My career with British Rail began in 1951, at the tender age of 15; in those days it was all steam, none of your diesel trade!

It all began with an interview with the school Careers Officer when I expressed an interest in becoming a carpenter. Either he wasn’t listening or he had other ideas because his response was, “Did you know that British Rail are recruiting?” It sounded interesting and he explained that from a starting point of being an engine cleaner, there were promotion opportunities to fireman and driver, all based on examinations and seniority.

British Rail once had a residence requirement that employees had to live within one mile of the engine shed but that had recently been relaxed so the fact that I lived in St Agnes, was not a problem.

My interview and medical was at St Blazey and one of the requirements was that I was not colour-blind. To prove this I had to match six pieces of wool with a similar batch. It all went well and with all the other hurdles cleared, I began my first job, as an engine cleaner at Truro Engine Shed.

I spent my first 18 months there when I heard that there was a shortage of locomotive staff in London due to the war. I applied and soon found myself on the way to Old Oak Common Locomotive Depot. There were about 70 other Great Western Railway staff recruits, all billeted in a hostel and each allocated a room – a very small room!

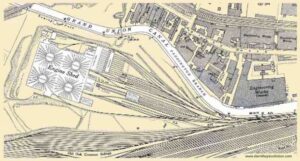

Old Oak Common Locomotive Depot

Old Oak Common Locomotive Depot

It was a long way from home for this young Cornish boy and a rude awakening from my experience of Truro – the depot was huge.

My first day involved a tour of the works and a meeting with a group of drivers. One of them asked me where I was from and when I replied that I was from Truro he said, “Right, you’ll do for me.” He was Reggie Tonkin, originally from Penzance, and I became his fireman.

Old Oak Common Engine Sheds – somewhat larger than Truro!

Old Oak Common Engine Sheds – somewhat larger than Truro!

At 18 years old I was called up for National Service and I chose the Royal Engineers. It seemed like a good fit with steam engines, or so I thought. They obviously had other ideas and I ended up in the Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry (DCLI) at Bodmin. Following training, I was transferred to the Durham Light Infantry in Egypt where I spent 12 months before the regiment returned to Durham where I served my final nine months. In July 1956 I found myself back in Truro. That year was notable for me as it was when I met Hilary, my future wife.

At Truro, I was allocated to a driver called Roy Osborne who was also a Railway Tutor. I received a great deal of help and guidance from him – working in the shunting yard, on local goods trains and then on local passenger trains.

Working under Roy I progressed well, so much so that he recommended that I attend a two-day examination in Swindon to become a junior driver. We were told that at 23 years old I was too young to take the exam but Roy argued my case and ‘the powers that be’ allowed me to attend. When I returned and told Roy that I had passed, he was as pleased as me. I was now a ‘Passed Fireman’ which meant that I was a junior driver and could begin to build my experience to become a fully-fledged driver.

Another fireman I knew travelled to Swindon for the same examination but I’m not sure whether or not he passed. One of his questions related to safety procedures. A part of the fireman’s duties was to look after the canister of flags and detonators: it was his job to issue warnings ahead of the train whilst the guard was responsible for anything to the rear (Safety Rule 55). He was asked what he would do if he discovered a tree across the line. His answer was that he would walk a quarter of a mile ahead and place a detonator on the line, he’d then walk a further quarter of a mile and place two detonators and then walk a further quarter of a mile and place three detonators. “Correct,” was the response, “but what if there was another tree further up the line.” He replied that he would repeat the procedure. “Right,” said the examiner, “but it was a really stormy night so what if there was another tree further on.” The applicant said that he would repeat the same procedure. “Okay, said the examiner but where are you getting all these detonators?” The reply he received was quick but probably unexpected, “The same place you’re getting all these bloody trees!”

A typical footplate

A typical footplate

Most drivers guarded their territory jealously but some, like Ronnie Martin, were different, and would say, ‘I’ll shovel, you drive’. By this I learnt the driver’s job quicker.

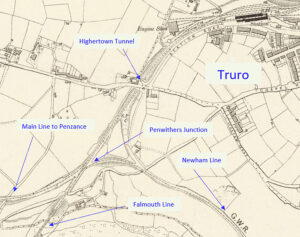

I mainly worked on the Truro to Plymouth main line, the Truro to Falmouth branch, the Newham line and the Chacewater to Newquay branch.

