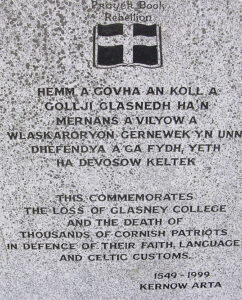

In June 2007, the Rt Revd Bill Ind, Bishop of Truro, wrote: “I am often asked about my attitude to the Prayer Book Rebellion and in my opinion, there is no doubt that the English Government behaved brutally and stupidly and killed many Cornish people. I don’t think apologising for something that happened over 500 years ago helps, but I am sorry about what happened and I think it was an enormous mistake.”

Much has been written about this disastrous episode in Cornish history: a time when our ancestors were prepared to rebel and even shed their blood in defence of their religion.

History is sometimes hard to pin down because memories differ and narratives vary. It’s often a mix of what happened, what may have happened and what the winning side claimed to have happened. Historians research and interpret the events, often putting their own slant on them, so acceptance of the events as totally accurate is often down to the individual. In this case however, we do have the benefit of some contemporary evidence.

In addition to the many books and papers on the subject, it occurred to me that there is a place for a potted history, a concise day-by-day version of events, and what follows is a summary of the views of a number of historians. Inevitably, opinions vary, but only in the detail and I believe this chronological record to be a fair representation of this dreadful period in our Cornish history.

The Beginnings

22nd April 1509: Henry VIII became King of England and Ireland.

30th March 1533: Thomas Cranmer was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury.

1533: Henry VIII broke with Rome and established the Church of England but it was not motivated by theological differences and he remained a Catholic to his dying day.

1534: Henry VIII appointed himself Supreme Head of the Church of England.

22nd June 1535: Bishop John Fisher refused to acknowledge Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the Church of England and was found guilty of treason and executed.

6th July 1535: Sir Thomas More refused to acknowledge Henry VIII as the Supreme Head of the Church of England and was found guilty of treason and executed.

1536-1541: The ‘Dissolution of the Monasteries,’ the dismantling and suppression of Catholic monasteries, abbeys, and priories in England and Wales.

October 1536: The ‘Pilgrimage of Grace,’ a major uprising in Northern England in response to the religious reforms, particularly the break with Rome and the dissolution of monasteries.

1537: St Keverne Fishermen, Carpyssacke and Treglosacke, supported the northern rebels and were possibly imprisoned and executed.

June 1539: Henry VIII’s ‘Act of the Six Articles’ (1) reasserted Catholic Doctrine, affirmed certain Catholic doctrines and imposed penalties for their denial. It was a response to the growing influence of Protestantism and its denial was punishable in law.

1547

28th January: Henry VIII died but he had directed that his Six Articles of Religion were to remain in place until his son came of age.

The Real Reformation

28th January: Edward VI became King of England and Ireland.

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, appointed Lord Protector of England during the minority of King Edward VI.

September: The King and his advisers, particularly Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, began a religious revolution.

Thomas Cranmer’s first edition of ‘The Book of Homilies’ (2) published.

The Act of Uniformity (3) proposed to establish Protestantism as the country’s official religion.

- The Book of Common Prayer was to be used in all churches.

- Henry’s Six Articles of Religion were to be repealed which meant the denial of Transubstantiation, the acceptance that priests could marry and the banning of Catholic Mass.

- Statues, images and Catholic regalia were to be removed from churches.

- The celebration of saints’ days and feasts were banned.

- Membership of guilds, where folk prayed for deceased family members, was to be discontinued.

- Reciting the Rosary and the granting of Indulgences was to be discontinued.

The proposed changes were huge and people were troubled and angry.

1548

6th February: Proclamation made ordering the removal of images from churches.

Inventories of all church possessions to be made: bells, vestments, ornaments, plate etc.

The Helston Revolt

April: William Body, a seemingly arrogant and unpopular man, had bought the archdeaconry of Cornwall and it was his role to organize the removal of church items.

Corrupt doctrines and superstitious practices to be abolished including the destruction of “the roots of the weeds, the popish doctrine of transubstantiation, of the real presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Sacrament of the Altar.”

Body had previously encountered problems at St Stephen’s Church, Launceston, where a scuffle had broken out and the doors had been locked against him.

He met a similar reaction at Penryn and the protests and demonstrations led him to ask the Privy Council what he should do. He was instructed to continue.

5th April: William Body arrived in Helston and began removing religious images and statues from the parish church.

He was in the church as about 1,000 protestors gathered outside with swords, staffs and bows.

Father Martin Geoffrey, the St Keverne Priest, declared, “There will be no further sacrilege.”

