My name is Sue Ward, and I grew up in Melbourne Australia with what I would later learn was a Cornish surname, Tonkin. I was approaching my 40th birthday when I asked my father about our heritage. His reply was vague and trailed off into silence when I realised that ‘Definitely a little bit Scottish – perhaps with some Irish or English thrown into the mix’ meaning that he had no idea. Thus, began a seven-year journey of painstaking (and expensive) research that surprised and amazed me. Dad’s assumptions were correct, and I discovered correlations between habits such as language or family recipes and Cornwall. For example, it was no coincidence that my Irish grandmother (who was taught to cook by her Cornish mother-in-law) baked Cornish pasties that were exactly like the ones I found in Cornwall – nothing like the ‘pasties’ found across the rest of Britain. Another seven years passed while I spent my spare time learning about our place of origin, Cornish culture and history. The following five years have been spent compiling our stories because I knew I wouldn’t be the only one in my family who was interested. Our heritage is filled with amazing people, places and facts.

Last year I visited Cornwall and met up with my friend, a local guide and Cornish historian, Barry West. He took my daughter and I to Nanjulian and I was filled with an incredulous sense of taking what I had of my ancestors’ genes home for a little visit after a 171-year absence. That realisation overwhelmed me, and I sat crying for a few minutes before managing to step out of the car. We walked forward to where I would see everything that I had researched laid out in front of me. The nearby Methodist chapel on the hill that once catered to 200 worshippers (which was later converted to a cow shed and is now a home); Boscregan farm, where my g-g-grandfather’s grandparents lived; Nanjulian’s big house and the much smaller ‘three tenement row houses’ where my g-g-grandfather was raised. A beautiful fresh stream of water ran alongside the house and track, which was dotted with bluebell flowers, nodding gently in the breeze. Following the track and accompanied by the stream, we walked down the Nanquidno Valley, with visible ancient mine openings, like small cave entrances dug into the side of the hill. Lower down the valley, a small wooden plank served as a footbridge to cross the creek and continue down to the beautiful beach. When William left Nanjulian he journeyed for many months before arriving in Australia. I’d done the return trip spending 23 hours on a plane and then 6 hours on a train. Here I was – and I felt instantly at home.

The following is a much-shortened excerpt from my completed Cornish chapter. Hopefully I manage to convey the strength of one entire generation of my family who fled unemployment in Cornwall during the mining slump of the 1850s. The five brothers each sailed ahead of their wives and children to get settled. Their wives and children then boarded for their journey, which lasted from six to sixteen weeks, depending on the strength of wind in the ship’s sails. They relied on their wits, intellect and a solid belief that they could succeed if they stuck together. This notion of family remains strong in my family today. I hope you enjoy the story of my Cornish great-great grandfather, William Tonkin, from St Just in Penwith.

Sue Ward, 2023

Sue Ward, 2023

Cornwall

William Tonkin was born in 1827, and his destiny was vastly different to the fixed lifestyle of previous generations of Cornish miners in south-west Cornwall. His parents were a tin miner named Thomas Tonkin and his wife Margaret Hattam, and they lived in a humble row of three small tenement dwellings made of granite at a remote settlement named Nanjulian, in the Nanquidno Valley. Naturally, William Tonkin would have anticipated his life taking the same trajectory as his father’s, grandfathers’ – and almost all the local men. However, this was a century of social and economic change to the Cornish mining industry. Cornwall had held a monopoly in tin mining, but new discoveries forced the prices down. Wages reduced, mines closed, and people faced starvation in a land that held no alternatives for the bulk of the population. William’s generation was forced away from the homeland they loved in search of work and William died in 1895, over 10,500 miles away from the Nanquidno Valley, in the small mining city of Bendigo, in Australia.

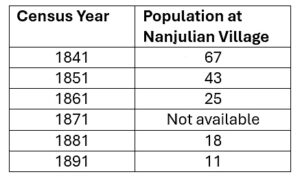

Upon checking the Census, I found the population at Nanjulian had reduced significantly between 1841 and 1891, as shown in the table, below.

