Oh, ye who never knew the joys, try it! Remember Redruth Market, there you can have all in perfection and in no town in the kingdom is there greater abundance or quality…

~ a London gentleman, 1778

…the absurd notion which is held by the illiterate…

~ Cornish Telegraph, 21 October 1857, p2

…he…has offered me for sale a hundred times…

~ Rebecca Hodge, qtd. in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, 15 April 1820, p3

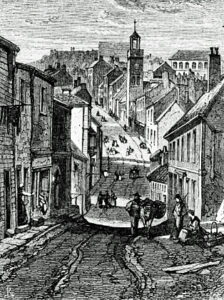

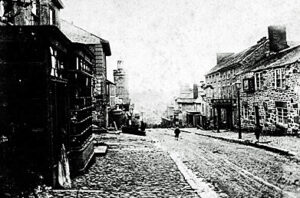

A sketch of Fore Street, Redruth, by J M W Turner, 1811. The lean-to roofs of the old market are just visible on the left below the clock[1]

A sketch of Fore Street, Redruth, by J M W Turner, 1811. The lean-to roofs of the old market are just visible on the left below the clock[1]

In May 2017 a Community Interest Company, Redruth Revival, purchased the old Buttermarket on Station Hill, which in years past had been the kind of place you never ventured in after dark. Redruth Revival’s vision was that the Buttermarket would eventually

become a focus for community use and offer an innovation business centre to offer vibrant communal office space to new and existing businesses, with a particular eye on young entrepreneurs leaving college or university[2].

This rebirth, or reimagination, of Redruth as a vibrant market/business town, has gone from strength to strength. In 2020 Redruth Revival won an Historic England grant worth £4 million to renovate the Buttermarket, which is now a Grade 2 Listed Building, on account of its architectural and historical interest[3].

In November 2024 the Buttermarket reopened, as a food hall, shopping hub, and courtyard to accommodate local bands[4]. The Buttermarket’s own website claims it’s “Redruth’s coolest comeback”, a place

…for the best up-and-coming culinary talents to showcase their work in the heart of Redruth…Forget stuffy establishments, the Buttermarket is a laid-back playground for foodies and culture vultures alike. Think kaleidoscopic street food pop-ups and funky artisan stalls, all buzzing with the energy of passionate locals doing what they love…[5]

October 2024. By the author

October 2024. By the author

In promoting the market they have recreated, Redruth Revival’s webpage carries the quote from a London gentleman with which I opened my essay:

Oh, ye who never knew the joys, try it! Remember Redruth Market, there you can have all in perfection and in no town in the kingdom is there greater abundance or quality…[6]

Though this was written back in 1778, their use of these lines shows how the Revival think-tank want to create the illusion of historical continuity. Their Redruth Market, is similar to, if not better than, the market of 1778, which is a point worth discussing.

From the 1330s, when Edward III granted a charter permitting it, to the 1950s, there was a weekly market in Redruth[7]. Taking the period of late Georgian England, which is when the London gentleman extolled the market’s virtues, to early Victorian England (this essay’s timeframe), Redruth Market certainly rivals the modern-day incarnation for variety and abundance. And this in the days before railways, when everything in Cornwall was transported by horse and cart, or, in the case of livestock, simply driven to market. In 1810 for example, you could buy Copper Ore by auction[8]. Or vegetables, from Penzance, in 1841[9]. In 1847 a man from Gwithian harvested an entire field of oats, and sold them off at 10s a bushel[10]. There was a tithe sale in 1834[11], cattle of many breeds in 1844[12], or butter and dairy goods on offer in 1849[13].

The Buttermarket, Redruth, c1870. First built in 1825-6 for Sir Francis Bassett. Note the wooden railway viaduct. By kind permission Kresen Kernow, corn02860

The Buttermarket, Redruth, c1870. First built in 1825-6 for Sir Francis Bassett. Note the wooden railway viaduct. By kind permission Kresen Kernow, corn02860

As the examples above hope to demonstrate, clearly the Redruth Market of the early 1800s was very different to the one of today. Back then, the town was obviously an established rural trading centre, attracting business from all over West Cornwall: not only tradespeople and farmers from Penzance or Gwithian, but from Truro[14], Breage[15], Falmouth[16], Mawnan Smith[17], or St Keverne[18]. The population increase during the period of the Industrial Revolution, coupled with the rapid rise of urbanisation, created greater demand for agricultural foodstuffs and textiles in town centres, which the people of the Cornish countryside sought to profit from[19]. In short, supply went to where the demand was.

The modern Redruth Market deals in the expensive, the organic, the luxury: yes, the bread from the artisan bakery stall probably tastes better, but it’s cheaper in the supermarket down the road. Contrastingly, in 1848 a woman in her 70s had to walk from Illogan to the market, just to buy meat[1]. Redruth Market’s focus is no longer agricultural or industrial trade, but to bring money, investment, and business to the town. Where once it was mainly the concern of the labouring classes, its feel is now distinctly middle class.

The appearance of the market has altered too. For a start, The Buttermarket was only built in 1825-6; until 1795, the market was held in a wooden building on Fore Street until that was demolished as an obstruction to traffic, the market being rebuilt slightly further down the road in 1801[2]. Every week pigs, cattle, sheep and poultry would have been driven through the streets, along with carts crammed with goods being pulled by horses. Towns in this period of urban explosion struggled to cope with the increase in traffic (and manure), and the traditional capacities of many market areas became inadequate. This resulted in many injuries to pedestrians, increased challenges to regulation, noise, antisocial behaviour, and unpleasant sights and smells: in many market towns cattle were slaughtered and skinned on the spot, to the disgust of the more well-to-do attendees[3]. Needless to say, this is not an issue in the Redruth Market of 2024.