Body was threatened and escaped to a house in Church Street from where he was dragged out and stabbed to death by William Kilter and Pascoe Trevanian.

6th April: In Helston Market Square, John Rasseigh of Helston declared, “There will be the law made by King Henry VIII and nothing else until the king reaches the age of twenty-four. Those whoso would defend Body, or follow such new fashions as he did, we will punish him likewise.”

7th April: An attempt to arrest John Rasseigh was prevented by about 3,000 people who had gathered to protect him. “We will be against the officers if there was just one of them taken to trial at the sessions in Helston the next week.”

There was talk of rebellion: “On Tuesday next at the general sessions to be holden in Helston we will be there with a greater number to see if any man will be revenged herein.”

Sir William Godolphin and fellow justices of the peace appealed for assistance.

8th April: The Privy Council suggested that it was, “Just a localized insurrection … send in the army.”

8th May: Announced that a new Order of Service was to be introduced by Easter 1549 – in English!

The Privy Council ordered an army to be formed.

17th May: At Launceston – Henry Blase and Sir Richard Edgecumbe entered Cornwall and formed a posse from east Cornwall: (St Winnow, Morval, Lanteglos, Boconnoc, Launceston and Stratton).

A proclamation offering a pardon to the rioters was issued – it had 28 exceptions.

28th May: The Trial of the ‘28 exceptions’ was held at Launceston under Richard Grenville. The charges were High treason, Felony and Murder.

William Kilter and Pascoe Trevanian pleaded guilty to stabbing William Body – they were hung, drawn and quartered at Launceston.

The other 26 were dealt with in various ways. (4)

People’s Catholic devotions were deep and the Mass continued: women still carried rosaries and recited to companions in church.

Archbishop Cranmer referred to the “Desire of lewd lay people to see the Host at least once a day,” and Protestant preacher Dr Tongue, was sent, “To preach to poor Cornishmen.”

Protests and disturbances continued throughout the kingdom and Cranmer declared, “… the Priests are inciting people,” and that it was, “Disobedience and stubbornness against his Majesty’s godly proceedings.”

Church services became subject to a special licence and the use of the 1547 Book of Homilies was enforced in law.

Catholic valuables and images continued to be stripped from churches including from the Priory Church at Bodmin but St Petroc’s bones had been hidden.

1549

21st January: Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity (5) heralding the introduction of Protestant doctrine and practice and establishing the Book of Common Prayer as the sole legal form of worship in England and Wales. It was to be in use by Whit Sunday, the 9th June.

Considerable unrest across what was a Catholic country.

Cornwall

6th June: Cornish protestors gathered at Castle Canyke, Bodmin, and two gentlemen were placed in charge: 36-year-old Humphry Arundell of Helland and John Wynslade of Tregarrick.

The revolt grew and other leading names joined: Robert Smith or Smyth of St Germans (yeoman), Thomas Holmes of Blisland (yeoman and servant of Sir John Arundell), William Harris, James and Henry Rosogan and Catholic Priests: Roger Barrett, John Thompson, Richard Bennett of St Veep & St Neot and Simon Morton of Poundstock.

Circa 8th June: The protestors sent an initial set of demands to the authorities in London: it included that Henry VIII’s ‘Six Articles’ should remain in place until the present king reached the age of twenty-four.

The Privy Council’s eventual reply was both conciliatory and threatening.

9th June (Whit Sunday): The new Book of Common Prayer was first used. The Latin liturgical rites were declared unlawful and magistrates were ordered to enforce the changes. All Services were to be in English with punishment for persistent refusal (clerics were to be given life imprisonment and laymen were to lose all possessions).

Fearing an attack by those remaining at The Mount, the Cornish rebels sent a small force to suppress any danger: the prisoners were placed in Lanson jail.

The King eventually rejected the Cornish demands but offered a pardon to those who laid down their arms.

The Cornish protest group numbered about 3,000 and was still growing. The decision was made to deliver the grievances to London.

Arundell led his party away to the east. At some place it split into two with one group heading for Polson Bridge and the other, for Plymouth. In due course they would merge again – at Crediton.

On the way to Plymouth, Robert Smyth captured Trematon Castle and Richard Grenville was taken as a prisoner to Launceston Jail.

Plymouth Town surrendered without a fight and Smyth headed for Crediton.

Devon

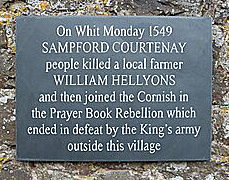

The beginning of the Devon revolt was in Sampford Courtenay, a small village about six miles north-east of Okehampton.

