A biographical memoir on author Lamorna Spry’s grandfather and his sister on the fishing riots between Newlyn fishermen and fishermen from East Anglia in 1896.

This story is about William Osborne Guy, known to the family as Willie Guy, but whose nickname as a child was ‘Clue’ – nobody could ever tell me why. He was born in Newlyn just outside of Penzance in the far west of Cornwall on August 5th in 1887.

His family had fished in Newlyn for generations. By all accounts he was quite a lad, often getting into brawls. One story was that when he’d heard the policeman was coming to speak to his mother he laid a trip wire across the road, thereby getting into even more trouble.

In those days Newlyn was an extremely poor fishing community.

It was also very religious and staunchly Methodist with strict adherence to the Sabbath. When William was only 9 years old, trouble was brewing in Newlyn. The fishing boats were small family owned drifters but they were having to compete with much larger company owned boats from the East Coast, mainly Lowestoft and Yarmouth.

Being ‘Sabbath Keepers’, the local fishermen refused to fish on a Sunday, but the owners of the East Coast boats had no such scruples and would sell their catches on the Monday to the buyers from Billingsgate for the highest prices.

When the Newlyn fishermen tried to sell their catches on the Tuesday, the prices dropped dramatically. Prices could fluctuate enormously, and newspaper reports of the time show that in early April 1896 prices of 18 shillings for 120 mackerel were recorded.

However, days before the riot, they were fetching a mere 3 shillings. Finally on 18th May a number of Lowestoft boats, already in the harbour, were boarded by local fishermen and their mackerel catch was thrown overboard. Reports at the time refer to over 100,000 mackerel being lost, although this may have been exaggerated.

Many local people gathered to watch the affray from Newlyn’s North Pier. When the remaining Lowestoft boats arrived to discharge their fish, three boats anchored in the bay were boarded by men in gigs, who overwhelmed the crews.

With about 30 to 40 heavily laden East Country boats stranded in the bay, the harbour master, William Strick, rowed out to attempt to allay further trouble and persuade the Lowestoft boats not to try to enter the harbour.

At Newlyn, the fishermen fixed a heavy chain across the entrance to the harbour to prevent boats from entering or leaving. At Mousehole and Porthleven the ‘baulks’, heavy wooden structures normally used to protect the harbour from storms, were put down to enforce a boycott of both harbours and prevent any more boats from landing fish.

Eventually, their actions prompted a stern reaction from the government of Lord Salisbury that sent in dozens of extra police, three gunboats and 330 redcoats of the Second Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment.

One Member of Parliament even asked if the Government should introduce a ‘Measure for Cornwall’ on the lines of the Irish Coercion Bill.

Unfortunately, there is only negligible photographic evidence of the rioting because the reporter that was on the scene had his camera thrown in the sea. As a result of the rioting nothing changed and the East Country boats continued their Sunday fishing.

But for 10 years afterwards, gunboats continued to patrol the waters off Mounts Bay during the mackerel fishing season.

Willie’s sister, Eliza Jane, was 16 when the riots took place and this is her account of the riots, recorded when she was 90 years old:

“Well that will have been in ’96. I think the riot was […] years ago. We used to have a big fleet of Lowestoft boats catch the mackerel and they were a very rough lot of men, a very rough lot of men, drinking when they were ashore, always public houses and drinking – a dirty lot of men.

Well it’s true – we wouldn’t go out at night if the boats were in for the world. We wouldn’t go down long. Well anyhow our fishermen were a good living lot of men and they honoured the Sabbath.

Well now it come on so bad that these men used to go to sea Friday nights and Saturday night and Sunday when ours never used to go. Monday mornings they would bring their fish to market and they would have the best price for all their fish. When our men would go the Monday by Tuesday morning and they couldn’t sell them, sometimes had to throw them away – but we couldn’t get a living, our men.

My husband was a fisherman; we couldn’t get a living. The first winter we were married my husband got 8 shillings all the winter – a good job as I had a few pounds by me. Well now our men come to think, ‘well we shall have to do something – we can’t go on like this – we shall have to call a meeting.’ So my dear life they called a meeting.

