Cligga Mine

Cligga Mine

Cligga Head (Kleger in Kernewek) is just over a mile to the south-west of Perranporth, a granite mass projecting about 300 feet above sea level. Located on this promontory is Cligga Mine. In 2006, Clive Benney and Tony Mansell wrote their book, Jericho to Cligga, and some of the information included about the mine has been incorporated here.

Many sources describe Cligga Mine as one of the oldest in Cornwall. It is known to have been worked for a few hundred years and some suggest that its history may extend to a couple of thousand years.

Whatever its age, the mine certainly has a long history and without the aid of modern techniques, the ancient miners simply identified the metallic veins on the cliff face and began tunnelling along the route of the lode. John Gribble, of whom you will read more later, recalled being told that the ore was thrown into piles, probably on cowhides, and dragged out of the workings.

Heritage Gateway includes this information about the mine:

Cligga Head mine was an open cliff work producing tin and wolfram. In 1825 the Wheal Prudence setts, together with Cligga and Perran Great St George, were purchased and worked by a London company called the English Mining Association.

The mine is located by Hamilton Jenkin and details are given by Dines. Extensive remains are visible on air-photographs, including open works, buildings, shafts and spoil tips.

The views enjoyed by the ancient miners – and by us today

Down St Ann’s Way

Down St Ann’s Way

Over Perran

Over Perran

And out to Cow and Calf

And out to Cow and Calf

In common with this stretch of coastline, the cliff face at Cligga is stained by minerals leeching out from the fissures and adits which drained the mines down to sea level.

From The metalliferous mining region of south-west England by H G Dines

Old men’s (1) levels in the cliff face in search of tin are common in the northern part of the productive area.

Adits and Portals – rockslides have exposed some of the mine workings in the cliff face; these can be reached by climbing up through the mine.

Adits and Portals – rockslides have exposed some of the mine workings in the cliff face; these can be reached by climbing up through the mine.

The surface landscape, too, is littered with reminders of the past: the mining activity, the explosive factory and the adjacent Second World War airfield.

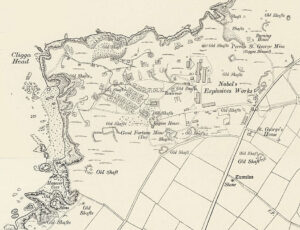

Cligga Head from OS 1888-1913

Cligga Head from OS 1888-1913

The mine workings are located on the cliff edge at Cligga Head and accessed through an adit at beach level.

The mine workings are located on the cliff edge at Cligga Head and accessed through an adit at beach level.

A New Chapter at Cligga

In his book, Perranporth and Perranzabuloe Parish, Bill Trembath states, The high cliffs were once worked by primitive shafts and tunnels but the mine has a more recent history: it is that more recent history which is the main thrust of this article.

Shortly before the Second World War, Captain Tobias Gribble and Raymond Rogers, both of Chacewater, set up Cligga Wolfram & Tin Mines Ltd and began work under licence from the Duchy of Cornwall.

Tobias Gribble was born in 1876 – in Chacewater. That village had been the family home since the 1700s. Tobias has been described as, “A Cornishman and a miner of great experience who discovered that he could not keep out of mining even after his retirement, and therefore interested himself in what is to be found at Cligga Head”. Tobias began his mining career at the age of 14 and worked in mines all over the world, acquiring a considerable reputation as a mining captain and entrepreneur. He was also a prominent local preacher and between 1899 and 1957, when he died, he had delivered over 2,200 sermons.

In 1938, ore was being raised at Cligga and taken to Perrancoombe where it was processed. In the following year, the Rhodesian Mines Trust Ltd became involved and work progressed down to sea level.

In 1939, The West Briton reported:

The work at Cligga Head is particularly interesting in that the entrance to the mine is at sea level, at the base of the cliff. Tin and wolfram are being recovered, and the miners go to work down the vast side of the cliff, scrambling and sliding their way to the gaping mouth of the adit at the foot. Dotted above them, all over the great height of the old cliff face, stare the adits bored by the ‘old men,’ and at one spot, where the cliff has fallen away, in the course of ages, is revealed the semi-circle of an ancient shaft.

1939 – Cligga Mine surface workings.

1939 – Cligga Mine surface workings.

