On 25 February 1922 Isaac Foot was elected to the House of Commons as Liberal MP for the Cornish constituency of Bodmin in a byelection. This event was to lead to one of the most famous careers in Cornish politics. In the short term it was seen at the state level as a key milestone in the process that led to the collapse of David Lloyd George’s coalition government and locally as a catalyst in the post-war revival of Cornish Liberalism. One might add that Foot’s victory also resulted in one of the most famous dynasties in British politics with one son Michael becoming leader of the Labour party in the 1980s, his brother Dingle joining the cabinet in the 1960s, John serving as a Liberal peer in the House of Lords and yet another son, Lord Caradon, serving as the last Governor of Cyprus. This centenary commemoration by the Institute of Cornish Studies explores the 1922 byelection in the context of both Cornish and British politics. A team of three researchers explore the story of Foot’s victory. Bob Keys looks at the wider picture of the changing electoral fortunes of the Liberal party in British politics. Such circumstances were hardly conducive to a successful career and Foot was to struggle to retain Bodmin in the inter-war period with subsequent defeats in 1924, and 1935. Chris Carter from the University of Edinburgh then focuses on the early years of Foot before he became MP for Bodmin and Garry Tregidga explores the reasons for the victory in 1922 along with its implications for the cause of progressive politics.

1922 in Context by Bob Keys

The victory of Isaac Foot at Bodmin in 1922 needs to be placed in a wider context of developments in British politics in the first quarter of the twentieth century. How was it that the Liberal Party went from its landslide victory of 1906 with about 400 seats to third party status with a mere 40 seats by 1924? How did Foot win when his party was in long-term decline in British politics? Some historians have traced its rapid decline to the effect of the First World War and the rise of the Labour Party and to changes in the nature and composition of the electorate, manifest in the Party’s ambivalent attitude to the Suffragette Movement and Votes for Women. Others have focused on splits within Liberalism, seeing it as a coalition of opposed interests rather than a coherent intellectual movement.

Most famously George Dangerfield in his original 1935 work, had traced the ‘Strange Death of Liberal England, to splits and external threats already manifest in the earlier period from 1910-1914. 1 Trevor Wilson by the 1960s was focusing on the events of the First World War. He looked at its overall decline and lack of a return to popularity from 1914 all the way on to 1935 and perhaps even to the present day 2 Was this decline inevitable?

For Dangerfield the combination of various factors, including most importantly the suffragette movement and Votes for Women, Irish Nationalism and problems of the Celtic Fringe, which combined with the growth of labour unrest and the rise of an independent Labour Party, were all to become decisive factors, even before the war broke out. Cook on the other hand has argued that it was largely the impact of the war itself that accelerated the Party’s decline and exacerbated the divisions within it. 3. It was Kenneth Morgan, however, who analysed the crisis in more detail and pointed to the internal crisis over the ‘war contingencies’ that led Asquith to step aside and allow Lloyd George to become Prime Minister, with all the consequences that followed and have been well documented by historians and political scientists in the immediate post-war period. 4 The divisions within the party proved therefore every bit as important as the external threats to its continuing success and survival as an effective national political organisation during this period.

The 1922 election had seen a Conservative government returned to office, but in Cornwall Isaac Foot was returned again as MP for the Bodmin constituency. Foot’s position as a significant figure in Cornish Liberalism will be dealt with in more detail later in this study by Chris Carter and Garry Tregidga. The subsequent election in 1923 saw the emergence of a hung parliament and a coalition of Asquith’s Liberal Party with Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour. When this failed the 1924 election proved even more disastrous for the Liberal Party and confirmed its future status as the ‘third party’ in British politics from henceforward.

