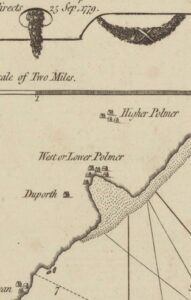

I suppose it’s safe to say, that over the years I have written a fair bit about the premier port of St Austell Bay, the port of Charlestown. The name ‘Porth-Meur’ or ‘Great Cove’ had been used for several hundred years, evolving through time, to become Porthmear, later Polmear, and later again, West Polmear. This was done to distinguish it from the settlement of Polmear at Par. In the years before Charles Rashleigh purchased the land in 1779, small wooden vessels had beached themselves and had taken onboard cargos of copper and tin ore and the odd shipload of china clay and china stone. These little vessels had used the beach at Polmear for approximately 70 years to unload and load their cargo. The small schooners and ketches were drawn up at high water, giving them a 48-hour window for unloading or loading their cargo or ballast.

Part of an old map by Sawyer from 1779 showing no port yet built at Polmear. The name of West or Lower Polmer is clear to see.

Part of an old map by Sawyer from 1779 showing no port yet built at Polmear. The name of West or Lower Polmer is clear to see.

An anchor would be dropped outside of the low water mark and the ships would then beach at high water and as the tide ebbed, they would go about their business. The following day, when the loading was completed, they would haul themselves back off the beach using the anchor dropped the previous day. The beach was open to the elements, and many an experienced captain and crew have fallen victim to tempestuous weather whilst aground there. Many vessels were caught out and wrecked and many lives were sadly lost.

Copper ore can be seen in this photo stored in the ore Platts or Hutches, these hutches divided up the dockside in the first 90 years. Two walls remain today at the seaward end. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Copper ore can be seen in this photo stored in the ore Platts or Hutches, these hutches divided up the dockside in the first 90 years. Two walls remain today at the seaward end. Lyndon Allen Collection.

A local entrepreneur, Rashleigh,1 was a visionary, and he had many business interests including mining and shipping ventures. Coal was abundant in Wales and metal ore was shipped there to be smelted. After so many losses of vessels to the beach, Rashleigh decided to build a granite pier to afford protection for shipping. It also provided shelter for the local fishing fleet. Construction began in earnest in the year 1791 after he had sought advice about the construction from the doyen of modern-day engineering, John Smeaton2. Charles Rashleigh quarried his granite, or ‘Moorstone’ as he called it, locally. It came from Carn Grey quarry, which was at the top of the steep hill out of St Austell, near Carclaze. It was downhill all the way to the proposed port. Individual stones were loaded onto carts and dragged out of the quarry and brought down the hill to Polmear. I have proof to back up this claim from senior geologists and a world authority on granite. It was not from Luxulyan Quarry as many historians have previously suggested. Once the harbour building had begun, in the spring of 1791, things quickly began to change for the nine-fisher folk who lived in the tiny cluster of dilapidated buildings there. New houses were suddenly being built. The year Rashleigh started building the western quay, shelter was afforded to fishing vessels in tempestuous weather, three homes were built and in that year the population increased to 26 people.

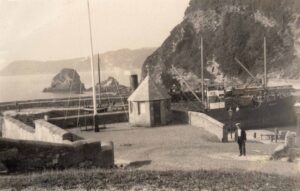

The open beach at Polmear afforded little or no shelter to vessels beached there. Vast amounts of copper and tin were shipped from the port. The remains of the Appletree copper Mine engine house can be seen on the headland in this photograph. Lyndon Allen Collection.

The open beach at Polmear afforded little or no shelter to vessels beached there. Vast amounts of copper and tin were shipped from the port. The remains of the Appletree copper Mine engine house can be seen on the headland in this photograph. Lyndon Allen Collection.

The following year, 1792, saw a more vigorous extension of the work. A new pilchard seine3 was started, a ropewalk4 was established and works on the pier continued. Further rocky ground was excavated to form a basin, several additional dwellings and a fish cellar5 were built. The village now also had an inn called ‘Three Doors’ (now, 21 Charlestown Road) and the population had soared to 97.

In 1793, shipbuilding was established at the port and several small vessels were launched during that year. The inner basin was opened to receive small vessels, some expanses of common land were enclosed and seven additional homes were built. The population increased again, to 109.

The year 1794 saw the basin further enlarged to accommodate vessels of 220 tons burthen. A limekiln6 was built on the harbour where the roundhouse stands today and a gun battery was constructed to protect the port against our long-standing adversaries, the French. 11,000 bushels7 of lime were burnt and a further seventy acres of common land was enclosed. The population increased again to 163 and several businesses including fish cellars, sailmakers, ship chandlers, and wheelwrights became established.

In 1795, 15,000 bushels of lime were burnt, six acres of wheat were harvested and a brickworks was established. The basin was further enlarged to enable vessels of 600 tons to enter and the number of villagers increased to 175.

Loading cargo on the banjo quay was a regular occurrence around the turn of the 20th century. I have several photos of different vessels unloading or loading cargo there. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Loading cargo on the banjo quay was a regular occurrence around the turn of the 20th century. I have several photos of different vessels unloading or loading cargo there. Lyndon Allen Collection.

In 1796, 21,000 bushels of lime were burnt and added to the land. The basin was still being enlarged and flood gates were erected to the outer piers so that vessels could float in in the absence of tide. This floating dock was the only one of its kind this side of Bristol. At the inner extremity of the basin, another excavation had begun to form a graving dock8 for repairing vessels.

I have a theory about when the name changed from Polmear to Charlestown. Maritime historian Richard Larn OBE and others say 1801 but I have proof that the change was before that. In a newspaper article, the name of ‘Charlestown, near St Austell’ was mentioned in October 1798. It is also written on the saucer of the Duporth Cup9. This little cup shows hand-painted scenes of the construction of the port. It was made and presented to Rashleigh for some remarkable achievement, but what achievement, the building of the basin or the completion of the port itself? We may never know, but I think it was given upon completion of the basin. After all, that was the first significant landmark occasion. The five scenes depicted on the cup don’t include a dock and surely this would have been added if it had been partially or even fully constructed? The dock was constructed from 1796 onwards and the completion of the port would surely have had other scenes, and perhaps a bigger cup may have been made to accommodate that. So I think the name change is five years earlier than everyone else thinks. Even then, the change was verbal and not drawn up on paperwork.

