Someone once said, “If we believe that tomorrow will be better, we can bear a hardship today.” Honestly, I don’t think we, as a society, know what hardship is. When I was a child we had little money, even though both my parents worked and had relatively good jobs. My father was an alcoholic and spent all his money, and I will add everyone else’s, on feeding his addiction.

The horrible truth is, that since rationing ended in the mid-1950s, I don’t think many people have truthfully known what it is to struggle or to starve. Today, as a society, very few of us go ‘without’ like our forebears did. Yes, the cost-of-living crisis affects us all, but just pause to think a moment. If we go back a few generations and we are in a society with no credit. If you didn’t have the money to pay for something right there then you went without. It was as simple as that.

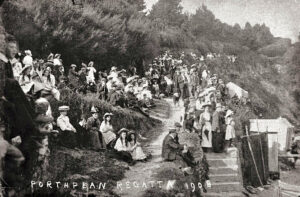

Porthpean regatta 1908. In times of great hardship, days out, whether it be a tea treat or a visit to a fete or regatta, were always looked forward to with great anticipation. (Lyndon Allen Collection)

Porthpean regatta 1908. In times of great hardship, days out, whether it be a tea treat or a visit to a fete or regatta, were always looked forward to with great anticipation. (Lyndon Allen Collection)

For all of us today, food is easy to come by. We can just roll up in our flashy car at the supermarket and buy what we like. Foods from all over the world are there, laid out before our eyes and for our convenience. Two hundred years ago, there was no such thing as a supermarket, and very few shops for that matter. We did though have a fabulous Market House In the town. Our ancestors either had to grow it or make it themselves, items like butter, cream, and cheese took a long time to prepare. Everything vegetable-wise was grown on your own plot, planted in spring, and harvested in September. It was then stored for use throughout the harshest winter months. Jams were preserved and other things were pickled and stored away. If you had a few fowls, you could swap eggs with neighbours for other items like fish for instance, this would be especially so to those who were lucky enough to live along the coast. The St Austell old Market House used to stand near the western entrance to the town church. It was once described as “a considerable market wherein all sold commodities were necessary for the life of man.” The basement of the building was the butchers’ market, the first floor was for potatoes, and the upper story was the corn market. The boot and shoe market was held along the north side of Fore Street as far as Biddick’s Court, the fish market was on the south side as far as Vicarage Hill and the vegetable market was held on Church Street. There were no pavements in the streets at that time. The old Market House was demolished in the year 1844.

During a conversation with a local lady called Judy Merrit, she told me that she had been born in the St Austell Union Workhouse. Her mother lived there for twenty years. This photo was taken in the back of St Austell’s workhouse, the nursery. The photo courtesy of Judy who is the one with a cross on her bonnet.

During a conversation with a local lady called Judy Merrit, she told me that she had been born in the St Austell Union Workhouse. Her mother lived there for twenty years. This photo was taken in the back of St Austell’s workhouse, the nursery. The photo courtesy of Judy who is the one with a cross on her bonnet.

Work was a lot harder and much more physical. Those employed in the china clay pits and underground down the mines were digging and shovelling all day with little nourishment to sustain them. Many people spent long hours underground working in the mining industry. The poor air quality and inadequate diet took its toll on many. It can be said in St Austell a tenth of the population in the early 19th century worked this way. At Charlestown, Pentewan, and Par, the dock porters lifted two hundred-weight casks of clay all day long. Bags of clay weighed three hundred-weight. I recently found a reference to this in a book from 1820. Today, not one single person works underground! In fact, life was so hard for many that they decided to sell up and emigrate in search of a better life. In 1818, the West Briton newspaper published that fifty persons including “infants at the breast” had left the port on a ship called the ‘Charlestown.’ Captain Williams was her master. She was only a little vessel about 80 feet long and had been built in Charlestown. Despite much research, I have found no records of a ship called ‘Charlestown’ in the American immigration lists. It is possible she sailed to Ireland, thus completing the first leg of the journey. The passengers then changed to a much larger vessel for the onward journey across the Atlantic.

Many people worked at sea, either on merchant vessels or in the fishing industry. These jobs were fraught with danger, both then and now. The advent of the steam engine made life easier for the crews. Farming was also another hard job with a lack of mechanical implements. Another major source of employment was Lime burning in many local villages, the life expectancy of a limekiln worker was just 30 years.

Religion also played its part. Pray for a better life and your prayers will be answered. It was said that during the last 250 years, some of the rougher villages especially around the copper and tin mining areas were similar to the Wild West towns of the American West.

Charles and John Wesley’s arrival in Cornwall in 1743 certainly changed the religious and physical landscape of the Duchy. Wesley thought that there were sinners who needed to repent. The sinners needed to take Jesus into their hearts. Wesley preached in St Austell on twelve separate occasions. At the peak of the Methodist movement, there were over 600 Methodist chapels in Cornwall, many of which were built in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Wesley’s message was readily accepted by the Cornish. This was especially so in St Austell. By 1750, for example, thirty of the mining communities in the west of Cornwall had Methodist Societies. By 1798 Redruth and St Austell contained over 5 percent of the whole country’s Methodists.

