This is a captivating Cornish Story of a group of treacherous rocks that have sunk over a thousand ships. It weaves together stories of shipwrecks, engineering failures, and remarkable triumphs, focusing on the challenges faced in constructing the four iconic Eddystone lighthouses, the last of which still stands as a beacon against the unforgiving sea.

For centuries, ships navigating the English Channel would hug the French coast to avoid the dangerous Eddystone rocks. In 1620, even the captain of the famous “Mayflower,” Christopher Jones, described them thus, “A wicked reef of 23 rust red rocks lying nine-and one-half miles south of the Devon mainland, great ragged stones around which the sea constantly eddies, a great danger to all ships hereabouts, they sit astride the entrance to this harbour.”

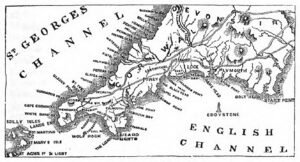

A map showing the Eddystone reef’s precarious position in the English Channel

A map showing the Eddystone reef’s precarious position in the English Channel

The rocks, known as the “Eddie stones,” are located 14 miles south of Plymouth, lying in the fairway to the port of Plymouth and its historic Naval Dockyard. These submerged rocks are positioned roughly in a straight line between Start Point and Lizard Point. They are partially covered at high tide, and the sea breaks over them, creating a heavy swell. In the days before a warning light was installed, mariners often caught a fleeting glimpse of a flash of white from the waves crashing over the rocks at night, followed by their vessels being dashed to pieces against the hard granite. Before the light was erected, an average of 50 vessels per year were lost to the reef, sent to Davy Jones’ locker.

The first attempts to get a warning signal came in 1665. Sir John Coryton asked permission to keep a coal fire burning on the Eddystone rock, but nothing seems to have come of the proposal.

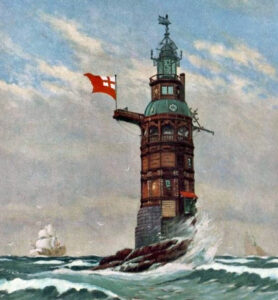

Eddystone Lighthouse Number 1

Winstanley’s lighthouse 1696-1703

An artist’s impression of Henry Winstanley’s Eddystone Lighthouse

An artist’s impression of Henry Winstanley’s Eddystone Lighthouse

The first lighthouse on this rock was initiated in 1696 by Henry Winstanley. It was the world’s first offshore lighthouse. An elaborate wooden structure resembling a kiosk, it was described by a contemporary critic as looking like a Chinese pagoda, featuring open galleries and fantastical projections. It was anchored to the rock with 12 iron stanchions. Contrary to popular Victorian belief, Winstanley was not a ship owner with a personal stake in the project, nor had he suffered the loss of two ships on the reef. He financed the whole venture himself, at a cost of £8,000, which was a considerable sum at that time. He had created a ‘House of Wonders’ in his home village of Littlebury, Essex, filled with perpetual motion machines, mechanical servants, and clockwork ghosts to raise funds. Winstanley eagerly got to work, and by the end of the first summer had constructed a solid stone tower 40 feet high, topped with an unusual wooden structure. This addition, complete with intricate carvings and decorative ironwork, brought the total height to 80 feet.

During this time, England was at war with France prompting the Admiralty to assign a guard ship to protect the workforce on days with suitable weather for accessing the rock. On one such morning in June 1697, the guard ship did not arrive. Instead, a French privateer unexpectedly appeared. Furious, Winstanley shook his fist at the low, sleek French frigate that had approached undetected close to the rock. The builders were in no position to resist, and after a brief hand-to-hand encounter, Winstanley and his men were taken aboard the privateer. The privateer then fired several cannon shots at the lighthouse’s foundations before sailing off to St Malo, France. Within a couple of weeks, the British Admiralty received a brazen demand for a ransom of £1,000. At the same time, a dispatch from the unfortunate inventor was received, in which he warned their lordships of a most uncomfortable time unless they secured his release to complete his works on the Eddystone Reef before the autumn gales.