As in most jobs, there were some real characters and many amusing situations. One chap, I’ll call him Ron, never missed a chance for a bit of fun. We were at Plymouth Station and were walking towards the cabin before taking over a down train. As we walked along the platform there was a chap reading a broadsheet newspaper. Ron whispered to me, “Don’t look back.” Of course I did, only to see the newspaper in flames. Ronnie had been lighting his pipe and had casually lowered the lighter to touch the newspaper. I’ll never forget the look on the man’s face as his newspaper went up in flames.

The story of cooking a breakfast on a fireman’s shovel is absolutely true and on one occasion we found that ours was missing or broken, I forget which. Anyway, my driver said you’d better go and get another one. I returned with a shiny new shovel and he looked at it and said, “That won’t do.” It was painted and, of course, it would taint the bacon and eggs. I soon found an old one and breakfast was soon ‘on the go’.

One situation which didn’t involve me was at Largin signal box in the Glyn Valley, between Bodmin Road and Doublebois: it was known as the loneliest box in Cornwall. As trains pass signal boxes it is customary for the driver and fireman to exchange a wave with the signalman. Anyway, on this particular day the driver and fireman, both St Blazey men, decided to have some fun. They wedged the regulator and moved to the side of the engine farthest from the signal box and climbed out onto the steps. The signalman, expecting a wave, saw no one and panic set in. He quickly tapped out the signal for runaway train. Now, that must have been received with puzzled looks as it was going uphill. At the next signal box both men were back in position and determined to give the occupier the usual cheery wave. I imagine that there must have been a very red face in the Largin box.

Some trains arriving in Truro from Paddington had as many as 15 coaches which, when stopped at the platform, stretched out across Carvedras Viaduct. Such trains were a heavy load and needed the assistance of another engine on the rear (‘banking’) to push them up the slope towards Highertown Bridge.

A driver was heading down from Doublebois to Bodmin Road and was travelling far too fast. His fireman, Jack, shouted, ‘Slow down, I want to carry on living,’ to which the driver responded, ‘Well I don’t’. He managed to stop but overshot the station by some distance.

It was important that drivers arrived at work on time and the GWR had a system of knocking them up. Call Boys (engine cleaners working on nights) would be used who would take a push bike from the engine shed, ride to their house and tap on the door or window until they received a response. It was once a rule that footplate staff had to live within a certain distance from the station and Green Close in Truro and Chy-an-Mor in Penzance were the locations of a number of railway cottages.

Steam coal was used in the engine firebox, delivered to the tender by a team of men working on the coal stage using 30cwt trucks. It arrived in all shapes and sizes and one of my duties was to break it to the required size using a pick and then to drench it in water to remove the dust. This was usually done when the driver was off having a cup of tea!

I have been asked how much coal a steam engine consumes but that is difficult to answer. It very much depends on how heavy-handed the driver is and on what sort of coal is being used. There were various experiments during my time but GWR engines were designed to use steam coal and the Welsh Valleys produced the best. As a guide, I reckon we used three to three-and-a-half tons for the 60-mile run from Truro to Plymouth.

One situation which involved me was at Marazion Station. As we approached, I noticed some bullrushes by a pond connected to the Cheshire Home there. My wife was a teacher and I thought they would be a good addition to her nature table. My driver said, ‘Okay, I’ll overshoot the platform and you can jump off and get some’. It sounded like a good plan. All went well until I reached the fence by the pond but as I attempted to jump over it my foot slipped and I was suddenly up to my waist in water. Meanwhile the guard was waving his green flag and blowing the whistle and as I climbed back into the cab, he wanted to know why I was in such a state. I also had to explain what had happened when we arrived back in Truro but I never heard any more about it. And yes, I did get the bullrushes!

If I was on an early turn, perhaps the 6.15am to Newquay, it meant being at work by 5.00am to build up the fire (the night worker firelighters had lit it probably six hours earlier with kindling wood, cotton waste and coal). While I was tending to the fire my driver would be lubricating the various points on the engine. At about 5.50am it was time to leave to collect our coaches. Of course, in winter time it was still dark and we had to use a paraffin flare oil lamp to see what we were doing.