The year 1797 saw two ships launched from the shipyard and the inhabitants of the village numbered 205.

The steel topsail schooner Mary B Mitchell at Charlestown in 1928. Lyndon Allen Collection.

The steel topsail schooner Mary B Mitchell at Charlestown in 1928. Lyndon Allen Collection.

In the following year, 1798, the graving dock was enlarged, so that several vessels could be accommodated, and several houses were either being built or had been completed.

During 1799 the basin was further enlarged, gates were placed to the graving dock and the number of people living there is given as 234.

During 1800 there was further enlargement of both basin and dry dock. A further fifty acres of common land was enclosed, and the population grew to 252.

The dock and basin were finally completed in 1801. The length of the floating dock available for wharves on either side was about 100 yards, convenient ore plats were provided on the dockside with sheds for china clay, and at the head of the basin stood two docks for the repairing of small vessels, with a building yard at the head of one of them run by William Pearse Banks. However, Charles Rashleigh would not recognize what we know as a dock today. Today’s dock is much larger than that of 1801. This is because it was further extended during the years of 1873 and 1874.

Harbour master, William Hendra, is pictured standing below the turning triangle. A vessel is discharging coal on the big pier, something I thought to be a rare occurrence. However, it was common practice up until WW2. The photo dates from 1928. William was formerly a dock porter but took on the harbour master’s job in 1928, he retired in 1950. He had worked for Charlestown Estate for over 50 years.

Harbour master, William Hendra, is pictured standing below the turning triangle. A vessel is discharging coal on the big pier, something I thought to be a rare occurrence. However, it was common practice up until WW2. The photo dates from 1928. William was formerly a dock porter but took on the harbour master’s job in 1928, he retired in 1950. He had worked for Charlestown Estate for over 50 years.

Over hundreds of hours of laborious research, I finally have the evidence to back up my claim about the further use of materials excavated to form the dock and basin. Previously, many historians have claimed that it was taken into St Austell for building materials but I never believed that. Just like the claim made by A L Rowse that the Charlestown brothel was at 11 Doors Lane, next to where all the well-to-do of the village lived. I never bought into that either. For 30 years I thought the rock was blasted, before being loaded onto waiting barges. It was then pulled out to sea on a long rope pulley system or transported by boat and dumped about half a mile offshore. There is a vast reef of rock and shale there now called the ‘Rougth’. This enabled ships to anchor safely without the worry of their anchors dragging. Also, these rocks would have improved fishing prospects for the growing community. An increasing population had to be fed. Food had to be farmed, hunted, or caught, and vegetables grown. I now have in my possession a map dated 1779 which clearly shows the area of the Rougth, marked then as coarse sand. Today it’s all rock, so in 1779, there were no rocks there, just as I always suspected.

As the port evolved, things started to change regarding cargo and cargo handling. The eastern dockside gradually developed over around 100 years. Initially, mostly metalliferous ores were shipped out but the process of loading was slow and laborious. Vast areas of the village were turned into ore floors. A stone base was created for these floors using the ballast stones taken off the ships. These ore floors were identical in size, and originally there were four or five in number, this rose to seven over time. The ore was piled up on them in large quantities. The only remaining example of an ore floor that can be seen today, forms part of the Rashleigh Arms car park. For example, an 80-ton small schooner may have to carry nearly ten tons of ballast during the winter. Ore floors created a large storage area and this kept the quaysides relatively clear. Ore ‘hutches’ or ‘Platts’10 were constructed to facilitate the storage of hundreds of tons of ore. This was piled from the edge of the dockside up to Quay Road (then Captains Row). During many years of research, I have built a list of over sixty different cargos. Everything from cannon balls for the Battery, Ordnance Stones, Guano (bird poo) from Chile, barrels of gunpowder, and even live animals. These cargos remained as the bread and butter for the port during those formative years. A rapid increase in demand for the new cargo, ‘china clay,’ meant things were about to significantly change. China clay was expensive to produce at this time. Early clay producers relied on solar energy to dry the clay in pools. These pools were around 12 feet wide and circular, and also about three feet deep. Once the water had evaporated from the heat of the sun, the clay was broken into chunks for transportation to the port. The main challenge for the china clay proprietors was to get it to its desired destination, namely the potteries of Stoke-on-Trent. The costs involved were expensive, to say the least. The early pits around St Stephen and St Dennis were nine miles from Charlestown which was the port of choice for shipment. Even if you had that dried product you had to get it to the port, so wagons and horses were required. Then it had to be loaded onto a ship to make the arduous journey down around Land’s End and up to the northwest ports of Liverpool, Manchester, or Runcorn, unloaded, and then loaded again onto barges to make the thirty-mile journey inland via canal to the potteries. This, of course, was not cost-effective, so shipments were few and far between at that time. However, by the time the Cornish metalliferous mining industry collapsed in 1880, clay was more affordable and easier to produce. As time went on, improved methods employed in the production of china clay began to have a positive effect. Clay became cheaper to produce and there were a few reasons for this. Firstly, clay could be dried in purpose-built drying sheds known as dryers. Secondly, hydraulic mining had now become normal. The rock face was now blasted with high-power hoses called monitors. The slurry clay was piped away to holding or settling tanks at the back of the vast drying sheds before being laid out on the drying floor. Under the floor, there was a void and at one end of the building there was a furnace fired by coal and at the other, a flue. Hot air was circulated under the floor via a bellows and the clay above was dried. Once dry, it was sent to Charlestown for shipping. It seems amusing to me, that anything moved by road on a vehicle like a truck is a shipment, but if taken by boat is cargo.

The harbour only allowed a maximum of fifteen vessels to berth in the dock at any time. Once the gates were opened, usually an hour before high water, it was the dock master’s job to get the ships ready for departure in turn and the ship with the shallowest draught went first. At the top of high tide, it was the turn of the deepest ship to depart. Once the tide started going out, the process was reversed. The same process was used for ships coming into the harbour although two vessels could wait, berthed stem to stern alongside the entrance to the dock gates. This sped up the job of the ‘hobblers,’ the men whose job was to warp11 the vessels into the harbour. The gates were then closed an hour after high water. This job was overseen by the master hobbler. Charlestown at this time was a busy port with many movements every tide.