In October 1941, the West Briton reported:

The prospectors started on the side of the steep cliff by driving into old shafts and workings, and found sufficient indications of the presence of tin and wolfram in considerable quantities to warrant the commencement of mining operations on a small scale. The small shaft from which the number one level, about 100 feet from surface, was being developed, was sunk a further 100 feet to the number two level, where it was communicated with a drive, (2) approximately 400 feet long, brought in from the face of the cliff. That connection permitted all hoisting to be concentrated in the shaft to the exclusion of the inclined skip road down the face of the cliff…The massive head-gear, which until recently stood at Polberro Mine, St Agnes, has been transferred to Cligga, following suspension of operations on the former property, and re-erected…The shaft has been sunk about 300 feet to sea level and connected with three galleries about 600 feet in length leading out to the cliff edge.

Matchsticks holding back mountains.

Matchsticks holding back mountains.

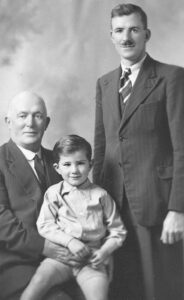

Tobias Gribble’s grandson, John Gribble, said, “When he [Tobias] was working Cligga during the Second World War he decided that the entire family would live in one of the buildings there. Not the safest place I suppose, with the airfield next door, but at least we were all together. My father, Carlos Gribble, was the mine surveyor in 1942 and I was about three years old.”

Three generations – Tobias, Carlos and John Gribble who all worked at Cligga Mine. (Photo: courtesy John Gribble)

Three generations – Tobias, Carlos and John Gribble who all worked at Cligga Mine. (Photo: courtesy John Gribble)

Arnold Hodge was the Mayor of Truro in 1969/70 and Freeman of that City in 1987. He worked at Cligga and not long before he died, he talked to Clive Benney about his time there.

An Interview with Joseph Arnold Hodge

“Well now, World War Two came but even before that, everybody knew that something was going to happen sooner or later, particularly in the late 1930s. Hitler was on the go and showing his teeth to everybody. They started to look around for businesses to make war-heads and various other things: you’ve got to have the stuff for it and the only place was Cornwall. Groups of miners who had very little money, even if they had jobs they didn’t get much, used to go to these old mines and work what we called hard labour – by beating the drill with a hammer and breaking the stuff out. They took it away to a firm called Stewarts at Portreath Road – where the Gold Centre is now. They would buy it and process it – the miners had no way of processing it themselves at first but later there was a waterwheel stamps and a table down at Perrancoombe and by doing it there, with water nearby, they could deal with it themselves.

Cligga was a rich little mine; they would get out wolfram which was very highly sought after, for guns and warheads. By this time the war had started and what we couldn’t get from Cornwall, we couldn’t get.

The Government decided to use East Pool, it was a very large mine but beaten out and was going to close because they couldn’t keep going with what they were getting out. The Government said, ‘Right, we’ll pay you so much a ton for all that you produce and that’ll help you to keep going’. And it did – until the early 1960s.

Captain Gribble and a man called Rogers had opened up Cligga. To start with, when I went out there first, they had a single skip road – that’s one skip going up and down – and they were down to about 100 feet, that was the shaft we were working in. Other shafts were deeper but the one that they wanted to work was about 100 feet deep. It was a successful little mine so they decided to sink a further 100 feet to about 200 feet. The sea level was about 300 feet below the top of the cliff. Now, the problem of Cornwall as a mining county will always be water – it cost a fortune to get it out. Our strata makes a tremendous amount of water: you couldn’t put an ordinary little pump in, it needed a Cornish pump. But at Cligga we had 300 feet that would drain itself – straight into the sea. That meant that they didn’t go any deeper than 300 feet apart from a little sump.

We had to have water for the steam engine. You can’t use salt water for a steam engine – it’ll rust out – but you can use it for a lot of other things like tin dressing and suchlike. So, what they did was, down on Cligga Beach, they built a pumping station and that pumped up water to a very large concrete tank and the salt water was used for general purposes throughout the mine.

There are three tunnels that drain the mine – one from each level – 100 feet, 200 feet and 300 feet down the cliff face, the bottom one was near enough at sea level.

Now, we still had to have fresh water and when I went out there first there was an old man who lived out Trevellas who used to carry water in a pony and barrel. The barrel was fixed between two cartwheels and he used to bring in enough water to run the steam engine that we had at that time. That was all right while we were 100 feet deep and not producing much. When we got deeper, then we had to have a bigger mill to dress the stuff. They decided then that they would get a steam engine to drive the mill. That required more fresh water so what they did, they went down Coombe, that’s Perrancoombe, and put a ram in and then drove grass – pumped it to the top. It was pumped right up across the fields, up behind St George’s Hotel, across the road, up the factory gates and out to Cligga. There was another reservoir on the other side of the road into the mine and this was used for steam.