A Paraffin Flare Oil Lamp

A Paraffin Flare Oil Lamp

Every steam engine was different with its own character and everyone was a ‘her’. Diesel engines arrived in Cornwall during the late 1950s and they all seemed the same – devoid of any ‘personality’. I accept there had to be change but the magic of the job disappeared with their introduction. I loved the age of steam and regretted that my involvement in it was so short.

Falmouth Line – The Maritime Line

The Truro to Falmouth broad gauge line was built by the Cornwall Railway Company and opened in 1863. It was subsequently converted to standard gauge in 1892.

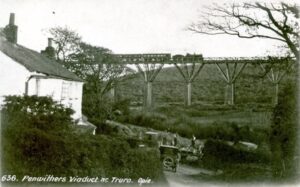

The Penwithers Viaduct in 1924 before it was re-formed as an embankment

The Penwithers Viaduct in 1924 before it was re-formed as an embankment

A Broad Gauge train arriving at Perranwell Station pre-1892

A Broad Gauge train arriving at Perranwell Station pre-1892

Falmouth Docks

Falmouth Docks

Later, you will read that we were not allowed to cross a white line as we approached Newham Gas Works. A similar situation applied here when our goods wagon had to be taken over by a Falmouth Docks engine.

Newham Line

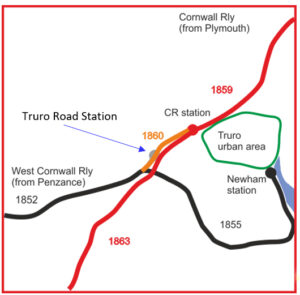

I hesitate to call this a branch line as it was once Truro’s main station and how great it must have been to alight next to the river, albeit mud a lot of the time. It was Truro’s second station – the first, Truro Road, was where indicated on the image below.

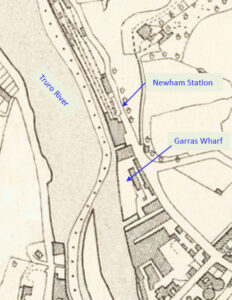

In 1855, the West Cornwall Railway Company extended the standard gauge main line from the west to a new terminus at Newham. It remained a passenger service for just eight years and a goods service until 1971.

The Newham line was steep and goods trains had to stop a part way down to set the wagon brakes. This was down to the driver’s judgement and the brakes would be set and a securing pin inserted. In addition, there were the locomotive brakes and the brake wheel operated by the guard.

One problem we had at the terminus was with the wagon axle boxes. These were made of wood and metal which was fine when they were lubricated with grease but when it was changed to oil, a problem arose. The system of unloading was to tip the wagons but as they were turned, the oil ran out requiring constant re-filling. A reversion to grease quickly overcame the problem.

Newham circa 1960 with the railway and station buildings still in place

Newham circa 1960 with the railway and station buildings still in place

Newham Station

Newham Station

Since the building of the new gas works in 1955 there were regular deliveries of coal until its closure in 1971. The gas works were located on a short branch and on the approach, there was a white line which our engine could not cross. Once stationary, the wagons were unhooked and allowed to travel the remaining distance by gravity. It was usually a full load for the All Purpose 4500 class steam tank engines with loaded wagons in and empties out, with the empty wagons pushed up to the white line by the gas works staff and re-connected to our engine.

Truro gas works from across the river

Truro gas works from across the river

The gas works siding – in use from 1955 to 1971

The gas works siding – in use from 1955 to 1971

Apart from deliveries to the gas works, the main goods at the station was coal for local merchants and Fyffe’s bananas.

Joey Sweet was a shunter at Newham during my time

Joey Sweet was a shunter at Newham during my time

Steaming up the incline from Newham in the early 1960s

Steaming up the incline from Newham in the early 1960s

Chacewater to Newquay Line

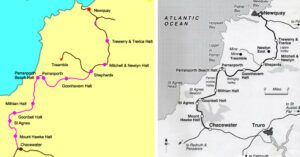

The route from Chacewater to Newquay

The route from Chacewater to Newquay

Having been born in St Agnes, this line is, or was, close to my heart and I hope I’m forgiven for making it the longest section in this article.

The line was about 19 miles long and was opened in two stages; Chacewater (Blackwater junction) to Perranporth on the 6th July 1903 and Perranporth to Newquay (via Tolcarne junction), on the 2nd January 1905. I often think of those who witnessed the sight of smoke rising from the cuttings for the first time. People in our villages could now travel to any place in the country linked by steel rails providing of course, they could afford the fare.