Table 1. Population at Nanjulian at each Census

By 1851, Nanjulian’s consistently thriving population of 67 people had almost halved to 43 and 19 of those were the Tonkin family.

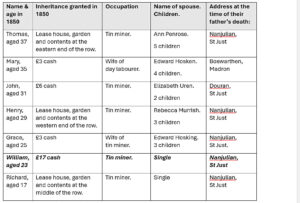

After the death of their parents in 1849 and 1850, William (aged 23) and his siblings (aged 17 to 37) sat down to consider their options. The main inheritance from their father was what remained of his lease on the row of three tenement dwellings for three of his sons and small amounts of cash for the others (See Table 1). Interestingly, William received the largest amount of cash, £17, possibly because their father knew he would be the one sailing away to scout a new life. Table 2 shows the distribution of their father’s only assets to all his children:

Table 2. Distribution of Thomas Tonkin’s assets, according to his last will and testament

(Note: £1 in 1850 is now (2024) equivalent to about £140)

One very interesting aspect of the above, is that 8 adults and 15 children were squashed into the row of three small tenement dwellings.

Nanjulian tenement of three row houses with modern lean-to extension in view. A freshwater stream runs alongside, flowing down the valley and out to sea.

Nanjulian tenement of three row houses with modern lean-to extension in view. A freshwater stream runs alongside, flowing down the valley and out to sea.

As world leaders in hard rock mining, Cornishmen had an open invitation to relocate to South Africa for employment in the newly discovered copper mines, earning above the living wage. Another option was to sail to Australia, as Immigration agents had been travelling from parish to parish over the previous few years, spruiking the benefits of living in a fledgling country the size of Europe. Their third option was the United States, where the Californian gold rush had created a boom in global immigration over the past three years.

New York

Unmarried and without dependents, William was the obvious choice to sail to New York and scout their prospects with mining representatives. In mid-1853, he boarded a clipper ship bound for New York, landing within three weeks. His first letter arrived months after leaving Portsmouth, advising that he had spent six weeks in America, visiting the U.S. immigration office, land agents and mine representatives to get a full understanding of the opportunities for himself, his brothers and their young families. Regular, long-term employment looked promising but there was a down-side to California – the Wild West that wouldn’t suit young God-fearing families like theirs. Land had only been taken from the native Indians three years earlier, there were few women and lawlessness, and danger seemed to be everywhere.

Australia

William sailed for Australia, where a fresh gold rush, much like the one in California, had begun the year before, in 1852, and people from all over the world had been scrambling to get there. Most ships were filled with those escaping the poverty of the Irish and Scottish potato famine, the fall of mining in Cornwall or the Scottish land clearances. Australia had plenty of mining and other work available for the Tonkin family. The convict ships hadn’t delivered new convicts to the east coast for over ten years and labourers were so scarce that farmers faced losing unharvested crops. Desperate, farm labour positions were being offered in return for accommodation plus three times the pay of English shepherds. William was on a mission to see whether this place was suitable to accommodate and sustain himself and Richard as single men, his married brothers, their wives and all their young children.

Aboard the Tarolinta with 119 other paying passengers, William might have felt apprehension and excitement. First, Captain Griffin made way to Rio Janeiro for supplies before continuing on to Melbourne, Australia. This route had an advantage of prevailing winds and sea currents, cutting a four-month trip down to two. The sooner a ship returned, the sooner she could set off on her next trip, so efficiency earned the shipping company big dollars. However, on William’s trip, the winds died down and, without a breeze in her sails, the Tarolinta sat still in a timewarp that caused huge delays to the trip. They arrived at Port Melbourne on 23 October 1853, slowing the eight-week journey to four and a half months (134 days) out of New York.