The Porthleven men, the St Ives men and the Mousehole men all met together up Paul and said, ‘Well we shall have to do something to drive these men from going to sea on the Saturday and Sunday’.

Well now, come a week or two and in the end our men went to board the Lowestoft boats as they were coming in the harbour, so our men went aboard their boats and some of them took the fish and threw them all away.

The Lowestoft men used to bring packers with the buyers who used to buy the fish – Cushway and Wren and all those big buyers from Billingsgate.

The packers didn’t like that and they interfered with our men. It became so bad that in the end the harbour master William Strick went out to stop the fleet from coming because if he didn’t there would have been bloodshed because now they had started to fight.

You see, now the Penzance people came over because back then we and Penzance never agreed – the footballers can never agree. Newlyn and Penzance were always falling out and fighting.

Well now the Penzance people started to come over and made things worse and in the end we had to have the soldiers down from Plymouth. It went on all day like that – you know – fighting and then policemen were being insulted and lots of people were arrested.

‘Well now,’ my father said, ‘you’re not to go on the pier, mind.’

This was in the early morning. But Susie and I went. It was a terrible job and all night soldiers were there and everyone was up in arms.

At 1 o’clock we’d gone to bed and at last we heard some shouting and screeching: ‘ how can ‘ee go to bed ! how can ‘ee go to bed ! how don’ ‘ee come down women and everybody. Bring if you haven’t got nothing to protect ‘ee bring your shovel and your poker with ‘ee’.’

The next day soldiers came and the day after that it went quiet but it didn’t make much difference. The year before that we had the flood with water coming down the Coombe washing everything away. Where the water came from nobody knew.

There were a lot of arrests because now the men began to thump the policemen and a good many got arrested – one man was sent to prison for 6 months. He was the ringleader – Gib Triggs, he was called. When he came home we had the Paul band out for’un. I can see him coming over the bridge now.

So that was the riots in 96.”

There were three brothers and five sisters in the family and with failing family fortunes all three brothers decided to leave Cornwall to take their chances in the New World.

It’s important to consider the enormity of this when you think that none of them had probably ever strayed east of Penzance, let alone Cornwall or the UK.

But by 1911, Cornish emigration had been commonplace for over half a century so they probably felt some comfort in the knowledge that they would be meeting their fellow Cousin Jacks. Relatives and friends would no doubt have stirred their imagination for America and its opportunities.

On July 13th the Cornishman newspaper reported that Willie had travelled with a friend, James Richards – such was the importance of the event that it commanded a newspaper article.

Back at home, the fishing industry in Newlyn continued to decline and their family fishing boat, the Pride of the Sea, was ignominiously broken up in 1914. (As an aside, it’s wonderful to see the resurgence of Newlyn’s fishing industry today).

So Willie starts his memoirs:

“I will just start and write about my trip to America, which I had heard so much about, and the different places I have been and worked. I left home on 6th July 1911 and arrived at Liverpool on 7th July 1911, leaving there again on the steamship Lake Manitoba which belonged to the Canadian Pacific lines.”

On 15th August 1910, the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette reported that it was this same steamship which returned the infamous Dr Crippen and Miss Le Neve from Quebec back to England, escorted by Inspector Dew and Sergeant Mitchell.

This was the first time someone had been caught through the use of the wireless telegram. Yet another coincidence, because in the 1901 census at the age of 13, Willie was a telegram messenger.

“We called in at Belfast and took on some passengers there. Before I go any further, my passage money was 25/- from Penzance to Liverpool and from Liverpool to Quebec £6. I had a nice voyage across the Atlantic and we was only delayed for a few hours of fog off the coast of Belle Isle which was the first land that we had sighted. We saw several icebergs on the way and one which looked as big as St Michael’s Mount.”

“Of course just one year later in July 1912, the Titanic was to hit one of the icebergs with devastating consequences. And in 1913, the Lake Manitoba itself was involved in a drama when it struck rocks at Orleane Island but managed to reach Quebec safely.”

