David Oates takes us right to heart of this small community in the second article in the Kernow’s Smaller Villages series. His memories are evocative and engaging as he paints a vivid picture of life in this Cornish village. You can find the other articles in the series here.

Until leaving home to go to college I lived all my life in a small community close to Camborne and formerly of greater importance than the churchtown itself. Surrounded by the remains of several small mining ventures, some of antiquity, its pedigree is far more illustrious than these suggest and takes us back to the Middle Ages.

That community is set on the stream that forms the western boundary of the old parish of Camborne – it is the village of Barripper, whose very name is unusual. It does not derive, as all other place-names in our area do, from the Cornish language. It is essentially French in origin, in 1397 known as “Beau Repere” – a “beautiful resting place” where good lodgings could be found and in medieval times it far outstripped any other local community in importance, including, in all probability, Camborne .

Why was this now sleepy village so important? The answer appears to lie in the road which runs through it, as Barripper is on the direct route to St Michael’s Mount which in medieval times would have been a monastery. This was a time when power, influence and knowledge lay in the hands of the ecclesiastical authorities and it was to them that the uneducated masses would look for direction. In those terms a monastery like that at St Michael’s Mount would have been of considerable significance and would, in all probability, have become a place of pilgrimage.

There is some evidence to support the possible importance of a route through Barripper, crossing an even older track following the Connor River? The origin of the name of this settlement being so obviously not Celtic, sets it apart but there are other pointers. Until relatively recently the stream at Barripper broadened into a large pool at this point where the water would have been quite shallow and the earliest settlement would have grown up around this fording place. This pool was crossed by stepping stones and the inhabitants of the village were known in West Cornwall as “Barripper Ducks” and the pool itself as “Barripper Harbour”. I have a photo of my mother standing on these stones in a spot far more attractive than the modern location where the water is channelled underground.

However just outside the village the road crosses the stream on a bridge and immediately adjacent to this bridge is a farm called “Penfurzes”. If we trace this name back to medieval times it becomes “Ponsferras”, made up of three elements in Cornish, “pons” meaning a bridge, “for” meaning road and “ras” meaning great. Thus, “the bridge of the great road,” suggesting a routeway of some significance. Apart from appearing to lie on an important route, Barripper itself was of ecclesiastic significance, with a chapel in the area dedicated to “Blessed Marie” and it was the scene of visitations by Bishop Lacy of Exeter in 1427 and his suffragan in 1433. In 1427 he ordained local youths including one Philip Godryvy who had undoubtedly followed an ancient track to Barripper from his home by the sea at Gwithian.

There is, it seems, considerable evidence to support the importance of Barripper in earlier times, lying on a major route

Barripper has had times since the medieval period when it achieved some significance as it played its part in the development of underground mining and in fields around the village can still be seen the spoil tips of a relatively small number of mining ventures from the middle of the nineteenth century. One is particularly worthy of mention and still shows evidence of its existence in the name of a house in Fore Street, Barripper called “Silverbell”, probably a corruption of “Silverbal”. This mine produced silver and was known as West Dolcoath in an obvious attempt to emulate the famous Camborne mine and attract investors. I lived at “Silverbell” until leaving to go to college, in sight of the shaft and waste tips of West Dolcoath, and my cousin, Alan Trevarthen, a mining engineer, extracted a small amount of silver from the waste.

It is likely that many of the houses in Barripper date from that mining period, serving this and other, small to medium mines in the surrounding area. They were not that successful, or major money spinners, when compared to the immensely successful and profitable mines in Camborne and Troon, but the long terrace at New Road, and other shorter ones, are reminiscent of the Victorian period and were clearly functional, in both appearance and design, to house the working class.

Even in my youth, when mains water and drainage arrived, some houses still had only one outside, cold tap and a number were still not connected to any drainage system. In those homes where a water closet had not been a priority, that function was exercised in a little stone and slate hut at the bottom of the garden. Our garden still had the stone hut but we had, too, right by the back door, the luxury of a chain which, when pulled, brought the cleansing power of fresh water. There was not, at least in the beginning, any electric light out there and a candle and a box of matches were essential during the long winter evenings – you didn’t have the same desire to go, though, when snow was on the ground.

