Port Penzance

A short strategic and operational history

by Professor Neil Hawke LL B, Ph D, FRSA

Beginnings

This is an illustrated strategic and operational history of the port of Penzance as seen through press coverage and other written sources over the years since Penzance was first regarded as a ‘haven’. Penzance received its first charter in 1429, marking its status as a ‘haven’ though borough status occurred only in 1614, again under the terms of a charter. Even earlier though fresh, salted and dried fish was being exported, particularly to France and Spain but it was not until the late 15th century that the port was formally recognised as being open to foreign trade. Much later, and into the early 18th century Defoe published his book, ‘A Tour through the whole of Great Britain’ (London, 1724) where he saw Penzance as a place that boasted good trade and a good many ships belonging to it despite its remoteness. Around the sea-borne trade there developed many businesses such as brokerage, ship repair, shipbuilding, sail making, chandlery and victualling.

Early trades

Early trades at Penzance were dominated by fish, whether fresh, dried or salted often exported. By the 15th century Penzance could boast that something approaching 40% of its overseas trades were involved with fish. At the beginning of the 16th century, in 1512, the borough obtained a grant of anchorage, keelage and bushellage which was conditional on use of the dues extracted being used to keep the quays and ‘bulwarks’ in good repair.

Tin was another important commodity and at various places, such as Penzance, there were quarterly coinages though much tin purchased here was conveyed to Gweek over land, in order to avoid the depredations of French privateers. Such was the importance of Penzance that after 1663 all tin produced west of Camborne had to be assayed and coined at Penzance. In the course of the 17th century there was a marked increase in both home and overseas trade through Penzance. Into the following century and trade continued to increase, necessitating the construction of a new harbour in the 1760s. Mounts Bay was usually full of inbound vessels from all sorts of exotic locations around the world. Against this background the Royal Navy was active in countering the French privateers just referred to. Into the 19th century and something approaching half of the tin extracted locally was being shipped overseas from Penzance. Indeed, on the back of trades such as those in tin, records demonstrate the growth in the number of registered shipowners in the port, some of whom were active in the emigrant trade to places such as North America and Australia. Some of these registered shipowners were also active in running the packet ships which called at Penzance. Many of the shipowners registered at Penzance were the beneficiaries of investment from local people. By 1822 there were 22 registered shipowners in the port. Such was the further growth of shipping through the 19th century that at least a dozen foreign nations maintained vice-consular representation in the port.

Letters of marque

Letters of marque represented a government-issued licence authorising the holder to attack and capture enemy vessels before their presentation before the Admiralty Court for condemnation and re-sale. Penzance was one of many ports in the South West that applied for letters of marque thereby permitting shipowners identified with the port being able to arm their vessels against ‘enemy’ privateers which would typically be armed also. Among Penzance vessels taking advantage of this regime there were particularly successful privateers. Doe, Kennerley and Payton in the Maritime History of Cornwall (University of Exeter Press, 2014) identify a member of the Penzance fleet, the 30 ton Dolphin, which was armed with ten guns and a crew of twenty five: she took nineteen prizes, including nine Dutch vessels seized in 1781 during the Anglo-Dutch wars.

Eighteenth and nineteenth century infrastructure

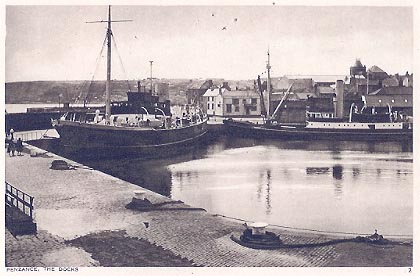

The ancient pier that dominated the port was re-built between 1765 and 1785 and in 1812, fearing competition from Porthleven across Mounts Bay, the pier was lengthened. Three years later, in 1815, a drydock was constructed, further enhancing the port’s commercial potential. In 1845 the shelter provided by the harbour was enhanced with the construction of the Albert Pier and the south pier was constructed eight years later. Into the twentieth century there was criticism of the port’s facility. For example, a borough councillor was reported as saying that ‘…Penzance harbour in some respects is a bye-word among seafaring men as being considerably out of date and ill-equipped to meet the needs of today’. (The Cornishman, January 16, 1930) This was but one example of controversy surrounding port developments both before and after this date, as will be seen. One such controversy concerned the construction of the port’s floating (wet) dock at the end of the 19th century. The Cornish Telegraph of March 23, 1882 reported alarm amongst ratepayers about the considerable overspend on the scheme against a background of the Council being accused of recklessness.