Engraving of West End and Fore Street, Redruth, c1850. Kresen Kernow, ref. AD3039/6

Engraving of West End and Fore Street, Redruth, c1850. Kresen Kernow, ref. AD3039/6

There was also an increase in crime and sharp practice. In 1824 a Wendron man was indicted for buying pork at the market, and reselling it on the same day, for an inflated price[1]. In 1822 men from Camborne were fined for having “defective weights” and “false beams” on their scales[1]. In 1839 a butcher stole and killed a bullock, carrying it to the market for sale[1]. Shoes, stolen, were also on sale in 1839[2]. This is clearly not the Redruth Market encapsulated in the quote from 1778 that Redruth Revival would like to be recalled, or indeed be associated with. One way or another, you could attempt to buy or sell anything in the Redruth Market of the late Georgian era, both over the counter and under it.

You could even buy a wife:

On Friday last a man led his wife, by a straw band which was fastened round her neck, into the market at Redruth, and put her up to auction. This exhibition, the first of the kind at Redruth, drew together a crowd; but very few appeared disposed to become purchasers. After a considerable time, the sum of two shillings and six pence was offered, and the woman was delivered to the purchaser…[1]

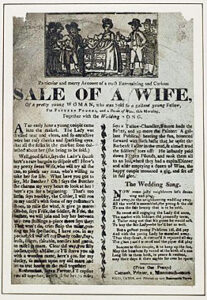

A wife sale at Smithfield Market in 1797[1]

A wife sale at Smithfield Market in 1797[1]

From being a scarcely believable folk memory[2], there have been many fine studies of the historical phenomenon of wife sales in this country in recent years[3]. Considering Cornwall, Elizabeth Dale has surveyed all the alleged occurrences of this practice (apart from this one[4]), but there has yet to be an in-depth case study of a genuine Cornish wife sale, such as the one that happened in Redruth Market, on Friday December 10, 1819. Who were the people involved? How did it happen? And, the question that everybody asks me when I read them the brief initial report from the West Briton given above, why did it happen?

From the newspaper reports of their hearing[5], you can sketch an outline of the protagonists’ lives. On June 1, 1798, William Hodge, a bachelor, married Rebecca Small, spinster, in the Church of St Mary Magdalene, Woolwich, by banns. John Busby was the church official, and Richard Lingard and E. Edwards were the witnesses. Hodge and Small both said they were of the same parish, Hodge signing the register with a mark, Small signing hers with a flourish[6]. Where they were born, how long they had lived in Woolwich (if at all), and where they went immediately after their wedding is a mystery.

At some point, the relationship went sour. At the hearing, Rebecca Hodge stated she had not lived with her husband for “the last ten years”[7]. William Hodge drifted to Cornwall, with Rebecca following – or maybe it was the other way round. She said she had seen Hodge during this time, but “was never alone with him, he having repeatedly threatened to take away my life”[8]. Perhaps they both originally came from Cornwall, had moved to London and, when the marriage began to fail, returned to more familiar faces and places. But we can only speculate. It does seem certain though that William Hodge fell on hard times, and was of a violent disposition. In 1816 he was imprisoned for six months for “disturbing and assaulting the paupers in the workhouse at Wendron”[9]. In 1817, now crippled, Hodge was imprisoned and fined for stabbing a man at Marazion workhouse[10]. Less than two years later, and somehow making his way as a labourer in Stithians, he was sentenced to three months in Bodmin Gaol for petty theft[11]. Hodge was a man on the very margins of society, disabled, violent, and probably desperate, one of the 100,000 paupers in England and Wales during this period, housed in 1,900 workhouses[12]. One can only imagine what his life was like.

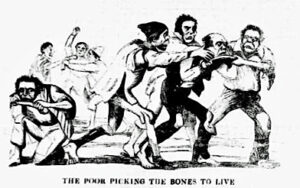

Workhouse inmates fighting over bones meant to be used for fertiliser, 1845[13]

Workhouse inmates fighting over bones meant to be used for fertiliser, 1845[13]

Rebecca Hodge found work in Penryn, binding shoes in the company of a man called William Andrew. Andrew was the man who ultimately purchased her from Hodge for two shillings and sixpence[14]. In August 1822, Andrew and Rebecca were married in the parish of St Gluvias, by banns, she again being the only member of the union to be able to sign her name, though this time she is listed as a widower[15]. In September 1821 William Hodge died and was buried in Stithians workhouse, leaving his estranged wife free to legitimately marry. Hodge’s age at death is given (roughly) as 40, making him around 17 at the time of his marriage in 1798. As we shall see later, this is significant[16]. Rebecca, sadly, did not have long to enjoy her new marriage, being buried in St Gluvias parish in November 1822. She was 46, making her around 22 in 1798[17]. Andrew remarried, dying in 1831, aged 56[18]. As biographies go, these are painfully short. In fact, the details that remain of their lives fill less space than the column inches devoted to their activities in Redruth Market in December 1819.

A Parish Officer of the early 1800s[19]

A Parish Officer of the early 1800s[19]

William Trevorrow (or Trevorra, or Trevorrah, accounts differ) was a busy man. Apart from being an innkeeper in Redruth[20], he was also the town’s Parish Officer, Redruth’s figure of law enforcement in the days before a regular police force. The job was unpaid, part-time, and burdensome. He had to try and prevent crime, lock up various felons and hoodlums, was permitted the authority to read The Riot Act if required and, under the Vagabonds and Vagrants Act of 1494, had the power to clap undesirables in the town stocks. He also had to monitor trading standards, keep a watchful eye on local taverns, restrain loose animals (and this would have proved challenging in the days when livestock roamed the streets), attend inquests, and collect parish rates[21]. Trevorrow was certainly kept occupied by Redruth’s populace. In 1822 some barley flour was alleged to have been stolen from him[22], and he had to give public notice of his authority to convey prisoners to gaol[23]. Throughout the 1830s he was involved in hearings in various ways[24].