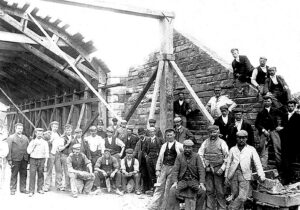

A great number of people came to Cornwall to help build the railway. The route included many hills and valleys and it must have come as quite a relief to the navvies when they came across a length of level ground.

It was constructed in accordance with the Great Western Railway Act of 1897 and provided a valuable service to both locals and visitors from 1903 to 1963.

The branch line left the main line west of Chacewater Station on a curving right hand embankment and crossed the road at the west end of Blackwater. The stone from the excavations was transported on horse-drawn wagons on temporary tracks to build the embankments. The wagons used were fairly wide and short so that when loaded they would tip easily. As the distance between the cutting and the embankment increased, a steam locomotive was used to haul the wagons until a horse was again attached for tipping. The men working on the line used picks, shovels and wheelbarrows. These were navvy barrows, quite different to the long, thin type used locally at the time. Navvy barrows were short, wide and shallow and would tip easily and their ease of use appealed to the local builders who have used them ever since.

The first train left Chacewater Station at 9.30am on the 6th July with families and groups of school children. Many more joined it at St Agnes and the passengers must have been excited to see people cheering as it passed along its route. It was met by the sound of detonators at St Agnes and Perranporth stations where the buildings were gaily decorated with bunting.

In the first Journal of the St Agnes Museum Trust, John Redfearn described the line. “It started at Blackwater East on a fairly sharp curve of one furlong, two chains radius, which, incidentally, apart from a similar one at Perranporth, was the most severe on the whole route. It then continued in a northerly direction from Blackwater Junction up a steep gradient of 1 in 60 for six furlongs, under the road at Hellenbeagle Bridge where a road diversion was necessary, then falling 1 in 60 it came to Mount Hawke Halt, 1½ miles from Chacewater Station.” (1)

“Mount Hawke Halt was below a road bridge on the Chiverton to Mount Hawke road and was in keeping with many of the stations and halts on the branch line in that they were some distance from the villages from which they took their name, somewhat surprising in view of the purpose of the halt, a GWR invention, which was to bring the railway as close as possible to small communities. From Mount Hawke the railway continued on its northward journey all the time rising, first at 1 in 60, a curve to the left then right, past Gover Farm, under the road at Sandy Lane crossroads and out on to the embankment on the approach to St Agnes Station, where the gradient was a rising of 1 in 182. Almost ahead, on the left, the passenger would have a grand view of the Beacon dominating the sea and countryside all around at 640 feet above sea level and the village of St Agnes lying below it to the north east.” (2)

By 1905, the entire length was in use but all was not well as one St Agnes newspaper correspondent despaired at the management of the train service on the Newquay to Chacewater line. He observed that passengers had to cool their heels while their temperatures rose as they waited for a connection at Chacewater Station. It was a cold spot in winter and he told of their mortification at seeing an empty motor train pass through while they waited for theirs. (3)

From memory, I think that there were six passenger trains each way – two that started and finished in Truro and the other four from Chacewater. I guess that this could have varied depending on the time of year. I think the maximum speed for the Branch line was 40mph.

In 1924, an extra platform was brought into use at Chacewater Station and the branch line then commenced from there.

In 1924, an extra platform was brought into use at Chacewater Station and the branch line then commenced from there.

Building Blackwater Bridge over the main A30 road

Building Blackwater Bridge over the main A30 road

The new line was little comfort to the residents of Blackwater; there was no station or halt for them, and they still had to walk to Chacewater or Scorrier to catch a train.

Blackwater Bridge from the west and the reason it was dubbed the ‘Rhododendron Line’

Blackwater Bridge from the west and the reason it was dubbed the ‘Rhododendron Line’

The only remaining sign of a railway in Blackwater is the rhododendron-covered embankment at the western end of the village. The bridge spanning the road was demolished in February 1972 in a fraction of the time it took to build; it had stood for 70 years and its removal confirmed, as if confirmation was needed, that the line would never reopen.

It may come as a surprise to learn that beneath the embankment on the right in the above photograph, the Spread-Eagle public house once stood. One contributor stated that the roof was ‘caved in’ but the walls remained so maybe, just maybe, the bar is still in place!