Until the 1960s there is no doubt that Penzance had a long trading history. Some evidence of the port’s strategic importance has been seen already though additional evidence is discussed, below. In his paper ‘Do docks make trade?’ (University of Exeter 1992) Gordon Jackson examines this question in relation to the history of the port of Grimsby and it is a key question where Penzance is concerned. There is no black and white answer to the question whether any port has developed proactively, or reactively; as with Penzance it appears that, depending on available economic and political signals, port development has been built on both variables. Where there has been proactive development of Penzance port it has occurred in anticipation of the perception of economic and political signals. The presence of a political element here arises from the fact that the port of Penzance has been in municipal ownership for much of its history.

The Cornishman newspaper of July 21, 1887 carried a graphic example of the fact that docks do not always make trade and that there are fine lines of judgement to be made, in this case by the local authority owners of the port:

‘A fine grain-laden vessel, one of a class whose presence in the Penzance dock has been such a pecuniary gain to the town (dues about £200, cash spent by vessel, crew etc. from £150 to £200) arrived at Falmouth early this week, safe so far on her voyage from Australia to Penzance. But she will have to wait at Falmouth from eight to ten days in consequence of the water not being deep enough to enter the Penzance dock. This fact caused us to inquire what her destination would have been supposing the dock had been two feet shallower, as was first planned and acted on? The answer was ‘She would not have come to Penzance at all’. We, therefore, easily see that but for the foresight and action of [the Council] such vessels…must have discharged at Falmouth, to the gain of Penny-come-quick and the loss of Penzance.’

Clearly, one driver of decisions affecting port development is the likelihood of competition, in this case from nearby ports such as Falmouth, or Porthleven.

Across the years the assumption must be that the local authority owners of the port were pushing in the right direction, if only from the evidence of ship registration, Penzance being a major registry in the area. Between 1830 and 1855 the registrations recorded at Penzance were as follows:

| Schooners | 136 |

| Barques | 5 |

| Brigs | 17 |

| Brigantines | 8 |

| Cutters | 4 |

| Luggers | 20 |

| Sloops | 37 |

| Smacks | 3 |

| Square riggers | 10 |

| Yawls | 5 |

To put this into a more general context, Dr Helen Doe in the Maritime History of Cornwall has this observation, saying that statistics on ship registration

‘…show that from 1829 to 1870 Cornwall expanded at a rapid rate in terms of sailing ships. In 1829 the number of vessels of more than 50 tons registered in the Cornish ports was 270, with a total tonnage of 22,291. By 1870 there were 535 ships with a total tonnage of 66,770’.

Despite Penzance being the port of registration for Mounts Bay fishing craft, it was only a port of last resort for fishermen, Newlyn being the real centre of the local fishing industry. Nevertheless, considerable numbers of big Plymouth-based trawling smacks made Penzance their base for spring trawling during the 1870s and 1880s. Where exploitation of catches was concerned, from the 1820s effective control of the Cornish pilchard export trade was dominated by two merchant houses, one of which was Bolithos of Penzance. (Pawlyn, The Maritime History of Cornwall).

Into the 20th century there was from 1975 an ill-starred ‘mackerel boom’ which saw the wet dock at Penzance crowded with trawlers from Hull, Peterhead and as far away as Belfast and Barra. (Carter, The Port of Penzance, A History, 1998).

The strategic importance of a port might also be judged by its place in the customs hierarchy. In the case of Penzance, it was a constituency of the so-called headport of Plymouth. As such the port was able to conduct both overseas and coastal trades, as well as having its own customs operation though not always without controversy as when Collectors of Customs were accused of compromising liaisons with known smugglers and others in the community. (Stephens, The Maritime History of Cornwall).

