are of Norse Gods, trows, giants and Finn Folk. Our Saints are Olaf and Magnus.29

By changing only a small number of key words, the above quote could easily refer to the Cornish:

Here too, the Sea, the Sky and the weather dominate. Our culture, our heritage surrounds us, shelters us, and determines who we are. We are Celtic, Cornish, people surrounded by the sea. Our Myths are of Celtic Gods, mermaids, giants and piskies. Our Saints are St Piran and St Petroc.

Pre-christian mythology and spirituality survives in both communities where it has become an integral part of what makes them different, indeed Piskies and Mermaids are now as inextricably linked to the Celtic past,30 as Trows and Finn Folk are in Orkney. The similarities between Cornish and Orcadian mythology are undeniable. Kevin Crosselly-Holland notes that Norse mythology was influenced by Celtic mythology, possibly as a result of Hiberno-Norse interactions.31 If so, it is entirely possible that the exchange of knowledge between Celtic communities and Orkney resulted in spiritual and mythological exchange also.

Landscape and sense of place have clearly had a huge influence on Cornwall, Shetland and Orkney, as has their relationship with the sea. Connection with romanticized pasts are an important feature of self-identify.

Henry Jenner and Robert Morton Nance are considered key figures in the revival of the Cornish language. However, there is evidence to suggest that their work built on earlier developments dating back to the late 19th century which were lead by figures such as Rev W.S. Lach-Szyrma. Peter Beresford Ellis suggests that the reawakening of the Cornish Language directly influenced a new sense of Cornish nationhood in the 1930s.32 Samantha Rayne asserts that the revivalist work conducted by Jenner, Nance and their contemporaries created “a sense of homogenous uniqueness that was so valuable to the community as a whole that its preservation was seen as vital and therefore must be defended”.33 The notions of uniqueness and difference that are felt throughout Cornwall and the Northern Isles are as much a result of their cultural revivals, as their physical island geography.

The 2014 Scottish independence referendum led to calls among Shetlanders and Orcadians to hold their own independence referendum.34 However, resistance to centralized government certainly wasn’t a new phenomenon, it has been an almost constant theme since Norway gifted the islands to Scotland in the fifteenth century. Similar trends exist in Cornwall, recently, pro-nationalist movements have used Cornwall’s Stannary history, and the recent recognition of Cornish people as an official minority to push claims for independence and devolution.35

Similarities also exist in the Liberal politics of Cornwall and the Northern Isles. Cornish politics was dominated by the Lib-Dems and Conservatives between 1959 and 2010, with the Liberals enjoying success between 1992 and 2010.36 Orkney and Shetland have been exclusively Liberal since 1950.37 The pro-devolution Orkney and Shetland Movement, attempted to break the Liberal strangle-hold during the 1980s, but were ultimately unsuccessful.

There are clear and obvious similarities between Cornwall, Orkney and Shetland, however, this alone does not account for Cornwall’s apparent island identity. Tourism is crucial to Cornwall’s economy. Worth in the region of £1.8 billion annually,38 it is understandable that marketers may face pressure to use all of the weapons in their arsenal, the notion of separation and difference proving an important tool in achieving their aims.

