We should be grateful to those who record the everyday events of their life. Elsie Thomas of Silverwell did just that, and her children, Clarice Lean and Ken Thomas, were delighted to agree to its inclusion in the book, Blackwater and its Neighbours by Clive Benney and Tony Mansell. The material has also been the subject of many presentations to Cornish audiences and now, Tony has adapted it for this Cornish Story article.

Elsie circa 1920

Elsie circa 1920

“I was born on the 12th May 1915 to William John and Emmeline Lillian Pearce (née Trenerry). They had moved to Poltaire, a smallholding in Silverwell, when they married in 1912. The village spans two parishes, St Agnes and Perranzabuloe, and we lived in the latter.”

One online source describes a smallholding as a residential property situated within its own land and of a size being more than a garden, but less than a farm. I have always understood such a property to be about 20 acres or less but it is not something with which I would take issue. Whatever its size, it was where Elsie’s parents kept a few cows, some pigs and poultry and, from her later comments, there was a certain amount of arable use as well.

Elsie said that she couldn’t remember much about her early years but at five-years-old she began attending school albeit it was for half-days in a neighbour’s kitchen. To get there she had to walk across the moors. The four children there were taught by a lady who walked each day from Blackwater.

Silverwell Chapel and Sunday School

Silverwell Chapel and Sunday School

Silverwell Chapel clearly played a big part in her life and when she was six she began attending Sunday school there. She said, “It was held in the chapel as it was before the schoolroom was built. My Grannie and Grandpa lived quite near the chapel so I was able to go to their place for dinner: my father took me to the afternoon service and my mother joined us for the evening service. We received a stamp for attendance and there were prizes at the anniversary which was a special ‘do’.”

After a few years, Elsie attended bible class and became a teacher for the little ones. She recalled her fond memories of the annual tea treats which were held at the end of July. “We hired a band and marched through Silverwell – banners and all. After the parade we returned to the field adjoining the chapel where we were given our tea treat buns. The adults and the members of the brass band had a tea and in the evening the band played a concert and ended the day with the Serpentine march.” Her recollection is that the chapel had to cease using a band because of the cost and instead, the children were treated to a trip instead. “But”, she said, “that didn’t catch on”.

When she was about seven, the four children transferred to a morning only school near Mithian Church – possibly a Church of England school – and at the age of ten she attended Mithian School, about three miles from her home. She said, “I left home at 8.00 am and returned at 5.00 pm. I had to walk across fields, a number of lanes and cross a river; it wouldn’t be allowed these days. In wintertime it was getting dark by the time I arrived home.”

Elsie aged 10

Elsie aged 10

Mithian School 1926 with Elsie second right in the back row

Mithian School 1926 with Elsie second right in the back row

Poltaire had no electric supply and Elsie recalled boiling the kettle on a primus stove to make a cup of tea. The Cornish Range stove, or slab, had to be cleaned before it was lit and Friday was stove cleaning day. “The oven had to be removed to clear the soot which had collected around it and the stove had to be black-leaded and the brass-work cleaned with Brasso; a very dirty job but it looked like new when done.”

The Cornish Range or slab

The Cornish Range or slab

“Monday was washday and after the clothes were scrubbed on a wooden tray they were rinsed twice. First in ordinary water and then in blue water known as Bluen. There were no washing machines and some items had to be put through the mangle before being ironed. The men wore stiff collars and these had to be washed, starched and ironed. Some also wore starched cuffs and used cufflinks.”

“There was no radio, television or electric light and as it got dark we had to use candles and oil lamps. To go outdoors we had to use a hurricane lantern.”

The table Tilley lamp

The table Tilley lamp

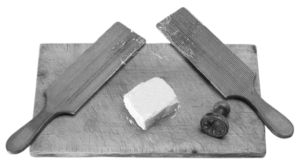

In those days the cows were milked by hand and Elsie described the process of making butter. “The milk was poured into a separator and the cream removed and emptied into a bowl. It was placed on the range and as it warmed, a cream crust formed on the top. The next day this was made into butter by stirring it round and round until the butter milk came out. The butter was washed several times in very cold water and the water removed using pats or beaters. It was then cut and weighed into half and one-pound blocks, stamped with our sign and left to stand on a cold slab. Each time the separator was used it had to be taken to pieces and washed thoroughly, ready for the next milking session.”

Butter pats and stamps

Butter pats and stamps

Something which may seem strange was that young calves, when taken away from their mother, had to be taught to drink from a bucket. Perhaps with painful memories, Elsie described the process of putting her hand in a bucket of milk and pushing the calf’s head down to suck her fingers – and bite!

Teaching a calf to drink

Teaching a calf to drink

The bullocks were walked to market in those days but the pigs were slaughtered at home and taken to the butchers. Eggs were collected once a week by the egg-man with his lightweight wagon on which he also carried a tank of lamp oil.

The pony and trap

The pony and trap

“Mother and I drove our horse and trap to Truro where we sold our butter to the shops, the same shops where we bought our groceries. Our horse, Doxie, was stabled at People’s Palace, off Pydar Street, and an errand boy from H D Brewer brought our groceries to there on a bicycle with a parcel frame on the front. Most things were weighed rather than pre-packed and were then wrapped in brown paper tied up with string. A saddler at Shortlanesend carried out any necessary repairs to Doxie’s harness.”