Maybe Trevorrow as Parish Officer was an officious zealot, or he utterly loathed the onerous – and unpaid – duties of his office. Or he even supplemented his income unofficially by being in the pay of several shady locals. Whatever the truth, he was on duty in Redruth Market on Friday, December 10, 1819. We’re not sure if this was out of choice, or whether his superiors had warned him to keep his eyes open in what was increasingly becoming a trouble spot. The marketplace must have swelled with the influx of humanity from West Cornwall. There would have been a body swell of tradesmen and farmers, all vying for the same space, and the same wallets, as their competitors – it would have been Trevorrow’s task to keep them in line. He would have known who to watch, who gave short weight, whose produce was said to be already spoiled. He would have made sure the livestock was well tethered: it was his job to stop animals rampaging through the streets after all. He would have noted the local cutpurses and pickpockets, the thieves and maybe even discouraged the odd flashtail from touting for business[25]. But possibly nothing would have prepared him for what he saw that day:

William Trevorrow, a constable…deposed that…he observed a multitude of people: he approached and saw Wm. Hodge holding his wife Rebecca Hodge, by a straw band which passed round her waist. He heard him cry “A woman for sale! – who’ll purchase?” The prisoner, William Andrew, replied “I will”…He then bid 2s 6d and W. Hodge said you shall have her. He accordingly delivered her into the hands of [the] defendant, who paid the money and led her off in triumph…[26]

Apart from the actual act of selling one’s wife, what amazes the reader over two hundred years later is that Trevorrow, who after all was the Parish Officer, apparently did nothing to stop the transaction. Maybe he was too gobsmacked to intervene[27]. Maybe he waited until after the transaction, and the crime committed, to apprehend those concerned. Whatever his reasons, Trevorrow must have belatedly done his job: the case of the sale went to court after all. Rebecca Hodge was then cross-examined. After stating she and Hodge had married in 1798 in Woolwich and that they had not lived together for over ten years, she was asked,

Have you seen him [Hodge] during that time? I have, but was never alone with him, he having repeatedly threatened to take away my life, and has offered me for sale a hundred times…Who bought you? Wm. Andrew. – Did you know him before? I did. – Did he know your husband? He did…Where has your husband been for the last 10 years? Roaming about the country, I believe in Cornwall…How did you gain your livelihood at Penryn? By binding shoes. – Where did Andrew live? Also at Penryn. – Were you acquainted with him previous to sale? I was…[28]

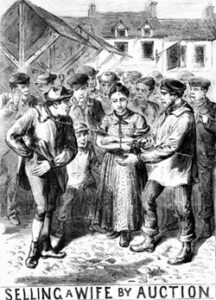

Illustration of a wife sale that took place in Bradford, 1858[29]

Illustration of a wife sale that took place in Bradford, 1858[29]

It’s apparent, then, that the Hodges and Andrew all knew each other to varying degrees: the sale begins to look less like a random incident than something prearranged. Either William Andrew wasn’t cross-examined, or the reporter failed to record anything he might have said. William Hodge wasn’t even present; the 2s 6d he made from selling his wife didn’t last long, and he was “in the poor house at Stithians” on the day of the hearing[30].

William Hodge didn’t escape the long arm of the law, however. He left Stithians workhouse in July 1820 only to go straight to gaol:

William Hodge of Redruth…indicted for selling his wife Rebecca at Redruth, to William Andrew for 2s 6d: two months in gaol…[31]

By the end of September, Hodge was out of prison and back in Stithians workhouse, where he was to shortly die. Andrew, also found guilty, received the following:

…indicted for publickly [sic] buying one Rebecca Hodge the wife of one William Hodge for 2s 6d: three months in house of correction and fined 1s…[32]

Rebecca, who had of course done nothing wrong, was allowed to go free, and must have returned to Penryn to await Andrew’s release.

There were varying reactions to the sale. First, you have the people witnessing the actual act in Redruth Market, Trevorrow’s ‘multitude’. The personal thoughts of these people are lost to us, but, as a whole, one must conclude that they were more or less complicit in the act. Not one of them stepped forward to halt proceedings (nor did Trevorrow it seems), and at least one other chancer bid for Rebecca Hodge: “Another man now offered 2s”[33]. Surely objections would have been raised, and outrages voiced, if one of those watching had felt uncomfortable with the unfolding auction? Also, none of them made Trevorrow, the Parish Officer, aware that something untoward was going down: he noticed the crowd himself, and went over to investigate. We might tentatively conclude, then, that the reactions of the lower and labouring classes to the spectacle of a wife sale was one of bemused acceptance.

No one asked William Hodge and William Andrew if they thought they were doing anything wrong (or, if they did, it’s gone unrecorded), and Rebecca’s passivity to the whole affair is almost painful in its simplicity:

…this man bought me, paid the money, and took me home, where I have remained ever since…[34]

We might add to the end of her sentence, and that’s all there is to it. If she morally objected to being auctioned off in a cattle market, she never said so in court, and the very fact that she eventually ended up marrying her purchaser, William Andrew, implies a certain level of collusion on her part.

Rebecca’s almost meek acceptance of matters contrasts dramatically with the froth dished up by the magistrates and reporters. The condemnation of the events was immediate:

It is astonishing that such disgraceful scenes are permitted. – We would earnestly recommend to the Magistrates of the District, the indicting of all the parties concerned in this shameless transaction[35].

The same newspaper called for the “full severity of the law” when cases of wife sale are brought to court[36]. Another broadsheet thought the law wasn’t severe enough when dealing with William Hodge:

…an offence so disgusting, that we hope it will never be repeated in this county, [Hodge] got off with the lenient punishment of only three months confinement at hard labour…[37]

If the above journalist judged three months hard labour as “lenient”, one dreads to think what they envisaged as a more draconian punishment. It was a sentence severe enough for William Hodge however: he was dead a couple of months later.