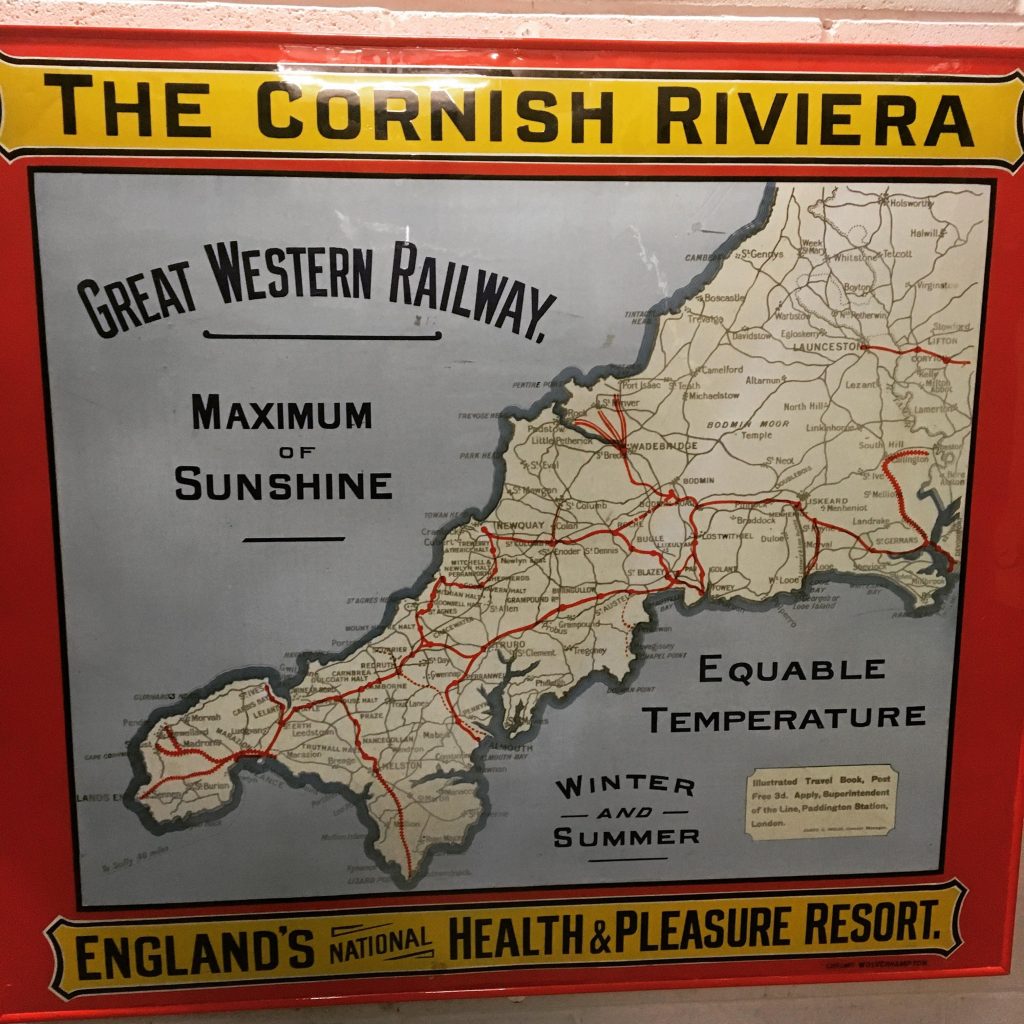

Great Western Railway (GWR) relied heavily on exaggerated and imagined Cornish geographies in their marketing campaigns of the early 20thcentury. Namely, their promotion of the ‘Cornish Riviera’ as a major tourist destination. Chris Thomas argues that the material effect of GWR’s advertising and marketing campaigns did not merely reflect an external reality, but selective and partial re-representations of it. Cornwall was marketed as having the maximum of sunshine, health benefits, and as sharing many characteristics with Italy.39

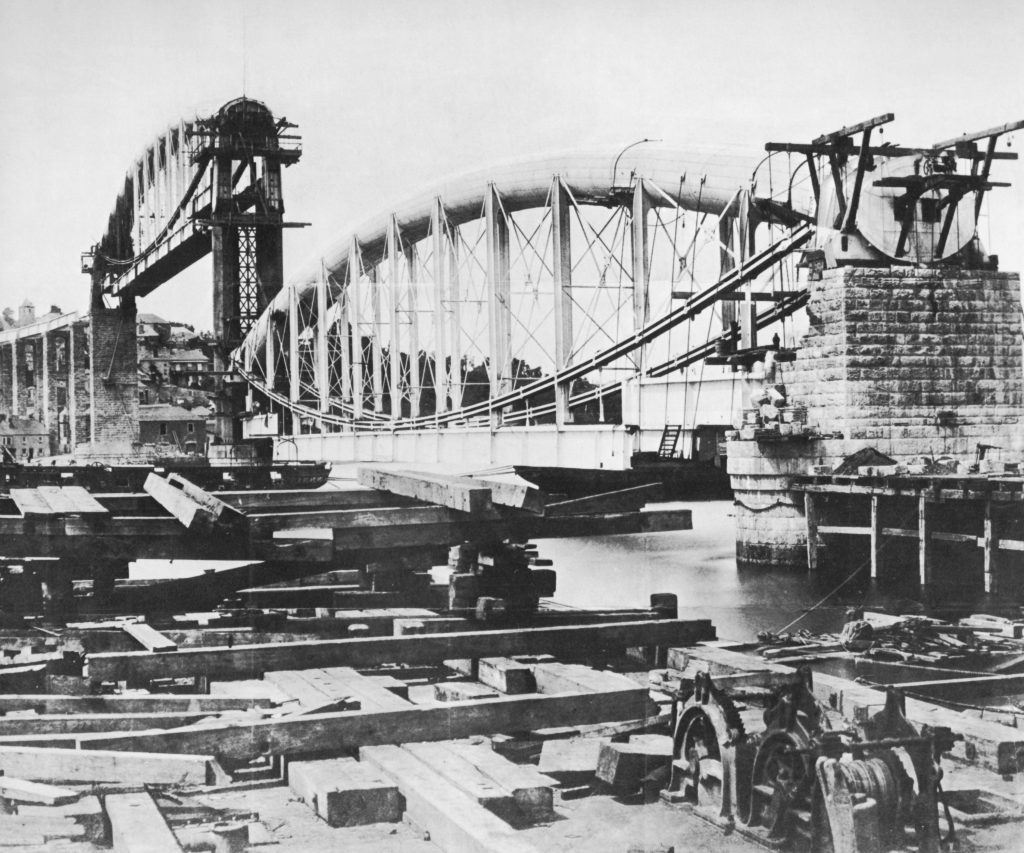

The opening of Brunel’s Royal Albert rail bridge across the Tamar in 1859 created a new link between Cornwall and the rest of the UK. The first train ran between Plymouth and Truro on 11 April 1859, FE Halliday nicely sums up the huge effect that the bridge had on Cornwall’s previously isolated nature.