Early June: As in Cornwall, there was considerable unrest and opposition to the religious changes.

9th June (Whit Sunday): Seventy-year-old Father Wm Harper, vicar of St Andrew’s Church, led the service with no Catholic attire and using the new Book of Common Prayer.

After the service the talk was of the Cornish rebels and of the vicar’s capitulation to authority.

10th June: Thomas Underhill, a tailor, and William Segar, a labourer, challenged Father Harper and asked if he intended to use the new service that day.

He replied, “In obedience of the law I must use the new service book.”

Thomas Underhill responded, “That indeed you will not! We will stand by the laws and ordinances touching Christian religion as were appointed by King Henry until King Edward reaches the age of twenty-four years, for so his father appointed it.”

Father Harper donned his ‘Popish attire’ and said the Catholic Mass.

After the service there were speeches against the religious changes and further news of the approaching Cornishmen.

Four Justices of the Peace and their escort arrived, but the protesters were not about to give way and they left again not having made any progress.

But then, William Hellyons, stood and renounced the rebellion. He was shouted down and hacked to death.

Humphry Arundell and his party (perhaps three thousand including the famous Cornish archers) arrived at his estate near Crediton and the Sampford Courtney men joined them.

15th June: Miles Coverdale was sent to reconcile the people to the religious changes.

The Privy Council: “Should the rebels come peaceably to justice, let six be hanged of the ripest of them without redemption, the rest to remain in prison.”

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, urged restraint and Sir Peter Carew and his uncle, Sir Gawen Carew, were sent to appease the rebels.

21st June: The Carews arrived and with them they had the offer of pardon.

21st June: A joint Cornwall/Devon force occupied Crediton and the Carews and a small party rode the seven miles to meet them.

The rebels had erected barricades across the road between two barns and the area was defended by men with bows and arrows and other weapons.

The Carews approached on foot and asked to parley, but the offer was rejected.

The Carews attacked but it was soon clear that they were outnumbered and some of their party were killed: they were forced to retreat.

Either with or without the Carews’ knowledge, one of the attackers set fire to the barns.

We do not know if the rebels suffered any casualties but most escaped and fled the area.

With no one to parley with and no one to receive the offer of pardon, the Carews returned to Exeter to report that the rising was more serious than thought. Exeter could be in danger.

The firing of the barns seemed to act as a catalyst and support for the rebels quickly grew. They began to blockade the roads and fortify villages.

Tension was rising and there were threats made against any local gentry who supported the new form of religion.

Walter Raleigh (snr) approached an old lady in Clyst St Mary carrying her beads and prayer book. He told her that she was breaking the law and threatened her. She ran into the church and the congregation chased after Raleigh. He managed to escape but such was the strength of feeling at this time.

Some of the rebels moved into Clyst St Mary and fortified it.

22nd June: At a conference at the Mermaid Inn, in Exeter, the Carews were criticised for their failure at Crediton. They claimed they needed more men and pointed to Walter Raleigh’s narrow escape and the fact that the rebels had fortified Clyst St Mary. It was decided that the Carews would head an expedition to that village and this time the group would include Sir Thomas Denys and Sir Hugh Pollard.

23rd June: The party left The Mermaid and headed for the bridge over the River Clyst. It was blockaded and Sir Peter Carew approached it on foot and asked to parley but no one trusted the Carews. They would not allow him to cross but would talk to Denys, Pollard and Thomas Yarde – without an escort.

The meeting lasted all day and into the evening, and while it was still going on, Carew’s men were spotted seemingly making arrangements for an attack. This heightened the tension and the negotiations broke up having made no progress.

At the subsequent meeting in The Mermaid, the Carews blamed Pollard and Denys for their lack of success and Pollard and Denys blamed the Carews.

24th June: A siege of Exeter seemed inevitable.

Sir John Russell (Steward of the Duchy of Cornwall, Warden of the Stannaries and President of the Council of the West) was sent to Devon with Dr Gregory and Dr Reynolds who were to preach the people to obedience.

Russell’s orders were to use restraint, discover the causes and use persuasion. If that failed, he was to raise a local force to confront the rebels.

24th June: Russell at Hinton St George, Somerset.

24th June: Sir Gawen Carew and others left Exeter: many were captured and imprisoned by the rebels, including Walter Raleigh. He, and others, were imprisoned in St Sidwell’s Church.

Others left the city and joined Arundell.

24th June: Sir Peter Carew headed for London, to report on what had happened and with a request from Russell for more men.

Sir Peter Carew was given a hard time in London and accused of exceeding his warrant by burning the barns. Baron Rich even suggested that he could be hanged but he managed to convince them that he had followed orders. He also persuaded them to send troops and let him finish the job.