Steerage Class aboard the Tarolinta was as cramped as Nanjulian. Men were separated from women and children, and everybody slept below deck in a large open space. With no privacy, people with different personal, cultural and religious views tried to get along. Boredom invented new activities whenever the ship stilled, waiting for a breeze to fill her sails. Many passengers wrote letters, ready to post when they arrived in Melbourne. Some would have had George Phillips’ new booklet, ‘The Immigrant’s Guide to Australia’, which went into great detail about Australian gold licensing laws, climate, terrain and what to expect when they arrive. Passengers wrote diaries and letters about the cool, blue water that beckoned some passengers to go down a rope and swim in the sea – though the swimmer was quickly hauled back up onto the deck when a shark was spotted and everyone set about trying to catch the giant fish. Once caught, the dead shark was suspended by its tail, bleeding into the sea before being hauled onto the deck where huge fillets were cut off and carted to the kitchen. Curious men investigated the large organs and distributed sharp teeth among them as souvenirs before the remains were pushed back into the sea.

Some reported the sights at sea as unimaginable. Fields of sparkling stars sat suspended in the black sky and every phase of the moon lit up the water. Dull thuds on the side of the ship during the night brought forth fears of hungry sea monsters and relief swelled across the passengers when the true cause became clear in the daylight. Flying fish had launched themselves from the water, extending and fanning out their unusually long, wing-like gills to glide through the air alongside the boat, dipping in and out of the sea and sometimes crashing into the side of the Tarolinta with a thud. In other waters, dolphins darted left and right alongside the ship, propelling themselves upwards and leaping free of the water as if to have a closer look up at the passengers who stood looking down at them. Huge gulls came to rest on the deck of the ship and the men easily caught the exhausted birds so that they could dine on something besides salted mutton. The monotony, boredom and frustration of living in such close quarters to strangers with different living habits and varying degrees of intolerance and temperaments was enough to prepare anybody for the rigours of their new life in Australia.

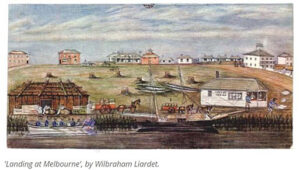

Arrival at Melbourne, 23 October 1853

When the Tarolinta finally sailed into Melbourne, Port Philip Bay was busy with ships waiting their turn to berth and disembark. Eager to get off the ship, some passengers paid a pound to a man in a rowboat and were taken ashore at Liardet’s Beach. William and his new friends finally took their first steps on land after 4 months at sea; following the crew’s advice not to stride but to take small steps ‘lest the ground rolls underfoot and tips them onto their ears’.

Landing at Melbourne by Wilbraham Liardet, courtesy of Museum Of Lost Things (museumoflost.com/liardets-beach/).

Landing at Melbourne by Wilbraham Liardet, courtesy of Museum Of Lost Things (museumoflost.com/liardets-beach/).

Finally ashore, William would have walked along a narrow bush track that led passengers away from the dock, through scrubby ground (low, dry bushes) where large mosquitoes were on the attack. They passed a few roughly built wooden houses along their way towards the township of Sandridge, and thirty minutes farther on was the township of Melbourne.

Melbourne had been founded just 18 years earlier in a tricky and misunderstood treaty between John Batman and eight aboriginal Wurundjeri chiefs of the area. Batman reported that he had signed a treaty with the Wurundjeri that bought a tract of land in return for an annual fee of blankets, knives, tomahawks, scissors, looking-glasses, flour, handkerchiefs and shirts. Nowadays, it is argued that the Wurundjeri people believed they were granting the white folk permission to travel through their land because land ownership and the legalities surrounding private property was not a concept Aboriginal people had ever known. They saw themselves as caretakers of the land and each tribe had a region to which they belonged.

The gold rush inundated Melbourne Town and there were no vacancies in the few boarding houses. Rows of large, square tents stood like a canvas-town and, as October was the middle of springtime, the ground was an ankle-deep mess of mud.

William would have purchased a current map to the goldfields and some other easily carried provisions from a mix of business dwellings in a community of Irish, Scottish, American and Chinese men (there were few women). As anticipated, the lack of a manufacturing industry meant all supplies had been imported along with the immigrants. The shops were very different to those in Cornwall, with luxury and frivolous items bought by gold miners spending their newfound wealth on whatever took their fancy as they drank and spent to excess. Coming from more conservative circumstances, William would have assured himself that he wouldn’t be so wasteful with his riches.