Later, they were returned to England in exchange for some French sailors who had been captured by an English ship, a common practice in maritime operations of that era. Louis XIV later stated that although he was at war with England, he was not at war with humanity or the entire world. Thankfully, the men were released and allowed to continue their work. Unfortunately, they landed at Portsmouth rather than Plymouth, thus delaying him further. Although he soon got back to the rock to recommence construction.

Despite grave warnings, Winstanley was determined to try his handiwork, although the lighthouse was merely an empty shell. On the night of November 14th 1698, mariners making for Plymouth were astounded to see a light burning high up on the perilous Eddystone rock, a light provided by a gallery of 40 candles.

The tower survived the first winter but soon required repairs. Waves frequently washed over the lighthouse, completely obscuring it. The following year, the octagonal tower was expanded into a 12-sided structure, becoming even more ornate.

Winstanley vowed to be in the lighthouse during the worst storm the area had ever experienced. On November 27th 1703, he got his wish. The Great Storm is still regarded as one of the most severe to have struck the southwest coast of England. The next morning, there was no trace of the lighthouse. Tragically, neither Winstanley, the lighthouse, nor its keepers survived the ordeal. Despite losing the lighthouse and its crew, no other ships were wrecked during its brief operation which stands as a testament to Winstanley’s determination.

After the tragic collapse of Winstanley’s lighthouse, and before another could be constructed, the ship “Winchelsea,” a Virginiaman, carrying tobacco, was wrecked on the reef, resulting in significant loss of life. All souls on board perished.

Eddystone Lighthouse Number 2

Rudyerd’s Tower 1709-1755

Captain Lovet subsequently obtained a lease of the rock from the Trinity House Corporation and enlisted John Rudyerd, a silk merchant from London, to build a new lighthouse. Rudyerd’s design was remarkably clever; it was to be built on a base of squared oak timbers laid lengthwise and reinforced with courses of granite. The structure would rise four stories above the rock, reaching a total height of 92 feet.

Lovett secured a patent charter for a 99-year lease on the Eddystone rock. An Act of Parliament allowed him to charge a toll of one penny per ton for all ships passing by the notorious rock.

The architect of the second lighthouse on the Eddystone rock was John Rudyerd, said to have been the son of a Cornish labourer. This lighthouse was a significant improvement over its predecessor and stood for 46 years. Interestingly, it was not the wind or the sea that ultimately caused its destruction, but rather a fire in the canopy. Disaster struck on December 2nd 1755, when the lighthouse lantern caught fire. The three lighthouse keepers attempted to contain the blaze but were quickly overwhelmed. They were forced to take shelter on the rock for the night. The structure was composed of a solid mass of granite and layers of oak timbers, reaching a height of about 45 feet. It formed the core of a hollow, cone-shaped tower made of timber, constructed much like a ship would be built. Smeaton later remarked that “the whole of the building was, indeed, a piece of shipwrightery.” The granite was quarried at Lanlivery and shipped from Wellington Quay. This area is now in the seaside village of Par.

The outside timbers were held together by iron dogs, great iron stanchions were secured to the rock, and the timbers were caulked with oakum like a wooden hulk. It was 92 feet high, very simple in outline, and was a very effective piece of work, fairly easily kept in repair. However, it burnt down in December 1755. It is said that one of the keepers while trying to escape, accidentally swallowed some of the molten lead falling from the candle holders, and in the Edinburgh Museum is to be seen the piece of lead said to have been taken from the unfortunate man’s stomach after his death – a curious relic to say the least. He was Henry Hall who was 94 years old and he died several days later. At the northern end of Millbay Park in Plymouth, a plaque is set into the pavement as a replica of the molten lead that was taken from his body.

Eddystone Lighthouse Number 3 – 1759-1880

Smeaton’s Lighthouse

In June 1756, John Smeaton began constructing a stone tower inspired by the trunk of an oak tree. He had observed how the trunk was formed and how it withstood the elements. By June 12th, a 2¼-ton foundation stone had been transported to the construction site by the Eddystone boat, a 10-ton boat which was based there and transported worked stones out to the reef. She was called the “Neptune Buss.” All the stones were cut with dovetails that interlocked with their neighbouring stones, and marble dowels were used to secure everything together. This innovative design, along with a device for lifting large blocks of stone from ships at sea to significant heights, was a game-changer. As part of the construction process, Smeaton also pioneered the use of hydraulic lime – a type of concrete that cures underwater, which had been invented by the Phoenicians and perfected by the Romans. This advancement ultimately led to the development of Portland cement and later, modern concrete.