“Now we passed several islands and one was a very large one – its name was Anticosti Isle. It was getting dark by now and then we turned in and in the morning of July 17th we found ourselves going up the St Lawrence River. It was a very nice sight; the banks of the river on each side with big trees down to the water’s edge.”

“After a few hours we arrived in Quebec and waited there a few hours for the train to take us to Vancouver, the train fare being £8-10-3. A funny thing happened while we were waiting. A fellow was handing out Players Cigarettes to each of us as we passed him. I took my case with me and went around a building and had another packet. I told my friend to do the same but it did not come off.”

“Now we had to buy our own eatables and cook them on the train, the coaches being different than what they are at home.”

“Now this was a long ride on a train from July 17th until the 22nd and we passed through the Canadian Rockies after passing the prairies which is dreaded by all travellers in wintertime owing to the snow slides and we saw several glaciers on the way. The train stopped at a place called Golden.”

“We wanted bread so I went to get some at a shop 40 yds away. While I was in the shop the train bell started to ring. I bolted without paying for it but I missed the train and when I turned round, the Chinese man from the shop was chasing me with a big knife, so I went back and paid him.”

“Now the Rockies is a nice sight. We had two engines and four coaches and sometimes you went through the same mountain twice. Sometimes if you are travelling there is mountain on one side and a deep valley on the other and, at one place called Glacier, the glacier is nearly touching the rail track and it never melts for there is no sun shine on it.”

“Well we got through all well, for we arrived in Vancouver on July 22nd, although my pal James Richards arrived a long time before me on account of me missing the train. We waited there for a few hours and then we took a boat called Charmer for Nanaimo on Vancouver Isle belonging to the Canadian Pacific.”

“So that makes my travelling on two boats and one railroad of the same company.”

“The run was on a few hours and we were too late to get the train for Cameron Lake and had to wait three days for it (it only runs three days a week and while we were there we met a Penzance man, the first we met since we left home). We left Nanaimo for Cameron Lake and we thought we could go all the way by train but we could not, for we had to take a stage coach and ride about another six hours.”

This part of Willie’s memories is quite interesting. He was travelling through an area known as Cathedral Grove containing massive forests and populated by indigenous Canadians. He was actually riding on one of the last stage coaches and, shortly after his journey, the stage coach was replaced by trains. But the railway gave the logging industry access to “big timber” and spurred the demise of the forests.

Not only did he ride on one of the last stage coaches but Willie would have been one of the last people to see Cathedral Grove as it was before the logging. His account continues:

“We arrived at Cameron Lake in the evening of July 25th being 19 days altogether on our journey and the fare all the way costing us about £17-7-0. When I got there I was surprised to see the place, for there were only a few houses and not any roads and I thought I was up against it. I did work a day and a half for a fellow and he paid me at the rate of $3 a day.”

“One day when I was thinking what to do outside a hotel a man came and asked if I knew of anybody that wanted a job, so I said I did and he asked me if could ‘back picket’ for a survey party and I said, ‘You are talking to the very man that can’.”

“So he said, ‘Go get your blankets and be there in an hour or so.’ ”

“Now I did not have any blankets so I told my landlady and I asked her where could I get them and she said that she had some that she could sell, so I bought one and tied it up as if I were a trapper or a prospector. Some clothes I left there in a rig and we rode in the back for about 40 miles.”

“The country was a wild one for it has never been walked on before with white people. Now I know that I had to sleep in tents so I made my bed the same as the other fellows. You drove down four stakes in the ground, the distance between them being the length and the width of a single bed in a house and then you lay long poles from head to foot and had poles that would bend to give it a little spring and cover them with dry leaves. The first night I could not sleep for in the evening I saw a snake outside of the tent.”

“I turned out in the morning to go to work. It was August 5th on my birthday and my pay was $45 and board. I found out that one blanket was not enough so I asked if anybody was going in to Alberni and they said yes, for it was not safe for one man to go by himself for I did not have a gun and there were a lot of cougars about. You could hear them sometimes in the night.”