Pauperism was rife, many people, old, young, infirm, single mothers, the elderly, and people with disabilities ended up in the Workhouse. Many were forced to share beds. The system eroded all dignity. The inmates were awakened to the sound of the workhouse bell. All meals were summoned by the bell. Conditions were atrocious, to say the least, you had to work hard to be able to earn your keep, in other words, your bed and food. Today the St Austell workhouse bell is situated in the town museum at the Market House. If you haven’t visited, please go along and pay a visit, the volunteers there do a fantastic job.

Charlestown Wesleyan Chapel taken in the late 1800s. This chapel is one of the older Wesleyan chapels in the old parish of St Austell. In times of hardship, prayers were offered but unfortunately, few were answered. John Wesley preached in St Austell no less than twelve times. (Lyndon Allen Collection)

Charlestown Wesleyan Chapel taken in the late 1800s. This chapel is one of the older Wesleyan chapels in the old parish of St Austell. In times of hardship, prayers were offered but unfortunately, few were answered. John Wesley preached in St Austell no less than twelve times. (Lyndon Allen Collection)

An era devoid of mechanical aids also added to the everyday misery. There was no mains electricity. Cars didn’t exist then either. If you were fortunate, you may have owned a horse or mule and maybe even a trap to get around. My ancestors came from Veryan. They came to Polmear (now Charlestown) to build the port, my great aunty Heather told me her grandmother (my great, great grandmother) Eliza Beynon had told her that the family would get up early and walk back to Veryan to visit their family, have a celebratory dinner, and walk back to Charlestown with no light of any description to guide them through the darkness.

No washing machines meant clothes had to be washed by hand, wrung out with a mangle, and dried outside all year round. This was usually done once a week on ‘washday,’ normally a Monday. Wash houses were usually found in the garden along with the house toilet closet. Fridges and freezers were also non-existent. Keeping food fresh was difficult. This is why so many recipes were created to use up leftovers. Tea treats evolved and this happened a few times a year, usually at a Methodist chapel outing or a Band of Hope gathering. The occasion was, as the word suggests a real ‘treat.’ Today we can treat ourselves every day if we so wish.

I have always said that I don’t envy a woman’s life. All the stress of childbirth and other feminine issues. But just stop and think for a minute, what that must have been like even a brief time ago. In say, the Victorian era, no pain relief during childbirth. So many families were so used to ‘loss.’ Death during childbirth was a common occurrence for both mother and child. No contraception meant for an unsettled and anxious life. Factor in infection and disease and you have a perfect storm of misery. To all young mothers reading this, can you imagine a life without a disposable nappy? Conditions were so hard for them. Large families were often crammed into small spaces. No mains running water also added to the immeasurable suffering. Even as recently as 1910, there were significant deaths from Cholera in the St Austell area. Mt Charles, Charlestown, and Mevagissey were villages recorded as having a high number of deaths.

Society in general was more musically educated. Long before the television set and wireless found their way into people’s homes, people had to make their own entertainment. My great-grandparents had six children, five of them could play the piano beautifully. Families would gather around the piano and sing. Theatre visits were commonplace and I will add, a cheap form of entertainment.

Moving forward a little more to the Great War, we then see so much hardship brought about by the tremendous loss of life. The trauma, experienced by families is now impossible for us to comprehend.

The great depression of the 1930s though, would give way to an era of prosperity with the arrival of mass tourism to the area. However, it was to be short-lived. War would again darken our doorstep in 1939. Rationing was introduced, and I talk about this in detail in my St Austell book – The Porcelain Parish. There is a whole chapter on the war years.

So if you add all these things together, and ask yourself the question “Do we know what hardship is?” In honesty, the answer is, no we don’t.

I try to remember something positive that was said to me many years ago: “Every day may not be good, but there’s something good in every day.” Maybe our ancestors knew this. Lessons learned and passed down that would inevitably lead to a more privileged society than that of our ancestors and their ‘hard-knock life.’

Lyndon Allen

Lyndon Allen

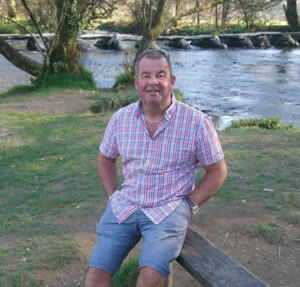

Lyndon Allen grew up in Charlestown, St Austell. He comes from two longstanding historical families in Charlestown, who have been an integral part of village life for over 230 years, particularly in its maritime heritage. Lyndon attended both Charlestown and Penrice schools before leaving in 1981. He pursued a career in the commercial fishing industry, working from the port of Charlestown for thirty-six years, in line with his family’s strong connection to the sea. He retired from the fishing industry in 2019.

Currently, Lyndon operates the award-winning Charlestown Walking Tours, a business he established after the lockdown. He is also an author, a passionate historian, and manages eleven Facebook historygroups, including the popular St Austell History Group. Lyndon has authored four comprehensive history books: two on Charlestown’s history, one on St Austell’s history, and a maritime history book about the St Austell and Mevagissey Bays.

His books are available for purchase on his website at www.charlestowntours.co.uk