Lamorna Spry brings us a fascinating piece of Cornish History brought to life through verbatim quotes by members of her family.

On Monday 18 May 1896, in scenes reminiscent of the Boston Tea Party, local Cornish fishermen from Newlyn and Mousehole boarded around 15 of the boats from the Lowestoft and East Country fleet and threw their catch of mackerel into the sea. Contemporary newspaper reports speak of up to 100,000 mackerel being thrown overboard. Before very long, fishermen from Porthleven and St Ives joined in the protests that were only quelled with the arrival of several hundred troops of the Royal Berkshire Regiment supported by three Royal Navy gunboats. As staunch Methodist Chapel-goers, the Cornish fishermen were ‘Sunday Keepers’ who believed it a sin to fish or land fish on the Sabbath. This was typical of fishing communities not just in Cornwall, but also Ireland and the west coast of Scotland. The Lowestoft men, locally referred to as ‘Yorkies’, had no such scruples and with a large fleet of company-owned drifters, landed fish both on Saturday and Sunday, and were about to land considerable catches of mackerel to be sold in the market on the Monday. The glut of fish would have lowered the price of mackerel and made it hard for local fishermen to sell their catches during the rest of the week. Prices could fluctuate enormously, and in early April 1896, prices of 18 shillings for 120 mackerel were recorded, but days before the riot, they were fetching a mere three shillings. The mackerel season was also very short, generally only lasting a maximum of three months and therefore every catch was critical for the support of families throughout the rest of the year.

Digging through boxes of family possessions, I came across a first hand account of the riots of 1896, recorded in about 1970 when my great aunt was 90 years old. Despite being relatively brief, further research of local archives and newspapers has enabled me to piece together an intriguing account of community history within a small Cornish fishing port struggling against powerful religious, economic and social influences.

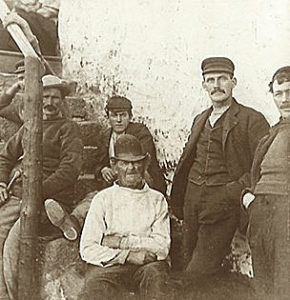

Newlyn Fishermen circa 1896 (I believe the second from the right is my great grandfather Richard Nicholls)

Newlyn Fishermen circa 1896 (I believe the second from the right is my great grandfather Richard Nicholls)

My great-aunt was Eliza Jane REYNOLDS (nee GUY) and in later years she lived at 7 Florence Place, Newlyn but the 1891 census shows that around the time of the riots, she was 14 years old and living with her siblings and parents at 12 Chapel Street, just above Newlyn harbour. Her father was James GUY who owned the boot and shoemaker’s shop in Duke Street (now a car park) but was also the owner of a ‘lugger’ rigged boat PZ404, named the ‘Pride of the Sea’ and nicknamed the ‘Longnose’. The boat was skippered by Francis RICHARDS and newspaper reports of the time contain several references to the boat, including the capture of a 10-foot shark off the Eddystone lighthouse, weighing a quarter of a ton. Being so intimately involved in the fishing industry, the family’s fortunes were very much dependent on the price of fish and being Methodists, would have had every sympathy with the actions of the local fishermen.

Painting of PZ404 by James Guy of his boat the ‘Pride of the Sea’ nicknamed the Longnose

Painting of PZ404 by James Guy of his boat the ‘Pride of the Sea’ nicknamed the Longnose

Eliza says in her account of the riots ‘ …years ago we used to have a big fleet here of Lowestoft boats, come catch the mackerel and they were a very rough lot of men, a very rough lot of men, drinking when they were ashore, always in public houses and drinkin’ – a dirty lot of men. Well it’s true – we wouldn’t go out of a night if the boats were in for the world. We wouldn’t go down long – ‘fraid. Well any’ow our men, our fishermen, were a good livin’ lot of men and they honoured the Sabbath. Well now it come on so bad that these men used to go to sea Friday night and Saturday night you see and Sunday when ours never used to go. Well Monday mornings they would bring their fish to market and they would have the best price for all their fish. When our men would go the Monday come in the Tuesday morning and they couldn’ sell them. Sometimes ‘ad to throw them away – we couldn’t get a livin’ our men.’