“Well we walked into town and we did not see anything but we heard the yelling of some wolves but they were in front of us somewhere. We got on all right and stayed the night and walked out the next day with my clothes and blanket to where our camp was. We stayed there for about two weeks and then moved on to another place, getting closer to the township.”

“As it happened, it was on the edge of the river and in the night you could hear the salmon going up the stream jumping out of the water. We had lots to eat. It was the best living I ever had and we had lots of fresh salmon.”

“Here the Indians had canoes and they were fishing for them and then would come up alongside us and sell some of them to us for a couple of empty bottles or an old shirt. It was getting cold now and after a while we were called to Victoria, our headquarters, and we packed up and waited four days for the boat, which was called the Jess, built in England but since lost.”

“We stayed in a hotel, all expenses paid, and when we got to Victoria we learned that we were going out on another job for the 17th on a building for $2.75 a day. I was three weeks at that job and then I went to pull down some houses for the same fellow and had two Italians working for me and I was paid $3 a day.”

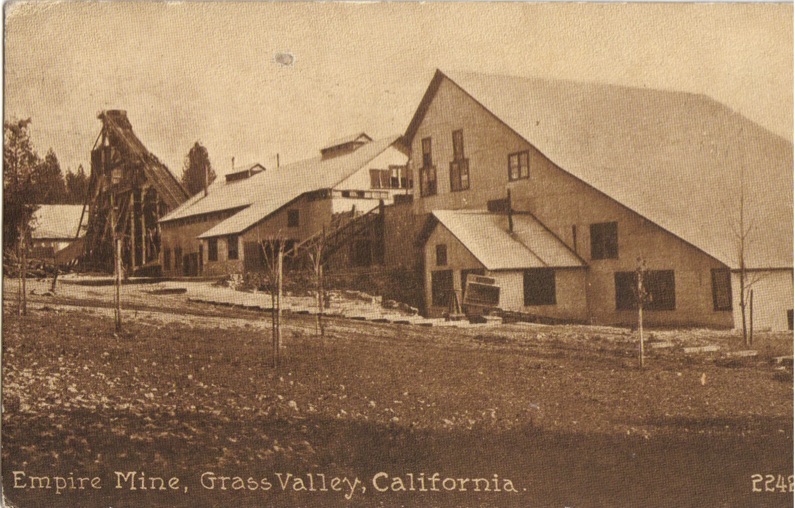

“Now that job got through in a short while and I made up my mind to go to Grass Valley California. On October 21st I left Victoria for Seattle, Washington on the boat Iroquois and from there I took the Southern Pacific Railroad and arrived in Grass Valley on October 23rd. The fare from Victoria to Grass Valley was $29 60c.”

“Now it’s nothing there but mines and I waited two weeks before I could get a job, but I got a job in the Empire Mine at $2.50.”

In the early 1900s, Empire Mine was in its hey days. Stamp mills thundered 24 hours a day. You could set your watch by its haunting whistle that reminded local residents all systems were go at the prosperous Empire Mine. Open for business from 1850 until its closing in 1956, Empire Mine produced 5.8 million ounces of gold. Miners from Cornwall, Wales – and all over the world – left their homes to be part of the action.

Mining is and was a dangerous occupation and the Grass Valley gold mines were no exception with local Cornish newspapers regularly reporting deaths.

In 1913, the Cornishman reported that Mr James Trembath, whilst working in the Argonaut mine, died when the ground caved in and broke his back. They got him back to the surface but he died shortly afterwards.

The sense of Cornishness was intense in places like Grass Valley and the Cornishman newspaper reported in January 1912 that ‘standing room was at a premium last night at the Congregational Church. The Grass Valley carol choir was the drawing card. People of all denominations filled the sacred edifice to hear the old-time carols sung and they were not disappointed. The concert the choir gave was worth going miles to hear.’

The Grass Valley Cornish Carol Choir still exists and has been known to still perform the Carols by Candlelight. Even now, visitors to the Empire Mine museum can order a Cornish pasty.

In 1917 Willie received his World War 1 draft papers for the US army but later returned to the US to work for Ford cars in Detroit, but on a visit back to Cornwall in 1921 he met my grandmother at Penzance fair and never ventured back.