The case even made the London press, and was scrutinised in an equally dim light:

It is hoped that the punishment inflicted in this case, and the determination of the Magistrates to visit every such offence in future with the severity of the law, will put a stop to a practice which has latterly occurred in different parts of the country[38].

All these indictments are as nothing compared to the near-hysterical outpouring of the magistrate at the hearing, Mr Joseph Edwards[39]. It’s worth an extended quotation:

…such a breach of decency, of good manners, tending to destroy the moral feelings of a society…was a crime of no common cast, a direct violation of the laws, of religion and morality…That one man should be found to participate in such a transaction, revolting to human nature, to become a bidder in a public market for any woman…was so repugnant to the dictates of humanity…an offence of the most atrocious description…Here, in a Christian country, had the prosecutors neglected to expose the authors of so infamous an outrage, they would have been guilty of a gross dereliction of duty[40].

We can almost see Edwards, breathless and florid after his speech, eyes ablaze with moral righteousness, and Rebecca Hodge and William Andrew, in the dock, heads bowed in shame.

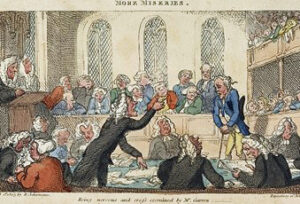

More Miseries of Modern Life: Being nervous and cross examined by Mr Garrow, Thomas Rowlandson, 1807. © Trustees of the British Museum.

More Miseries of Modern Life: Being nervous and cross examined by Mr Garrow, Thomas Rowlandson, 1807. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Or were they? Look again at Rebecca’s thoughts on the auction:

…this man bought me, paid the money, and took me home, where I have remained ever since…[41]

You can almost see her shrug her shoulders. Somewhere between these two wildly conflicting views of the same event – one matter of fact, even banal, the other apoplectic with rage – we will find the answer to the following question: why did the wife sale happen?

William and Rebecca Hodge were victims. They were, we can safely infer, victims of an unhappy marriage. They were also victims of the 1753 Marriage Act. They were victims of a society and culture that utterly refused to recognise any form of marital divorce, legally or otherwise. Rebecca was a victim of a value system so patriarchal one commentator has remarked that, during this period, “a married woman was the nearest approximation in a free society to a slave”[42]. What led them into Redruth Market in December 1819 was the acceptance of the fact that a public divorcing ritual – a wife sale – was practically their last resort at being free of each other. Which leads us to our final observation of the whole affair: the Hodges were also victims of a society and culture whose attitudes toward wife sales were becoming increasingly hostile.

It’s easy to say William and Rebecca Hodge’s marriage was a failure; a more difficult task is to ascertain why this was so. They left behind no diaries, public statements in the press, or even tweets, to give us some idea why they separated after struggling through ten years together. But we can make careful deductions.

The Marriage Act of 1753, pushed through by Lord Chancellor Hardwicke (and not without a good deal of legal chicanery, bribery, and threats), sought to finally stamp out clandestine country marriages and secret contracts, which had been the bane of petty litigation for some time. It also aimed to turn a profit, as it automatically allowed church officials to sell more marriage licences. For the first time in English Law, people under the age of 21 could only marry with the consent of their parent or guardian, and any marriage could be declared null and void unless said marriage was recorded in a Parish register and signed by the bride, groom, two witnesses and the officiating clergyman[43].

Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke (1690-1764)[44]

Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke (1690-1764)[44]

That said, the poor and labouring classes were still anxious to avoid public church weddings in their own parishes. It might have been a simple desire for privacy, or a tacit need to break the new laws by marrying without parental consent, or to commit bigamy or incest. The easiest way for couples to get a trouble-free marriage was to travel to a crowded city parish and ask for the banns to be called. Others rented rooms in a parish adjacent to their own for a month in order to legally qualify for a marriage licence. By the late 1700s, city churches were registering up to 40 weddings every Sunday, a bombardment of administration impossible to keep check on[45]. The new Act, then, swapped one set of problems for another.

In June 1798, William Hodge married Rebecca Small in St Mary Magdalene Church, Woolwich. We know from his age at death, 40, that Hodge was only in his late teens, maybe 17. Studying the register, it is apparent that the witnesses to the union – Richard Lingard and E. Edwards – were also the witnesses to several other marriages taking place in that particular church that month[46]. We can suggest that Lingard and Edwards may have been church employees, on hand to stand in as witnesses whenever yet another young couple, claiming to be of the parish, took their vows but brought only themselves along for the big day. As Hodge was underage (though he obviously kept quiet about this), and they were on their own, we can posit the argument that parental/guardian consent for Hodge to marry had not been granted – in short, their marriage was illegal, and void. It’s also doubtful, though not certain, if they ever lived in Woolwich at all. They may quite possibly have eloped, from who knows where (possibly Cornwall?), and appeared in St Mary’s to get a quickfire marriage.

London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1936: Greenwich, St Mary Magdalene, Woolwich, 1763-1826: Ancestry.co.uk

London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1936: Greenwich, St Mary Magdalene, Woolwich, 1763-1826: Ancestry.co.uk

Maybe it was the lack of parental blessing and the knowledge that they could expect no support from that quarter that put unwelcome pressure on the newlyweds. Add to this the furtive knowledge that, considering the new regulations, what they had done was also against the law, and you have two strong reasons to give as to why their relations became strained. So, whatever the truth in the matter, after soldiering on for ten years, they separated, both winding up in Cornwall; or, they had moved to Cornwall in the early 1800s, then separated. But a separation was no divorce.