By this time I was 17 years old; I’d started at Polberro when I was 14 before going to Cligga. I lived in Chacewater near to Captain Gribble and learnt to drive in his car. I drove him up to Great Wheal Busy Mine – that closed in 1924 and was mothballed and left. Bear in mind that the war was on and you couldn’t go and buy anything new, they had to scour the countryside for disused mines for anything they had left, clean it up, refurbish it, and make it work. Now, we went in the old mill at Wheal Busy to look at a very large engine there. We had an engineer out Cligga that had worked at Wheal Busy, he was a very down-to-earth but brilliant man and he went out with us to see what it would do. Wheal Busy had a caretaker and he was there as well – he was employed by Lord Falmouth. The engine there used oil. Captain Gribble said, ‘Oil! we don’t want an oil engine, we can’t get oil anywhere. It’s rationed and this is going to work 24 hours a day’.

Leonard Barrett, the engineer, said ‘Well, I could convert ‘n Cap’n’.

The top and bottom of it was that they bought the Wheal Busy engine, Barrett converted it, and it worked the two Lancashire boilers which were down over the cliffs. A man called Reg Tremain from St Agnes was the chief engine driver.

Cligga was mostly wolfram, plus a little tin. It was taken by lorry, probably via Truro Station or it may have gone to Perran Station. The mill would work day and night – so would the miners and at the end of each shift they would have a certain amount of clean mineral. That was bagged and put in the tin yard. When we had enough, we would send it up country in a lorry – that was weekly or maybe more often. At that time Cligga was only 300 feet deep. As soon as they went below 300 feet they had trouble – the tide would come in so instead of going deeper, they spread out – back under the aerodrome. If they had gone on any longer they would have had to have gone deeper. It was a lot deeper later, when Geevor opened it up.

A lot of the gear at Cligga, as the mine got bigger, came from Polberro – you couldn’t get new so we had their stuff. The headgear, that’s the one with the wheels on, came from Polberro and they made the shaft into a two-skip shaft and used their skips as well – the gear had previously been removed from Wheal Kitty.

Every summer we ran short of water and there were restrictions put on where the water was cut off for an hour or two a day to save it. Truro Rural District Council was instructed with the task of providing water and the Government was going to pay – this was what Perranporth was waiting for – for years really.

I left Cligga and I believe it closed in 1945. As soon as the war started to turn for the good, they turned their backs on Cornwall again.

The aerodrome was mostly built with horses and carts and a few tractors. The trenches were dug by men in a line so you had to keep going or you’d hold up the others or get a pick up your backside. They took down all the hedges and put in drains. In the early days they were digging a long trench and one bloke was left behind to clean out and a plane came in and knocked his head off – he came from Chacewater and had a large family.

Going in to Cligga, on the right, was the old dynamite factory and on the left, were three houses which are still there. One was lived in and the other two were used to carry out repairs and was where we kept our bicycles and motorbikes.

The RAF considered the Mine to be a landmark – one building stretched for quarter of an acre – it was lit up all night and we had to black out everything which was difficult, with doors opening and men going to and fro from the crusher.

Vic & Tit Trezise worked at Cligga and tin streamed at Trevellas. Vic was a good Cornish hedger and played in St Agnes Band, Tit was a footballer. When I was driving Cap’n Gribble we would often call in to pick up tin from the Trezises. I could never understand how they got so much from that river. Anyway, I found out since – this was the story I was told – that they had some of the mineral rights along the beaches.

When I went out to Cligga first, there was a man called Wilfie Sarre who used to come to work in a Jag. He used to go down over the cliff and pick up stones – when there was a big northerly gale blowing big rocks were washed in, especially in the cove. He would get some clay from where the miners had been walking and roll it around in his hands. He’d push it on to the rock, make a couple of holes and stick a half a stick of dynamite in them, cap it and insert a fuse. The hardest job was to bring the stuff up the cliff face – he used a milkmaid’s yoke with a couple of five-gallon drums and then took it by horse and cart to Jericho Valley stamps. There must be a lot of mineralised rock moving around on the seabed.”