The Goldfields

Mt Alexander was 80 miles north of Melbourne; about the same distance as walking from home at St Just in Penwith to Plymouth. The first leg of the journey was to get through Melbourne, which was an easy three mile walk to Flemington. The track to Mt Alexander was crowded with men carrying heavy packs and tools; most walking together in small groups and others preferring their own company. The line parted to make way for approaching carts and dray, and people dropped off the march to sit in clearings off to the side of the track when they needed rest.

Those travelling in a cart and dray found the track to be so bumpy that they were more comfortable walking and followed the cart and their belongings on foot. William’s few belongings made the trip no more difficult than a walk home from the tin mine after an eight-hour shift. After being confined on the ship, many men found walking a good distance to be a pleasure, though the sides of the track were littered with discarded belongings, too burdensome to carry.

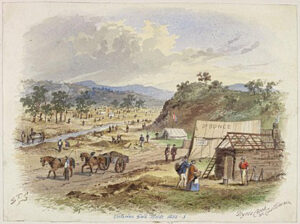

The newcomers enjoyed the unusual landscape. They passed great eucalypt forests of old growth eucalypts, housing familiar birds such as wagtails; also, unfamiliar flocks of unusually big, white squawking cockatoos or the large kingfishers, which let out a surprising human-like laugh. The aboriginal people called the laughing birds akkaburra or googooburra and they came to be called kookaburra by Europeans. The kookaburra’s laugh was contagious, and people up ahead were heard mimicking the bird, encouraging them to make their call again. Sedentary koalas slept in trees all day, and then went on sleeping throughout the night, keeping William awake with their hammer-like snoring. Between each area of forest were great grassy plains where kangaroos grazed during the mornings and slept under shady trees in the afternoons. Prickly echidnas picked ants with their long, thin tongue; and solid, dog-sized wombats lumbered slowly, grazing on roots and grasses. The eucalypt forest released a fresh, clean scent when the sunshine warmed the leaves. Crushing a leaf brought out the same scent, though much stronger and, like so many others, William would have wondered how to convey all this natural beauty in a letter. William had been at school during his teenage years, so was competent in literacy. At the end of their four-day walk, the men could hear the Fryers Creek settlement at the foot of Mt Alexander, which sounded close, but proved to be another few miles. They eventually rounded a corner to see a bustling little city of tents and huts along a river and many hundreds of people working the ground for gold.

Fryers Creek in 1852-3 by S.T. Gill. (1818-1880). Courtesy of State Library of Victoria.

Fryers Creek in 1852-3 by S.T. Gill. (1818-1880). Courtesy of State Library of Victoria.

William and his travelling companions stood atop of the rise, taking in their surroundings. The land looked so untamed in Australia that he might have wondered if this was how the entire world appeared at the beginning of all creation. Nearby, a poster nailed to a tree stated that the Port Phillip Gold Mining Company offered thirty shillings per day for men to come and work in their underground mines. This might have reassured newcomers that, if all else failed, the Port Phillip Gold Mining Company would be a good back up plan. William stepped forward to enter the Fryers Creek gold fields.

At the government mining office, they each produced evidence that identified them as emigrants, not runaway seamen or absent from indentured service. They each paid £1/ 30s for a month’s licence and were advised that if they were ever caught mining or in the possession of gold without the licence, the gold would be confiscated, and they would be imprisoned. The licence bought them 15 feet frontage to either side of a river or main creek, 20 feet of a riverbed, 60 feet of a ravine or watercourse or 20 square feet of tableland or river flats. An additional fee of 30s per month was paid for permission to pitch a tent.

