Lime kilns are an important part of our industrial history and most Cornish coastal or river communities would have had at least one with the resultant product used locally. They were mostly stone structures and their purpose was to convert limestone to quicklime, mainly for the construction and agricultural industries. It is difficult to be precise about their antiquity but their period of use is likely to be from the 16th to the early 20th century. The process of burning lime has taken place for thousands of years and our ancestors were well aware of the mineral’s qualities.

This list of lime kiln locations appeared on the Internet: it is certainly not a complete record (I have read one comment that there were in excess of 230 in Cornwall) but it does serve to indicate that they were a common feature in our communities.

Bohetherick Quay, Boscastle, Calstock Quay, Charlestown kiln 1, Charlestown kiln 2, Cotehele Quay 1, Cotehele Quay 2, Cuddenbeak Quay, Danescoombe Quay, Devoran, East Portholland, Forder, Foss Millbrook, Golant, Gorran Haven, Halton Quay, Highercliff, Higher Pier Millbrook, Higher Quay Tideford, Kelly Road, Kilhallon, Kilna Park, Kilna Quay, Lamorna Cove, Lerryn kiln 1. Lerryn kiln 2, Lostwithiel kiln 1, Lostwithiel kiln 2, Lostwithiel kiln 3, Milltown, Moorswater B, Moorswater C, Netstakes Kiln 1 Gunnislake. Netstakes kiln 2 Gunnislake, Newbridge Gunnislake, Newquay, Okel Tor, Pendower, Penpoll, Perran River (Norway Inn), Polbathic, Polkerris, Pont kiln A, Pont Kiln B, Port Gaverne, Porthleven, Porth Newquay, Portloe, Readymoney Cove, Roche, Rough Torr Barn, Roundwood, Sandplace kiln 1, Sandplace kiln 2, Sconnor, Shallowpool, St German’s Quay, St John’s Ford, St Keyne, Treath, Trelew, Mylor Creek, Wearde Quay, WEst Portholland.

Boscastle Lime Kiln (Photos: Tony Mansell)

Boscastle Lime Kiln (Photos: Tony Mansell)

Heritage Gateway refer to this as a lime kiln at the east end of Boscastle harbour in the parish of Forrabury and Minster. Its Grid Reference is SX 0979 9133 and it dates to the late 18th century. It is described as being “constructed of slatestone rubble and calcareous spar. Square-on-plan, and built into the side of steeply sloping bank with a round arched opening on the south. It states that the limekiln has a round arched opening in the right-hand side wall but that the left-hand opening was obscured by the addition of a block of lavatories built in the 1970s. It originally had access from raised ground to the rear to enable top loading.

A structure is shown in this position on the Forrabury tithe map (1842) and most probably represents the lime kiln. It was recorded as disused, with the adjacent lime house, in the Boscastle Manor estate sale particulars of 1884 and marked ‘Old Limekiln’ on the 2nd Ed OS 1:2500 map (c 1907). A lease agreement of 1910 (Knight collection) refers to public conveniences attached to the kiln, although those on the west side prior to the floods are likely to represent a later twentieth century rebuild.

The kiln ‘pot’ would originally have been charged with lime and culm drawn on carts up the ramp rising immediately to the east; the burnt lime was removed via the arched opening at ground level on the south. The position of the kiln, close to both a landing point for lime and culm brought by sea and to road routes inland resembles both that of the other kiln on the south side of the harbour and of many other kilns around the Cornish coast.” The report concludes by saying that the stonework of the kiln appears to be in good condition.

Charlestown Lime Kilns. The three-hearth dockside kiln is still there but the roundhouse sits on top of the basement. The other photo is the kilns below the boathouse restaurant just below and opposite the Rashleigh Arms. (Photos: courtesy Lyndon Allen)

Charlestown Lime Kilns. The three-hearth dockside kiln is still there but the roundhouse sits on top of the basement. The other photo is the kilns below the boathouse restaurant just below and opposite the Rashleigh Arms. (Photos: courtesy Lyndon Allen)

Heritage Gateway refer to Charlestown Harbour Lime Kiln which is next to the site of the bath house on Charlestown outer harbour (Grid Reference is SX 0394 5153) “the eye of the kiln is obscured by a lean-to shed used as a fishing store but, it states, a local resident, recently deceased, remembers the kiln in action, and the bath house next to it served the workers.”