Penzance added to its strategic status in wartime, given its location: for example in both WWI and WWII Mounts Bay was an important convoy collecting point. Even beyond wartime, the Royal Navy used Mounts Bay as a base for Summer exercises undertaken by both the Home and Channel fleets. Many local seamen, with an eye on increasing their income, joined the Royal Naval Reserve, and in wartime were to be found in various seagoing branches of the Royal Navy. Throughout WWI the wet dock at Penzance was crowded with the smaller naval craft while outside convoys gathered within long anti-submarine booms. Nevertheless, WWI took its toll on merchant shipping around Penzance with a trail of sunken vessels strung along Mounts Bay. In WWII naval forces such as patrol boats and minesweepers returned to Penzance. Indeed, the Royal Navy took over the port and dry dock and in the area coastwise shipping was rigidly controlled from July 1940. Most of the German bombing of Penzance was aimed at the port area, up to 1942. Visiting ships, damaged by enemy action or otherwise, posed big problems for the port particularly in relation to lubricants and spare parts. Many spare parts were machined in Holman’s dry dock fitting shops. (Carter, The Port of Penzance, A History, 1998).

Brief reference has been made already to some of the infrastructure developments in the port, generally as a response to trade opportunities. There is no doubt that 19th century development of the port excited considerable controversy, particularly where the building of the wet dock was concerned. The granite-built wet dock, sometimes referred to as the floating dock, was constructed by enclosing the south west corner of the harbour. Part of the dock development also involved the creation of a new, enlarged dry dock which in 1904 came into the ownership of local company Holmans with a separate entrance through the adjacent Ross bridge. The grand opening of the dock was announced when the mayor and corporation walked in procession to the site. The Cornishman newspaper on November 13, 1884 carried a full report of the opening on Monday, November 10th. The newspaper reported that the opening ceremony was attended with the best and truest good wishes of all who strive for the progress of Penzance.

Flags and bunting were in evidence as the mayoral party arrived for the opening. Three steamers, dressed overall, were the Queen of the Bay (a paddle steamer employed on the service from Penzance to the Isles of Scilly), the Trinity House tender Alert, and the Thames, a coaster owned by local shipowner, Bazeleys. The Cornishman went on to report that the ceremony was simple and brief, after which and with a clear sky and warm sun the steamers proceeded towards St Michaels Mount before turning and entering the new dock, cheers greeting them as they entered, after which a bottle of champagne was dashed against the dock wall.

There is no doubt that the new wet dock benefited trade to the port though for a number of years there was simmering discontent among local ratepayers about the cost of the enterprise. Despite acquisition of the wet dock there were often pressures on the port’s infrastructure. One of the best examples is seen in a report in the Cornishman in its edition of December 27, 1922, reporting a campaign to increase storage capacity for china clay in the context of new exporting opportunities to the United States. There was local recognition of the constraints facing the accommodation of capacity for china clay while at the same time addressing port facilities for Coast Lines who were running liner services calling at the port. Another element in the debate was anxiety about the loss of coal imports for the local mines at Botallack and Levant, the issue here being the fact that coal could be imported more cheaply through neighbouring Newlyn.

Reference was made previously to liner services using the port, another factor that certainly enhanced the port’s status. Liner services to Penzance can be traced back to the early 1830s. Noall, in his Book of Hayle, refers to the brig Maria ‘…loading goods and passengers at Broad Quay, Bristol, for Hayle, St Ives [and] Penzance’. Graham Farr in his West Country Passenger Steamers refers to the fact that, in 1831, commercial interests from Penzance, Hayle and Bristol formed the Hayle Steamship Co. in order to operate a weekly packet service from Bristol. Many such packets did not choose to enter port and an exposed quayside, instead preferring to ferry goods and passengers by boat to the quayside. Further into the 19th century Dr Roy Fenton in the Maritime History of Cornwall reports that

‘From 1868 Samuel Hough’s London to Liverpool steamers called at Penzance and their success probably stimulated a major Cornish venture into regular liner trades by George Bazeley…The service prospered and, in 1880, Bazeley extended his services to Bristol [and] opened a Penzance to Liverpool service in 1882…but this was not well patronised and was withdrawn in a matter of months…Other liner companies putting steamers into Penzance…had now been purchased by Coast Lines Ltd…[which] pursued an aggressive policy of acquisition and in 1920 made an offer of £160,000 for Bazeley’s business…and in the Spring of 1920 the business was transferred to Coast Lines…the administration moved to London, whilst Penzance was served by calls from Coast Lines’ steamers on longer routes.’