A section of the lighthouse showing the dovetailing of the stones and below, the coin struck to stop Smeaton’s men being press-ganged.

A section of the lighthouse showing the dovetailing of the stones and below, the coin struck to stop Smeaton’s men being press-ganged.

At that time, we were once again at war with France, and the press gang was active. Despite an express exemption issued by the Admiralty, Smeaton’s workers were seized from their vessels while travelling to and from the rock. To address this issue, Smeaton had the image of a lighthouse painted on the main sails of his boats. However, his men were still taken while ashore, until a silver medal bearing the same lighthouse symbol was struck and given to each worker.

I find it quite remarkable that, despite the extensive writing about the Eddystone Lighthouses, very little has been mentioned about Lanlivery, where the moorstone was sourced, or about Par, from which the granite was shipped during the construction of two of the lighthouses on the Eddystone reef.

In connection with them the following is from Smeaton’s journal:

“Visited Fowey. 1756. Next morning, the wind blew hard at S.W., we therefore set out for Lanlivery, about six miles from Fowey, and here we found Walter Treleaven and son, to whom I was directed as the principal people in this district for the working of moorstone. Walter, aged 60, acquainted me that he worked on the stonework for the late lighthouse under his elder brother, Peter Treleaven, who had the contract under Mr. Rudyerd. He informed me that none of the stones used therein were above a ton weight, that they were all cramped with iron, each to its neighbour, and the outside courses to those below; but so that none of the cramps could be seen on the outside; that they were all finished at that place, being tried together upon a flooring of boards, and the cramps let in, and that the cramps were made from a pattern he had received from Mr. Rudyerd.”

Peter Treleaven, aged 80, was still alive, but so infirm and ill that he could not see us. I therefore desired his brother Walter, to ask him a few questions, and particularly whether there was any kind of mortar or cement used in the stone work. It being Mr. Jassop’s opinion, from what he had observed, that there was not, which Peter confirmed; but it seems that neither he nor Walter had ever the curiosity to go upon the Eddystone Rock.

“We then went to see the stone and the way by which it was to be carried down to the waterside to be shipped. The pieces of stone here are, in general, of much larger sizes than we saw at Hingstone Downs and are of a quality much freer to work but will not split so truly as I had before been informed. I saw one stone apparently without crack or flaw, which curiosity prompted me to measure and found it to contain no less than 400 tons.”

Smeaton speaks of all the granite worked as surface stone or moorstone.

“Parr, the place of shipment, is about three miles distant, through very bad roads, and employing carriages, indifferently contrived. In this country, they call ploughs; they were not then in practice of drawing above 1 tons at a time, and to move these, they were obliged to yoke a team consisting of a great many bullocks and horses. The stone here was softer than at Hingstone, easier to work with, yet hard enough for building. We were informed that a great part of the stone used at Westminster Bridge for walking paths came from here. It is of coarse grain, red and with white spar, two inches long, called Dog’s Teeth, whereas the Hingstone was of a smaller and smoother grain, much interspersed with mica (black), or tale, which is one of its component parts.”

A few days later, Smeaton visited Falmouth and Constantine to see other moorstones.

In the end, Smeaton used Lanlivery stone for the chief parts of his lighthouse but was compelled on the score of economy to employ a variety of Bath freestone for much of the interior.

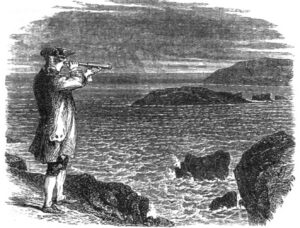

Smeaton looks towards the Eddystone from Plymouth Hoe

Smeaton looks towards the Eddystone from Plymouth Hoe

At the time of shipment, the granite was hauled to Par’s old quay, which at the time was located at today’s Wellington Place. It’s also interesting to know that someone else initially asked Smeaton to design a harbour in Tywardreath Bay (Par) long before Treffry built the harbour there in 1829.