Heritage Gateway refers to two other Charlestown Lime Kilns (Grid Reference: SX 0378 5171) as having arches visible from the adjoining pottery shop and being obviously from different phases of construction. It states that “the north kiln is constructed of blue slate, whilst the more recent south kiln is constructed from large granite blocks and lined with brick. Because the arches have been blocked some time ago, it is not possible to assess the condition of the pots.”

Heritage Gateway refer to yet more kilns and cellars in the centre of Charlestown (Grid Reference: SX 0376 5171 Listed Building No. 4/10001). It states that the “1825 map shows three kilns in an unusual arrangement, being one kiln to the west within a parapeted structure, and another two kilns in a similar parapeted structure to the east. The field evidence indicates that the lime kiln complex originated as a back-to-back arrangement of two kilns, with a third kiln added to the front of the eastern one. The two original kilns are built of rubble masonry, whilst the third kiln is built of substantial granite blocks and has a brick arch. Map evidence indicates that the site had already been extended before 1825 and that another building occupied the space to the south of the kilns. These kilns are built into the slope and were loaded from the top. A former yard for the storage of limestone and culm (a poor-quality coal used for firing) was situated north of the kilns. Burnt lime was removed from the kilns from arched openings at the bottom and was used as fertiliser as well as lime mortar and lime wash. The arrangement for this at Charlestown is not easily seen, as the inner part of the back-to-back kilns is now infilled, and the site is partially enclosed by other buildings. A tunnel with a mouth at the south-western corner of the site may have provided access to the innermost kiln arches and was used for lighting the kilns. A small round brick chimney-like structure beside the eastern kiln may have been a vent linked to the tunnel and the centre of the back-to-back kilns. The kilns are probably now infilled or capped and their tops cannot be seen due to paving and vegetation.”

One of four lime kilns at Lerryn

One of four lime kilns at Lerryn

Heritage Gateway refers to it as a disused lime kiln built during the early 19th century and heightened by the mid-19th century. Its Grid Reference is SX 1403 5701 and it is in the parish of St Veep. “According to its Listing description, it is constructed from rubblestone with large quoins and cut stone round arches to openings to the north-east and south west. It is rectangular in plan with a flat top, recently converted to a seating area, and was built into the side of a steep slope in order to facilitate top loading. The north-east arch affords access to the brick lined rubblestone shaft.”

Pendower Lime Kiln (Photo: Jai Beetham)

Pendower Lime Kiln (Photo: Jai Beetham)

An advert for the sale of Pendower Lime Kiln:

1823: To be disposed of, by private contract, a respectable business, in the above line, at Pendower Beach, in the parish of Philleigh; where the trade in lime and coal has been for some years established, and is now carried on to a considerable extent. 1

Heritage Gateway records a tragic accident here in 1819 which claimed two lives. Its Grid Reference is SW 8968 3816 and it is described as being in poor condition.

It states: “When offered for sale in 1823, it was claimed that ‘The trade in lime and coal has been some years established and is now carried on to a considerable extent’. The kiln was in good condition, although used as a pigsty, until 1955 when it was damaged by a storm, and is falling into serious disrepair. Pendower Beach is a local source of limestone.”

Terras Bridge and Lodge near Looe 1870s showing limekiln (Photo: courtesy Malcolm Mc Carthy)

Terras Bridge and Lodge near Looe 1870s showing limekiln (Photo: courtesy Malcolm Mc Carthy)

Limekiln on West Looe River (Photo: courtesy Malcolm Mc Carthy)

Limekiln on West Looe River (Photo: courtesy Malcolm Mc Carthy)

Pont Lime Kiln (Photo: courtesy Lyndon Allen)

Pont Lime Kiln (Photo: courtesy Lyndon Allen)

Pont Lime Kiln A (Photo: Tony Mansell)

Pont Lime Kiln A (Photo: Tony Mansell)

Heritage Gateway states that this is the larger of two lime kilns at Pont (Grid Reference SX 1431 5183 in the parish of Lanteglos). It is described as “A lime kiln marked at the location on the Tithe Award. By 1907 it was disused. It is still extant. In 1839 it was in the possession of John Hicks. The building date of the kiln is unclear, but it may be before 1816 when Tredudwell Farm was on the market, advertised as ‘near a sanding cove and lime kiln’; likely to refer to Pont and Lantivet Bay. Its future is assured, as it is under the ownership of the National Trust.”