The Isles of Scilly

Excursion steamers had visited the Isles of Scilly as early as the 1830s. However, as the 19th century progressed it was realised that there was commercial potential in a regular passenger and goods service to the islands and, in 1858 the Scilly Isles Steam Navigation Co was formed, facilitating a regular steam packet service from Penzance. Thirteen years later the West Cornwall Steamship Co was formed by commercial interests in Penzance and thus began what was a complementary service, reflective of demand. The first purpose-built packet to serve the islands was the Lady of the Isles, completed at their Hayle shipyard by Harveys in 1875 and sustaining the service for twenty nine years. As the 1890s approached it was clear that demand was again increasing and the Lady of the Isles was joined by another vessel, the Lyonesse, completed again by Harveys at Hayle in 1889. Later vessels to carry the service were the Scillonian, completed in 1926; Scillonian II completed in 1956, the Queen of the Isles completed in 1965, and Scillonian III completed in 1977. Over the years additional vessels have been taken into ownership or chartered in order to meet demand for cargo space to and from Scilly.

Trinity House

Any reference to port infrastructure at Penzance has to take account of the presence of the Corporation of Trinity House and its local responsibilities for lighthouses, lightships and other navigational aids. Trinity House created a depot in the port in 1861 whereupon plans were put in train for the construction of the Wolf Rock lighthouse which was completed ten years later. On completion of the wet dock Trinity House tenders were very much a fixture, characterised latterly by the steam tender Satellite and, finally, the motor vessel Stella. Ultimately the depot was closed, largely as a result of the automation of local lighthouses and light vessels.

Coal and other trades

Reference has been made already to various trades through the port of Penzance, such as china clay, an example of a trade (unlike coal) which did not sustain over any lengthy period. Indeed, it was coal that dominated over many years, at least until the gas works closed in the 1960s. However, the bigger picture shows that coastwise trade around the United Kingdom started to decline quite significantly from the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. That decline continued in the interwar years and continued immediately post war. What is striking about Penzance is that almost all the coastwise shipping was discharging cargo, at least since the demise of china clay exports up to about 1930. In Coastwise Shipping and Small Ports (Ford and Bound, 1951) the authors set out the situation in Penzance in 1948 with the following statistics:

| Tonnage | |

| Coal | 28,383 |

| Cement | 800 |

| Feedstuffs | 1,512 |

| Other merchantise | 603 |

| Total | 31,298 |

One issue which the authors refer to in this immediate postwar world was the lack of storage or adequate handling equipment in smaller ports. The need for more and better storage facilities was certainly in evidence at Penzance in the 1920s and may well have contributed to the decision by Coast Lines to reduce and finally phase out their liner services calling at the port. Reference will be made below to stevedoring and cargo handling since it was a matter of great moment to shipowners and charterers that vessels are efficiently dealt with in port, whether loading or discharging. In the case of Penzance the concerns were obviously dominated by the speed with which discharge could be accomplished. The shipping accounts of J H Bennetts, who imported most of the coal, show that coal in particular was handled in various ways, not least through coasters with their own discharge facility. The company’s shipping accounts archived at the Cornwall Record Office (AD731/5) provide an interesting cross section of vessels arriving to discharge cargoes, principally coal: set out here is a selection running from 1948 through to 1954:

| Vessel, nationality and date | Cargo | Quantity (tons or otherwise) | Method and period of discharge |

| Eldorita (British) March 1948 | Coal | 228 tons | Grab crane to lorries (8 hours) |

| Marie Schwinge (German) July 1948 | Timber | 125 standards | By ship’s gear to lorries (23 hours) |

| David M (British) August 1948 | Coal | 124 tons | By ship’s gear and buckets to lorries (11 hours) |

| Quo Vadis (Dutch) October 1948 | Potash | 324 tons | By ship’s gear to lorries (20 hours) |

| Nellie (Dutch) November 1948 | Potash | 187 tons | By ship’s gear to lorries (16.5 hours) |

| Hullgate (British) March 1949 | Coal | 161 tons | By ship’s gear and buckets to lorries (13 hours) |

| Aridity (British) September 1949 | Coal | 325 tons | Grab crane to lorries (11.5 hours) |