Cornwall was no longer all but an island, remote and inaccessible. A few years before, a journey from Truro to London was the event of a lifetime experienced by very few Cornishmen, and very few Englishmen penetrated far beyond the Tamar; but now […] the far west [was] within a few hours of the great cities of the east and north.40

Chris Thomas uses the phrase “making Cornwall possible”, in his assertion that it was “GWR and railways that made Cornwall possible for much of the British population.”41 This opening of Cornwall to the rest of Britain calls Cornwall’s islandness into question. There is no doubt that the Royal Albert rail bridge, and later, the Tamar road bridge brought with them a feeling that Cornwall was being drawn to the mainland. Sea trade was increasingly being landed and transported out of Cornwall by rail and later by road.

The advent of steam put paid to Falmouth’s packet ships, the ways of old were slowly disappearing. However, in my opinion it is exactly this modernisation that has allowed Cornwall and its people to see itself as distinctly different from those across the Tamar. Awareness of difference is difficult without exposure to those who are different. Modernisation has brought advances in communication and travel which have made Cornwall more accessible, this has undoubtedly eroded part of Cornwall’s geographic sense of islandness. There can be no doubt however, that symbolically and culturally, Cornwall retained its own distinct island identity. After all, the Northern Isles have themselves been modernised to the point that you can fly from Edinburgh to Kirkwall, Orkney in 75 minutes, a mere five minutes more than it takes to fly from London to Newquay. It is Orkney’s culture, spirituality, sense of place and distinct differences with those around them that truly defines it as an island. It is quite clear that those same parameters also apply to Cornwall.

Isolated and insular, yet interconnected with the wider world, Cornwall, like the Northern Isles has used the sea to extend its influence far beyond its physical reach, and in the case of the Cornish Diaspora, to every corner of the globe. Further similarities exist in politics and spirituality that are likely a direct consequence of their shared characteristics. However, in my opinion it is the effect of their own cultural revivals that has shaped their modern identities. A modern identity that has proven useful in tourist branding and marketing to the extent that Cornwall’s identity is being further re-imagined. Due to the Tamar falling a few miles short of the North Coast, geographically Cornwall could be said to be ‘almost an island’. However, in almost every other sense, Cornwall displays a distinct identity that has a lot more in common with the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland than its neighbours across the Tamar.

Title image (c) hobgobgraphics, Penzance. Thank you to all at hobgobgraphics for allowing us to use their image.

Bibliography

- P. Payton, A. Kennerley and H. Doe (eds.), The Maritime History of Cornwall, (Exeter, 2014), pp. 12-16.

- Ibid, foreword by HRH The Duke of Cornwall.

- A. Grydehøj, ‘Ethnicity and the origins of local identity in Shetland’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, Vol 2, Issue 1, (Jun., 2013), pp. 39-48.

- M. Todd, The South West to AD1000, (New York, 1987), pp. 192-95.

- B. Deacon, Cornwall: A Concise History (Cardiff, 2007), pp. 4-5.

- Armorica was a region of Gaul that roughly corresponds to the Brittany of today. Due to the large level of migration between Cornwall and Armorica, there are many cultural similarities that survive to the present day, such as language and family names.

- K.F. Olwig, ‘Islands as places of being and belonging’, Geography Review, Vol 97, Issue 2, (2007), pp. 260-273.

- P. Woodcock, ‘Cornwall and Yorkshire show regional identities run deep in England too’, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/cornwall-and-yorkshire-show-regional-identities-run-deep-in-england-too-41322 (last accessed 24 March 2018).

- A. Grydehøj, ‘Ethnicity and the origins of local identity in Shetland’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, Vol 2, Issue 1, (Jun., 2013), pp. 39-48.

- M. Jones, ‘Playing the indigenous card? The Shetland and Orkney Udal Law group and indigenous rights’ Geo Journal, Vol 77, Issue 6, (Dec., 2012), pp. 765-75.

- ‘Orkney people: study finds strong pre-Viking DNA’, BBC News Online, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-31946436 (last accessed 25 March 2018).

- B. Leslie, et al, ‘The fine scale genetic structure of the British population’, Nature International Journal of Science, http://www.nature.com/articles/nature14230 (last accessed 26 March 2018).