By November 1757, significant progress had been made on the base of the tower. Smeaton concluded the season’s work by being swept out to sea during a north-east gale, narrowly escaping shipwreck and death along the Cornish coast. By the end of the following year, the first eight courses of the tower itself were completed.

Each spring had revealed that the finished portion remained intact, despite being battered by the storms of the previous winter. On Tuesday, October 16th 1759, the light from the twenty-four candles used for illumination finally shone out upon the sea.

The project took Smeaton and his team a total of 3 years, 9 weeks, and 3 days, amounting to 111 days and 10 hours in real time.

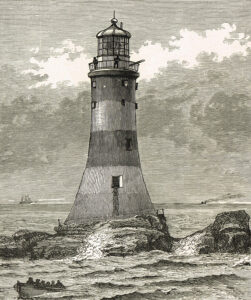

A lovely old illustration of Smeaton’s Tower

A lovely old illustration of Smeaton’s Tower

However, after more than a century of service, the lighthouse was decommissioned in the 1870s due to the discovery of erosion in the bedrock on which it stood. Smeaton’s Tower stood on the “House Rock,” as it was known.

The top half of Smeaton’s tower was dismantled down to 40 feet and re-erected on Plymouth Hoe as a monument to its builder. A catastrophic incident nearly claimed the life of Mr. Douglass, the dedicated engineer from Trinity House, who was overseeing the delicate operation of dismantling the old Eddystone Lighthouse.

During the strenuous task, a crucial chain attached to a towering derrick unexpectedly snapped, sending Mr. Douglas plummeting from an astonishing height of seventy feet. In a fortunate turn of events, he plunged into the churning sea below rather than crashing onto the jagged rocks. As a powerful wave surged toward him, it carried him closer to the perilous rocks. Displaying remarkable resilience, he managed to grasp onto the rocky outcrop and cling there, awaiting rescue from the looming danger.

This restoration and reconstruction of Smeaton’s Tower was funded through local subscriptions and was officially opened by HRH the Duke of Edinburgh in 1882. The remaining bottom part or stump of the lighthouse still stands on Eddystone Rock today.

Eddystone Lighthouse Number 4 – 1882 to present

Douglass’ Lighthouse

James Douglass designed the fourth and current Eddystone Lighthouse, drawing inspiration from the developments of Robert Stevenson and the techniques of John Smeaton. Stevenson had built the famous “Bell Rock” lighthouse at Aberdeen.

Born in London in 1826, James Nicholas Douglass was the eldest son of civil engineer Nicholas Douglass. His brother, William, collaborated with their father on the construction of the Bishop Rock Lighthouse. In addition to the Eddystone Lighthouse, Douglass was responsible for designing several other significant lighthouses, including Southwold, Smalls, Hartland Point, and Souter Lighthouse.

In April 1879, the new site, on the South Rock, was being prepared during the 3½ hours between ebb and flood tide. The supply ship “Hercules” was based at Oreston, now a suburb of Plymouth, and the stone was prepared at the Oreston yard and supplied from the works of Messrs Shearer, Smith and Co of Wadebridge. Due to inclement weather, the foundation stone ceremony for the new Eddystone Lighthouse was postponed from June 21st 1879, to August 19th 1879. When the weather finally improved, His Royal Highness, the Duke of Edinburgh, departed from Falmouth aboard a vessel called the “Lively,” accompanied by the Duchess. They steamed east toward the Eddystone, where the Royal party was greeted by Mr. Douglass, the chief engineer of the lighthouse.

First, they visited the old Smeaton lighthouse located on House Rock. Then, they proceeded to the new building, where the workmen were preparing to place the final stone on the cornice of the tower. This task was performed by the Duke, who laid the foundation stone of the building to rapturous applause.

The progress on the new Eddystone Lighthouse was slow. During the first year, only 135 hours of work could be completed on the rock due to the weather, despite making the most of every opportunity. If the work had stopped at the same height where Smeaton’s lighthouse began, the number of hours worked would have increased by twenty times.