25th June: Russell at Honiton awaiting reinforcements.

The rebels sent a new set of Articles (6) (demands of the Western Rebels) to the Privy Council in London.

Archbishop Cranmer’s response: “A complete, pathetic manifesto of Catholic reaction.”

Edward VI’s response: “We let you know that as you see our mercies abundantlie, so if you provoke us further we sweare to you by the living God ye shall feel the power of the same God in our swords.”

Edward Seymour’s (Lord Protector) response: “Nothing to worry about, it will die a natural death.”

Cornishman Nicholas Udall’s response: “… my simple and plain speaking countrymen (for I speak to the ignorant that have been deceived, and not to the malicious) …” He suggested that they had been led astray and said that the Prayer Book could be translated into Cornish.

29th June: In London, an army was being assembled for war against Scotland but it seems that the seriousness of the rebellion was finally recognized and a force was to be diverted to the west.

Humphry Arundell approached Exeter and threatened to besiege it if they refused to surrender.

Despite the mayor, John Blackaller, and the majority of citizens, being Catholic, they refused to join the rebels.

The five great gates of the City were closed against the rebels.

2nd July: Lord John Russell at Honiton: “I dare not attack until Italian and German troops arrive.”

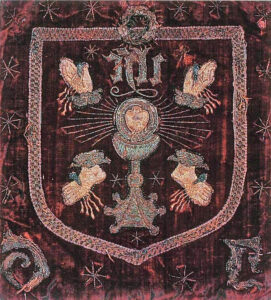

The Rebels crossed the river by the Church of St Thomas and approached Exeter’s West Gate with their banner of the ‘five wounds’ (7) flying,

2nd July: According to John Hooker (8) the siege began with about 2,000 men thinly spread.

The rebels did not have any siege artillery but they placed snipers, attempted to scale the walls, blockaded approach roads and cut off food supplies.

Later commentators have suggested that a more successful action may have been to blockade the city and march for London but whether this was considered, we do not know.

The Rebels’ numbers increased daily and is said to have reached 5,000 or more.

Cornish miners began to dig a tunnel under West Gate in an attempt to undermine the city wall. They placed gunpowder below the wall and planned to explode it. A visiting miner within the city however, had discovered their efforts and had used a flat pan of water to detect vibrations caused by their digging. A hole was dug above them and their efforts were extinguished by filling it with water.

Another plan was to send fire-balls into the city but Father Robert Welsh (a Penryn man and Priest of St Thomas’ Exe Island) persuaded the rebels to spare the city.

An attempt was made at burning the West Gate and the South Gate but the defenders suddenly opened the gates and blasted the attackers with their heavy guns filled with stones and metal.

There were fears of treachery within the city and even the Mayor was sympathetic to the rebels’ cause but loyalty to the King was paramount and the rebels never succeeded in entering the city.

9th July: Exeter had food for only a few days – it was feared that the city could fall any hour.

9th July: Russell, at Honiton, had not been successful in raising a local force and he now feared a rebel attack.

Russell withdrew to Dorset to await reinforcements, but Peter Carew successfully persuaded him to return to Honiton.

10th July: Edward Seymour sent 150 Italian arquebusiers to Russell.

12th July: Sir John Russell was told of this and that more reinforcements were on their way.

18th July: News of the Exeter siege reached London and there were fears of a rebel attack there: Martial Law was declared and orders given to destroy the bridge at Staines if the rebels approached. There were fears that gates could be opened by rebel sympathisers and rumours that Princess Mary had sanctioned the rising. She was asked to forgo the licence to celebrate Mass in her home.

Lord Grey delayed.

Russell found it difficult to persuade men to enlist and Seymour told him to hang a few as an example.

The Carews managed to raise some troops from Dorset.

21st July: The 150 Italian arquebusiers under Genoese nobleman, Paolo Batista Spinola, arrived.

22nd July: Edward Seymour losing patience – conversations with John Russell were less than cordial.

Russell obtained funds to employ local men.

24th July: The Privy Council’s second reply to the demands: “To the four captains and four governors of the camps.” It was little different from the first.

Late July: The Privy Council’s third reply was addressed: “To the simple and plain-speaking Cornishman who has been aroused by the sinister persuasion of certain seditious papists, whelps of the Roman litter, abusing your simplicity and lightness of credit.” It was sympathetic, pleading and certainly threatening.

Russell, still awaiting Lord Grey, left Honiton and headed for Exeter but found that the rebels had blocked the roads. He made a detour to Ottery St Mary where his army spent the night. On leaving, he set fire to the village and returned to Honiton.