Those original toilets, though, were unique, consisting merely of a wooden box, with hole cut in the top, over a deep pit, on which one would sit. Light came from a slit in the door and cleansing was undertaken with sheets of newspaper on a nail behind the door. The waste eventually moved, by gravity, into another pit adjacent to the stone hut and then accumulated until, with addition of kitchen waste, it composted and was used on the garden. Using the euphemistically termed “night soil” for cultivation would doubtless be banned by the Health and Safety people in this day and age but some of those Barripper gardens had vegetables to be proud of. One such garden was maintained by Jimmy Carter, who lived “up top town” as you enter the village. I spent many happy hours playing with his daughter who was sadly to die at an early age. Jim was a farm labourer, working for the Rowe family at Gear Farm near Ramsgate, but he was another of those humble men who found his true vocation in chapel where his faith empowered him to speak with authority.

The village has its more shadowy side as well and at the bottom of the field behind the St Michael’s Mount Inn is one of the darker, more mysterious aspects of Barripper – a small, marshy area, intersected by a stream whose source is a spring in the next field, and surrounded by trees. It has been known to generations of Barripper people as “Cap’n Jacks” and is reputed to be haunted – there have been locals, one of them my grandfather, who profess to have seen the ghost. Tales also exist of a young girl being drowned there but like much else it is lost in the mists of time. There are banks and mounds there which suggest the possibility of a long disappeared dwelling, perhaps the home of the legendary Cap’n Jack, but the truth will never be known. This whole area was extensively explored by the old tin streamers so this place may represent a remnant of that industrial past.

The meadows alongside Cap’n Jacks were a joy, always damp but rich and fruitful. One, to the east, towards Ramsgate, was, in truth, not a meadow but a marsh, in spring and early summer filled with ladies’ smock, meadowsweet, buttercups and mounds of pyramidal orchids. Frogs and toads lived there in abundance but the real joy for me in childhood days was the certainty of finding a newt in every clump of water weed you plunged your hand into. These fascinating and beautiful creatures are similar in appearance to the sun basking lizards found in local hedges but so different in their habits. We would carry them home to keep for a while, then we returned them, or they liberated themselves – I did not discover until much later that part of their life cycle was spent out of water. We would spend the whole day there in the heat of summer, going home only when our bellies dictated.

At the marsh’s centre, and its source, was a spring that gave its name to the present rash of buildings and concrete nearby – and what a sense of mystery it was. Bubbling straight out of the ground, it was crystal clear and icy cold. We would lie flat on the ground beside it and plunge the full length of an arm into its depths, burrowing through small stones and into the clay at its sides. The relative cold made your arm numb and there was always that thought at the back of childish minds that somewhere in those cold depths lived some creature that might lay hold of your arm! Being so near to Cap’n Jack’s, with its air of foreboding, and the knot it tied in your stomach, it was a place where creative imaginations ran riot. Perhaps it wasn’t all imagination. Though, many a time I have been there, engaged in some feat of water engineering such as creating a dam, when I have been acutely conscious of someone watching me, only to turn and find no-one there.

The profusion of colour and the rank, heady scents of the plants in that marsh are no more – it has been drained long since and is now a green desert like many of the other meadows of my youth. One plant does remain, however, for along its fringes grew a type of reed with delicate, thin, spiky leaves and feathery flowers that often had a tinge of red. Bunches of this were always gathered to adorn the sides of the pulpit in chapel at harvest festival and they still endure in the hedges today. Most pulpits have sheaves of corn around them but perhaps in watery Barripper these reeds were more fitting. Those meadows in that damp but luxuriant soil are, sadly now, swallowed under concrete and tarmac of the modern estate of Springfield Park but once fulfilled a more natural and satisfying role as the land around a farmhouse, long since demolished and lived in by the Carlyon’s who were in our family. As one of the extended family once said of Mr Carlyon, who was a mining engineer, “not a Barripper man, but still a decent sort of chap”. Their house was abandoned as a dwelling in my youth and used to store hay but there was a fascination in going there, walking into rooms and upstairs with an undeniable presence of those who had gone before.

One incident stopped me going there when a boy with whom I had been playing some time before went there, playing with matches and set fire to some of the hay. No great damage was done but that was the end of that. It would be a much sought after smallholding today but was swept away when the inevitable bungalows arrived. The meadows were always cut for hay in summer, not the clinically green and sterile swathes of the modern farm but rich conglomerations of grasses, flowers and herbs, all dried white in the heat of the June sun before being gathered in the traditional way and stored for winter use. I have spent many happy hours turning those meadows of hay by hand, with a pitchfork, once, twice a day in the shimmering heat until it was dry enough to be gathered into larger piles to be loaded onto the horse-drawn wagon to be carried home. Big fields would have a number of turners but for me, in these small meadows, it was a solitary activity and an enduring memory of the sun on my back, the glorious scent of the drying grass and the constant sound of running water from the stream that edged the field.