Porthleven Lime Kiln (Photos: Tony Mansell)

Porthleven Lime Kiln (Photos: Tony Mansell)

This Porthleven lime kiln was erected circa 1814 alongside Breageside Wharf. In 1816, 184 tons of Plymouth limestone were delivered to the harbour. Harvey & Co of Hayle took over the harbour in 1853 and also developed the trade from the kiln. In 1870, 895 tons of stone was burned and this continued into the 20th century. It finally ceased to be used in 1920. The kiln is unusual in Cornwall as it is round in shape and has flat lintels. They were all based on the simple draw type kiln in which the fuel and limestone are placed in the kiln in alternate layers. As the fire moves up, the kiln burnt lime is drawn out at the bottom.

Heritage Gateway describe it as a circular kiln still extant near Porthleven harbour (Grid Reference SW 6278 2569) It is shown as a limekiln on the Tithe Map of 1840 and on the 1st Edition 1:2500 OS map. It was extant in 1811 when it was owned by Tobias Roberts. It is probably the best documented kiln in the county and is noted by Sheppard in 1977 as being in good condition with its ramp still complete.

Porthpean Lime Kiln in 1869 from the main road. You can see the slipway railings to the right, this leads down to the beach. The limekiln was situated to the west of the fish cellars and malthouses. (Photo: courtesy Lyndon Allen)

Porthpean Lime Kiln in 1869 from the main road. You can see the slipway railings to the right, this leads down to the beach. The limekiln was situated to the west of the fish cellars and malthouses. (Photo: courtesy Lyndon Allen)

Heritage Gateway states that one lime kiln was marked on the Tithe Award maps at Porthpean in 1840, and the 1st Edition 1:2500 OS map (Grid Reference: SX 0313 5061) but it is not extant.

Readymoney Cove Lime Kiln

Readymoney Cove Lime Kiln

The Cornish Guardian of Thursday the 30th June 1955 reported that Mr Jesse Julian, a former mayor of Fowey, presented the lime-kiln at Readymoney to the Borough in memory of his father. It is now a pleasant vantage point overlooking the mouth of the river and the woods at St Catherine’s Point.

Heritage Gateway states that the kiln (Grid Reference SX 1179 5110) was founded by William Rashleigh in 1819, after work was delayed in 1810 by a protest from the public when building equipment was thrown into the kiln and smashed, causing damage to the fabric of the kiln. It was restored in 1935 for the Silver Jubilee of George V. It adds: “Good survival of early C19 lime kiln structure with additional ornamentation for use as a folly.”

To finish this little selection, here’s one requiring information. Do you know where it is? (Photo: courtesy Malcolm Mc Carthy)

To finish this little selection, here’s one requiring information. Do you know where it is? (Photo: courtesy Malcolm Mc Carthy)

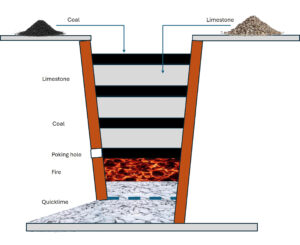

The Process

A simplified sketch of an operating lime kiln (Tony Mansell)

A simplified sketch of an operating lime kiln (Tony Mansell)

The objective was to convert the limestone (calcium carbonate) into a usable material (calcium oxide – quicklime or burnt lime) by subjecting it to high temperatures (burning) in a confined space (the kiln).

Prior to a ‘burn,’2 a fire of wood and coal was built at the base of the empty kiln and the ‘lime burners’3 shovelled in the first few layers of coal and limestone.

The fire was then lit and the ‘burning’ was underway reaching temperatures in excess of 900 degrees centigrade. The lime burners continued to add more stone and coal until the kiln was eventually full of burnt lime. Depending on the size of the kiln, burning could continue for two to four days and this was followed by perhaps two days of cooling.

Once burnt, the quicklime was shovelled into barrels or carts and taken away for crushing.

In many cases, kilns were built ‘against the country’4 to provide support on one or more sides and easy loading from the higher side but there was no common design and construction was often determined by the individual site.

Some natural limestone was available from Cornish quarries but most of it arrived by sea and river. The boats would run up the beach on a rising tide to get as close as possible to the kiln. The stone was thrown overboard, loaded into carts and deposited by the kiln where it was broken up and stored under a makeshift roof to help keep it dry. Meanwhile, the boat was floated off on the same tide if possible.