Despite being faced by the intellectual challenge of socialism and Labour, it is clear that Liberalism, as a political ideology was far from being moribund, for in this period intellectuals as significant as Hammond, Brailsford, L T Hobhouse and J A Hobson had all contributed to a renewal of its nineteenth century Gladstonian legacy. Its claim to be the standard bearer of economic liberalism and the defender of political democracy against ‘One Nation Toryism’, despite the evident splits within its own ranks over ‘imperial preference’ and threats to the Union. The party’s strength in the Celtic fringe, from Cornwall to the Hebrides, reflected its continuing appeal to provincial centres of dissent, non-conformity, and chapel folk across the kingdom, alongside its continuing strength and appeal to the metropolitan middle and professional classes. This has led some to blame its problems as personified in the party of Asquith on the one hand and Lloyd George’s ‘liberal opportunism’ on the other. From that perspective this was the key factor in its eventual collapse in the period from 1916-1924. Despite the confident modernism that was presented in party literature, the Party was reduced to a mere rump of its’ former predominance.

In all of this, where does Cornwall and Isaac Foot’s victory of exactly one hundred years ago stand, and what does it tell us of the future of Liberalism and Radicalism in Cornwall (and indeed British politics) today. And how was the later history of Cornish radicalism and the Liberal Party in Cornwall related to the varying careers reflected in the later generations of the ‘famously political’ Foot family and the very different contributions they continued to make to Cornish life? That will be a story to be explored in subsequent articles and podcasts in this series.

The Rise of Isaac Foot by Chris Carter

Antecedents

The Foot family shone brightly across the twentieth century. From the city of Plymouth and Cornwall’s borders, they played a substantial role in British public life. Every dynasty has a founder, and we begin with Isaac senior, from Horrabridge in Devon. Isaac senior arrived in Plymouth as a humble journeyman. What followed was a remarkable story of social mobility, as over the next four decades, he played a significant role in Wesleyan life in the city and became one of the major builders in the area, helping construct some new neighbourhoods, such as Lipson and St Judes. Some of Isaac senior’s sons followed him into the building trade. Two of his younger sons became lawyers, while a daughter married a lawyer. While much has been made of his son, Isaac Foot junior’s humble start in life, this is only partly true. By his early teens, the Foot family was upwardly mobile and prosperous, playing a prominent role in Plymouth’s religious and business life.

Isaac Foot junior (hereafter Isaac Foot) has been the subject of affectionate and insightful treatment by members of the Foot family. 5 While much is known about his later life, this chapter focuses on the rise of Isaac Foot, as seen through the prism of the newspapers. 6 Our focus is on the period from 1900 to 1920, taking Isaac from the age of 20 through to 40. While our account lacks the intimate richness of the Foot’s insider accounts, it attempts to shine a light on the rise of Isaac Foot’s public career.

Wesleyan Life:

Isaac Foot’s early adult life was forged on the anvil of the Wesleyan creed. At the tender age of 19, he qualified as a lay preacher, as his father had before him. The Wesleyan scene was vibrant, both in Plymouth and the counties of Cornwall and Devon. At the dawn of the Twentieth Century, Wesleyans were confident and well organised. Its chapels were well attended and while still the religion of choice for working class people in Devon and Cornwall, increasingly the movement was producing prosperous business and professional types.

The first reference to Isaac Foot junior in the newspapers was his presence at the Plymouth Wesley Bazaar in April 1900. The event was ‘for the purpose of clearing a debt upon the Wesley Chapel School Buildings in Ebrington Street. 7’ Concerts arranged by Miss Baily and Miss Goff were given in the afternoon and evening. Isaac Foot jr was among the assistants. Similarly, in December 1900, he organised a ‘household stall at the Wesleyan Chapel bazaar on Ham Street. 8 The newspapers from this period recount numerous similar events he was involved in. He was part of busy Plymouth Wesleyan life, which was energetic, dynamic and heavily supported.

In November 1900 the Western Morning News advertised that the following day Isaac Foot Junior was speaking at the King Street, Wesleyan Church as part of the Foreign Missionary Anniversary.9 It noted he was the Secretary of the Plymouth Wesley Guild, his first leadership position reported in the press and notably an early foray into foreign affairs. He was 20 years old.