Eliza Jane aged 90

Eliza Jane aged 90

Thus, the commonly held view is that the riots were purely the result of religious practices and their economic consequences, but Eliza also pointed to another social factor, namely the intense rivalry between the poorer Newlyn community and its economically vibrant neighbour, Penzance. She explains:

‘You see now the Penzance people came over cos Penzance and we never agreed – the footballers can never agree. Newlyn and Penzance always fallin’ out and fightin’. Well now our men come to think well we shall have to do something – we can’t go on like this – we shall have to call a meeting. So my dear life they called a meeting, the Porthleven men, the St Ives men and the Mousehole men all met together up Paul and they called this meeting you see – well we shall have to do something to drive these men from going to sea on the Saturday and Sunday. Well now come went on a week or two and in the end of course our men went to board the boats as they were coming in, the Lowestoft boats, as they were coming in the harbor so our men went aboard their boats and some of them took the fish and threw them all away. Well now by the means of that of course, the packers, because when the Lowestoft men used to come they used to bring packers with the buyers who used to buy the fish- Cushway and Wren and all they big buyers from Billingsgate. They used to come down and well they would bring all their packers with them. Well now course the packers didn’ like that and they of course interfered with our men’

James Guy

James Guy

The Penzance officials and community sided with the Lowestoft fishermen against their fellow Cornishmen, with many Penzance men volunteering to help the police and soldiers subdue the rioters. Another first hand account from Ruth PENDER gives an indication of the strength of bad feeling that Newlyn people continued to hold against Penzance after the riots, when she says that ‘her mother never bought a bit of meat anymore off a Penzance butcher’.

There are records which suggest that up to 200 East Country boats were about to come into Newlyn harbour to land their fish. Unfortunately, there is no photographic evidence because the only reporter on the scene had his camera thrown into the sea to prevent the rioters being identified. In an attempt to prevent the troubles escalating, the Harbour Master William OATES STRICK was dispatched in the steam vessel Nora to warn these East Coast fishermen not to try to enter the Newlyn harbour. However, this action caused considerable additional tension in Newlyn with much anger aimed at the unfortunate Harbour Master.

Eliza Jane describes the events as the unfolded:

Well it went along so bad that in the end the harbor master William STRICK went out in another boat to stop the fleet from coming here because if he didn’t would have been bloodshed cos now they started to fight. Well now the Penzance people started to come over and made things worse and in the end we ‘ad to ‘ave the soldiers down from Plymouth. Well it went on all the day like that – you know – fightin’ and then some of the policemen was being insulted and one thing and then ‘ow many arrests I couldn’ tell you. Well now father, my father said ‘Now you’re not to go on the pier mind’. This is in the mornin’ early “You’re not to go on the pier” but Susie went and I said “Well I’m goin’ too” and so I went along the pier too. But any’ow it was a terrible job and all night soldiers was there and everyone was up in arms you know. At 1 o’clock we’d gone to bed and at last we heard some shoutin’ and screechin’ now ‘’ow can ‘ee go to bed ! ‘ow can ‘ee go to bed ! ‘ow don’ ‘ee come down women an’ everybody. Bring if you ‘aven got nothin’ to protect ‘ee bring your shovel and your poker with ‘ee’’

Reports suggest that several policemen were injured in violent scuffles, including Inspector MATTHEWS, and the office of a fish seller HOBSON was destroyed. Telegrams requesting urgent assistance were sent to the Home Secretary with the result that by the early evening on the second day of the disturbances, 330 redcoats of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Berkshire Regiment arrived at Penzance station. By this time the Newlyn and Mousehole fishermen were joined by fishermen from St Ives and Porthleven. A determined fight ensued alongside the Lareggan River between the Penzance crowd, who sided with the Lowestoft fishermen, and those siding with Newlyn. A strong police force, assisted by the military, eventually ended the disturbance.