Businesses were now starting to thrive and merchants of all kinds were plying their trade around the harbour. Fortunes were there for the making and people such as shipping merchant Thomas Stephens, became very wealthy men. A school was opened in the residence now known as the ‘Beeches’. It was called the ‘Villa’ School and had a large lawn which became the village playing field and tennis courts. As a private school, it finally closed its doors around 1850. The building then reverted to a dwelling for Matthew Luke, the shipyard owner.

Dockmaster William Hendra (rowing) with an unknown Trinity House Pilot in 1928. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Dockmaster William Hendra (rowing) with an unknown Trinity House Pilot in 1928. Lyndon Allen Collection.

In 1804, a small iron foundry was built but its location remains unknown. In the 1820s this foundry was demolished. Then, in 1827, a new building was erected adjacent to the leat near the top of the ‘Great Charlestown Road’. Charlestown Foundry was used continuously until 1996 when it closed and at that time it was the only building in the village still being used for its original purpose.

By now, the population of the village doubled every year. Great Crinnis Mine was the leading copper-producing mine in the world and a large percentage of its ore was shipped out through Charlestown. Charles Rashleigh had a considerable stake in Polgooth Tin Mine, about three miles away, and a significant amount of its ore was brought to Charlestown by horse and cart for shipping. I have written in great depth about Carclaze, Great Crinnis, and Polgooth Mines in my books. Other cargoes were imported for the ever-expanding village and the surrounding area: timber for building and limestone which was burnt to scatter on the fields to improve the soil quality. Other cargos included salt to preserve pilchards for export, cow hides which were made into horse harnesses and saddles and vinegar for the malt houses. Ordnance was also essential for the Battery including cannon balls, fuses, detonators, and muskets.

The Hendra family outside of number 2 Quay Road, the name above the door in French because of the huge amount of French vessels from Nantes using the port. Lyndon Allen Collection.

The Hendra family outside of number 2 Quay Road, the name above the door in French because of the huge amount of French vessels from Nantes using the port. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Coal was also a vital ingredient for the drying process in the rapidly expanding china clay industry. Previously the china clay wagons rolled through the town of St Austell to the port and then returned to the pits mostly empty but now they would return laden with coal from the Welsh Valleys. Imports of coal soared.

It’s fair to say that at this time in the port’s colourful history, the living conditions were quite literally, hell. This piece of text from a book called The Cornish Coast and Moors by A.G. Folliott-Stokes was written in 1912. It is quite shocking to think that this was just before World War One.

“Hades: A little way beyond Porthpean Cove we passed a large house standing in a small park. Then traversing a little plantation we saw beneath us the clay and coal port of Charlestown. This place used to be called Polmear. Then its name was changed in honour of an unfortunate King. And now it should be changed again to Little Hades. The smoke of its torment ascended in heavy clouds of black and white dust as we scrambled down the steep hillside into the gruesome pit, where a crowd of undistinguishable beings are forever emptying and loading an inexhaustible fleet of schooners. What the natural features of Charlestown originally were it is impossible to say, for everything is coated with white or black dust, and sometimes with both together, the result being a most depressing grey, as of ashes. Grass, trees, flowers, houses, and people, all share the same fate. Nothing escapes, and the result is indescribable. How anyone can be persuaded to work, much less live in such a nightmare of a place, we cannot imagine. But what will not necessity compel men to do? It was, we must admit, blowing half a gale from the eastward when we were there, after a month’s drought, so probably the conditions were worse than usual. Let us hope so. At first, we could see nothing, but gradually our eyes accustomed themselves to the murk, and we made out that on one side of the harbour, vessels were being loaded with china clay, and their crews were as white as flour millers. On the other side, coal was being discharged, and here the crews were as black as Erebus. The villagers, and those not immediately concerned with the shipping, were black or white, according to which side of the port they resided on. Whilst some were both black and white, like magpies. It was more than we could stand. We went into an inn for tea. We were shown into a small room mathematically square. The one window was closely shut because of the dust, though the shade temperature was over 70°. Despite this, there were white film-covered chairs, a table, a mantelpiece, a piano, and artificial flowers. On one of the walls was a tragic rendering of the Deluge, arms, legs, and heads being hopelessly mixed up with tree trunks and domestic furniture. It was all the most depressing. After tea, we staggered out and stumbled up against a man carrying a large shovel over his shoulder. His face and clothes were the colour of ashes. ‘How on earth do you fellows manage to live and work in such an appalling atmosphere?’ we asked in a husky voice.

‘Well, boss,’ was the prompt and equally husky answer, ‘we couldn’t do it if it warn’t for the beer.’

We left this champion of our national beverage with a feeling of respect. His hearty faith in any vital principle in such a veritable Gehenna was most stimulating. About two miles inland from Charlestown is St. Austell, a thriving market town with a fine church, but we had not time to make a detour to visit it. As we climbed out of Charlestown, we gleefully shook her dust from our feet.”

During the late 1700s, when the initial building of the port of Charlestown was underway, plans had already been drawn up for Charles Rashleigh’s grand design. His vision was to have a deep-water harbour encompassing the port we know today, very similar to Mevagissey’s outer harbour – the ‘Pool’. Charles Rashleigh was indeed optimistic and had great entrepreneurial foresight. He knew that a deep-water port located in St Austell Bay close to the local copper, tin mines, and clay pits would be of huge benefit to the economy of his new town. Granite as a building commodity was in abundance and the quarry at Carn Grey was only a couple of miles distant and all downhill to the port. There was, however, a huge economic investment to make, so Rashleigh hoped that his new port would soon be profitable, enough for some reinvestment towards the cost of building his outer deep basin. The huge benefit of a deep-water harbour was clear as daylight for all to see, ships would be able to berth at all states of the tide, and it would also be a secure, safe harbour with an entrance facing west. This would look towards Silver Mines Beach and even in the poorest weather conditions, ships would be able to enter the harbour in relative safety.

A long eastern arm would have been built out from Appletree Point running southwest. This would have given tremendous shelter. Then a short arm would have protruded south from Polmear Island, finishing about 100ft inside of the outer eastern arm. A depth of 15ft to 20ft could have been maintained at low water springs. Larger vessels could have manoeuvred very easily. The short inner dock would then have been given over to shipbuilding and would have included a ship repair facility.