And it was no divorce, because in those times, divorces did not exist. They were only legalised by the Act of 1857, making the process secular, cheaper, and allegedly accessible to all rungs of society[47]. Before this, if a couple wished to separate, there were four options open to them. They could sue in the church courts for separation from bed and board, without permission to remarry. Or, they could get a full divorce by Act of Parliament, with permission to remarry, but only if the wife had committed adultery. Third, and this was mainly the reserve of the middle classes, they could agree to a private separation by deed. Finally, for the lower orders, they could simply elope, or desert their spouse. Ill-treated women often did this, and took up with a new lover. Men would do the same, setting up with a new woman as a concubine or committing bigamy, many times leaving the abandoned wife (and any children) to the dictates of parish relief[48].

In this context, then, we can dimly see a glimmer of independence on Rebecca’s part, an independence almost exceptional for her time and station: did she leave the destitute, lame, and violent William Hodge and take up with William Andrew of her own accord? From the point of view of our times, who can blame her?

Hodge, we now know, was a criminal and violent. He knifed at least one fellow workhouse inmate, assaulted others, and seems to have spent the last years of his life either in a poor house or in prison for various offences[49]. Rebecca’s statement at the hearing, that she was “never alone with him, he having repeatedly threatened to take away my life”[50], is entirely plausible given what we know of his disreputable character. If she didn’t lie about where she and Hodge were originally married – and we have proven she didn’t[51] – then it follows she was probably honest when remarking on her husband’s attitude towards her. Combined with the possible pressures on their marriage outlined above, it’s reasonable to assume, then, that Rebecca deserted the inadequate, murderous Hodge, rather than the other way round.

Hodge’s dubious personality notwithstanding, this was a massive step for a married woman in Georgian England to take. The prevailing religious and educational dogma taught all levels of society that marriage was sacred and an act of God – which explains why there was no such thing as divorce. This indoctrination kept many marriages together: to leave your spouse was to defy God. External checks kept relationships on an even keel too; the close-knit social relations and inquisitive village culture of the time ensured, or tried to ensure, that a marriage was for life[52]. In leaving Hodge, Rebecca was turning her back on God and society.

Besides this, a separated wife had no legal status whatsoever, unless the separation was protected by a private deed. All and any income from the wife’s estate could be retained by her estranged husband. All her personal property and any future income could be seized, at any time, by her husband. Any savings she might have squirreled away, belonged to her husband. She was unable to enter into a legal contract, use credit or borrow money, or buy and sell property. Any children she may have had by her husband were answerable only to their father and could be seized by him at any time. The estranged husband’s influence could also extend beyond the grave, with the wife’s estate, property and income liable to be claimed by any relatives in the event of his death[53]. In leaving Hodge, Rebecca was also forsaking any legal rights she might have had – and what she did have wasn’t much.

At some point when trying to make a new life with William Andrew, Rebecca must have realised that she would never be free of William Hodge. That she told the magistrate that she had seen Hodge after their separation, and that he and Andrew were known to each other, is significant[54]. Maybe Hodge, when not housed in one institution or another, had taken to visiting his wife and her new lover, asking for handouts, issuing threats, pleading sympathy, or just generally being unpleasant. He could have justifiably sued Andrew for criminal conversation and levied crippling damages on the couple[55]. If this is so, he must have been a genuine menace, and upsetting for Rebecca, not to mention William Andrew: anything Rebecca had achieved since leaving her husband could have been claimed at any moment by Hodge, which is possibly a point he maliciously enjoyed making to her. Something had to be done. Rebecca and Andrew were in agreement, but what of Hodge?

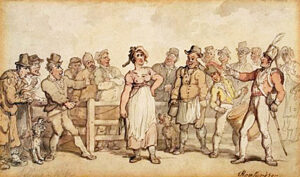

Selling a Wife, by Thomas Rowlandson[56]

Selling a Wife, by Thomas Rowlandson[56]

Seeing as he had “offered” Rebecca “for sale a hundred times”[57], he may have taken little convincing. He himself would have been liable to arrest for any debts run up unbeknownst to him by his wife, and he would have definitely wanted to avoid yet another spell at His Majesty’s pleasure[58]. Some estranged husbands took steps to avoid this by making a public statement, absolving themselves from any and all of their errant wife’s financial wrongdoings and threatening litigation against those that sought recompense from him. It’s what Richard Conning, of Redruth, did in 1821[59]. But taking out a notice like this in a broadsheet cost money, and Hodge was not a man of means. A lesser worry of his would have been that, in the event of his death, Rebecca could claim a third of his estate as a dower[60]. It’s very doubtful Hodge had any estate worth the mention, so it’s extremely likely he was a willing participant in Rebecca and Andrew’s plan, one that would “give public recognition to a prearranged agreement between all three parties”[61]. And, lest we forget, he stood to make a tidy profit.

What the three of them conspired to do in order to break their ties with the past was of course the wife sale, “popularly believed to be a legal and valid form of divorce”[62]. Though “in the eyes of the law the rite of wife sale was a non event”[63], many of the lower and poorer classes held the firm belief that, if certain protocols were observed on the part of those arranging the auction, a wife sale was a perfectly acceptable manner in which to sever all marital, personal, and financial ties with an unwanted spouse: it was a legitimate form of divorce. In 1857, shortly after the passing of the Divorce Act, a magistrate presiding over a case of alleged bigamy “took the opportunity” of

…cautioning persons from believing in the absurd notion which is held by the illiterate, that if a man chooses to offer his wife for sale…he is at liberty to do so. [The magistrate]…hoped the new divorce law would set matters on a better footing[64].

A reporter in the London Advertiser put it more bluntly:

Ignorant people seem not aware that so gross an outrage of decency is punishable by law, and that persons have been convicted of the crime and punished accordingly[65].