Lord Grey and Sir William Herbert were a few days away.

Relations between Russell and Seymour were increasingly fraught.

Russell’s army was growing and Arundell decided to attack before more reinforcements arrived.

27th July: Arundell blockaded Exeter and marched towards Honiton.

Arundell was at Fenny Bridges on the River Otter when Russell marched to confront him.

The rebels held the bridges and Russell attempted to lure them onto open ground.

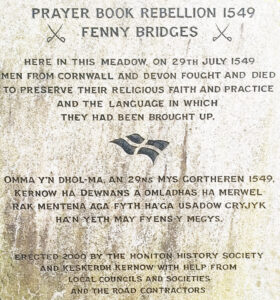

28th July: The Carews led an assault on the bridge and eventually managed to cross. The armies then clashed in a nearby meadow and both sides suffered heavy casualties. Many rebels were killed and others were chased from the field but while Russell’s mercenaries were busy gathering spoils, a group of Cornish archers attacked and killed many. This surprise attack enabled the outnumbered rebels to escape into the surrounding countryside and head for Exeter. Russell’s superior equipment and experience had won the day and the site of the battle was later dubbed ‘Bloody Meadow’. John Hooker wrote: “The fight for the time was very sharp and cruel, for the Cornishmen were very lusty and fresh and fully bent to fight out the matter.”

Russell gave chase for about three miles but then returned to Honiton, perhaps because he thought the ringing church bells indicated an attack there.

Late July: The situation in Exeter was critical and many wished to surrender. The citizens had resorted to eating horse bread (bread made for animals) but even that was in short supply.

Lord Wm Grey’s army arrived.

Conditions in Exeter was desperate and plans were being made to fight their way out when they heard the news from Fenny Bridges.

31st July: An attempted Catholic rising within Exeter was accompanied by the call, “Come out you heretics. Ye two-penny book men! Where be ye? By God’s wounds, by God’s blood! We will not be penned in to serve your turn. We will go out and have in our neighbours. They be honest and Godly men.” The Mayor, John Blackaller, managed to thwart the attempted uprising.

3rd August: Russell headed for Exeter with perhaps a thousand well-armed and well-trained troops.

He camped on the Heath above Clyst St Mary.

The rebels attacked but were beaten back with casualties on both sides.

The rebels moved into the village and blockaded it.

4th August: Sir William Francis attacked but lost many men to the Cornish archers.

Sir Thomas Pomeroy, a rebel commander, then sounded the attack but it was a ploy which caused panic amongst Russell’s troops who turned and abandoned their armaments to the grateful rebels.

The attackers advanced but were ambushed and Sir William Francis was killed.

Russell attacked again. The rebels sheltered in the houses but the thatched roofs were fired and as they ran out, many were cut down. Hooker wrote: “Cruel and bloody was that day for some were slain with the sword, some burned in the houses, some shifted for themselves, were taken prisoner, and many thinking to escape over the water were drowned so that there were dead that day by one and other about a thousand men.”

Russell headed for the bridge over the Clyst but it had been blockaded and was defended by a rebel with a single piece of artillery.

After a few casualties, a group of Russell’s men headed upstream, crossed the river and shot the rebel gunner in the back.

Many of the rebels had escaped and Russell spent the night nearby – on Clyst Heath. From there they could see Aylesbeare Common.

During the evening, someone spotted sun glinting on what seemed like armour – possibly another rebel attack! In what was the greatest atrocity of the war, Russell and/or Lord Grey ordered his men to cut the throats of their 900 plus prisoners.

5th August: During the early morning, the rebels, intent on revenge for the savage slaughter, drew in men from the Exeter blockade and attacked Russell’s camp with arrows, shot and captured artillery, inflicting many losses. Russell’s army was quickly back in action and the rebels found themselves attacked from all sides. Some managed to escape back to Exeter but others, with no line of retreat, refused to surrender and suffered a heavy defeat.

John Hooker: “Valiantly and stoutly they stood to their tackle, and would not give over as long as life or limb lasted, yet in the end they were all overthrown and few or none left alive.”

John Hooker: “Great was the slaughter and cruel was the fight and such was the valour and stoutness of these men [the rebels] that the Lord Grey reported that he had never seen the like, nor taken part in such a murderous fray.”

Russell de-camped and headed for Topsham.

With Russell’s army on its way, and news that Sir William Herbert and his Welsh army would soon be there, the rebels withdrew from Exeter and marched away under cover of darkness, the Cornish to the west and the Devon men to their homes and to the east.

Exeter’s starving citizens poured out to try and find food.