But, and it’s a big ‘but,’ none of this vision would ever come to fruition because of a certain young gentleman called Joseph Dingle. He and his cohort, Joseph Daniel, would eventually be the demise of Mr Rashleigh. He siphoned monies from the Rashleigh empire into his own pocket. Eventually, Rashleigh couldn’t meet his commitments, so the plans were shelved to be hopefully imposed later but it never happened.

There was talk of a renaissance of Rashleigh’s vision during the mid-1800s but the Crowder family couldn’t see the benefits because by then, both Par and Pentewan harbours had been built. It was all too late. Even during the 1930s, plans were drawn up to build a granite breakwater across the bay to give the ports of Charlestown and Par some much-needed shelter. It would have been roughly where today’s mussel farms sit. Again, this never came to pass. So at Charlestown, we are stuck with a port that faces the worst of the winter weather: it was never meant to be.

I wonder if things had been different, if Rashleigh hadn’t gotten into financial difficulties, St Austell would be a completely different place. Par, and indeed Pentewan, wouldn’t have been built. What would the town be like now?

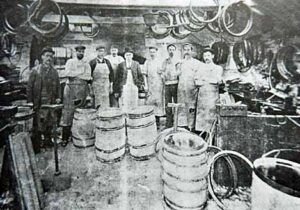

The Coopering Industry

Coopers at an unknown cooperage in St Austell. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Coopers at an unknown cooperage in St Austell. Lyndon Allen Collection.

For many years, barrels (casks) were the main container of choice in the shipping industry. Contents could be stored either wet or dry and once sealed were free from contamination. This was especially so with china clay. During the loading process at Charlestown, the clay would sometimes be contaminated with coal dust on a windy day. The dust would blow from the coal side, across the dock to the clay side. Cooperages sprang up all over St Austell and many made different items, but mostly barrels.

Hogshead barrels were made for the fishing industry. These were designed to leak so that fish arriving at its Mediterranean destination would be a dry product. All the residual oil would have leaked out while in transit. A hogshead could hold 2,500 to 3,000 pilchards. The oil was used for lamps to illuminate the homes of the area. A good wet cooper could on average, make 12 casks a day for which he was paid 5d each. The barrels or casks used by the china clay industry came in two sizes. The 5 cwt barrels (A hundredweight is 112 pounds weight). fetched the same price as the pilchard barrels, 5d each. For the bigger one-ton barrels, the cooper received 7d for each one made.

Baltic schooners at the port would unload staves for the numerous cooperages in the district. These schooners would then be washed out and take clay as a return cargo. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Baltic schooners at the port would unload staves for the numerous cooperages in the district. These schooners would then be washed out and take clay as a return cargo. Lyndon Allen Collection.

During the later years of the 19th century, beautiful wooden schooners from the Baltic states started to bring wood cargo. The timber for the casks, mostly softwoods, was imported in sailing ships, largely from Finland. It came in the form of staves and headings, carried both in the hold and as deck cargo. The only disadvantage was that the wood was very wet and had to be cross-piled in stacks and dried out before use. Otherwise, the casks would not be staunch or leak-proof. Many men were hired as casual labourers to assist with the unloading of staves. Sometimes it would take a week to unload this particular cargo as the staves had to be manhandled, a few pieces at a time.

In the early days, the staves and headings were carried loose which made unloading and transporting a tedious, slow, laborious business (later they were bundled and strapped which sped up the handling process considerably). Discharging these cargoes was all manual work. The staves and headings were passed from hand to hand, from the ship’s hold to dock-side. Then the process was repeated when they were loaded into horse-drawn wagons, and again, once transported to the clay works, the procedure was reversed. There were no grabs, cranes, or conveyors in those days. Only hard work and muscle power were available. However, by 1920, powered conveyors were in use at Charlestown.

Staves were used to construct barrels for various uses including the transportation of china clay, pilchards, and vinegar. It was a seasonal operation because, in the Baltic states, the weather was so bad in the winter months that the seas froze over. This meant there was a sudden dash in the spring and another rush before the autumn, to get everything shipped out. These barrels were made locally at cooperages. In Charlestown, there were originally three cooperages: this dropped to two in 1902. The remaining two cooperages employed 100 persons between them. Rowse’s cooperage was run by Jack and Arthur Rowse and Hannaford’s by Marquis Hannaford.

Alongside the Baltic schooners, were French vessels. A number of these ships came from the French port of Nantes. They brought with them Hazel hoops for the barrel-making process. There were so many French schooners in Charlestown that port signage was also written in French. There were also cooperages at Polgooth, Trewoon, Holmbush, and Mt Charles. By 1908, the trade in coopering slowed and the West of England China Clay Company decided to build their cooperages close to the branch line railway. These were established at Burngullow, Drinnick, and Bugle. This stole trade away from the St Austell coopers. A price war broke out amongst the firms who had all started to undercut each other. This, in turn, stole work away from each other. Finally, to put a stop to this price war, the companies sat around a table and signed an agreement that no one cooperage would undercut another in the future. A set price per cask was agreed.

Staves were cross-piled and allowed to dry. This photo was taken at Charlestown at Rowse’s Cooperage and was on the site of the new detached homes of Cooperage Close, which is behind Atishoo Gallery. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Staves were cross-piled and allowed to dry. This photo was taken at Charlestown at Rowse’s Cooperage and was on the site of the new detached homes of Cooperage Close, which is behind Atishoo Gallery. Lyndon Allen Collection.

The dimensions of the timber varied according to the size of the cask being made. Each cask consisted of staves, headings (top and bottom), wooden trusses, and iron hoops. These Iron hoops replaced the earlier hazel hoops. The cooper manually ‘humped’ into the cooperage, sufficient material for a cask – if he was lucky, he might find a wheelbarrow. He then jointed each stave using the jointer.

However, the trade was in steady decline and by the beginning of the First World War, it had practically finished. The shipment of wooden staves from the Baltic countries became the target of the German submarines. A Charlestown sea captain, Alphonso Hurley, was attacked by U-32 (Capitaine Max Viebeg) south of Start Point. Alphonso was on his way back to Charlestown with a cargo of staves aboard. His sailing ship, the ‘Edyminion,’ was sunk by gunfire with the loss of everyone on board. Those who lost their lives included Edward James Barron and Timothy O Leary both from Eastbourne Road, St Austell. Alphonso was lost at sea but his wife Rose is buried at Campdown Cemetery and a memorial to him is on her headstone. His name also appears on the village war memorial and the Tower Hill Memorial.