Arnold Hodge talked of using fresh water for the boiler and of how it was first brought to the mine by horse and cart. At one time this was done by Wilfie Sarre’s father who brought it all the way from near Harmony Cot, in Trevellas.

Arnold also spoke of a visit to Jericho Mine where Canadian Sappers were employed to extract precious minerals but his visit with Captain Tobias Gribble had more to do with mining equipment than minerals.

Arnold Hodge and Jericho Mine

“Our Government or the Canadians, equipped them [the miners] and they had everything they wanted and I’m told – I don’t know if it was right or not – that the intention was to drive a tunnel from Jericho Valley right under St Agnes Beacon. The theory was that all the lodes in St Agnes would junction underneath the Beacon. These sappers were out there some time – in the valley on the left of the river.

Captain Gribble said to me, ‘We’ll go into Jericho on the way home,’ so we did.

The mouth of the tunnel was still open; a new tunnel which they had started to drive on geologists’ advice. They had everything: air compressors, track, timber, sleepers… everything. We went into the tunnel – a considerable way in. We had lamps and we could see a lode running across the end, diagonally and Captain Gribble said, ‘Look at that boy’.

I said, ‘It looks all right but what is it?’

He said, ‘It isn’t nothing yet but if I was doing this, and I found that, I wouldn’t stop now’. But the war had got worse and what they did was to take these soldiers to fight – they had to, and that closed the outfit down.

So I said, ‘Well, what are we doing out here, Cap’n?

He said, ‘We want gear don’t we’. And we had the lot, track, compressors, the lot.”

Richie Sandercock, a St Agnes bandsman, began working at Cligga in 1939 – at the age of 15.

An interview with Richie Sandercock of St Agnes

“We worked the mine down to the 300 level, to where it would drain naturally through the adits. I only remember two accidents while I was working there, one was a shift boss who broke both legs and the other was me. We were making a box hole or header, that’s where a vertical shaft is cut up from a level. It may be about 12 feet square and could extend right up to the next level, depending on the lodes. Out of this shaft would be the stopes which were driven sideways – following the mineral. I was making up the timberwork when a large rock fell on my back. They sent out an ambulance from Goonown and Dr Cuthbert Whitworth came out to tend me but I wasn’t badly hurt.

You could always tell when things were going well, someone would start to sing a hymn or a carol and it would be picked up by the men all along the tunnels. George Wills was a good singer but he could lose his cool occasionally. I remember when we had some Russian timber, the stuff was so hard that you couldn’t cut it with a saw and you had to drill holes for the nails. As George was trying to work it, bits of granite were flying off and stinging his arms. He got so fed up that he picked up his hammer and threw it as far as he could. He did this a few times and it was my job to go and fetch it back!

If we were working underground during the day, we could get back to grass (3) by walking out through the adits and up the cliff paths. At night time it was a different matter. We had to climb up the shaft ladders, otherwise enemy planes could have spotted our lights – being so close to the airfield, everything above ground had to be blacked out.

One night a month I had to go on fire patrol and on one occasion I was there with my brothers, Bill and John. We were in the foreman’s office when a German plane dropped some incendiary bombs. Luckily, they were on the edge of the cliff and fell into the sea.

The water for the mill was taken from the sea and one of my jobs was to keep the pump free of seaweed. A lot of us were involved in work that couldn’t be measured and we were paid Daywork, that’s so much a shift. We were paid once a month but you received subsistence each week. The miners worked on contract, that’s measured rates. We had to go to the Count House to receive our pay – where the industrial units are now.”

Stalactites in the making

Stalactites in the making

Cligga Mine staff 1941/42 (Photo: courtesy John Gribble)

Cligga Mine staff 1941/42 (Photo: courtesy John Gribble)

Captain T Gribble and staff of Cligga Mine (Perranporth) April 29th 1942. (Photo: courtesy John Gribble and names by Richie Sandercock of St Agnes – number 85 in photo)

Captain T Gribble and staff of Cligga Mine (Perranporth) April 29th 1942. (Photo: courtesy John Gribble and names by Richie Sandercock of St Agnes – number 85 in photo)

Richie Sandercock also provided these brief descriptions of the various jobs:

- The Grisley Man: breaks up the larger stones until they fall through the grisley – a grill set just below the floor of the level. He also keeps a tally of the number of skips.

- The Skip Man: controls the hoisting of the ore.

- The Machine Man: winds the drill in to the rock face and does the blasting.