The other essential element was coal or culm (a poor grade coal)5 which was used to burn the limestone. It was imported by ship – from South Wales or elsewhere – which often beached at high tide so that the cargoes could be transferred to carts which conveyed it to the kiln.

As with every industry and workplace, these kilns were a source of danger and there are many instances of accidents and deaths attributed to their use. The fumes given off were noxious and there was always the danger from the fire. This applied to the lime burners who earned their living from them, the folk who lived near them and the occasional tramp or homeless person who, on a cold winter night, was attracted to a warm location.

The following newspaper reports are just a sample:

“On Wednesday last, an inquest was held by John Carylon, Esq., at Devoran, on the body of Nicholas Scobell, 28 years of age, who was found dead in a lime kiln there, belonging to Mr Michell. The deceased was one of Kea Parish, and has not been able to gain his livelihood by work since he met with an accident, about two years ago. How he had supported himself during that period seemed very doubtful, but Mr Michell’s lime burner deposed that he had frequently found him on the kiln when he had gone there to work early of a morning. On Wednesday morning he went there to work about six o’clock, and found the deceased in the kiln quite dead. The fire had not reached the surface of the kiln, and the deceased did not appear to be burnt. He was suffocated – Verdict accordingly.” 6

“A Man Baked to Death. An accident of a shocking character, and by which a man named John Rees met with a dreadful death, has occurred at Mountain Ash, Glamorganshire. In the neighbourhood are some Kilns for the manufacture of Lime, at one of which the deceased, who was a steady, well-conducted man of between 30 and 40 years of age was engaged, when he accidentally slipped through the crust into the burning kiln. His cries brought help, and strenuous efforts were made in the hope of extricating him from the appalling situation in which he was, but unhappily, they proved unsuccessful and the poor fellow was slowly burnt to death in the kiln. His charred and mutilated body was ultimately got out, and information having been forwarded to the coroner … From the evidence produced, it appeared that the death was entirely to be attributed to an accidental cause, and the jury returned a verdict to that effect. The deceased was much respected in the circle in which he moved, and his horrible death has caused quite a gloomy sensation in the neighbourhood.”7

“Devoran Shocking Fatality. At Devoran on Monday night William Bishop, a porter on the quays, met with a shocking death. Deceased, who had no fixed abode, often slept near the lime kiln belonging to R T Michell and Co. It is supposed that on the night in question he went to his usual quarters, and in order to obtain warmth, stretched himself along the top of the kiln. Doubtless the fumes arising from the burning lime rendered him unconscious, and on the fire increasing he was fearfully burnt. His face and head were almost burnt to a stump, his right arm was entirely gone, and on the body being removed from the kiln, the left arm dropped off. William Curnow, the workman, on going to the kiln next morning about seven o’clock, made the shocking discovery. He at once obtained assistance, and gave information to P.C. Bennetts. The body was removed to a shed belonging to Mr William Stevens, carpenter. Deceased was a young man of rather eccentric habits, and had no relatives residing in the village. At the inquest on Tuesday a verdict of ‘Accidental death’ was returned.”8

On a lighter note, this comment appeared in the Butte Tribune Review:

“The way to cook a 14 years old gander is to touch off a couple of sticks of dynamite in his innards to loosen up the joints, and then fry him in a lime kiln.”9

Traditional Uses of Lime

Lime was once much more common in the construction process than it is now but the widespread use of cement led to a huge reduction in its use and contributed to the demise of the traditional lime kilns scattered across the country.

Cement is a much harder material and essential for use in concrete and other purposes but slaked quicklime, (calcium hydroxide) makes an ideal material for mortar and plaster. It allows structures to breathe in a way cement never can and significantly reduces the opportunities for damp penetration. It is softer and more malleable (easily worked), and cures more slowly giving time to work it before it sets, and I have heard it said that it is a joy to work with.

Limewash, often referred to as ‘whitewash,’ was a lime and water mixture for painting walls and fences. It was used for aesthetic purposes and to provide protection from the weather. Eventually, some form of colouring agent was added giving rise to the old Cornish joke when the painter asked his boss, “What colour we gonna whitewash ‘n Cap’n.”

Other industries benefitted from the use of lime – not least agriculture and there are records from as long ago as the 13th century giving permission to use lime-rich sand from beaches to improve the quality of Cornwall’s acidic soil. Even into the 20th century it was a common sight to see carriers with their horse and carts on our beaches loading sand for transportation to inland farms where it was used to spread on the fields. Sand from the coastal area at Bude is unusually rich in minerals, and the poor agricultural land of the locality was found to benefit considerably from application of the lime-bearing sand. Distance was always a problem on the lanes of Cornwall and in the early 19th century the Bude canal was built to transport it inland.