The river’s edge was already crowded with men either sifting watery river soil through a wooden cradle or crouched down, panning. William and his friends were directed to an area in Fryer’s Creek known as Little Cornwall, where the Cornish had gathered to mine together as neighbours. They shared a way of speaking, eating, singing and getting along; and almost all the Cornishmen at Fryer’s Creek had worked in tin or copper mines at home. They relished having control over their own claim, working hours and conditions. Everything William mined belonged to him, which must have felt liberating and powerful.

William encouraged his four brothers to join him, and the following table shows the family’s journeys to Australia in order of arrival:

William received a letter stating that his youngest brother, Richard, was boarding the Shalimar in Liverpool, and was anticipated to arrive in Melbourne mid-February. The letter would have arrived with barely enough time for William to get his affairs in order and make his way to Melbourne before the Shalimar docked.

Melbourne was larger than he recalled, just 18 months earlier. The constant influx of immigrants sustained a demand for accommodation and nineteen boarding houses within a square mile meant there was now an oversupply of accommodation. William planned to stay at The Great Western Hotel’s boarding rooms at 82 Queen Street because it was leased by Cornishmen John Stephens and a Cornishman from Carnyorth (a mile north of St Just) Richard Trezise. The dining room and accommodation was managed by Richard’s sister, Charlotte Trezise. Like William, they came to Australia after their parents passed away.

The Argus newspaper reported that the Shalimar had been seen entering Port Philip Bay late on the afternoon of February 8th. William would have been out of bed and on his way early next morning. The Shalimar was expected to dock mid-morning, but most of the day passed before she was spotted because a small boat had rowed out to her from Geelong to exchange a bag of outgoing mail for incoming mail and a doctor boarded to give passengers and crew a health check.

Richard staggered ashore under the burden of his sack of belongings and William would have beamed at the delight of seeing his little brother and probably walked double step to shorten the distance between them. Upon meeting he would have reached his hands forward eagerly to shake Richard’s hand and take his luggage, but Richard had been weakened by a bout of dysentery, and almost collapsed into William’s outstretched arms. They boarded a coach to The Great Western Hotel, where they stayed with the Trezise’s. Pain and dysentery had deteriorated all aspects of Richard’s health, and he slipped into a very deep sleep before passing away quietly on Sunday 6th May 1855, three months after arriving. Richard was buried at the Melbourne Cemetery, where William later arranged for the memorial headstone to read,

Sacred to the memory of Richard Tonkin

Late of Cornwall, England

Died 6 May 1855, 22 years.

On 31 July 1855, William Tonkin and Charlotte Trezise took their marriage vows at St James Cathedral Anglican church in Melbourne, in the presence of Charlotte’s brother, Richard Trezise and her friend Elizabeth Stephens. St James Cathedral had been built only 16 years earlier and had replaced their ship’s bell with proper church bells in 1853, the year William arrived. Charlotte was an industrious and literate woman and they headed to the goldfields where they rented a house, named Petherbridge. William leased a spot by the Fryer’s Creek River, and they rented out rooms in their house to newcomers and established miners living in tents. William and Charlotte’s home was also met with welcome relief for William’s brothers and their young families after disembarking from the long journey to Australia.

William and Charlotte went on to have 11 children.

William (1856-1939) Married Bessie Shepherd, 1881

Margaret (1857-1946) Married John Dunstan, 1881

Richard (1858-1860)

Charlotte Trezise (1860-1932) Married Charles Welch, 1880

Richard (1863-1863)

Jane (1864-1950) Married John Berryman

Elizabeth (1865-1955) Married Henry Welch, 1888

Mary Ellen (1867-1874)

Emily Grace (1867-1869)

Thomas Henry (1870-1922)

John Trezise (1872-1952) Married Julia Carrigan, 1901.

William died on 7 June 1895 of stomach cancer. He passed away at home in Eaglehawk, which is not far from Fryer’s Creek; and Charlotte died in 1910. William’s last will and testament showed that he owned two homes, all the furnishings and had £125 in savings. After William passed, his sons sold everything and left the Goldfields, which was now suffering from an unemployment crisis. They used their inheritance to fund a move to Perth in Western Australia, 17,000 miles away from Fryer’s Creek. It’s as if history was repeating itself.