Claude and Betty Tonkin lived at Railway Cottages, between Mount Hawke and Blackwater. As the name implies, their cottage was adjacent to the railway line. They had an oil lamp suspended from the ceiling and Claude said that it would vibrate as the trains passed.

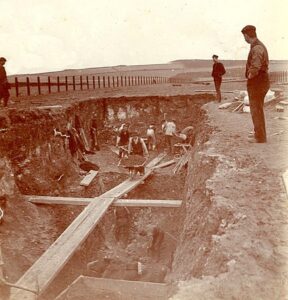

Circa 1900…Mount Hawke Railway Halt being excavated by navvies – no health & safety rules in those days

Circa 1900…Mount Hawke Railway Halt being excavated by navvies – no health & safety rules in those days

Mount Hawke Halt was commissioned on the 16th August 1905 and described in Kelly’s Trade Directory as, “A halting place on the Perranporth and Newquay electric branch of the Great Western Railway.” It opened with a wooden platform and no shelter.

Mount Hawke Halt and heading for St Agnes – by now the wooden platform has been replaced with concrete and the traditional pagoda shelter is in place (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

Mount Hawke Halt and heading for St Agnes – by now the wooden platform has been replaced with concrete and the traditional pagoda shelter is in place (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

I recall one of the drivers over-shooting the platform at Mount Hawke. Unfortunately, a lady wanted to get off and as she was in a coach with no corridor, the train had to back up. Drivers had their markers, some sort of guide as to where to stop the engine so that the coach was in the correct position along the platform. In this case it was a windblown tree on the bank but before the train had arrived, the maintenance gang had cut it down.

Approaching St Agnes Station by way of Schol Bridge which was demolished in 1964/65 (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

Approaching St Agnes Station by way of Schol Bridge which was demolished in 1964/65 (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

St Agnes Station before the 1937 passing loop was built (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

St Agnes Station before the 1937 passing loop was built (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

St Agnes Station with the 1937 passing loop (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

St Agnes Station with the 1937 passing loop (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

I remember there being two camping coaches at St Agnes and that in the 1960s someone forgot to change the points and the train left the station and headed straight on, into the bank just short of Presingoll bridge.

There was usually only one goods train a day on this line and often it had to take twenty-ton coal wagons to St Agnes, Perranporth and Shepherds, for local coal merchants. At St Agnes the merchant was Richie Pearce and at Perranporth it was John Rose of Mithian. The wagons were pushed into a siding and the coal unloaded by hand. The empty wagons were then collected and returned to Truro.

John Eley worked part time for John and Norman Rose and recalls them buying full railway wagons of coal. He said, “On some occasions the wagons were not purpose built and the sides were fixed, requiring the coal to be thrown up over the side and about six feet from the track. A full day’s shovelling was needed to unload them for which I was paid 2/6 (12.5p) per hour in the 1960s. The coal was then weighed into sacks and loaded onto the lorries for delivery.” (4)

Goonbell Halt (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

Goonbell Halt (Photo: courtesy Clive Benney)

Wheal Liberty Viaduct (between Goonbell Halt and Mithian) being built by Arthur Carkeek of Redruth in 1902 using local stone, to a design by James C Inglis. It straddles a small river in a heavily mined valley and is a fine example of railway construction and is aesthetically very pleasing.

Wheal Liberty Viaduct (between Goonbell Halt and Mithian) being built by Arthur Carkeek of Redruth in 1902 using local stone, to a design by James C Inglis. It straddles a small river in a heavily mined valley and is a fine example of railway construction and is aesthetically very pleasing.

Gangers working along the line would often indicate that they could do with some coal for their stoves and I remember one occasion when I waited until the right moment and then kicked out a large piece. Unfortunately, it landed like a bouncing bomb, smashed through the hut door and demolished the stove.

Excavating Mithian Halt

Excavating Mithian Halt

There is a lovely story that John Rose of Mithian delayed the railway contractors a day whilst he scraped off the topsoil from the route of the track across his fields. After all, ‘topsoil is as dear as saffron!’

The Halt opened in August 1905, a couple of years after the line was brought into use. An entry in Kelly’s Directory in the early 1900s read, “The Great Western Railway motor car service from Chacewater to Newquay has a ‘Halt’ at Mithian.”