| Antiquity (British) September 1950 | Coal | 292 tons | Grab crane to lorries (8 hours) |

| Jim M (British) December 1950 | Coal | 400 | By ship’s gear and buckets to lorries (13 hours) |

| Wea (Dutch) April 1951 | Coal | 220 | By ship’s gear and buckets to lorries (8 hours) |

| Cranborne (British) August 1953 | Coal | 360 | Grab crane to lorries (9 hours) |

| Result (British) March 1954 | Coal | 153 | Grab crane to lorries (5 hours) |

Towards the end of the 1950s and into the early 1960s the trend was in favour of larger colliers. One such example was the steam collier Londonbrook whose deadweight was over 1200 tons thus allowing much greater loads to be delivered.

The stevedoring necessary in any port has rarely been a simple process, particularly in the smaller ports of the United Kingdom. Regulation of dock work became an important political issue as the 20th century unfolded. In his article The National Dock Labour Scheme in Cornwall (Cornish Studies, 2004, University of Exeter Press), Terry Chapman relates how, at the start of the 20th century there were no trade union members among the dockers of Penzance, and that it was not unknown for cargoes to be diverted to the port as a result. Chapman goes on to say that in the 1930s there were 90 Penzance dockers in a voluntary registration scheme. Such schemes, it has been suggested, enabled dock employers to avoid any undue interference with settled, conscientious working arrangements that might face interruption with an influx of dockers displaced from elsewhere. The Second World War saw a decline in the number of registered dockers and Chapman reports just 59 at Penzance in 1941. Beyond the second World War the decline in coastal shipping already referred to necessitated a certain flexibility among employers, as a result of which dockers tended to be transferred between ports according to where the work was at any one time. The National Dock Labour Scheme was introduced in 1947 and endured to 1989. Chapman reports that the number of registered dockers in Cornwall between 1952 and 1957 remained stable at about 250 though the number fell to 200 during the following five years. Into the 21stcentury and there is no need for dockers in a declining port like Penzance.

Penzance shipowners

As the 20th century dawned it was clear that the sailing coasters that frequented Penzance were in decline. Indeed, those sailing coasters that continued to trade to Penzance were usually powered by auxiliary engines. Increasingly at this time the important coal trade to the port was dominated by the steam colliers of James Henry Bennetts who learned the coal trade in South Wales before establishing a business at Penzance in 1882. At the turn of the century J H Bennetts was supplying coal far and wide within West Cornwall.

George Bazeley was referred to previously, in connection with liner trades to Penzance. Bazeley was a prominent merchant and businessman in and around Penzance as well as at Cardiff. Bazeley formed the Little Western Steamship Co and it was one member of the fleet – the Thames – that had the honour of first steaming into the new wet dock on its opening in 1884. Ultimately Bazeley’s company was taken over by Coast Lines in 1920, as was described previously.

Port Penzance: a success?

In well over seven hundred years, Penzance has reacted with considerable success to the evolving shape of maritime trade, being in part the beneficiary of its location. The fact of the port’s remoteness through many years before road transport started to impact on sea-borne traffic gave it considerable advantages as well as attracting investment in the local economy. Ultimately one of the most significant factors in the port’s decline was the reducing reliance on coal. Though the wet dock still functions for a variety of purposes, none of them represent the trades that previously characterised the port with the exception of the passenger and goods service to the Isles of Scilly. The other feature of the port that has endured is the dry dock, still after many years in the ownership of Holmans. One final point should be made about ownership of the port which has been in the public ownership of the local authority for many years. An issue worthy of further study is whether the port’s fortunes might have been at all different had the facility been in private ownership.

Sources

- J H Bennetts, Shipping Accounts (Cornwall Record Office, AD731/5)

- Carter, The Port of Penzance, A History (Black Dwarf Publications, 1998)

- Chapman, The National Dock Labour Scheme (in Cornish Studies, 2004)(University of Exeter Press, 2004)

- Defoe, A Tour through the whole of Great Britain (London, 1724)

- Farr, West Country Passenger Steamers (T Stephenson Ltd. 1967)

- Ford and Bound, Coastwise Shipping and Small Ports (Blackwell, 1951)

- Jackson, Do Ports make Trade? (University of Exeter, research in Maritime History, No.2, 1992)