Geoff Osborne, a director of Teagle Machinery Ltd, refers here to its use in its unslaked state. “The quicklime was used as a dressing on fields to reduce the acidity of the soil. As farmyard manure is applied to fields, so the soil tends to become more acid, which makes it less fertile for many crops. This situation is rectified by the application of suitable quantities of lime using a lime spreader. The pictures below show a couple of examples – the self-propelled type which is unusual in the UK, and the towed type which are the most common.”

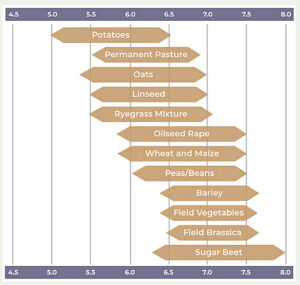

Geoff continued, “Lime is traditionally supplied in powder form, which is difficult to spread and does not flow through a normal fertiliser spreader. Lime spreaders have a sort of conveyor in the base of the hopper, which takes the powder to the back of the machine and drops it onto one or two rotating discs to be spread. In recent years, lime has become available in a granular form, which makes it look a bit like fertiliser. Because it is granular, it flows reasonably well and can be spread using a normal mounted fertiliser spreader. This is a convenient way of applying lime to smaller acreages but the raw material is more expensive than bulk powdered lime. A farmer would not normally own a lime spreader – he would hire a contractor to do it. These days, a farmer would normally have some field soil samples tested to determine the pH level10 and from this he would be able to decide how much lime is needed (if any). The diagram below shows optimal Ph values for different crops.”

A table showing Optimum pH for Crop Growth (Source: St Catherine’s Seeds)

A table showing Optimum pH for Crop Growth (Source: St Catherine’s Seeds)

This website, https://www.stcatherinesseeds.co.uk/lime-distributors/, and others, provides information on the use of lime. It claims that unless steps are taken to maintain the soil’s pH there will be a natural increase in the acidity and a reduction in soil fertility.

It suggests that losses occur as a result of rainfall (causing leaching), cropping, grazing and fertiliser and manure use and that that lime is essential for yields in that it maximises fertiliser inputs, improves stock health, improves soil structure and increases herbicide efficiency.

The Demise of the Local Lime Kiln

Lime burning has been undertaken since Roman times and the lime produced certainly sounds like a wonder material. So much so that its use is still essential in many industries including construction and agriculture. But, and it is a big but, it is no longer produced in local lime kilns. These structures, like the old tin burning houses, were ‘of an age’. They served their purpose and as the process became centralised into large industrial kilns and as transportation improved, these once essential structures were no longer needed.

So, the old kilns still stand guard near our harbours and on river sites, but they are no longer involved in the production of processed lime. They exist simply as a relic of our industrial past and to provide a questioning point for our visitors to whom they are of passing interest as they ask, “I wonder what they were used for?”

Endnotes:

- From the West Briton of 19th December 1823

- A burn is the process of applying heat to convert lime into quicklime.

- A burner is a worker who operates a lime kiln.

- Against the country is a Cornish term for a building erected tight to the face of a bank.

- Culm is a poor grade coal.

- From the Penzance Gazette of Wednesday 6th April 1842

- From the Royal Cornwall Gazette of Friday 12th April 1861

- From the Cornish Echo and Falmouth & Penryn Times of Saturday 30th January 1892

- From the Cornishman of Thursday 10th January 1901

- pH is a measure of acidity/alkalinity of soil.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history, is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and co-editor of Cornish Story.

A very interesting article.

My great grandfather, John Phillips, was a lime burner. In 1861 aged 26, he is listed as such when he lived at Burnthouse St Gluvias (on the road from Penryn to Ponsanooth). Not sure at which limekiln that would have been.

By 1881, he had moved to Devoran with his young family, where he is listed as a limeburner.

From your reports it seems Devoran limekiln was not a good place to work as my grandfather died an untimely death too but not at the limekiln. It was John who drowned in the Truro River in 1890.

As as aside, I remember lime being spread on the fields and seeing white ‘dust’ being blown off by the breeze. I also remember my Dad using white wash on the wash house and outside toilet walls.