1882, James Douglass’s new Tower to the left and John Smeaton’s old Tower to the right, the photograph was taken at low tide

1882, James Douglass’s new Tower to the left and John Smeaton’s old Tower to the right, the photograph was taken at low tide

The reason for this was the need to construct back dams, which allowed the workers to spend as much time as possible on the foundation. When the sea receded from the dams, water was pumped out using steam power from a floating engine positioned 120 feet from the rock. This enabled the men to work inside the dam until the water overflowed again. Douglass mentioned at the time, “If the work continues this year as it has over the past six months, the base of the tower will be above high tide levels by January, and the main difficulties will be resolved.”

The tower comprised nine floors, not including the lantern. Several of the lower rooms were designated for storage and oil, while the upper levels housed the kitchen and living room, bedrooms, and a service area.

The light was first activated in 1882 and remains in use today. In 1982, it became the first offshore lighthouse operated by Trinity House to be automated. The tower has been modified to include a helipad above the lantern, which was constructed to provide maintenance crews with access. The helipad has a weight limit of 3,600 kg.

A fixed white light emanating from a room on the eighth story signalled the offshore reef of Hand Deeps. This reef is located approximately 3½ miles to the northwest of the Eddystone. Today, there is a secondary fixed red light visible for 13 miles displayed from a window about halfway up the tower.

Two massive bronze bells, each weighing two tons, were placed on either side of the gallery as fog signals, their resonant tones guiding passing vessels through the mist. About ten years later, an explosive fog signal was introduced for a more powerful auditory warning in thick fog. By 1904, the old lamps had given way to the modern marvels of incandescent oil vapour burners, illuminating the way with a brighter glow. Then, in 1959, the lighthouse took a giant leap into the future when it was electrified, marking a new era of brilliance at sea.

Following the construction of the fourth Eddystone Lighthouse, Douglass was knighted and in 1887, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He died in 1898 at his home on the Isle of Wight, and a memorial can be found at St. Boniface Church in Bonchurch. His grave was later relocated to the family plot at St. Petrox Church in Dartmouth.

Sadly, lives have been lost at the Eddystone – an officer and six Trinity House men died whilst trying to deliver gear.

The tower is 49 metres (161 ft) high, and its white light flashes twice every 10 seconds. The light is visible to 22 nautical miles (41 km) and is supplemented by a foghorn of 3 blasts every 62 seconds.

Today, the steadfast light continues to guide mariners safely through treacherous waters. Even in an age dominated by advanced technology, one cannot afford to take such a vital beacon for granted. It stands proudly as a luminous sentinel, illuminating the night sky and serving as a poignant memorial to all those who have met with tragedy in these waters throughout the centuries. Long may its radiant glow burn brightly, offering hope and direction to those who navigate the English Channel.

Lyndon Allen

Lyndon Allen

Lyndon Allen grew up in Charlestown, St Austell. He comes from two longstanding historical families in Charlestown, who have been an integral part of village life for over 230 years, particularly in its maritime heritage. Lyndon attended both Charlestown and Penrice schools before leaving in 1981. He pursued a career in the commercial fishing industry, working from the port of Charlestown for thirty-six years, in line with his family’s strong connection to the sea. He retired from the fishing industry in 2019.

Currently, Lyndon operates the award-winning Charlestown Walking Tours, a business he established after the lockdown. He is also an author, a passionate historian, and manages eleven Facebook historygroups, including the popular St Austell History Group. Lyndon has authored four comprehensive history books: two on Charlestown’s history, one on St Austell’s history, and a maritime history book about the St Austell and Mevagissey Bays.

His books are available for purchase on his website at www.charlestowntours.co.uk

Very interesting article and an even more interesting evening at St Austell Old Cornwall Society last month when Lyndon gave this presentation. Absolutely amazing and can certainly recommend this talk.

My great grandfather, Sir James Douglass, is best known for the current Eddystone and Bishop Rock Lighthouses which he designed and was assisted by his eldest living son William Tregarthen Douglass, a great uncle. He was knighted following completion of the Eddystone in 1882. William Tregarthen dismantled the previous lighthouse built by John Smeaton above the base, leaving the stump, and re-erected it on Plymouth Hoe where it stands today.

A book “The Douglass Lighthouses Engineers” includes descriptions of these lighthouses.