- Noall, The Book of Hayle (Barracuda Books, 1998)

- Payton, Kennerley and Doe (eds.), The Maritime History of Cornwall (University of Exeter Press, 2014)

- The Cornishman newspaper

- The Cornish Telegraph newspaper

Photographic credits

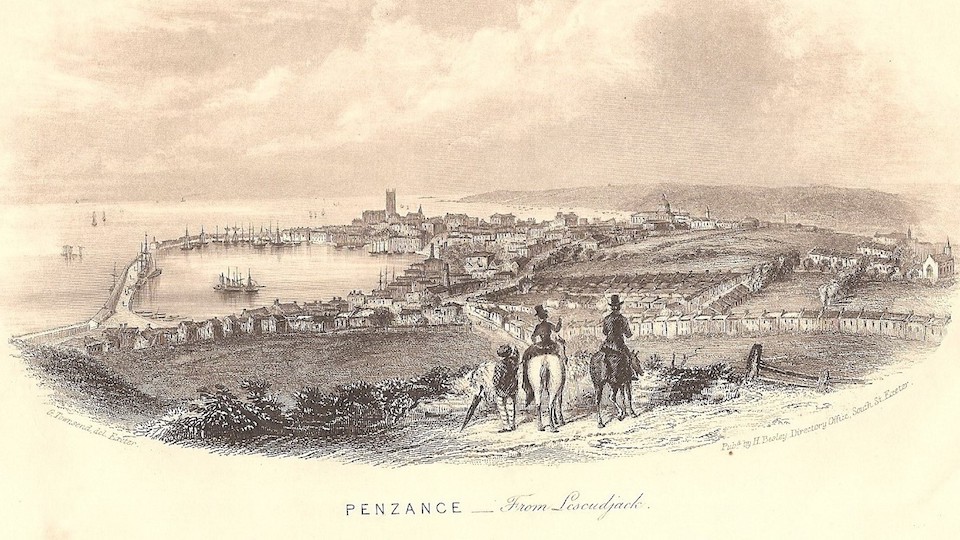

- Title Image – View of old Penzance [Author’s collection]

- Image 1 – The auxiliary schooner William Ashburner being towed out of the wet dock having discharged a cement cargo [Morrab Library Photo Archive]

- Image 2 – THV Stella at Penzance, berthed alongside the wet dock [Author’s collection]

- Image 3 – Trinity House vessels Patricia and Satellite berthed in the wet dock [Author’s collection]

- Image 4 – Wolf Rock Lighthouse relief from Penzance, showing Trinity House motor boat from THV Satellite off the landing [Author’s collection]

- Image 5 – Bishop Rock Lighthouse relief from Penzance, showing THV Satellite approaching (Author’s collection]

- Image 6 – The coaster Adaptity alongside the wet dock [Author’s collection]

Very interesting . My dad William Carter ( Bill ) use to work for TH .

Reason we live in PZ .

Quite interested in local history . Found the bit about how dry dock came about. Thank you . Pete.

Dear Neil,

Thanks for your most interesting paper. I have recently been working on the employment of lighthouse keepers for there were many in local situations such as Penzance, Mevagissey, St Ives etc, who were not employed by Trinity house. I believe the local authorities at Penzance (for example) were responsible for the harbour lighthouses and employed these man who lived locally. We have names from censuses, but we need more information as to their employment.I wonder if you have any specific references to this? Thanks

Dr Ken Trethewey http://www.pharology.eu ; http://www.lighthousekeepers.co.uk

Hello, I worked on a small Shell? tanker in Holmans in 1965 or 66, while serving an apprenceship with Vickers Armstrong in Newcastle. It was a refit and we worked on the steering gear. I’m trying to find the vessel name and dates it was in Penzance, hope you can help.

My Great great grandfather George Tremeer, diver and mason, might of contributed to harbour building projects in Penzance. Records show he was living in Daniel Place Penzance in 1884 when he married Mary Elizabeth Hosking, resident of the Quay and daughter of John Hosking, Engineer. He was still in Penzance during the 1891 Census. The family were still living there in the 1901 Census and up to 1909. Probably known as a Diver. He helped build the North Sea Canal on Submarine Contracts with Henry Lee and Sons. If early photographic evidence exists of him at work or documentation that would be amazing!