His role as Secretary of the Plymouth Wesley Guild was a busy one, with many trips to other Guilds. It also provided a platform for him to speak, where he clearly rose to the occasion. The Cornish and Devon Post reported that in Wadebridge ‘a very profitable evening was spent at the Wesley Guild when Mr Isaac Foot, jnr, secretary of the Plymouth Guild, gave a splendid address on the guild’s work and its aims.’10 The Guild movement arranged holidays for its members, in 1901 the Warwick and Warwickshire Advertiser reported that the Guild’s gathering on Good Friday in Cambridge.11 Here Isaac Foot jnr ‘advocated the duty of town Guilds helping country places, and told how his own Guild last summer chartered a steamer, and with 160 of the members paid visit to a struggling village cause up the neighbouring river, carrying warmth and encouragement to their country friends’. In summer, 1901, some 400 members of the Plymouth and Devonport Guild headed by train to Kingsbridge for their annual outing. At an opening air assembly the ‘speakers were Revs Cuthbertson, Silox, Huggins and Isaac Foot Jnr’. Foot was a mere 21 years of age and addressing an audience of over 500 people. The Western Morning News relayed to its readers that the ‘proceedings were of a hearty character and, altogether the day was a very happy one’.12 His capacity for leadership and public speaking were evident from an early age.

Isaac was clearly a young man making his way in life. In May 1901 at the Plymouth and District synod it was announced that Isaac Foot had taken 2nd place in the Wesleyan correspondence course exams, or as the Western Morning News noted ‘Mr Foot was placed second in all of England’.13 This success was shortly followed by the Plymouth Ebenezer Wesleyan Circuit electing him as their Education Secretary. Foot was just 21 but had emerged as an important figure in Plymouth Wesleyan circles, given his educational, organisational and public speaking successes.

In 1901, we see the first direct intersection of his Wesleyanism with politics. The Wesley Guild convened its own Parliament in Plymouth, where it debated the political issues of the day. The Parliament followed Westminster procedures very closely and is a fascinating example of the Wesleyan commitment to self-improvement and education. It also illustrates that radical liberalism was the de facto political wing of the Wesleyan movement. In 1901, the Western Morning News reported bills being debated on the ‘evils of gambling’, a motion ‘earnestly supported by Isaac Foot (the Prime Minister)’.14

Foot’s prowess as a performer continued to grow. In addition to preaching and presenting to large audiences at various chapels, he branched out into delivering public lectures. One of his staples was ‘Abraham Lincoln: lawyer and statesman’, which the Western Morning News reviewed positively: ‘much reading had been compressed into an hour’s presentation’ and was ‘attractively presented’.15 When delivered in Callington, the Cornwall and Devon Post enthused ‘on Monday evening Mr Foot delivered an excellent lecture on Abraham Lincoln, lawyer and statesman, whom he called the greatest of all Americans’.16 Of other lectures, one is described as ‘full of power and advice’, while his ‘popular lecture on William the Silent: the Reformation in Holland’, attracted a ‘fine audience, and the lecture was greatly enjoyed’.17 The good people of Calstock ‘greatly enjoyed Foot’s lecture on Gladstone which elicited frequent applause’. 18 By the age of 23, Isaac Foot was a noted public speaker, both as a popular lecturer and lay preacher.

The Lawyer

Given his skills of oratory and academic ability, Isaac Foot’s decision to pursue a legal career should be of little surprise. His father’s prosperity allowed the purchase of an article clerkship, training with Messrs. Skardon and Phillips. He qualified in 1902 and was enrolled as a public notary in 1903. It is in that year that we find the first newspaper references to Isaac’s legal career, when he working out of the Old Town Chambers in Plymouth. The life of a newly minted lawyer was varied, he acted on the sale of a number of properties and the first court case reported was his defence of a boy who had sadly blinded another boy in one eye. The paper tells us: ‘Mr. Foot contended that defendant had no malicious intent in throwing the stone; in fact, it was an act of boyish thoughtlessness. He asked that he might be dealt with under the First Offenders’ Act’.19