- Sir Walter Scott, The Pirate, (Edinburgh, 1822).

- A. Grydehøj, ‘Ethnicity and the origins of local identity in Shetland’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, Vol 2, Issue 1, (Jun., 2013), pp. 39-48.

- ‘Jarlshof Prehistoric and Norse Settlement’, Historic Environment Scotland, https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/jarlshof-prehistoric-and-norse-settlement/history/(last accessed 27 March 2018).

- A. Grydehøj, ‘Ethnicity and the origins of local identity in Shetland’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, Vol 2, Issue 1, (Jun., 2013), pp. 39-48.

- Scottish Government’s Gaelic department Budget FOI release, https://www.gov.scot/publications/foi-17-02147/(last accessed 7 November 2018)

- Cornish Language Strategy Operational Plan 2017/18 – End of Year Report, https://www.cornwall.gov.uk/media/33544265/cornish-language-operational-plan-2017-18-end-of-year-report-mar-18.pdf (last accessed 7 November 2018)

- J. Wallis, The Cornwall Register (Bodmin, 1847), pp. 122-125.

- W. Borlase, Observations on the Antiquities, Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall, (Oxford, 1754), pp. 44-47.

- R. Carew, The Survey of Cornwall, (London, 1811), p. 273.

- C.S. Gilbert, An Historical Survey of the County of Cornwall, (Plymouth, 1817), p. 291.

- F. Hitchins & S. Drew (eds.), The History of Cornwall from the Earliest Records and Traditions, to the Present Time, (Helston, 1824),pp. 404-6.

- R. Polwhele, The History of Cornwall: Civil, Military, Religious, Architectural, Agricultural, Commercial, Biographical, and Miscellaneous,Vol 2, (Plymouth, 1816), pp. 12-13.

- M. Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (London, 2003), p.62.

- E.G. Proctor, ‘The Legendary King: How the Figure of King Arthur Shaped a National Identity and the Field of Archaeology in Britain’, published thesis, University of Maine, (2017), pp. 2-5.

- P. Marsden, Rising Ground: The search for the spirit of place, (London, 2015), pp. 82-86.

- E.G. Proctor, ‘The Legendary King: How the Figure of King Arthur Shaped a National Identity and the Field of Archaeology in Britain’, published thesis, University of Maine, (2017), pp. 42-44.

- A. Grydehøj, ‘Ethnicity and the origins of local identity in Shetland’, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, Vol 2, Issue 1, (Jun., 2013), pp. 39-48.

- P. Beresford-Ellis, Celtic Myths and Legends, (London, 2002), pp. 257-65 & 475-85.

- K. Crossley-Holland, ‘Norse Myths: Gods of the Vikings’, (London, 1993), pp. 188-91.

- P. Beresford-Ellis, The Celtic Revolution, A Study in Anti-Imperialism, (Ceredigion, 2000), pp. 40-45.

- S. Rayne, ‘Henry Jenner and the Celtic Revival in Cornwall’, published PHD thesis, University of Exeter, (2012), pp. 18-20.

- ‘Will Orkney and Shetland join the Micronationalists?’, The Guardian Online, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/shortcuts/2014/mar/24/will-orkney-shetland-join-micronationalists-independence-vote(last accessed 27 March 2018).

- ‘Cornish Identity: Why Cornwall has always been a separate place’, The Guardian Online, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/apr/26/survival-of-cornish-identity-cornwall-separate-place(last accessed 28 March 2018).

- ‘Kernowpolitico: Notes from the periphery’, https://www.psephologyfromtheperiphery.wordpress.com/category/cornish-politics/(last accessed 28 March 2018).

- ‘Candidates and Constituency Assessments: Orkney and Shetland’, Alba News, https://web.archive.org/web/20120118141216/http://www.alba.org.uk/scot99constit/h05.html(last accessed 28 March 2018).

- Andrew Wallis, ‘The blog of a Cornwall Councillor for Porthleven and Helston West’, http://www.cllrandrewwallis.co.uk/tourism-and-its-impact-on-cornwalls-economy/(last accessed 28 March 2018).

- C. Thomas., ‘See Your Own Country First: the geography of a railway landscape’ in E. Westland (ed.), Cornwall: The Cultural Construction of Place, (Penzance, 1997), pp. 107-11.

- F.E Halliday, A History of Cornwall, (2009, Cornwall). pp. 321-324.

- C. Thomas., ‘See Your Own Country First: the geography of a railway landscape’ in E. Westland (ed.), Cornwall: The Cultural Construction of Place, (Penzance, 1997), pp. 107-11.

Well done! Nice, thoughtful essay and great comparative work. A typo that causes confusion – shoot me an email if you wish. I rather not burden this comment with that sort of thing. Really enjoy your work here.

Thanks very much, it slipped through the net, but I found it. Take care