- The Mucker: works with a pick and shovel to clear away the rubble following the blasting.

- The Millman: controls the process of the raised ore; he sees it through the crusher, along the conveyor belts, into the bins, through the roller mill and on to the shaker tables.

- The Trammer: pushes the trams.

- The Lander: works at the head of the shaft, he empties the skip and sends and takes signals from below to control the hoisting of the ore.

From the Account Book for Cligga Mines during the Second World War when Captain Tobias Gribble was the manager

Many of the miners came from his village of Chacewater as was the case of Joseph Hodge whose brother, James Angove Hodge, his son Joseph Arnold Hodge, and two nephews and a brother-in-law, all worked at Cligga and whose names and earnings are recorded in this book.

The first pay sheet, number 90, was for the two weeks ending the 16th October 1943 when there were 115 employees as well as a number of contractors. The occupations ranged from Underground Foreman to Labourers. The book covers the period up to 1951 when only a handful of men were employed and the level of pay had changed very little.

Job title and rate per shift:

Underground Foreman, Surveyor, Assayer, Hoist man, Engineman (11/-) , Stoker (11/-), Crusher man (10/-), Mill Foreman (16/8), Millman (9/6 to 12/-) Perrancoombe P. man, Watchman, Labourers (9/6 to 12/-), Fitter (12/-), Millwright (20/-), Carpenter (11/-),

Blacksmith (12/-), Underground shift boss (15/3), Timberman (12/-), Skipman (11/-),

Grizzleyman (11/-), Pipe and trackman (11/-), Miner (11/- to 13/-) and Mucker (11/-).

By way of example, if we take a rate of 11/- (55p) per shift plus a bonus of say £2 produces a gross wage of £8.12 shillings for a 12-shift fortnight. Deducted from this were health insurance two shillings, unemployment insurance one shilling and eight pence, bus service eight shillings, hospital six-pence, and income tax of, say, 10 shillings (variable across the individuals) leaving a net take home pay of approximately £7.10 shillings per fortnight.

Employees: Raymond Leslie Rogers – Underground Foreman, Robert Harvey – Surveyor, Kenneth Pelmear, Wm Henry Gay – Assayer, Edith Muriel Keast, Frederick Osborne – Hoistman, Edward G Smitheram, Reginald Tremain – Engineman, Clarence Andrew, Hugh Nicholls Grenfell, Robert James Caldon – Stoker, James Henry Green, Frederick Wm Edward Halloway, Harold John Knott – Crusherman, Percy John Benney, Hugh Kemp, Bernie Yeo – Mill Foreman, Wm Henry Sandercock, Wm George Martin, Stanley Stephens, Thomas Kellow, John Sandercock, John James R Mannell, Percy Mitchell, Richard John Olds, Fred Samuel Geo. Liuscombe, Wm Frederick Arthur Clark, Richard Fredk Boundy, Nicholas Arthur Hall, Samuel John Tamblyn, Harold Cocking, Stanley Whitford, Wm John Chas. Knuckey, Percival Pascoe, Wm James Robins, Alfred Reginald Crebo, Charles Irwin Roberts, Wm John Retallack, Percy Charles Sandow, Samuel Mitchell, Charles Mitchell, Fredk Geo. Solomon, Cecil Bolitho, John Leonard Tonkin, Robert Henry Berryman, Ernest John Andrew, Henry Spargo, Alfred Bray, Herbert Charles Halloway, Donald Leslie Brede, Peter Davies, Douglas Hedley Vigus, Kenneth Blewett, James Pearson, Stanley Geo. Kemp – Perrancoombe P. man, Robert Keast – Watchman, John Henry Carveth – Labourer, Maurice Stanley G Hicks, James Henry Vincent, Edwin Ernest Lanyon, Wm Glanville Trezise, Stephen Oswald Oates, Charles Hammond, Leonard James Barrett – Fitter, John Charles Lanyon, Wm John Paynter, Leslie Harris, Roythemis Harris, Percival Arthur Benney, Charles Wesley Langford – Millwright, James Rodda – Carpenter, James Hore, Thomas Leslie Dunstan – Blacksmith, Thomas Leslie Jeffery, Hugh George, Peter Arthur John Hardiman, Fredk Arthur Martin – Underground shift boss, Francis Woolcock, George Wills – Timberman, Richard Arthur Sandercock, Thomas Garfield Bawden – Skipman, John Richardson Payne, Fred Palmer, Wm Ralph Dabb – Grizzleyman, John Charles Hutchens, Wm John Davey, Ernest Tripp, Alwyn Leslie Russell – Pipe and Trackman, Crispin Pedley, Wm Henry Eddy – Miner, Andrew Geach, Robert Arthur Coad, James Roy Oates, Walter Gordon Polglase, Joseph Benjamin Jory, Paul Temple Reed, George, Edgar Stephens, Edward Long – Mucker, Norman White, Wm Redvers Downing, Stanley Pellow, Edward John Rashleigh, Wm George Evans, Fred Stanley Tripp Martin, Wm John Pascoe, Thaddens Harris, Cecil John Borlase, Cecil Bawden, Wm Kemp, Wm James Boase, Wm Alfred Truscott, Vivian Harvey, Silas Henry White, Wm Arthur Mills, Nicholas John Grose.