So inculcated was the notion that wife sales were a genuine form of divorce, one sale in 1820 was declared to be undertaken in Smithfield Market “according to law”[66]. Incidentally, this is why neither Rebecca nor Andrew were charged with bigamy at their hearing: to do so would have made wife auctions a legal reality.

Legal or not, wife sales had been a sporadic, but established, part of rural life since Norman times, and cases were still being recorded in the early 1900s[67]. They were an invented tradition, a

…set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past…they are responses to novel situations…[68]

The novel situation many unhappily married people found themselves in, was that there was no legal form of divorce: marriage was for life, and that was that. Gradually, over time, a set of practices evolved to enable couples to separate relatively painlessly and without the threat of their pasts coming back to haunt them. The wife sale was the invented tradition that the menage à trois of Rebecca, Hodge, and William Andrew turned to in 1819.

Upper Fore Street, Redruth, c1890. Kresen Kernow, corn04197

Upper Fore Street, Redruth, c1890. Kresen Kernow, corn04197

They may have individually, or collectively, sought – or have been offered – advice on how to go about the ritual; it’s not inconceivable one or more of them actually witnessed a sale themselves. Although their sale was “the first of the kind at Redruth”[69], the magistrate at their hearing, Mr Joseph Edwards, remarked (amongst other things) that

Very few [wife sales] had occurred in this [county], and that only within the last year or two…[70]

Their transaction took place during one of the peak decades of documented auctions[71], and indeed featured the most important hallmarks of a classic wife sale[72]. There may have been more acts and rituals involved here that were also typical of a sale, but the reports do not include them.

That the sale took place in Redruth Market is crucial to the legitimacy of the sale. A public place, a “nexus of exchange”[73], in full view of the community, was vital to conferring verisimilitude on the transaction. In 1789 it’s recorded that a wife in Thame had to be re-sold as her original sale hadn’t taken place in the market[74]. Although decidedly barbaric to our refined sensibilities, the use of the halter was deeply symbolic and probably derived from the tethering/untethering of livestock and/or property purchased at market. After all, in the culture of the times, a wife was little more than a husband’s property. Also, the delivery of a wife in a halter to her purchaser symbolised to all observing that the husband was completely surrendering the possession of his wife to another, and that he was a willing (or resigned) party in this surrender. All this publicity was also essential in displaying the wife’s consent to the auction – and Rebecca must have had good reason to be a willing participant[75]. Although she described herself as being “confused”[76] during the auction, Rebecca may have been as complicit in the whole affair as the lady in Thomas Rowlandson’s painting Selling a Wife (1812-14, above), if perhaps not actually grinning openly. Or, alternatively, she might have felt completely degraded – as no doubt many women did – by the proceedings and wanted to get the formalities over with as quickly as possible. There’s no way of knowing.

Other typical features we may observe are:

- i) The form of auction. Hodge presented Rebecca for sale in an open marketplace; those present observed the form of the ritual and recognised it as an open sale – though they may have equally realised that the identity of the winning bidder was a foregone conclusion. (In Smithfield in spring 1820 a wife sale was actually advertised like a formal auction by way of handbills posted in different parts of the town, declaring that bidding would begin outside a pub at 3pm sharp[77].) Though we know one other man bid for Rebecca – “Another person now bid 2s” – and that Andrew was forced by Hodge to up his bid from 2s 3d to the final price of 2s 6d[78], this was very possibly stage-managed, with the money agreed for in advance, and the other bidder a fellow-conspirator in the sale, pressed upon (and probably assured of a good drink later) to give authenticity to the whole affair[79].

- ii) The exchange of money. This, of course, had to take place at the conclusion of the auction, from purchaser to seller, in public view. As Trevorrow deposed at the hearing, Andrew did indeed pay “the money”[80], in Redruth Market, in full view of the gaggle of spectators.

iii) The solemn transfer of the woman from her seller, or husband, to her new owner. Andrew received Rebecca from Hodge, “and led her off in triumph”[81], presumably by the halter. Sometimes the sale was toasted by those involved in a local tavern; in Canterbury in May 1820 a labourer, “or rather brute”, sold his “rib”, a “buxom young woman”, and then “seller, purchaser, and purchased” repaired to the nearest tavern for a celebratory libation[82]. It’s unclear if this was the case with our wife sale and, if our previous conclusions are in any way accurate, unlikely.

The most plausible scenario of what took place after the sale is the one given by Rebecca herself: Andrew “took me home, where I have remained ever since”[83]. She and her new ‘husband’ returned to their lives in Penryn, and Hodge, with the coins jingling in his pocket, went back to his. All three must have been convinced of the correctness of their actions, and would be delighted with the outcome: for a not extravagant sum and a short, sharp spell of public discomfort and scrutiny, Hodge and Rebecca were finally free of each other and could go about their lives without interference from the other. And there, the story might have ended, were it not for the fact that Hodge and Andrew were both indicted and, with Rebecca, received summons to appear at the Quarter Sessions[84].

It’s with great irony that we actually know anything about this wife sale at all. If it had occurred a hundred, or maybe even fifty years earlier, its very existence would have probably remained forever unknown to us, and I wouldn’t be telling you about it. The onset of the Industrial Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the birth of the Empire changed British culture and society forever[85]. Wife sales, with their close resemblance to, and associations with, peasant customs and folk belief, had no place in the petit-bourgeois hegemony[86].