The errand boy and his bicycle

The errand boy and his bicycle

Sometimes Elsie and her mother visited Truro by horse bus. Together with the many buses from the outlying villages, it was parked at High Cross, by the Cathedral. “If there was a full load”, said Elsie, “some of us had to get off at the bottom of Kenwyn Hill and walk to lighten the load on the horse. There was a seat on top, it was a very nice place to ride in summer. Later, Healey’s of Perranporth ran a motorbus known as a charabanc. Elijah Thomas also ran one from Trevellas and Mithian and Harper and Kellow had a bus service from St Agnes. The Ward family ran a garage at Chiverton Cross and Mr Moyle had a blacksmith shop near there.”

Elsie’s mother did all her own baking apart from the bread which was delivered by the baker. Christmas was a busy time and Elsie recalled stoning the fruit for the mincemeat. She said, “Our suet for the puddings was bought from the butcher and it seems strange now but most of the Christmas post was delivered on Christmas day, by the postman with his pony and jingle.”

Thatched roofs were quite common and these had to be repaired by a thatcher using proper Somerset reed. There was always a risk of it catching fire if there was a chimney fire. Salt was used to try and put it out as water was not very plentiful, other than what was fetched by cart from a river across the field. “Water for the pigs and poultry had to be fetched in this way, often after a day’s harvesting, but the bullocks made their own way to the river.”

Fetching water from the river

Fetching water from the river

Thrashing (sic)

Thrashing (sic)

Harvesting was a busy time for farmers. Elsie recalled that everyone was involved including neighbours who helped each other in those days. “The hay was cut with a reaper and, when fit, was turned using pikes (1). Most farms had a mowhay where ricks of hay and straw were built. If the weather was uncertain, the hay was temporarily stored in pooks (2) and later brought from the fields to the mowhay by horse and wagon. For the corn harvest, the men cut around the edge of the field with scythes and bound it into sheaves. The remainder of the field was then cut using a horse and binder. Tea or croust [or crib] was taken out to the field with herby beer or some such drink. Later on, the threshing machine arrived pulled by a traction engine for which my father had to fetch coal and water. Three men arrived with the machine and joined us for breakfast and supper – they had to arrive early to get up steam. The men who didn’t have a bicycle or pony and shay stayed on the farm overnight. The corn was threshed, the grain stored in the barn and the straw put in bundles in a rick. The ricks had to be thatched and roped down – it was generally my job to carry the rope with a long pole. Hay was cut from the rick with hay-knives as and when needed for cattle feed. The dowst was stored for use in winter.”

The scythe in use

The scythe in use

The horse and binder which cut and bound the material into sheaves

The horse and binder which cut and bound the material into sheaves

Building the rick with a hay-pole

Building the rick with a hay-pole

Ricks in the mowhay

Ricks in the mowhay

“We picked elder flowers, laid them out on newspapers to dry and stored them for winter to make elder tea. A few pieces were placed in a jug and boiling water added. A few drops of peppermint helped as elder has a very faint taste. It was supposed to be a good treatment for colds. I can also remember that salt was sold in hard blocks for 2d [just under 1p].”

Elsie recalled that there was usually someone locally who would mend boots and shoes and someone else who would trim men’s hair but she said, “No perms for women back then!”

At school, there was a Cornish Range which was looked after by the boys and she recalled that they would get the oven really hot and if she took a pasty to be warmed, it was usually burnt. She often gave up. “Our headmaster came from St Agnes and his daughter, who was the infants’ teacher, walked, just like us. The other teacher, Mrs Tippett, cycled from Blackwater. There were no flush toilets, just buckets. On one afternoon a week the girls were taught needlework and the boys, gardening. The year after I left there were cookery lessons so I missed them.”

Will and Lily Pearce with Elsie at Poltaire, Silverwell

Will and Lily Pearce with Elsie at Poltaire, Silverwell

In those days the roadmen maintained a particular length of road: it was also their job to trim the hedges and clean the ditches. Some would arrive with a pony and shay which was usually put in a nearby field.

There were a few Gypsy camps around where the men sharpened knives and scissors and made pegs which the women travelled around selling. “They were Romany,” said Elsie, “not the new-age travellers of today. There were rabbit trappers who would set their traps and tell us to keep our cats in the house but we had some which came home minus a paw – poor things. Farmers fetched their milled stuff, pig and cattle food, by horse and cart from a near-by mill but, in time, this was delivered by lorry. Few people, if any, had telephones and we had to cycle to deliver messages or to get help. Neighbours were always ready to help each other in busy times or if there was sickness.”

Elsie at Poltaire, Silverwell

Elsie at Poltaire, Silverwell

“Later, in 1937 or 1938, my husband Francis, grew broccoli and took them to Truro by horse and cart to sell. On one occasion our horse, Laddie, ran away, cart and all, but someone caught him and no harm was done. We also grew anemones, packed them in boxes and sent them up-country by train – all done to earn a bit extra. My mother died in 1941 and Miss Quick became housekeeper to my father. She was very fastidious and is said to have even polished the milk churns.”

Elsie Thomas (née Pearce) 1915-2004.

Elsie Thomas (née Pearce) 1915-2004.

This may seem like an abrupt ending but the day the notes were passed to me, with the promise of more to come, Elsie died, but it was in the knowledge that her story would be published for others to read. (Tony Mansell)

End notes:

- Pike: a lightweight two-pronged fork.

- Pooks: a group of sheaves set vertically.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history and is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and a sub-editor with Cornish Story: an Institute of Cornish Studies initiative.

What a lovely story. Life may have been tough, but would that life today be at such a gentle pace.

Thank youTony and Clive.

John Wilson. St Agnes.