6th August: Russell arrived at Exeter but because of the extreme shortage of food, his army was denied entry and camped for about three days in St John’s Fields next to Southernhay.

Herbert arrived and Hooker wrote that the Welshmen came too late for the fray yet soon enough to play.

9th August: Russell entered the city to great acclaim and the Mayor and gentlemen of Exeter were thanked for “faithfully keeping of the city.” Exeter celebrated its survival.

A special levy was placed on papists sympathizers who had refused to defend the city.

The Privy Council appointed a small committee to assist Russell: Grey, Herbert, The Paulets, Sir Andrew Dudley and Sir Thomas Speke. The Carews were not included.

Sir John Russell re-distributed the rebels’ estates and punished the leaders but John Hooker wrote: “Russell was merciful to common people … did daily pardon infinite numbers.”

10th August: In London there was a service of thanksgiving and Cranmer preached on the sin of rebellion.

Russell was ordered to disband much of his army to reduce cost.

11th August: Edward Seymour instructed Russell to: “Execute the heads and stirrers of the rebellion … in so diverse places as you may to the more terror of the unruly. To prevent such kind of rebellion again.”

The Reverend Robert Welsh, who had prevented Exeter being fire-bombed, was hauled in chains to the top of St Thomas church tower with, according to John Hooker, “Holy-water bucket, a sprinkle, a sacring bell, a pair of beads and such other like popish trash hanged around him.” He “Takes his death with quiet courage.”

But it was not over – Arundell was re-forming.

16th August: Russell, William Herbert and Lord Grey set out to confront him.

Arundell, with over 1,000 men, was at Sampford Courtney which he had blockaded.

Saturday 17th August: Grey and Herbert swept aside the outer blockade and headed into the village. Russell was some way behind.

Arundell, within the village, launched a fierce counterattack but Grey’s superior force swung the battle. The rebels withdrew but John Hooker wrote: “Though the rebels were nothing nor in order nor in company nor in experience to be compared to the others, yet were at a point they would not yield to no persuasions, nor did, but most manfully did abide a fight and never gave over until that both in the town and in the field they were all for the most part taken or slain.” Underhill, the Sampford Courtney tailor was one of the casualties here.

19th August: Humphry Arundell, William Winslade and a few others made for Okehampton and from there they headed for Launceston.

Russell reported: “My army has killed between five and six hundred enemy and our pursuit of the Cornish retreat killed a further seven hundred … of our part there were many hurt, but not passing ten or twelve slain … the Lord Grey and Mr Herbert have served notably. Every gentleman and captain did their part so well as I know not whom first to commend. I have given orders to all ports that none of the rebels shall pass that way.”

Edward Seymour to Russell: “Pursue the rebels before they can re-build.”

Russell ordered into Cornwall: “He shall not suffer those rebels to breathe.”

Russell reported that he had sent the Carews Launceston, “… to hold the town in stay.”

Russell had asked for 1,000 men to land to the rear of the rebels in Cornwall but only 200 or 300 men from naval vessels were available.

John Hooker: “Now, after the last battle, minding to make sure of all things, the Lord Russell marcheth into Cornwall and following his former course causeth execution to be done upon a great many and especially on the bell-wethers and ringleaders.”

Arundell, William Wynslade, Maunder and Bowyer, Bodmin’s Mayor, captured in Launceston. John Wynslade captured at Bodmin. They were taken to Rougemont Castle in Exeter.

Sir William Herbert moved up the Exe Valley in pursuit of a thousand or so Deven rebels – many were captured or executed.

Russell appointed Sir Anthony Kingston, to continue his work – to execute Cornish rebels with sufficient severity to inspire terror in people’s hearts. Kingston seems to have undertaken his work of hunting down papists, burning mass-books, ensuring new service used and seeking pacification (vengeance) with sadistic pleasure.

At Bodmin, Kingston and Nicholas Boyer, the new mayor, inspected the gibbet.

Sir Anthony Kingston: “Think you they be strong enough?”

“Yes Sir, that they are,” was Boyer’s response.

Kingston: “Well then, get you even up to them for they are provided for you.”

Boyer protested, “I trust you mean no such thing to me.”

“Sir, there is no remedy; you have been a busy rebel and therefore this is appointed for your reward”

It is suggested that John Payne, the Port Reeve or Mayor of St Ives, had the same trick played on him.

The Privy Council ordered Russell to send up the chief captains: Arundell, Pomeroy, Maunder, the mayor of Bodmin, Wise and Harris. Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, wanted Sir Thomas Pomeroy pardoned but it had to be, “Done quietly and on condition he betrays others and renounces popish errors.”