Isaac Foot’s legal career connected directly with organised Wesleyanism and radical liberalism through the 1902 Education Act. One of the consequences of the legislation was that Nonconformists would be helping fund Anglican schools through the payment of their rates. The Passive Resistance Movement sprung up, under the leadership of John Clifford, to resist the Act. Over the next two years, around 140 Non-Conformists were jailed for not paying the rate, while thousands more were subject to court action. Isaac Foot jnr, the younger lawyer, became centrally involved in the dispute. The Cornwall and Devon Post described Mr. Foot as a rising young lawyer and told their readers ‘it may be interesting to note that he represented the large number passive resisters recently at Plymouth’. The Western Morning News described how Isaac Foot acted as lawyer to the Devonport Citizens’ League, representing passive resisters in court, ‘defending in many cases’.20 Isaac Foot’s involvement in the dispute was primarily conducted in the courts but on occasion spilled out into public debate. For example, he had a sharp exchange with the editor of the Western Morning News, declaring ‘The men and women who appeared [in court] were those whose names were and have been for very many years, associated with the religious life of this town’. 21 Isaac’s advocacy for Plymouth’s passive resisters led to instructions from resisters elsewhere, including various radical liberals.

The Fledgling Politician

The Passive Resisters movement put Isaac Foot, as a lawyer in his early 1920s, in the front line of a dispute that directly challenged his community. Respectable Wesleyans, many of whom were pillars of local society, were criminalised. It sharpened the connection between politics and religion. It is in 1904 that we get the first report of Isaac Foot speaking at a Liberal Party meeting in Kingsbridge. The Western Morning News described his speech as ‘racy’.’22

In September 1904, Isaac Foot made his first bid for electoral office, a place on Plymouth’s City. He stood as the Liberal candidate for the Charles Ward in Plymouth. It was a three way contest between the Conservatives, Liberals and the Social Democrats; thus potentially splitting the progressive vote. The newspaper reported that the Social Democratic candidate ‘had been endeavouring to drag something up from Mr Foot’s past history. They said that four/five years ago he belonged the Social Democratic Federation. He admitted he joined it because at the time its views were right, but got so sickened of it he severed his connection. He found that the journalists which supported it was rotten with scepticism and atheism … He was a Christian Socialist, and the principles of Christian Socialism are best obtained by genuine, true, and broad Liberalism’.23 That Foot identifies with socialism is fascinating, as is the way in which he nests it within Liberalism. These are, of course, early attempts at developing a political philosophy.

In a Hurry

By the time Isaac Foot hit his mid-twenties, he was well known in political, religious and legal spheres through Devon and Cornwall. His career was increasingly storied with the newspapers reporting frenetic activity in these three interconnected areas of his life. This was punctuated by his marriage in October 1904, which the Cornish and Devon Post reported as, ‘One of the prettiest nuptial ceremonies ever celebrated at Callington was solemnised the Wesleyan Church on Thurs day afternoon, the 22nd ult., the presence of about 600 persons. The bridegroom was Mr. Isaac Foot, solicitor, of Plymouth, the fourth son of Mr. I. Foot, builder, of Plymouth, and the bride was Miss Eva Mackintosh, only surviving daughter of the late Mr. A. Mackintosh. M.D., of Chesterfield, and granddaughter of Mr. W. Dingle, J.P., of Callington’.24

His activities of preaching, organising, lecturing and advocacy continued at pace. In 1905, when The League of Young Liberals were formed in Plymouth, Isaac Foot was elected chairman. The Western Morning News described him as the ‘local chairman of a militant society’. His legal work with passive resisters continued and he became a passive resister himself, now a rate-payer following his marriage. In 1905 he was elected as a layman to the Methodist synod. Electoral office remained elusive, with a further defeat, this time for the ward of Compton in the council elections of 1906. The following year, at his third attempt, he was elected for the Greenbank ward to serve on Plymouth City Council. In the same year, his first son, John, was born, to be followed by six further children over the next decade. In 1908, he joined forces with Edgar Bowden, his long-standing friend, to form the legal practice Foot & Bowden.