During those dark years, the industry all but closed and it would never pick up again, the halcyon days were over. Rowse’s struggled on until the outbreak of the Second World War but with a reduced staff, it finally closed in 1940. Higman’s had already closed, nearly half a century earlier, in 1896, but Hannaford’s continued making barrels for St Austell Brewery right up until the advent of steel beer barrels in 1950. Sadly, coopering is a trade now consigned to the history books. As with most things connected with the china clay industry, it was a huge employer in its glory days. The area prospered from its existence which employed over 1,000 men and added to the prosperity of the area.

Many of the deep-draught foreign vessels took so long to unload that they became victims of a falling spring tide. Their departure would then be delayed around ten days until the tide started to build up to a spring tide again. This was costly, and ships’ masters would have to pay port charges for taking up dockside space. A few people benefitted from this however, like the landlord of the Rashleigh or Hodge the butcher.

I read a book recently about a journey through Cornwall, published in 1914, where the author described the scene at Charlestown.

“The dusty road leads through Holmbush, a suburb of Charlestown, which took its name from the wayside ‘Holly Bush’ Inn. Charlestown itself is more curious than beautiful. It is, in fact, the port of St. Austell, of which it is really an extension, and was formerly called Polmear. Charlestown is a place with one small, but very busy and crowded dock, and the dock and the quays, and all the roads into and out of the place are a study in black and white, and barrels. The stranger to Cornwall, proceeding westward for the first time, is apt to be puzzled by these strange evidences. He has come across the first signs of the great and prosperous Cornish china-clay industry. The whiteness of everything that is not black is caused by the leakage of the china clay, and the blackness of everything that is not white is the result of coal dust. The mountains of clean new barrels, just fresh from the cooper, are for packing the clay for export. Charlestown also does an import trade in coal, hence the alternative to Charlestown’s sanctified whiteness, but when it rains, as it not infrequently does in Cornwall, the result here is a grey and greasy misery, compact of these two substances.”

The demand for china clay

Around the late 1870s, the mining industry in Cornwall collapsed, this was due to copper and tin being found in places like Vietnam. At Charlestown, the port’s management team looked for other revenue streams to provide income and employment. China clay and china stone rapidly became the replacement cargo. Up until that point, I think it can be safely said that the way to St Austell from Charlestown was just a rough cart track. Copper and tin ore had been the mainstay of the port for 90 years since it evolved from the hamlet of Polmear. With a marked shift to china clay and china stone, the road was widened due to the amount of traffic on it. It soon became known as ‘The Great Charlestown Road’ and was the widest approach to any port in Cornwall. It was given other, less flattering names as well, like the ‘rutted lane’ and the ‘ploughed field’.

The clay industry required a constant stream of horse-drawn wagons from the pit to the port. The clay came in wooden carts containing three tons of dried clay. With an average of 90 tons of cargo per vessel, it required 30 wagons of clay to fill the vessel and of course, this meant that in addition to the carts, over 90 horses to pull the wagons. This new, replacement trade would ship on average, 15,000 wagonloads of clay annually. So 45,000 to 60,000 horse journeys from the pits to the port! This heralded the boom years for the port. Massive amounts of china clay were exported to the markets on the continent. Tremendous volumes of coal were imported for the drying process and added to this, were imports of timber, fertilizer, and cement.

During the early 1900s, due to the depth of wheel ruts caused by the wagons, a steam roller was employed daily to roll hardcore into the furrows. Constant attention was required to address the running repairs to Charlestown Hill in particular. Wheel ruts were a major issue and the hardcore was brought from the pits to fill the ruts. A steam roller then ran the length of the hill compacting the infill. This resulted in the height of the road increasing. It is very noticeable today if one looks at the western side of that road.

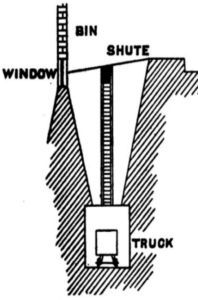

A diagram of the rail system and the storage bins at Charlestown Dry.

A diagram of the rail system and the storage bins at Charlestown Dry.

This was however, exacerbated by the addition of tarmacadam just after the First World War. Also, at the same time, the wheelwrights were instructed to widen the wheels of the wagons to try to reduce damage to the road but this was to no avail. In 1905 the management of the clay companies now looked at alternatives for clay transportation to Charlestown. They put their heads together and came up with a plan to pipe clay slurry from a clay pit at Carbean, Stenalees, to a new purpose-built drying shed at Charlestown.

The village’s first purpose-built clay drying facility was built on the foundry site and opened in 1906, it was called ‘Carbean’ dry, after the pit at Stenalees. This was so successful that just two years later, ‘Carclaze’ dry opened up in the lower portion of the village, just to the northeast of the dock itself. Carclaze drier could produce four tons of dried clay per hour. Clay here was transported from the drier through a system of tunnels by wooden carts. A 12-inch diameter steel pipe came down through the fields and over the stone wall to the rear of the settling tanks. There were eight of these in number. Slurried clay was allowed to flow from Carclaze to the Charlestown settling tanks. Once the clay had settled, the water was drained off and it was then spread on the drying floor via the travelling bridge that ran on rails located on each side of the floor.

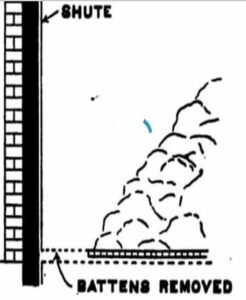

The storage bin floor with its removable battens.

The storage bin floor with its removable battens.

The drying shed was 380ft (feet) long with a floor capacity of 1,000 tons of clay. The eight large slurry tanks behind held another 8,000 tons of slurried clay. In its construction, over 12,000 tons of stone, 3,000 tons of sand, and 300 tons of cement were used. This was all covered over with pitch pine roof trusses and roofed with asbestos sheets. A chimney flue built of stone and brick 120ft high was attached at the northern end. It was fired by a furnace at its southern extremity, hot air being circulated below a porous stone floor. The clay was poured over the floor from the settling tanks outside to a depth of six inches. The water then seeped down through a floor a foot or so above the ground. The ashes from the furnace were taken down the hill in carts, hence the name ‘Ash Hill’. The dry opened for business at Whitsun in 1908 although it was not officially opened until January of the following year.