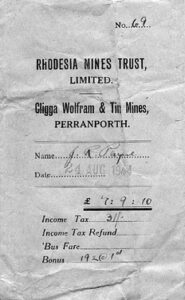

A 1944 payslip from Cligga Mine.

A 1944 payslip from Cligga Mine.

Random notes from the account book:

Cycle first then bus. Cligga started very small 1938, 100 feet deep, men on tribute. Single skip road. Ram at Perrancoombe. Sunk to 200, then 300, three levels holed to cliff. £2.5s.00d per fathom to £5.

Carlos Gribble was the surveyor at Cligga Mine during the Second World War and he seems to have had a healthy sense of humour. It seems that when this well-known gentleman arrived at the gate, he was challenged by Sammy Keast with the customary, “Friend or foe,” to which he answered, “Foe”. The exasperated guard said, “Look Mr Gribble, I’ll ask you again,” only to receive the same answer. Resigned to defeat, Sammy replied, “Oh, come on in then”.

Mining ceased at Cligga at the end of the Second World War and work did not re-commence until 1962 when the West Briton reported:

Start on Cligga Mineshaft

Owners besieged by job-seekers.

Steadily increasing interest is developing in the reopening of Cligga Mine, Perranporth, where shaft sinking to exploit tin and wolfram is expected to begin next Monday…Mr J B Hooper, a member of a famous Cornish mining family, said that they had been inundated with applications…One of the dozen men currently employed is John Gribble, a grandson of the late Captain Gribble, who reopened Cligga Mine in 1937 when it was worked for tin and wolfram…The current preliminary work has been mainly confined to building the necessary surface installations for the second stage of prospecting… the sump is being pumped out and cleared of stone, debris and rubbish. With the cleaning of the sump now nearly complete, the sinking of the first exploratory shaft will begin…the headgear in use is about the only visible sign of the reopening of the mine.

The headgear was prefabricated and erected by Geevor Tin Mines Ltd., it stands 33 feet high and was brought to the site in sections and erected in five hours… The main shaft, Contact Shaft,(4) was deepened and a drive made seawards; this work lasted until 1965.

Cligga is one of the oldest mines in Cornwall, it has been worked on and off for two or three hundred years, and is even said by some to have been mined by the Phoenicians between two and three thousand years ago,

An interview with John Gribble of Chacewater, grandson of Captain Tobias Gribble and another member of St Agnes Silver Band

“I was working for Foraky Ltd, a shaft sinking company, in 1962 and 1963. We started at 300 feet – the old bottom level where the tunnels come out on the beach. We had to cut a twelve feet by six feet exploratory shaft and I worked on it down to the 500 feet level (it eventually extended to 550 feet below surface). There were four men working in that small space, each with his rock drill and air and water supply – it was a bit congested. The usual pattern of work was to clear the rubble from the last blasting until there was a clean base. We than started drilling, first with three feet long bits, then with six feet and finally with nine feet bits. To save time we often missed out the shorter one but the drill was a bit unwieldy and it was difficult to collar the hole. When we’d finished the drilling, the explosives were placed and we’d retire to a safer level or, more probably, leave work and the next shift would clear our muck. Of course, our progress varied with the hardness of the rock encountered.”