Evangelical sensibilities prevalent in many echelons of society at this time also brought-about a sea-change in attitudes to wife sales. Previously, for example in the early eighteenth century, wife sales had been grudgingly viewed with a level of tolerance by the relatively lax church and civil authorities as a convenient method of popular divorce[87]. By 1819, Methodism had taken firm root at all levels in Cornwall, reforming hearts and minds, a precursor to the stereotypical view of prudish Victorian England. There’s little doubt that what the disciples of Wesley (and Wesley himself) discovered on their pilgrimages to West Cornwall in the 1700s was a lawless, godless land of smugglers, wreckers, cut-throats and thugs – or rather, that’s what the Wesleyans portrayed the Cornish as, though maybe not without some accuracy[88]. In 1750 the wreckers of Breage actually dispensed with the method of luring unsuspecting ships (and crews) to their doom on the rocks by means of false lights, and attacked a vessel safely at anchor off the nearby coast[89]. Such shameless bravado, along with wife sales, was soon to be exorcised by the advent of the Wesleyan mission.

More jocular accounts of wife sales such as the one above were shortly to become obsolete[90]

More jocular accounts of wife sales such as the one above were shortly to become obsolete[90]

The improvements in education and literacy during this period gave birth to a reading public in England, and the improved mechanisation of printing presses generated a boom in the publication of newspapers and professional journalism[91]. All this served to give greater visibility to criminal cases and scandals – crime sells newsprint, and a report of a juicy wife sale could be guaranteed to fill discussion columns. For example one reader of the Cornish Telegraph felt moved to comment on the frequency of wife sale reports in 1864[92]. In the 1700s and slightly later, such things were quietly tolerated and not deemed newsworthy, and in any case journalism was in its infancy: a reported case of the removal of children from a parish in Lincolnshire in 1819 uncovered the fact of a wife sale that had taken place nearly twenty years previously, but had never been recorded at the time or made it to court[93].

Paradoxically, therefore, as coverage of wife sales increased, public opinion swung against them. The sale in Redruth Market was as marketable to journalists as it was scandalous, and the story appeared, with characteristic opprobrium, in at least three London newspapers[94]. Due to the changing way in which society now viewed wife sales, they truly went underground in the late 1800s[95]. From being a public event, sales now took place in the back rooms of taverns, or in quiet country lanes: under 10 sales are recorded in England in the 1890s[96]. This is why a contemporary review of Thomas Hardy’s novel The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), which of course opens with a wife sale from the early 1800s, can remark of it that this

…is a perfectly credible transaction, especially at the period chosen by the author[97].

Credible in the early 1800s maybe, but a thing of the past barely eighty years later.

It is not the purpose of this essay to discuss the “slippery”[98] nature of the evidence of wife sales, or whether the frequency with which reports of sales appeared in the press are a true barometer of actual sales[99]. Without the newspaper reports, we would know next to nothing of the wife sale that occurred in Redruth in 1819. Tracing the lives of William Hodge, Rebecca, and William Andrew and what motivated their actions in the Market that day would have been impossible had not these actions been deemed morally outrageous and, therefore, newsworthy. Society’s condemnation of their desperate attempt to forge a fresh start and a clean break for themselves – an attempt they clearly believed to be legitimate – has ironically given us a window into their lives, and a window into a society utterly ‘divorced’ from our own.

It may be a good thing that this part of Redruth Market’s past cannot be recreated.

2 https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/redruth-buttermarket-purchase-marks-further-773274

3 See: https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/redruth-revival-breathing-new-life-3107730 , https://cornishstuff.com/2020/06/22/redruth-wins-heritage-action-zone-money/ , https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1475141 , and https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cornwall-57332236

6 https://redruth-revival.org/history/

7 https://redruth-revival.org/history/

8 Royal Cornwall Gazette (RCG), 18/10/1810, p3

9 RCG, 2/7/1841, p4

10 RCG, 30/7/1847, p2

11 RCG, 1/2/1834, p4

12 RCG, 16/8/1844, p4

13 RCG, 21/12/1849, p6

14 RCG, 28/3/1835, p2

15 RCG, 10/4/1840, p4

16 RCG, 21/7/1848, p3

17 RCG, 22/3/1844, p3

18 Falmouth Express and Colonial Journal, 7/12/1839, p4

19 See: Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital 1848-1875, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962, p173-92, and John Rule, Albion’s People: English Society 1714-1815, Longman, 1992, p21-5

20 RCG, 1/12/1848, p2

21 https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1475141

22 Joyce M. Ellis, The Georgian Town 1680-1840, Palgrave, 2001, p90-3

23 Truro Quarter Sessions, 27/4/1824. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/10/561

24 RCG, 8/6/1822, p3

25 Falmouth Express and Colonial Journal, 7/12/1839, p4

26 RCG, 5/4/1839, p4

27 West Briton (WB), 17/12/1819, p2

28 Image from: https://londonopia.co.uk/the-wife-auctions-of-spitalfields/

29 Cornishman, 14/4/1949, p4

30 See: E.P. Thompson, Customs in Common, Penguin, 1991, p404-66, Lawrence Stone, Road to Divorce: England 1530-1987, Oxford University Press, 1990, p141-7, and Samuel Menefee, Wives for Sale: An Ethnographic Study of British Popular Divorce, Basil Blackwell, 1981

31 https://cornishbirdblog.com/2019/10/08/wife-selling-in-cornwall/

32 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3, and WB, 14/4/1820, p2

33 London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1936: Greenwich, St Mary Magdalene, Woolwich, 1763-1826: Ancestry.co.uk

34 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

35 ibid.

36 RCG, 20/1/1816, p2

37 RCG, 19/4/1817, p2

38 Lostwithiel Quarter Sessions, 12/1/1819. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/9/252

39 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Poor_Laws, and John Rule, Albion’s People: English Society 1714-1815, Longman, 1992, p116-35

40 Image from: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Victorian-Workhouse/

41 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

42 Cornwall Parish Clerks Online, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/

43 ibid.

44 ibid.

45 ibid.