The coal-fired furnace was located at the seaward end of the building and hot air was pumped using bellows under a gap or void below the floor. The hot air dried the clay above and when dry it was despatched to the storage bins. The men working on the floor here, and in many other dryers, wore Dutch wooden clogs as this protected their feet from the hot floor. Rubber soles melted. The clogs came from Dutch shipping visiting the local ports to pick up china clay.

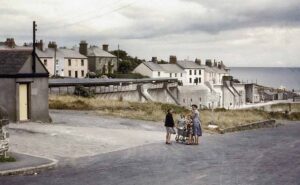

The gantry can be seen running along the top of the dock. Further down Quay Road, the shutes had hoppers attached to tip the clay into. The gantry was removed in 1968. The old cask banks can be seen behind the family pictured and the building to the left with the yellow door was a weighbridge.

The gantry can be seen running along the top of the dock. Further down Quay Road, the shutes had hoppers attached to tip the clay into. The gantry was removed in 1968. The old cask banks can be seen behind the family pictured and the building to the left with the yellow door was a weighbridge.

It was a very elaborate type of clay drying and storage facility where the contours of the specifically chosen site permitted deep storage bins to be excavated alongside the drying floor. Adjoining the drying floor, in place of the usual simple drop to the linhay floor, was a series of deep conical bins: these were excavated out of the solid rock and lined with masonry. Each conical bin measured 62ft long by 30ft wide by 30ft deep. Each had a vertical steel ladder attached to the drying floor wall 10 feet away from the dividing wall that held the loading shute. The two bins at each end had a series of stone steps built into the bin masonry which protruded like stepping stones. The steps were similar to those used in the recent production of ‘The Phantom of the Opera’. At one end of each bin was a vertical wooden shute which was designed with removable battens down the front: these wooden battens were two feet long and 8” x 3” in size. There was also a channel along the floor which was similarly provided with battens. These so-called ‘battens’ were four feet long of 6” x 3” timber. Beneath the entire length of the floor of the bins ran a tunnel along which wooden trucks were run on steel rails. When a bin was ready to be filled, all the battens were in place. The process of emptying was then commenced at the shute end, and the clay was shovelled down the shute directly into the waiting trucks below, the battens being removed as the level of the clay was lowered. When the bottom of the bin was reached, the floor battens were then removed one by one, beginning at the end nearest the shute, until the whole bin was empty. The trucks conveyed the clay out of the tunnel and along an elevated tramway called the ‘Gantry’ and it was then tipped directly down shutes into vessels berthed on the quayside. These tunnels had passing bays so trucks could pass each other and there was also a weighbridge inside, located down the far end, towards the dock. The whole system of tunnels was lit by carbide lights which gave off a horrible odour. During the early 1950s a press shed was added. This was more efficient and the number of setting tanks was then reduced to four. A crib hut and toilet block were also added at that time. The press shed blew down in a south easterly violent storm in the winter of 1983/4, the same storm that demolished the end of the pier.

Wartime

During the Autumn of 1940, a local boat builder from Looe called Frank Curtis, won a contract with the admiralty to build and fit out wooden minesweepers.

Frank Curtis had been a successful boat builder, building many fishing vessels from his yard at Polean, Looe. During the war years this yard was turned over to building vessels for the admiralty.

In the summer of 1940, Frank signed an initial contract to build thirty-five wooden minesweepers at Par. They were of wooden construction to combat the threat of magnetic mines and in two sizes – 140ft and 96ft. These became known as MMS Short and MMS Long (MMS was the acronym used for motor mine sweepers). There were also sweepers built, known as Trawler Minesweepers. A faster sleeker model was made by Fairmile in Hampshire. These were built at their factory in kit form. The kit was packed into six wooden crates designed to fit neatly onto the back of a standard 15-ton Army-issue lorry.

Locally, Frank Curtis chose Par harbour as his build site and Charlestown for the final fitting out of the vessels. Wood was sourced from local farmers’ fields and brought to Par on lorries. The wood was then cut to dimensions by a purpose-built sawmill located next to the shipyard on the dockside. The build sites were on the end of the east quay. There was enough room for five vessels to be built side by side, a total of two sites at Par. Purpose-built slipways were constructed of steel and wood, directly astern of the newly built hulls. After the war, these slipways were concreted over in pairs and can still be seen today, protruding across the beach from the eastern pier. The Par harbour clay facilities were painted in camouflage colours.

The dock gates in 1942, you can see the anti-tank ‘Dragons Teeth’ concrete pimples on each side of the dock gates. Lyndon Allen Collection.

The dock gates in 1942, you can see the anti-tank ‘Dragons Teeth’ concrete pimples on each side of the dock gates. Lyndon Allen Collection.

These wooden hulls, once completed, were launched down the slipways and towed around the bay to Charlestown Dock for the next stage, the final fitting out. Adding engines, wheelhouses, sweeping gear, and armaments was all part of the final fitting out at the dock.

Between the two shipyards, over one thousand personnel were employed. Shipwrights came from all over Cornwall and many found lodgings with village families just as the evacuees had done a couple of years before. Mr Pengelly from Looe became the Charlestown yard foreman and he lived at the time in ‘Ardenconnel’. Senior shipwright Mr Alf Rowe came from Percy Mitchell’s yard at Portmellon to manage the team of shipwrights at Charlestown. During the war years 1939-1945, a total of 402 wooden minesweepers were built for the Royal Navy.

At Charlestown, a block barge had been placed across the harbour entrance by the Home Guard. This would be pulled aside for ship movements in and out but in the case of an invasion, orders were given to sink it in situ, thus creating a barrier. Concrete and tubular steel tank traps were also placed on the beaches, and eight ‘Dragons Teeth’ tank traps were positioned ten feet to the west of the dock gate and three more, ten feet to the east of it. Two concrete type 26 pillboxes were installed overlooking the harbour, one to the east in the Cliff Park field, and one to the west, opposite the southern end of Battery Terrace.