It was one of life’s rich experiences indeed, at the end of the day, to ride back on the top of the swaying, horse-drawn load, enveloped in the scents and sensations of summer. No hard, prickly bales then, but soft piles of loose, dried grass. My particular job in Barripper at hay harvest was to take food to the workers in the field, carrying a huge wicker basket, almost as big as myself, loaded with bread, cold meats, heavy cake and either tea or the superb, locally made “herby” beer, the ingredients gathered from the local hedgerows. Sadly the secret of this nectar is now gone – I know the ingredients but not the quantities, so a taste probably handed down through the centuries has disappeared for ever. In Barripper it was always made by Mrs Harvey, who lived in the Square, near the Institute. She was the grandmother of one of my primary school companions and was the village post-woman. I assume she used her long walks around the farms and cottages of the district to collect the raw materials for that brew. “Herby” was common in many households and all of us knew the sound of a bottle exploding due to over exuberant fermentation and the yeasty smell that betrayed its presence! It was consumed with gusto by teetotal Methodists who, presumably, forgot, or were ignorant of, what happened when sugar and yeast came together in a warm environment!

One story truly illustrates the intimacy and love of that community I lived in: In June 1993 I went to see Ronnie Emery, living at that time in Bognor Regis, who was evacuated from Islington to Barripper during the Second World War. Ronnie and a number of his school friends ended up in this corner of West Cornwall and his memories tell us much of life in a small village in West Cornwall.

Ron spoke of leaving London as an eight year old, not knowing where he was going and of experiencing a seemingly endless journey, coming eventually to Barripper where they were all greeted with great kindness – he remembers Freda Pascoe kissing them all on arrival. Ron lived with my grandparents as one of the family, and says that, without exception, all the folk from Barripper and the surrounding area took these tired, frightened Cockney children to their hearts. He was adamant that he knew of no incident where an evacuee was treated badly by the Cornish folk. He said, in spite of the wartime circumstances, he counted that period at Barripper among the happiest times of his life. He speaks movingly and passionately of my grandfather, of the kindness and love shown to him and felt, as we all did, that he is was much part of the family as any blood relative.

One man in the village had a car and Ron said on Sunday afternoons, after Sunday School, he would take the evacuees to Gwithian. For some this would have been their first experience of the sea – their only knowledge of anything remotely rural being a London park, surrounded by railings and gates. He recalls one little boy of five, Tommy Smith, standing on the edge of the cliff, looking in awe at the grandeur and majesty of the Cornish coast before him – the light-house at Godrevy and the rolling surf. After standing speechless for some time, he turned to the gentleman who had brought him and asked, “What time do they shut the gates, mister?” This simple, intensely moving remark sums up completely the difference between inner city life and the wild freedom of living near the Cornish coast. Willie Pearce also had a lovely cottage garden with a seat in it and one day Tommy was found seated there, under the impression that this, too, was a park. Tommy’smother could not bear to be parted from him and he eventually returned to London to be killed in the blitz. It is somehow comforting to know that for part of his brief life he knew the relative peace and joy of Cornwall in wartime.

Psychologists sometimes say we only remember the sunny days and enjoyable experiences but I truly have no bad memories of living in a rural Cornish community in the years following the Second World War. That village life has now long gone and I shall never see those sunshine days again.

Join us again next month as we explore another village in the Kernow’s Smaller Villages series. You can also follow us on Twitter and Facebook to keep abreast of our upcoming content.

Hi David,

What a wonderful account of life in Barrippar many years ago. It was so enjoyable to read as childhood memories flooded back in my memory. We had 3 generations who lived in the village called Kneebone. There were cousins too at Ramsgate. Dad often spoke about Barrippar Harbour!

What has also interested me is that I noticed you have written a book about Troon so I assume you have great knowledge of the village too.

Granny Kneebone, was know as Millie Hosking before she married and lived at Troon. When mum & dad died I took over the family tree and have discovered an older brother to granny called William Orchard/Hosking who lived in the village but granny had never mentioned him! Granny did tell us about a younger brother who died in a house fire when she was a young child. The family lived in the square and this little boy who was poorly was wrapped in a blanket and left in front of the fire. Their mum Libby went across the road to get some medicene and the little boy decided to poke the fire, the blanket became loose and caught alight. Granny and auntie Bessie were in the room with him, looking after him! It must hae been horrific but I cannot find any info on it! I think it was before uncle Fred was born.Must have been early 1900’s. Gt.Granny Hosking was a seamstress and did most of the villagers needlework repairs.

Hope you didn’t mind me contacting you….