References:

- Ticonderoga, the ship of death and disease http://www.phillips.ptwo.id.au/ui%20Ticonderoga.htm and also book by Michael Veitch.

- Description of Melbourne / Sandridge when passengers went ashore Early Melbourne and Victoria By William Westgarth at: https://books.google.com.au/books?id=f9ZRDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=Liardet%27s+public+house+1852&source=bl&ots=sv5BMQ1vpp&sig=ACfU3U2epkF-p-wKmShGQ8b4Iffxde8_Ug&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj1yeXt7LDpAhXeyzgGHRDpCJgQ6AEwB3oECAwQAQ#v=onepage&q=Liardet&f=false

- Stories of emigrant experiences aboard ships https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/shipboard-19th-century-emigrant-experience/journals

- Map of goldfields, 1850 http://www3.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-68/latrobe-68-013.jpg

Hello Sue –

I found you story of your great great grandfather, William Tonkin, fascinating especially as many of the details are similar to those of my great*3 Uncle, William Wall 1819-1907. William, born in Truro, Cornwall, was not a miner, but a stone mason.

In 1852, departing from Plymouth on the Time and Truth, he and his wife Louisa Jane (nee Thomas), emigrated to Australia (unassisted passengers) with their 4 very young children arriving in Geelong, Victoria on 5th Jan 1853. During the passage, Louisa gave birth to another child, a son Benjamin. I can’t think of what it must have been like giving birth at sea on a small ship!

Two more children were born in Geelong.

Many of the descendants of William Wall still live in Geelong. I have been in touch with them in the past.

Susan Coney

Hi Sue. I’m writing to you from Chile, South America. I’ve been surfing the web for many years, looking for information about my ancestors, and I found your story very interesting. Coincidentally, my name is William Tonkin. I was born in Chile in 1966, and my grandfather came from Ireland to work in the mines in the north of my country. He was in Antofagasta in the 1930s. His name was Henry Christopher Tonkin. His son, my father, was born in Chile and was named William Tonkin, like me. I know my grandfather was born in Ballyheigue, but I don’t know if there are any other descendants. Tonkin is a very uncommon surname in my country. I look forward to hearing from you. Best regards.

Beautiful. Many thanks for sharing. So interesting to see that America’s Wild West was not for William.

Hi Sue – Loved the story. My folks were also from St. Just, and have a similar story, also ending up on the Bendigo goldfields. In fact, we are quite distant cousins, so your story helped fill some gaps in my family tree.

I have some updates to your immigration table if you are interested.

Kind regards, Lorraine

Hi Lorraine, I apologise for not responding earlier, I’ve only just seen your message. I don’t know how we could get in contact privately without putting our email address on here for the world to see.

Hi Sue – Just checked again today and saw your reply. Below are some notes I made at the time regarding your immigration table. If you want to contact me separately, go to my family tree website https://www.our-history.net/

On the home page there is a Contact Us option to message me.

Cheers, Lorraine

***********************************

Immigration Table

In 1856, it was Thomas’s eldest son Thomas who came with him to Victoria, not William. And the name of the ship was “Sultana” not “Suttana”. Son Thomas is shown as aged 11 in the passenger list, whereas he would have been 17 at the time – perhaps there was some transcription error somewhere along the way, 17 being transcribed as 11?

Son William came later in 1858 with his mother and other siblings. He is recorded on a different page in the ship’s passenger list – being 15 years old, he is recorded with the single men, rather than as part of the family group. The youngest child Amelia, while not in your table, is recorded with the family group in the passenger list.

The Thomas Tonkin who came on the “Redan” in 1863 is probably no relation. Note that in the Redan ship’s passenger list his occupation is recorded as “wheelwright”. A Thomas Tonkin appears in the 1861 England Census in the Cornish town of Redruth, shown as being born in Redruth in about 1839 and an occupation of “journeyman carpenter” – this is most probably him.