8th September: Humphrey Arundell, John Wynslade, John Bury and Thomas Holmes, Thomas Pomeroy, William Wynslade, William Fortescue, John Wise or Wyse, and Harris left Exeter for London where they were imprisoned in Fleet. With them was John Kestell, Arundell’s secretary, who been spying for Russell throughout.

12th September: The Privy Council ordered the removal of church bells but in many cases only the clappers were taken down.

Before 22nd October: Arundell, John Wynslade, John Bury and Thomas Holmes transferred to the Tower.

1st November: Pomeroy, William Wynslade, Fortescue, Wise and Harris discharged from Fleet Prison.

Tuesday 26th November: Arundell, Wynslade, Bury and Holmes were taken by boat to Westminster Hall for trial. Found guilty of high treason, they returned to the Tower of London to await execution. Some of the evidence against Arundell was provided by the traitor, John Kestle, who Russell had said, “… had defected amidst the hottest stirs with information.”

Whilst in the Tower, they were joined by Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who had been arrested and was to be executed for treason.

1550

27th January: Humphrey Arundell, John Wynslade, John Bury and Thomas Holmes were dragged on a hurdle to Tyburn Tree where they were hung, drawn and quartered and their limbs exhibited in various parts of the city and their heads put on pikestaffs (gibbeted) on London Bridge.

Rebel Losses

The rebel losses have been the subject of much discussion, and disagreement:

It is likely that there were some losses at the Crediton confrontation and in the siege before Exeter but we do not have any numbers.

The plaque at Fenny Bridges suggests that 1,549 were lost there.

John Hooker states that 1,000 were killed in the battle at Clyst St Mary

Over 900 were said to have been murdered at Clyst St Mary.

Russell claims 600 rebel dead at Sampford Courtenay and a further 700 in the outlying areas

John Hooker suggested that about 4,000 rebels were killed in Devon but if the above figure are correct, it appears to be nearer 5,000.

Added to that are the subsequent executions … suggested to be 1,000 in Devon and about the same in Cornwall (although the latter does seem high).

The estimated population of Cornwall in 1549 was about 76,000 and if the Cornish losses are in the region of 4,000, it equates to about 5% of the population and a much higher percentage of the active males.

Quite apart from the casualties, the legislation resulted in the imposition of an unpopular religion and a massive blow to the Cornish Language.

End Notes:

- The Act of the Six Articles June 1539 focused on six key issues:

Transubstantiation: The first article declared that the bread and wine in communion become the body and blood of Christ. Denial of this belief was punishable by death.

Communion in Both kinds: The second article stated that communion in both bread and wine (as practiced by Protestants) was unnecessary.

Clerical Celibacy: The third article mandated that priests should not marry.

Vows of Chastity: The fourth article stated that vows of chastity or widowhood should be observed.

Private Masses: The fifth article upheld the practice of private masses.

Auricular Confession: The sixth article required that auricular confession to priests be continued. (Auricular confession is a sacrament involving the confessing of one’s grave sins to a qualified priest for absolution.)

Penalties for denying the first article (transubstantiation) included forfeiture of property and death by burning. Denial of the other five articles could lead to confiscation of property and execution as a felon.

- The Books of Homilies contained sermons developing the authorized reformed doctrines of the Church of England.

- The (First) Act of Uniformity 1547 was a significant piece of legislation aimed to standardise religious worship and practices throughout the kingdom. It established the Book of Common Prayer which provided the prayers and the order of services to be used in all churches.

- The website Cornwall For Ever (https://www.cornwallforever.co.uk/history/the-killing-of-william-body) lists the 28 people:

Martin Geoffrey, priest of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in London on 7th June.

John Kilter, farmer of Constantine: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

William Kilter, landowner of Constantine: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

Pascoe Trevanian, mariner of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

Henry Tyrlever, mariner of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

John Trybo, farmer of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

Thomas Tyrlan Vian, mariner of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

Richard Rawe, farmer of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

Martin Ressiegh, farmer of St Keverne: hanged, drawn and quartered in Launceston.

James Robert: mariner of St Keverne: hanged.

Michael John, mariner of St Keverne: arrested but released.

John Tregena, mariner of St Keverne: arrested but released.

James Tregena, mariner of St Keverne: arrested but released.

Maurice Tryball, mariner of St Keverne: arrested but released.

John Chykose, farmer of Gwennap: arrested but released.

Alan Rawe, farmer of Gwennap: arrested but released.

Laurence Breton, groom of Gwennap: arrested but released.

Michael Vian Breton, farmer of Gwennap: arrested but released.