On the western dockside at Charlestown, a large travelling crane that ran on rails was erected. It weighed upwards of 60 tons and could lift 30 tons. Ironically, this was the location of the area of the dock wall that collapsed during the gate widening of 1971. The excessive weight caused underlying issues. A machine shop was also built outside of the Pier House but on the dockside. Storage sheds were built at the top area beside the jetty. A 15ft high wall of corrugated steel sheets was erected all around the dock so the public couldn’t peer in. Again, this was all painted in camouflage colours.

Village girl Leonie Edwards was one of the Charlestown girls employed at the shipyard at Par. A bus would pick them up at the corner of Church Lane at 7 am. On Sunday there was no bus service and they either had to walk or cycle to Par. Leonie did many jobs at the shipyard like painting or rolling oakum for caulking. They wore dungarees whatever the weather, and a gas mask was carried at all times. When the war finally ended, a few years later, Frank Curtis still had half a dozen vessels left that had not been built. He decided to honour his contract and these were built, fitted out, and eventually sold to the fishing industry. Frank Curtis also built motor torpedo boats at Looe. Minesweepers were also fitted out in Looe, and there was another yard at Totnes, Devon.

The drier closed its doors in 1970 although the gantry had been demolished in 1968. For the last two years, clay was dried and loaded to lorries either for tipping at the now modern shutes which had hoppers attached, or driven to Par for loading there.

Now things rapidly changed, the gantry was demolished and the three remaining shutes had hoppers attached to them. One more shute was constructed outside of number 14 Quay Road and a long steady ramp ran up to it, parallel to the dockside. Lorries weighed on the weighbridge and reversed up the ramp to tip. There, a man would knock out the pin to the tailgate and the lorry tipped its contents into the hopper. This flowed down the shute and into the holds of the waiting vessels.

Charlestown dock at its peak, berthed three abreast is a mix of sail, steam, and motor vessels. Lyndon Allen Collection.

Charlestown dock at its peak, berthed three abreast is a mix of sail, steam, and motor vessels. Lyndon Allen Collection.

I remember one evening when I lived at Quay Road, I went to the Rashleigh Arms for a drink and as I left at closing time, I noticed a very drunk Philippino sailor in front of me. His ship was berthed at the clay side under the north shute. The hopper was left open (this was unusual) and he was in front of me about 15 yards ahead. When he was opposite the shute he turned, ran towards it and threw himself into the hopper. A few seconds later I heard a bang and saw a cloud of dust. That was him hitting the ceiling (that’s the floor of the hold of the ship). How he never died I will never know.

In the late 1980s we lived at number 9 Quay Road, the lorry driver would be looking in the bedroom window as he started to reverse to tip. He would have been as close as five feet away.

As time passed and ships got ever bigger, during the 1960s, plans were afoot to possibly widen the dock entrance to allow larger vessels into the dock. When my grandfather was harbour master, he suggested that the gates should be widened. After much planning and many feasibility studies, Charlestown Estate Ltd decided to go ahead with the plan and work was finally undertaken in the spring of 1971. A new electric gate was designed and built by Visick Ltd at Devoran. This single gate would replace the existing pair of wooden gates that had been traditionally used. It would be hinged at the bottom and would fall backward into a sump on the dock floor. It was said to be ‘state of the art’ at the time of design. One drawback, however, was that in 18-20 years it would be rusted and would have to be replaced. Bids were tendered for the work and local civil engineering firm E. Thomas and Co. were the winning contractors.

The scheduled works were to take eight weeks to complete. However, with the dock empty of water for a month, a portion of the western dock wall collapsed. This put another three months of build time onto an already busy schedule. The dock entrance was widened by 8ft at that time from 27ft to 35 feet. It was a large engineering project. The western side of the dock had to be removed back far enough to receive a new precast concrete block wall. These blocks measured 5ft x 2.5ft x 2.5ft. They were stacked up in front of the Pier House and placed in situ by a crane as needed. Originally, the gate had steel railings on top of the walkway and at each end, a semi-circular bar to make cyclists get off and navigate this obstacle. This meant they couldn’t approach and go over the gate at speed. A new sluice chamber and steel door were also constructed to the west of the gate using one of the original dock gate sluice winders. The gate was designed to fit into a sump on the dock floor and lie flush with it for vessels to pass over. As the gate was lowered it let air out and water in. By the time it took to get to the bottom (four minutes), it weighed 32 tons. As it was winched back up using an electric motor and cable, the water is replaced by air making it lighter.

However, problems soon appeared and all involved realized the new gate had major design flaws. The initial problems were the holes to let water in and air out were not large enough. Over time the sump filled with debris, i.e. sand, mud, stones, and seaweed. This created problems as the gate would not then sit flush to the bottom. Ships would then strike the gate around the area of the walkway and on several occasions, the gate railings were buckled beyond use. Hence the rope guard system today. Another problem was opening the gate after a heavy swell. Undertow or undercurrent would throw the gate upright after it had submerged. The gate would be upright with all the wires slack and then it would rapidly fall backward putting a huge stress on the system.

You can see from this photo the damage caused by the consequence of the dock being dry for so long. This damage added many months of extra work to the project. Lyndon Allen collection.

You can see from this photo the damage caused by the consequence of the dock being dry for so long. This damage added many months of extra work to the project. Lyndon Allen collection.

I witnessed this many times over the years but on one occasion the wires parted and the gate sank out of sight. I wrote about it in my first Charlestown book Time and Tide. Over time, with wear and tear, another issue came to light. Ships propellers would scatter the guard plates for the gate hinge that ran the full 35 feet width. A diver would then have to go down and put them back after the gate was closed, or else the gate would leak badly. This happened at every gate opening, day and night. In 1990, during ongoing repairs to replace the rubber gate seals, it was found that the concrete block walls had concrete cancer. Bear in mind that was 34 years ago (written in 2024). Also, the gate storm latches were not fit for purpose due to this, hence all the wires and ropes up to the quay, resembling at times, a spider’s web!