The military marched to Newlyn that evening, accompanied by several hundred Penzance people who occupied Newlyn’s south pier. A torpedo destroyer arrived later that evening from Plymouth followed by three more destroyers, ensuring that no more disturbances took place. So concerned were the authorities about further trouble that for about 10 years after the riots, gunboats continued to patrol Mounts Bay during the height of the fishing season.

As the riots subsided, there were a number of arrests including ‘Gib’ TRIGGS and Alfred GREEN, who were sent to Bodmin Assizes. The Cornishman newspaper provides a dire description of the men involved:

… with a number of evil-disposed persons unlawfully, rioutously and routously did assemble and gather together to disturb the public peace, and then unlawfully, riotously and routously and tumultuously make a great noise, riot and disturbances to the great terror and disturbance of her Majetsy’s subjects.

Parliamentary records show that the government of the day took the disturbances very seriously and Hansard records make interesting reading. One Member of Parliament asked whether the Government was prepared to introduce for Cornwall a Measure on the lines of the Irish Coercion Act. Another referred to the ‘barbarous onslaught’ made upon the Lowestoft fishermen and called for the ‘British Fleet to defend them’. Yet there was also support for Newlyn protestors with the MP for Gateshead asserting that the East Coast fleets ‘had no right to fish in waters not adjacent to their own, and that the Cornishmen were entitled to take the law into their own hands. He hoped the First Lord of the Admiralty would be able to assure the House that justice would be done’.

Nine of the Cornish fishermen were charged and sent to the Bodmin Assizes where three of the men were acquitted or shown mercy and six were sentenced to be bound over for twelve months to keep the peace. On their return, there was only a small peaceful crowd to receive them at Penzance station but at Newlyn there was an enthusiastic welcome with bunting and a band. Eliza Jane described it:

Well there was a lot of arrests you see cos now the men began to thump the policemen and one thing and another and a good many was arrested. Gib TRIGGS was the ringleader and when he came home we had the Paul band out for’un. I can see him coming over the bridge now.

Those who refused to fish on a Sunday raised a Star flag on the mizzen mast, but even this eventually died away and large company-owned steam drifters gradually put many of the local boats out of business, including Eliza’s own father. Her husband Edgar REYNOLDS was forced to abondon his life as a fisherman. Eliza explains:

‘My husband was a fisherman, we couldn’t get a living. The first winter we were married (1908), my husband got eight shillings all the winter – good job I had a few pounds by me.’

Eliza Jane and Edgar eventually had three children, when he died prematurely in 1932 when a workman fell from a ladder on top of him as he passed by. Newspaper accounts indicate that he was opposite the labour exchange at the time and is described as an unemployed general labourer. A very sad end for a man who had been a proud fisherman since his early teens.

The immediate aftermath of the riots saw no immediate changes with the East Coast fishermen continuing to fish on a Sunday to the demise of the local fishing fleet. However, recent years have seen the resurgence of Newlyn as a vibrant fishing port and it is now one of the largest and most flourishing ports in the UK.

Dr Lamorna Spry

Dr Lamorna Spry

My career was in science and technology but I’ve had a lifelong interest in Cornwall and its history, and so when I retired, I studied for an MA in Cornish Studies at the University of Exeter.

The dissertation was on the Newlyn Riots of 1996, which had a personal resonance since my own family were directly involved.

I enjoy bringing history to life through the power of storytelling and currently help organise the monthly “Cornish Story Live” sessions on Zoom, which has enabled us to reach the Cornish worldwide.

Well ! what do you know ? Such an interetsing little known story assembled as would a be jigsaw.Much enjpoyed. Thank you Lamorna.