Richard Trewela, landowner of Redruth: arrested but released.

John Williams, miller of Ruan Minor: arrested but released.

Hugh Mason of Grade: arrested but released.

William Amys, farmer of Grade: pardoned.

John Piers, mariner of St Keverne: pardoned.

Edmund Irish, blacksmith of St Keverne: pardoned.

John William Trybo: pardoned.

John Kelyan, landowner of Illogan: pardoned.

William Thomas, mariner of Mullion: pardoned.

Oliver Ryse, farmer of Perranzabuloe: pardoned.

One man was taken to Plymouth and hanged on Plymouth Hoe, a supposed warning to the people of Devon not to resist the religious changes.

- The Act of Uniformity 1551 / 1552 was one of the last steps taken by Edward VI and his councillors to make England a more Protestant country. It replaced the 1549 Book of Common prayer with a more clearly Protestant version. Anyone who attended or administered a service where this liturgy was not used faced six months imprisonment for a first offence, one year for a second offence, and life for a third.

- Articles of us commoners of Devon and Cornwall in divers camps east and west of Exeter

Petition against the introduction of the New Order of Mass in England.

We will have the General Council and Holy Decrees of our forefathers observed, kept, and performed, and whosoever will gainsay them, we hold them as heretics.

Restoration of Statute of Six Articles of Henry VIII against heresy.

We will have the Mass in Latin as was before, and celebrated by the Priest without man or woman communicating with him.

We will have the Sacrament hang over the High Altar and there be worshipped as it was wont to be, and they, which will not thereto consent, we will have them die like heretics against the Holy Catholic Faith.

We will have the Sacrament of the Altar, but only at Easter delivered to the lay people and then only in one kind.

We will have that our Curates shall minister the Sacrament of Baptism at all times as well in the week day as on the Holy Day.

We will have only bread and Holy Water made every Sunday, Palms and Ashes at times accustomed. Images to be set up in every church, and all other ancient ceremonies.

We will not receive the New Service because it is but like a Christmas game, but we will have our old service of Matins, Mass, Evensong [Vespers], and Procession in Latin as it was before. And so we the Cornish men (whereof certain of us understand no English) utterly refuse this new English.

We will have every preacher in his sermon and every Priest at his Mass, pray especially by name for the Souls in purgatory as our forefathers did.

(Calling in of the English translation of the Scriptures, i.e., unauthorized translations.)

(Demanding the release of Dr. Moreman and Dr. Crispin, two Canons of Exeter, who were imprisoned in the Tower.)

(Demanding the recall of Cardinal Pole and his promotion to be of the King’s Council.)

(Demanding the restriction of the number of servants a man might have.)

(Restoration of half the abbey and chantry lands and endowments, and foundation of two abbeys in every county.)

For the particular griefs of our Country, we will have them so ordered as Humphrey Arundell and Henry Bray, the King’s Mayor of Bodmin, shall inform the King’s Majesty, if they may have safe conduct under the King’s Great Seal to pass and repass with a Herald of Arms.

By us: Humphrey Arundel, John Berry, Thomas Underhill, John Sloeman, William Segar, the chief captains and by John Thompson, priest; Henry Bray, mayor of Bodwin; Henry Lee, mayor of Torrington and Roger Barret, priest; as the four governors of the camps.

- The ‘Banner of the Five Wounds of Christ,’ also known as the ‘Banner of the Holy Wounds’ or ‘Arms of Christ,’ was a prominent symbol against the reforms of the Catholic Church. The banner depicted the five wounds Christ received during his crucifixion, serving as a reminder of the rebels’ Catholic beliefs and their opposition to the dissolution of monasteries and the break with Rome.

- John Hooker (or “Hoker”) alias John Vowell (c. 1527–1601) of Exeter, was an historian, writer, solicitor, antiquary and civic administrator. He wrote an eye-witness account of the siege of Exeter during the Prayer Book Rebellion.

Resources:

Revolt in the West by John Sturt ISBN 0 86114-776-6

Survey of Cornwall 1602 by Richard Carew ISBN 0-85025-389-6

The Western Rising 1549 by Philip Carman ISBN 1 898386 03 X

The Western Rebellion of 1549: an account of the Insurrections in Devonshire and Cornwall against religious innovations in the reign of Edward VI by Frances Rose-Troup

Tudor Cornwall by A L Rowse ISBN 1 85022 301 7

West Britons by Mark Stoyle ISBN 0 85989 687 0

Tony Mansell is a Cornish historian with a diverse interest in Cornwall’s past and present. He is a Cornish Bard (Skrifer Istori), a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and Co-editor of Cornish Story.