As the dock was dry for so long, a portion of the western side of the dock wall fell away. This put months on the job. This collapse took place in the same area as the huge dockyard crane was situated during the war. It was 60 tons in weight and ran on rails. I think the four or five years it ran up and down the dockside had created significant subsidence below the granite but it took an empty dock for it to completely collapse. The repairs were completed through the summer months and the new electric gate was fitted. It opened for the first time on the 5th of September 1971 – on regatta day. You can read a full account of all of the story of the dock gates and much more in both of my Charlestown books.

This gate widening raised the cargo weight from 400 tons to 800 tons. The port then enjoyed somewhat of a renaissance for the next ten years or so. But the hands of time turned slowly, slower than the design of new vessels. They rapidly became ever larger. By the mid-1980s, realization that the port was again struggling with size dawned on all concerned, especially the port owners, the Crowder family. When Lady Florence Crowder died, her son Petre Crowder decided to put the port up for sale. It was the end of the commercial port as we knew it. Within a decade, all commercial traffic had more or less ceased. During that last decade, there had been quite a change in port owners: BOM Holdings which was run by David Bulstrode who was director of QPR Association Football Club at the time, Target Holdings owned by Peter Clapperton, and eventually the Square Sail Shipyard Ltd.

During the summer of 1993, Disney Studios came to Charlestown to film a new production of The Three Musketeers. This was a high-budget film with a stellar cast of some of Hollywood’s A-listers including Charlie Sheen, Kieffer Sutherland, Rebecca De Mornay, and Oliver Platt. Scenes were to be filmed at night. Disney hired a tall ship from Bristol called the ‘Kaskelot’ which was owned by the Square Sail Shipyard Ltd. What most people didn’t realize at that time was that Square Sail was looking for a new home: they had been given their marching orders by Bristol City Council. They didn’t know the port of Charlestown was up for sale until they arrived. Company director Robin Davies quickly made a deal and purchased the port. The company would soon move lock stock and barrel to Charlestown. This ushered in a new era for the port, filmmaking. The company moved to the village the following spring of 1994. They almost immediately started to film TV productions which ran alongside the traditional clay, coal, and fertilizer shipments. This meant that filming and commercial trade interfered with each other. Filming required no noise and the loading and unloading of ships was a very noisy procedure so a compromise had to be met. In the end, the number of clay ships reduced and filming slowly took over as a commercially viable solution to income. The port pilot, Mr Graham Brabyn, had to adjust his pilotage for these vessels. That’s because they carried more windage due to the tall masts. Graham had previous experience with tall ships with the ‘Marques’ and ‘Ciudad De Inca’ in the early 1980s and soon got used to the daily comings and goings during filming. He used to say to me. “Take off the masts and it’s just a small barge,” which is very true but it’s just that with so much top hamper they caught the wind.

Slowly, as time moved on, clay cargoes became less and less. There were a few new experimental cargoes like grain and sand (the sand was being shipped to Guernsey on a trial basis). Sadly, after a handful of cargoes, it all fell through. The glorious days of sail, steam, and the diesel engine had come to a grinding halt. On the 13th of December 1999, the last cargo was taken by the ‘Ellen-W’. Two hundred years of commercial shipping had stopped. The village would never be the same again, a way of life that had evolved for generations suddenly was no more. The filming also came to an end. In my opinion this was partially put down to greed, cutting off their nose to spite their face. The owners charged too much money thinking that the film work would always be there. They thought, that once they had filmed a scene in a series, they would always need to use it. The TV and film companies got wise to it. So they priced themselves out of the market. However, a controversial new business enterprise replaced it, the pop-up restaurants that line the harbour. Love them or hate them, I feel they are here to stay. What the future holds for the port, no one can say, but I would hate for it to end up like Pentewan, Lamorna or St Agnes. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to Charlestown Estate Ltd as caretakers. They kept it safe from overdevelopment whilst they were custodians of the village. More change has come about in the last 40 years than the 190 years before that. For us, the original families, it has been a bitter pill to swallow. I, like many, feel that we once had a silk purse and now we have a pig’s ear! Whatever the future holds, I sincerely hope that its prospective owners treat the port with the historical respect and care that it deserves and do not try to sell its soul for a quick profit.

Endnotes:

- Charles Rashleigh (died 1823) was an entrepreneur who developed Charlestown as a port, named Charlestown after him.

- John Smeaton (1724 – 1792) was an English civil engineer responsible for the design of bridges, canals, harbours and lighthouses.

- A Pilchard Seine is a group of fisherman who fish using seine nets – large nets with sinkers on one edge and floats on the other that hangs vertically in the water.

- A ropewalk is a long straight narrow lane where long strands of material are laid before being twisted into a rope.

- A fish cellar was where fish was processed and packed in layers of salt.

- A lime kiln is used for the calcination of limestone to produce quicklime (calcium oxide).

- Since 1824 a bushel has been defined as eight imperial gallons, or 2,219.36 cubic inches (36,375.31 cubic cm).

- A graving dock is an enclosed basin into which a ship is taken for underwater cleaning or repair. It is an obsolete nautical term for scraping, cleaning, painting, or tarring of a boat.

- The Duporth Cup is a ceramic item with great significance to the history of Charlestown Port.

- Ore ‘hutches’ or ‘Platts’ are visible on the first photograph of the harbour in this article.

- A warp or hobbler as it was also known, was a hawser used to steer or guide a vessel during manoeuvres in and out of port in the days of sail.

Lyndon Allen

Lyndon Allen

Lyndon Allen grew up in Charlestown, St Austell. He comes from two longstanding historical families in Charlestown, who have been an integral part of village life for over 230 years, particularly in its maritime heritage. Lyndon attended both Charlestown and Penrice schools before leaving in 1981. He pursued a career in the commercial fishing industry, working from the port of Charlestown for thirty-six years, in line with his family’s strong connection to the sea. He retired from the fishing industry in 2019.

Currently, Lyndon operates the award-winning Charlestown Walking Tours, a business he established after the lockdown. He is also an author, a passionate historian, and manages eleven Facebook historygroups, including the popular St Austell History Group. Lyndon has authored four comprehensive history books: two on Charlestown’s history, one on St Austell’s history, and a maritime history book about the St Austell and Mevagissey Bays.

His books are available for purchase on his website at www.charlestowntours.co.uk

A cracking and very informative account of Charlestown from someone who knows it first-hand! Thank you Lyndon for sharing your knowledge with us.

Thank you Nick for your very kind words.

Kind regards Lyndon.