The Candidate

By his late twenties, Foot’s enormous energy, academic ability and public speaking gifts had elicited attention beyond his native Plymouth. In 1908 he was invited to join the Eighty Club, the London based elite Liberal Party gentleman’s club. He was talked about as a potential MP:

“Mr J.A. Loram presided at the inaugural meeting of the Exeter branch of the League of Young Liberals, and introducing Mr Isaac Foot, of Plymouth to the meeting, he said if rumour was not a lying jade, he believed Mr. Foot would try conclusions either in the Totnes Division or in some other division in the county with some one of other of the Tory Tariff Reformers at the next election … for he was a man who would do credit to any constituency”. 25

In 1909, he was adopted as the prospective parliamentary candidate for Totnes. He was familiar with the constituency, often preaching in the area. It was not viewed as a winnable seat but would, nonetheless, offer Isaac Foot useful experience. His adoption as candidate was reported very positively by the Totnes Weekly Times:

“Isaac Foot is one the most prominent, energetic, and able liberals of the younger generation in the West of England… As a speaker he has an incisive argumentation style, a poignant humour, an admirable voice, and a command of rhetorical resources, which promise well for his career politician… Mr Foot is a sound Liberal sans phrase, a true Progressive by instinct and by education, and an effective organiser, as well as an eloquent speaker”.26

In the nine months after his adoption as the prospective candidate for Totnes, the Dartmouth & South Hams chronicle reported that ‘since that time nearly 200 meetings have been held on his behalf, and at almost all of these he has himself spoken’. At his formal adoption, ‘he addressed a densely crowded audience at the Assembly Rooms, when he received an almost princely reception’. 27

During the short campaign in January 1910, Foot campaigned with characteristic vigour and energy. On polling day itself, a beautiful winter’s day, at Dartmouth, ‘great excitement was shown throughout the day. The Liberal candidate was carried through the crowd, and after visiting the polling station, his carriage was dragged through the streets, four Jack-tars taking a prominent part’.28 While Sir Francis Mildmay recorded a comfortable majority of 1927 votes over Isaac Foot, it was widely regarded that the defeated Liberal candidate had fought an inventive campaign. The day after his defeat, he visited Kingsbridge, one of his strongholds:

“A tremendous crowd met Mr Foot outside ‘Roselands’ Mr Harris’s residence, and on the candidate appearing, to get into the carriage awaiting, he was met with round after round of cheering, and the singing of ‘He’s a jolly good fellow’. Perfect order existed among the great crowd. The horses had been removed from the carriage, and Mr Foot accompanied by Mr Harris and Mr Spear, were drawn in procession through the principal streets of Kingsbridge and Dodbrooke. The cornet player on the box-seat led the singing of Liberal songs. ‘The Land Song’ being the favourite. When the procession returned to the Liberal headquarters, considerably over a thousand people stood in the street to listen to addresses by Mr Foot and others from the committee-room window.’29

With a further election anticipated at the end of 1910, Foot continued his frenetic campaigning. He journeyed through the constituency, attending meetings and giving speeches. He was adopted once more as the candidate for the Totnes constituency but surprised many in the constituency when he switched to fight Bodmin in late November. This decision invited ridicule in the Western Morning News. Resurgam, a columnist, wrote:

“There is weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth, for our Isaac, the Child of Promise, has deserted his first love and taken on with another. We little thought that, after all his protestations of fidelity, our Isaac would have brought his engagement so abruptly to an end.”30

The One That Got Away

The Bodmin constituency, which had been in Liberal hands since 1906, had three MPs in quick succession. The courts struck down Thomas Agar Robartes’ 1906 victory for electoral fraud. Freeman-Thomas won the subsequent by-election and worked directly for Asquith. He stood down before the 1910 election, subsequently pursuing a successful career as a colonial administrator. Cecil Grenfell fought and won the January 1910 election. The victory of 50 votes was wafer-thin and signalled the deep divisions within the country. Grenfell’s victory was against Sir Reginald Pole Carew, a Boer War hero and well-known local aristocrat. Grenfell decided against standing again at the very last minute.