46 Image from: https://www.vanel.org.uk/cleecops/policing-in-cleethorpes/parish-constables/

47 RCG, 2/11/1833, p2

48 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parish_constable

49 Lostwithiel Quarter Sessions, 15/1/1822. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/10/277

50 RCG, 2/3/1822, p3

51 RCG, 5/4/1839, p4, and 18/10/1839, p2

52 RCG, 14/10/1842, p2. A Redruth prostitute was imprisoned for drunkenness. By the 1860s Redruth was believed to contain the most courtesans in Cornwall. See: John Van Der Kiste, A Grim Almanac of Cornwall, History Press, 2009, p44-5

53 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3. The initial report (WB, 17/12/1819, p2) has it that the straw band was round Rebecca’s neck.

54 A wife sale at Smithfield Market was broken up by more diligent – and numerous – representatives of law and order in 1820. As reported in the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 1/5/1820, p4.

55 ibid. Rebecca stated her husband cried “I have a wife to sell!”, rather than, as Trevorrow said, merely a “woman”.

56 Image from: https://bradfordmuseums.org/wife-selling-in-victorian-bradford/

57 See note 54.

58 Lostwithiel Quarter Sessions, 11/7/1820. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/10/86. Also reported in RCG, 15/7/1820, p4. Hodge is curiously described here as a carpenter.

59 Truro Quarter Sessions, 11/4/1820. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/10/60

60 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

61 ibid.

62 WB, 17/12/1819, p2

63 WB, 14/4/1820, p2

64 RCG, 15/7/1820, p4. See note 52: The Quarter Sessions Rolls has it that Hodge was sent down for two months.

65 British Press, 19/4/1820, p4

66 Edwards was born in 1772 in Phillack, and died in Truro, in 1834. See: Cornwall Parish Clerks Online, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/. His will is held by Kresen Kernow, ref. SHM/761

67 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

68 ibid.

69 Lawrence Stone, Road to Divorce: England 1530-1987, Oxford University Press, 1990, p13

70 ibid., p121-8

71 Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Yorke,_1st_Earl_of_Hardwicke

72 Stone, p129

73 London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1936: Greenwich, St Mary Magdalene, Woolwich, 1763-1826: Ancestry.co.uk

74 Stone, p368-82. In practice, divorce was still “wholly inaccessible to the lower middle class and the poor” in this period. (p372)

75 ibid., p141-3

76 See notes 34-6

77 RCG, 15/4//1820, p3

78 See notes 30-1

79 Stone, p1-8

80 ibid.

81 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

82 Stone, p143

83 Image from: https://lichfieldbawdycourts.wordpress.com/2019/09/30/wife-selling-diy-divorce-18th-century-style/

84 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

85 Stone, p143

86 RCG, 28/4/1821, p1

87 Stone, p143

88 ibid., p145

89 Samuel Menefee, Wives for Sale: An Ethnographic Study of British Popular Divorce, Basil Blackwell, 1981, p1

90 E.P. Thompson, Customs in Common, Penguin, 1991, p452

91 Cornish Telegraph, 21/10/1857, p2. Rebecca, in being able to sign her name, was one, at least, literate person who believed in the ritual of wife sale.

92 28/9/1819, p3. This in reaction to a sale in Smithfield Market.

93 Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 1/5/1820, p1. The emphasis, tellingly, is the newspaper’s.

94 Menefee, p2

95 Eric Hobsbawm, in Eric Hobsbawm and T. Ranger, eds., Inventing Traditions, Cambridge Books Online, 2012, p1-2

96 WB, 17/12/1819, p2

97 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

98 Stone, p145. There were 40 recorded instances of wife selling in the decade 1810-9. E.P. Thompson records 218 between the years 1760-1880 (p409)

99 See Thompson, p418-26

100 ibid., p418

101 ibid., p420

102 ibid., p419-21

103 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

104 Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 1/5/1820, p4

105 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3. Hodge is supposed to have said to Andrew’s first offer, “she shan’t go for that”.

106 See E.P. Thompson’s similar conclusions to Rebecca’s sale, p428

107 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

108 ibid.

109 St James’s Chronicle, 16/5/1820, p1. This article condemns the sale as “disgraceful and demoralizing” at the same time as employing such chauvinistic language when describing the purchased female.

110 RCG, 15/4/1820, p3

111 Lostwithiel Quarter Sessions, 11/7/1820. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/10/86. Also reported in RCG, 15/7/1820, p4.

112 See Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962

113 Menefee, p5-7

114 See Thompson, p442-4, and Stone, p144

115 See: Joanna Thomas, Lost Cornwall: Cornwall’s Lost Heritage, Birlinn, 2007, p1-23, John Rowe, Cornwall in the Age of the Industrial Revolution, Second revised edition, Cornish Hillside Publications, 1993, p34-6, 67.1-67.40, 261.1-261.48, and Philip Payton, Cornwall: A History, Cornwall Editions, 2004, p197-206

116 As recounted in Rowe, p36. On Cornish wrecking in general, see Thomas, p164-186

117 Image from: https://digital.nls.uk/english-ballads/archive/74895268?mode=fullsize

118 See: Raymond Williams, The Long Revolution, Chatto & Windus, 1961, p156-213

119 13/1/1864, p4

120 British Press, 6/2/1819, p4

121 British Press, 19/4/1820, p4, Morning Chronicle, 20/4/1820, p4, and National Register (London), 23/4/1820, p3. The National Register ran the story again the next day: 24/4/1820, p3.

122 Thompson, p455-6

123 Stone, p145, and 146-7, 248-55

124 St James’s Gazette, 5/6/1886, p7

125 Thompson, p410

126 ibid., p404-16

Francis Edwards runs ‘The Cornish Historian’ website and blog (https://the-cornish-historian.com/), rated one of the top fifty sites on Cornwall. A Camborne boy, he has a BA and MA in literature and a lifelong love of history. Francis generally covers the Industrial Revolution and mining, crime, social unrest and sport. He welcomes commissions for articles, and talks for local history groups.