Kathy Corigan

My great grandfather and grandmother William and Ellen Heather lived on the farm by the Barripper village hall. It’s now a dog kennels. My grandfather and his five brothers were born there. My great grandfather William worked in Dolcoath mine and sold vegetables in the market in Hayle. He also played for the cricket team in Barripper just before WWI.

I enjoyed your article very much and the medieval history was very interesting.

Dear David

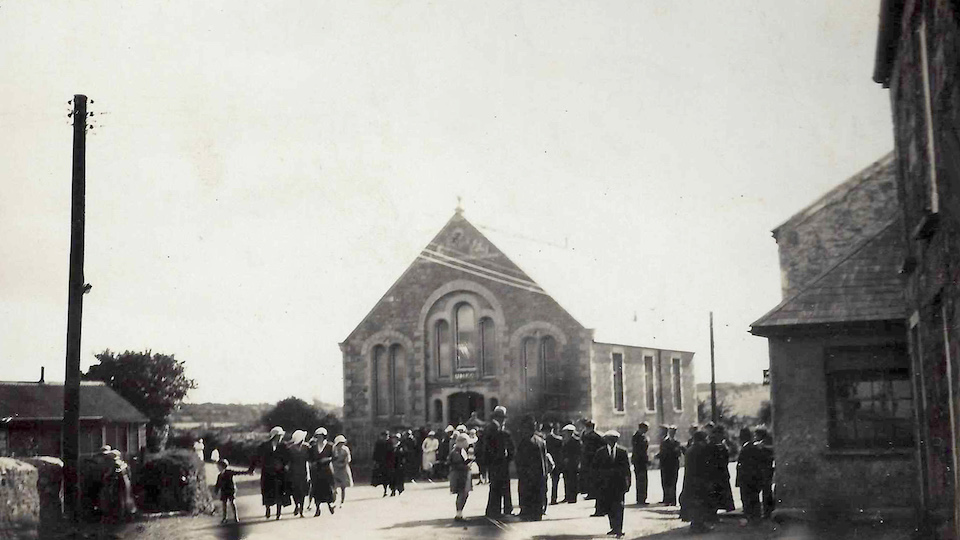

I wonder if you ever met my dad William ‘John’ Pearce who was born in 1930 and lived with my grandparents Elfreda ‘Charlotte’ Pearce and William ‘Jack’ Pearce in Barriper Road. My father’s family lived in Barriper for generations and were all miners. I remember so well going with my grandma to Harvest Festival at the Weslyan Chapel! I enjoyed very much reading your Cornish story.

Hi David, Nick Burt suggested I contact you. Trying to get your book and learn more about walking routes between Gwithian and inland. Hope to hear from you. Thanks! Craig

I found your page fascinating. My 3x great grandfather James Bennetts and his wife Margaret owned a cottage at Barripper Bridge. He was born 1781 and died 1843. The 1841 census simply shows them along with two of their daughters living at Barripper. One of their sons and my 2x great grandfather was Samuel Bennetts who lived with his wife at Ramsgate. The family were involved in copper mining. I have been researching my family for years, but with more time on my hands in the last few months have been reviewing my information. I then came upon your web page – excellent.I would be very interested if you had any information on the Bennetts families of the area.

Hope all is well & best regards – Andy

I live in Chymder opposite The Blue in Helston. I traced the history of our original owners to Richards and eventually got to Halgarrack Farm in 1730ish.I’m pretty sure they had mining interests because one of them married Luscombe of the Bristol Brass Company.I’ve no idea of which mine as yet. But went today to have a look up the lane and you see an old garden wall and archway at the back of the farm.The rest is later but i was amazed by the river at Botetoe.We then followed it up past Pendarves Wood, it became even more violent. Has that river ever been used further upstream by mines? What were the two lakes used for? One in the wood and one at the end of the rubble pathway.There’s a parking spot near the river at Botetoe Bridge that has a wall near the road and the river cuts up to the road. Has that ever been a mill?

How very interesting to read about the village of Barriper. I remember my mum who was born a Tredrea telling me about an uncle who was organist of barripper Chapel and how he died at the organ playing fir his daughters wedding

And now after all these years we are buying a bungalow and coming to barripper to live. Thanks again for sharing your wonderful memories.

I came across the history of Barripper whilst researching my husbands family tree.

His (and my) surname is BARRIPP.

It has always been a topic of discussion whenever someone asks me my last name and all his family have never known where it came from. We always thought it was made up?

His family emigrated from the Ukraine/Little Russia to England in the late 1800’s and settled in London before emigrating to Australia in the early 1900’s.

I wonder why Ukrainian Jews would be passing through this small town? and to have then taken the name on as their own?

Any hints or answers to my deliberation would be wonderful.

Thank you