The Bodmin Liberal Party selected Isaac Foot as their candidate. The Western Times reported: ‘Mr Grenfell having decided not to seek re-election, and that gentleman’s majority being extremely small, a strong local man was a necessity; and as Mr. Foot is well-known in the constituency, he was asked by the Liberal Headquarters to transfer his services. It is to be hoped that he will be able to retain the seat for his party’.31

Foot marked a notable contrast with previous Liberal candidates. Agar Robartes was the eldest son of Viscount Clifden and heir to the vast Lanhydrock Estate. While attending Christ Church, Oxford University, Agar Robartes was a member of the Bullingdon Club, whose concerns were far removed from Wesleyan values. Freeman-Thomas was an Old Etonian, and diplomat turned politician. Grenfell was an Old Etonian, former army officer and Pascoe Grenfell’s grandson, a famous nineteenth-century politician. Grenfell was married to the Duke of Marlborough’s daughter. These candidates had successfully won the Bodmin constituency (in 1906, 1906 and 1910 respectively). They were either aristocrats or drawn from upper-class backgrounds. One was Cornish (Agar Robartes), one from Cornish stock (Grenfell), and one from the military/diplomatic service (Freeman-Thomas).

Bodmin’s Liberal MPs came from the British Establishment, a situation mirrored across the country. Isaac Foot represented a new breed of Liberal politician. A Wesleyan Methodist and proprietor of a solicitor’s practice, Foot was part of the new middle class. Through his efforts and his father’s success, Foot was monied, but it was ‘new money’. Of equal note, he was not Cornish. While he was from nearby Plymouth, this was a world away from rural Cornwall, but through marriage, Foot had a connection with the constituency. Moreover, through the Wesleyan circuit, he was a familiar and much admired preacher.

Rivalries between the Liberal and Unionist parties had ran deep in the Bodmin constituency during the Edwardian period. Each election was hard-fought, with controversy never far away. In January 1910, Grenfell squeezed home for the Liberals in Bodmin. The Cornubian and Redruth Times reported, ‘The announcement came as a severe shock to the Conservatives in Cornwall’. From the very outset, perfect confidence had reigned in that camp. They openly boasted they were going to win’.32 In the General Election that followed in December 1910, Sir Reginald Pole Carew was once again the Unionist candidate. He was a popular landowner and retired general: ‘Sir Reginald Pole Carew is very popular in London society, of which he was one of the pets a few years ago, when his admirers used to call him the handsomest man in the British army. He did fine service in the Boer War, commanding the Brigade of Guards, and subsequently handling the 11th division with much skill…Sir Reginald married Lady Beatrice Butler, a daughter of the Marquess of Ormonde, who is one of the most beautiful women in society’.33

The campaign was hard fought but humour was very far away, throwing up some entertaining episodes, ‘Mr Isaac Foot at Antony:- ‘Vote for Pole-Car-EW’ piped a shrill feminine voice from the doorway, ‘Cock a-doodle doo!’ replied Mr Foot and the audience had a good laugh.’34 Similarly, Unionist literature implored voters to ‘give Foot the boot’. The campaign was delicately poised and hard-fought. Isaac Foot was undoubtedly disadvantaged entering the contest late.35 Pole Carew prevailed by a mere 41 votes, ‘Soon after two o’clock another gratifying result came in – that of the Bodmin division, for which General Pole Carew had been returned. At the last election he was defeated by Mr C.A. Grenfell by 50 votes. At this election his opponent was Mr I. Foot, a solicitor, who opposed Mr Mildmay in the Totnes Division last January. Mr Foot was, of course, glad to give up a hopeless task for the more promising one of retaining Bodmin for the Radical Party. But for the second time in succession his claim to a seat has not been recognised’.36 The Western Times took a different view, ‘Mr. Foot has doubly earned the gratitude of every Liberal. In obedience to a call, he entered the lists at the eleventh hour, fought a territorial magnate of much influence and popularity, and ran him up 41 votes. Pluralists eliminated, Mr. Foot would probably have had a majority of at least 700 votes. Here, again victory will most certainly be achieved another time. The constituency is Liberal, and the Liberal Party must have it.’37

The Coming Man

While Isaac Foot had failed to win Bodmin, he has firmly established himself in South East Cornwall as a candidate, and was, by now, recognised as one of Devon and Cornwall’s leading liberals. His gifts of oratory, combined with frenetic activity and a capacity for organising had gained the respect of the liberal community. This community was also deeply embedded in non-conformist religion. He was active in the Wesleyan synod and on the preaching circuit. He was also an elected councillor in Plymouth, which meant he was familiar with the pragmatic realpolitick of local government.