Mithian School was closed for the opening of the Halt and the children were given a free ride to and from Perranporth. (5)

During the Second World War, many servicemen were billeted at the top of Piggy Lane (and elsewhere) and it became a familiar sight to see them walking from Mithian Halt and up through the village to their temporary home.

Mithian Halt (Photo: courtesy Angie Harrall)

Mithian Halt (Photo: courtesy Angie Harrall)

John Flanagan of Mithian recalled travelling the line in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He said, “One of the guards always wore a rose in his lapel and he would ask me to turn out the lamp as I left the Halt.”

At the closure of the line, in 1963, the guard on the last train turned out the one remaining oil lamp: the other one had been stolen a week earlier, presumably as a souvenir. On this occasion though, instead of leaving the light in position, he removed it and took it onto the train.

The Halt at Mithian was just beyond Montrose Farm but little sign of its existence remains although the slight dip in the road is a clue.

From Mithian the railway ran down through Perrancoombe, crossing Blowing House Bridge and on towards Perranporth. It was an easy run but the return trip often presented a problem as Edward Ely of Trevellas explained. “The incline from Perrancoombe to Mithian was steep and you could hear the engines slow as the workload increased. On Bank Holidays there was always a full load and we would listen to the engine as it struggled to make the top. On some occasions it would come to rest on the bridge which meant a long wait while an additional engine was brought out from Truro.” (6)

Perranporth Beach Halt from where the platform was removed and re-used at The Dell, Falmouth

Perranporth Beach Halt from where the platform was removed and re-used at The Dell, Falmouth

The approach to Perranporth Station

The approach to Perranporth Station

The station had a subway and the railings can be see to the right

The station had a subway and the railings can be see to the right

Perranporth Station looking up through Bolingey Valley

Perranporth Station looking up through Bolingey Valley

Goonhavern Halt, now long gone but the chapel on the right helps to identify its location

Goonhavern Halt, now long gone but the chapel on the right helps to identify its location

During the late 1950s to its closure in 1963, John Eley worked as a maintenance man on the Blackwater Bridge to Goonhavern section of the line. He recalled his interview and medical in Plymouth. “It involved looking through a pair of very old and battered spectacles and being asked if he could see anything. I replied, ‘Not a thing’ and was told, ‘You’ll do’. There were five men working on this stretch of track and a further four to cover Goonhavern to Newquay. During the summer months we were kept busy trimming the banks and hedges bordering the track and I recall many fires caused by the sparks and clinker being blown out by the steam engines, particularly the older models. It often set fire to the fencing and the fields of corn alongside the track and compensation had to be paid to the farmers. It was also necessary to maintain the track and we worked on this for about four months in the year. This involved loosening the chair bolts, unbolting and oiling the chairs, winding down and tightening the bolts. It was also necessary to oil the slotted fishplates at the junctions of the tracks lengths and I painfully remember this was a favourite place for nesting wasps. Our transport consisted of a motorised trolley which ran along the railway track. It had a one-ton capacity, was powered by a Ford V8 engine and was designed to carry six to eight people. There was, of course, no need for a steering wheel but it had a number of gears that were used in either forward or reverse mode. It carried its own derailing equipment to enable it to be removed from the track very quickly although there was a very efficient alerting procedure that ensured that we would not be mown down by the next train. There was also a small two-man version available and this could be lifted on and off the tracks by its wooden handles. One rail was always higher than its partner, even on flat stretches. This may only be by half an inch but was sufficient to keep the bogey wheels running true. On corners there may be a difference of four inches and with the arrival of the longer diesel units a lot of damage was caused to the rails as they negotiated the relatively tight bends. During the winter months it was necessary to check and build up any lengths that had dropped in level. Siting boards were used to check the height and the ballast had to be removed to enable the sleepers to be packed up. The ballast was shovelled back onto the sess (a footpath made from ashes) and chippings barrowed from the stockpiles along the edge of the track. A special cup was used to measure the quantity of chippings required as determined by the siting process. The chippings were spread under the raised sleeper and the next passing train would compress it.” John enjoyed his time on the railway and regretted its passing. (7)

Shepherds Station in 1958 (Photo: courtesy of Colin Retallick)

Shepherds Station in 1958 (Photo: courtesy of Colin Retallick)

Roy Leverton was driving a 45 Class steam engine and as we left Shepherd’s Station, he told me to put his can of soup on the fountain (steam pipes set at high level in the cab). I did as I was told and when we reached Newquay, he reached up to retrieve the piping hot tin. Roy said, “You silly bugger, you haven’t made a hole in it.” He took out his knife and stabbed the lid. It exploded and his dinner went everywhere. We had hot soup dripping on us from the cab roof and Roy having a go at me. I responded by saying that he shouldn’t have stabbed it but, of course, I wasn’t going to change his mind about it being my fault.