Thank you Lorraine. I had also wondered about why Thomas was shown as 11 years old (instead of 17). Though 7 can often be written to look like 1. I’ll chase up your link and send you a message, hopefully before Christmas. Life gets a bit wild at this time of year. Merry Christmas!

Well this is strange. I’m a Tonkin.. and my grandads father William Tonkin and his father Tommy Tonkin who I have a photo of. Please contact me and I’ll check out if it’s the same family.

Mine lived in Cornwall, Tregony/ St Clements/ Truro St. austell.

Hi Donna, thank you for your comments. I don’t think ours are the same Tonkins because mine were definitely from St Just In Penwith, The names are the same, which might suggest they are cousins who use the same family names. It would be amazing if we were cousins.

My friend is a Tonkin, and her family and are in the family line that goes back to the original the Thomas Tonkin MP of Helston who wrote the original Natural History of Cornwall in its widest sense. The manuscripts are at Kreson Kernow Library, the Courtney Library, Truro Museum, Truro and the British Museum and Library. Before Thomas Tonkin the Tonkin’s line goes back to a marriage with a Welsh family in Glamorgan.

There is a Tonkin Manor at Lambriggan near Perranwell near Perranporth, our present Cornish Grand Bard of the Gorseth is living there and it has the Tonkin heraldry over the front door represented by an Eagle. There is a converted Barn where you can stay called Tonkin Cottage.The present owners are very interested in local history and nature, they have a website.

The main Manor was at Trevaunance Cove, St. Agnes.and three generations of the family lost a fortune trying to build and maintain a harbour for the mining trade, eventually they gave up and it was washed into the sea. Although you can still see the foundations today.

Thomas Tonkin died at a small Manor at Gorran Churchtown where his is buried.Today the gardens that he loved and house are a small hotel.

Most of the Cornish Tonkin’s come from that family. My friends side ended up in Falmouth and St.Just in Roseland until recently.

We stayed at the St. Just YHA hostel about the same time as you were there to watch the Cornish Choughs! There is a Scholar writing about the Tonkin Family who lives in Truro and on some islands in the Pacific.who would know more. Angela Broome Librarian at the Courtney Library until she died a couple of years ago was going to to hold curatorial workshops to republish the Tonkin Manuscripts after I contacted her. Unfortunately with the cutbacks at the Museum there has been nobody to replace her although Archaeologist Jack Nowajowski is in charge on Wednesdays at the Courtney Library. I can forward you emails or contacts.

My Friends father wrote down the main family Tree of the family, I will check down the surname branches. Philip

Hello Philip, Your detailed comment has surprised me, how wonderful! I’ve read Thomas Tonkin MP’s Natural History of Cornwall and never once imagined my Tonkins might be related to him. I’ll read through your comment with a fine tooth comb when I get home, (I’m away for a few nights, we’ve had a crackin’ good start to summer here in Australia). How lovely of you to take the time, thank you very much!

Hi Sue I’m related to the Tonkin family… William Henry Tonkin born may 5 th 1833 newlyn in Cornwall England.. He had a son called William John Tonkin who was born January 14 1871 st column major Cornwall he married Elizabeth annie Glamorgan Wales then they had a daughter called (Elizabeth Jane Tonkin 1900 -1975 ).. who is my gran my dad’s mum

I am related from the surname -(cocking) – Tonkin family on my dad’s side my relatives worked in the mines in Cornwall

I’m a tonkin, and I taped my family back to the 1600s and William is also my grandfather. Assuming my research is correct.

Dear Sue,

Thank you for this valuable information. I was married to Anzabeth Tonkin, daughter of Johann Heinrich Tonkin, from Standerton, South Africa.

Anzabeth and I lived in Cairns, Australia for her last three years of her life. She died of cancer at the age of 51 (12 Dec 1971 – 2 Dec 2023).

She was a world class City and Regional Planner, and a great lover of all people.

She was very proud if her amazing heritage. She definitely knew about her Scottish connections, as she still had a tartan pin that belonged to her ancestors.