The deepened shaft below bottom level

The deepened shaft below bottom level

“I remember one incident when we were lucky to get out alive and if it wasn’t for the skill of the whim driver, it might have been a different story. We were working at about 500 feet and had just filled the kibble – it was being hauled to the surface when it snagged. The ends of the old tunnels – where they met the shaft – had been boarded up and metal guides fixed to make sure the kibble ran smoothly past these points. At the 100 feet level the kibble caught the end of one of these guides and dragged it off pulling away the timber boarding and the build-up of rubble behind. We heard the commotion and immediately pressed our backs to the wall as boulders up to one foot in diameter plummeted down the shaft. One of the chaps fell into the centre of the pit and we managed to pull him back to the relative safety of the perimeter. Luckily for us, the boards jammed against the shaft sides otherwise they would have come down like missiles. The whim driver must have realised what had happened because he immediately stopped with the kibble still in the shaft and still loaded with stone.

Once the dust had cleared we were able to take stock of the situation; we had two men injured and the bell rope had been ripped from the wall – we had no way of communicating with the whim driver.

Suddenly, inch-by-inch, the kibble began to move back down the shaft, threading its way past the displaced timber. John Allen, from Blackwater, was a first-class whim driver who relied less on our signals than his own skill at judging the kibble location from the markings he’d made on the whim wheel and the steel rope. He brought the kibble to within six inches of the shaft bottom and it was only when the four of us had clambered on, and he’d detected that our weight had stretched the rope and taken the kibble to the ground, that he started the slow, upward journey. Once again, with pinpoint accuracy, he stopped at the 300 feet level where we were met by our rescuers who had come in through the adit at beach level. A slight fracture of the skull and a broken leg was the total of our injuries but from then on there were some anxious faces whenever there was an unusual noise from above.”

In 1972, International Tin Services spent some time sampling the mine and later, in 1985, Concord Mines proposed to re-open it but this was discontinued when the tin price suddenly collapsed, making it no longer viable.

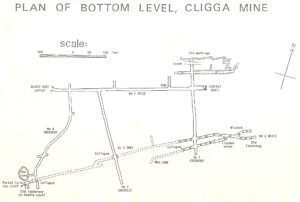

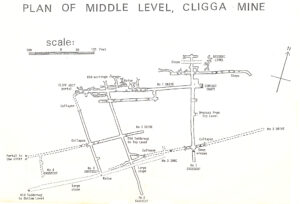

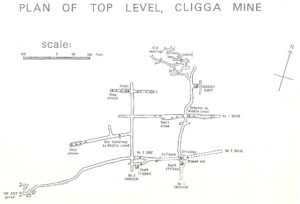

Tony Bennet of Rosevale Mine provided these maps of the three levels at Cligga

That includes this brief chapter in the life of Cligga Mine except to say that in August 2010, four members of Perranporth and St Agnes Probus Club had a guided tour of the workings: an account of their experience can be found here: https://cornishstory.com/2021/11/04/a-trip-to-the-underworld/

Then. ‘twas just us and the ghost…

Into the darkness.

Into the darkness.

A longer ladder would have been handy

A longer ladder would have been handy

Trevor Greenslade in thoughtful mood or just watching his step.

Trevor Greenslade in thoughtful mood or just watching his step.

Our guide – you don’t have to be slim to work here but it helps.

Our guide – you don’t have to be slim to work here but it helps.

A Cousin Jack Chute

A Cousin Jack Chute

Footnotes:

- Old Men’s Workings: Excavations by the mine workers of past centuries.

- Drive: Extending a mining tunnel.

- Grass: Above ground at a mine or Bal.

- Contact Shaft: According to Bruce Grant of Perranporth, Contact Shaft was so named because it was driven on the contact joint between the granite and killas.

References:

Jericho to Cligga by Clive Benney and Tony Mansell (Pub: Trelease Publications ISBN 0-9545583-6-7

Heritage Gateway, a location for information on historic sites and buildings, including images of listed buildings.

H G Dines: Researcher, author and historian on Metalliferous Mining.

Alfred Kenneth Hamilton Jenkin: Cornish historian with a particular interest in Cornish mining and author of The Cornish Miner.

Tony Mansell is the author of several books on aspects of Cornish history. In 2011 he was made a Bardh Kernow (Cornish Bard) for his writing and research, taking the name of Skrifer Istori. He has a wide interest in Cornish history, is a researcher with the Cornish National Music Archive and a sub-editor with Cornish Story.

I was the (slim) guide on that tripand remember the day well.

Curiously, I am working over at King Edward Mine, restoring the very frame that once graced this mine, and later Nangiles and finally Wheal Concord

It was a fascinating experience Roy – thank you. Tony