The track bed between Shepherds and Mitchell was later put to good use by the Lappa Valley Railway, a 15-inch gauge railway.

Beyond Mitchell and Newlyn Halt was Trewerry and Trerice Halt and this 1922 photo shows the wooden platform, later replaced by concrete

Beyond Mitchell and Newlyn Halt was Trewerry and Trerice Halt and this 1922 photo shows the wooden platform, later replaced by concrete

At the end of the line was Newquay Station, opened in 1876 by the Cornwall Minerals Railway

At the end of the line was Newquay Station, opened in 1876 by the Cornwall Minerals Railway

All things come to an end and sad to say that applied to the Chacewater to Newquay line which closed in 1963. There were many who had relied on it and mourned its demise. Its history is quite short, just sixty years, but during that time it had served the local populace, provided jobs and delivered many holidaymakers to their destination. With indecent haste its track was removed, halts destroyed and cuttings filled. Local historian Tony Mansell said, “In our book, Blackwater and its Neighbours, we wrote that the line was shut by the Beeching axe but it seems we were wrong, it closed just before he began his savage cuts but I still think he had a hand in it.” There are still many features to remind us of its route, the bridges, viaducts and the scars across the countryside but now we are left with little more than our memories and perhaps some anger at a lost opportunity.

In 1963, I attended a diesel driver course in Swindon but by then I was completely disillusioned. The loss of the beloved steam engines had hit me hard and the savage Beeching cuts had demoralised the entire industry and men were leaving in droves. I have never known a man’s name to be met with such antipathy as Robert Beeching: it was no exaggeration to say that he was hated.

I chatted it over with Hilary and we agreed that it was time for a change of direction. I applied for a job as an Order Man for Harvey & Co and was accepted. The following day I delivered my resignation letter, fully expecting to be met with reasons why I should remain with the Railway. Instead, I was simply told to put it in the box with all the others.

Unfortunately, even though I had passed the examinations, I left before I had gained sufficient practical experience to qualify as a driver. Hence the title of this article.

Pat at the controls of a diesel engine

Pat at the controls of a diesel engine

I’ll finish with an anomaly. Time-keeping is important and a watch is provided for the guard but not the driver and when a driver retires, what do they give him? A watch!

End Notes

- The first Journal of the St Agnes Museum Trust

- Ibid

- Royal Cornwall Gazette of the 30th of November 1905

- Mithian in the Parishes of St Agnes and Perranzabuloe by Tony Mansell (ISBN 0-9545583-0-8)

- Mithian School Log

- Jericho to Cligga by Clive Benney and Tony Mansell (ISBN 0-9545583-6-7)

- Mithian in the Parishes of St Agnes and Perranzabuloe by Tony Mansell (ISBN 0-9545583-0-8)

Hilary and Pat Nankivell

Hilary and Pat Nankivell

This article has its beginnings in a talk I delivered to the Perranporth and St Agnes Probus Club of which I was a member. I have enjoyed recalling the events and stories from my railway career which was so enjoyable for me.

Added to my memories are a few extracts from a number of local books by Clive Benney and Tony Mansell and I appreciate being able to include them here.

There is just one other thing, writing this article has given me the opportunity to remind everyone that the father of the Railway was Richard Trevithick, not George Stephenson!

Thank You Tony.

I enjoyed reading the articles and have forwarded it to members in St Ives for them to read.

Now I know how Barry West knows you all so well!

Val

Thanks Val.

Interesting story, Tony. I had very little to do with the railway because I failed my 11plus exam!! I lived in Mithian at the time and if I had passed my 11plus I would have had to catch the train each day to attend Grammer School in Truro or Falmouth, I can’t remember where. Instead, I had to cycle back and forth to St Agnes every day.

I remember being very disappointed, not at failing the exam, but because my girlfriend at the time passed and we went our separate ways, so to speak.