Isaac the Ascendant: Years of Hope

In January 1911, Isaac Foot toured Liberal clubs around the South-East Cornwall constituency. In Liskeard he received an ‘extremely enthusiastic reception’,38 which included ‘an excellent musical programme’, while at Lostwithiel Liberals were ‘not downhearted’ but asked ‘could there have been a better compliment paid Mr Foot than the action of their opponents, who, on hearing of the executive’s selection, at once redoubled their efforts, and bombarded with all the big guns – and the little guns – they could command. Wealth and territorial influence had been arrayed against the Liberal party’..39 The Methodists were equally positive, at a meeting at Callington, ‘Mr Isaac Foot jnr , of Plymouth, who was received with an outburst of applause’ recounted that ‘Whenever he looked upon a village chapel there was always an involuntary suggestion made to him in the words “What mean ye be these stones?” It indisputably meant heroism and sacrifice. They were built by the pence of the poor, and not by the wealth of the rich’.40

Throughout this period, Foot maintained a hectic schedule of Wesleyan and Liberal activities. In this regard, he embedded himself within the social fabric of South-East Cornwall, for instance, The Hon Tommy Agar Robartes, at a meeting at Lostwithiel, hoped to ‘welcome and hear their late candidate and future member, Mr Foot’.41 He remained a councillor in the City of Plymouth and through the Eighty Club and his status as a leading West Country Liberal, spent more time visiting Westminster. For instance, in February 1911, the Holsworthy Wesleyan Guild reported ‘an eloquent lecture on Sir John Eliot was delivered by Mr Isaac Foot, Liberal Candidate for the Bodmin Division … Mr Foot came by the 7 o’clock train direct from London. He attended Mrs Asquith’s reception on Saturday evening, and would have remained for the opening of Parliament but for his engagement to lecture at Holsworthy’.42

Home Rule for Ireland became the dominant issue in Parliament in the early 1911-14 period. Isaac Foot was firmly on the side of the Home Rulers. Much of his political activity in this period was given over to arguing for Home Rule. It was an argument that was potentially difficult for a nonconformist to make, something Foot dealt with head-on: ‘Going on to deal with the appeal which was being made to Cornish Nonconformists to oppose Home Rule, he said all of humbug and hypocrisy of which he had ever heard, this particular appeal was the greatest’, continuing ‘a few years ago Nonconformists were the Despised Dissenters. Now they are the Noble Nonconformists’… ‘he did not think the Conservative Party would get many Nonconformists into their parlour’.43 In 1912, a large rally was organised at Victoria Park in Plymouth in favour of Home Rule. Over 5,000 people attended to hear a range of speakers, including leading members of the Irish Party. Isaac Foot was one of the speakers and received a rapturous response.

Liberal politics was focused on social reform and Home Rule. As late as July 1914, the focus was on the expected 1915 general election. Isaac Foot and his agent, CA Millman, hosted political agents from across Devon and Cornwall. In a rousing speech, Foot ‘impressed upon the agents the importance of being ready for the next big fight – perhaps the most important in political annals – that would take place next year’.44 These were prophetic words, though the fight was to be very different to the one Foot envisaged

World War One

The outbreak of World War One took most commentators by surprise. Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister, and Sir Edward Grey vacillated as to whether to enter the conflict. The series of interlocking alliances propelled Europe into a major war.45 The lack of a quick conclusion to the war had dramatic consequence that cast a long shadow over the twentieth century. The clashes between Liberalism and Conservatism on constitutional questions moved to the periphery as the nation mobilised to fight the war. The onus was now on cross-party collaboration, in light of this the first newspaper reference to Isaac Foot during the war is in September 1914, ‘Arrangements are being made for a public meeting at Liskeard to-morrow evening, to be addressed by Sir Reginald Pole-Carew…and Mr Isaac Foot, the Liberal candidate, will be invited also to be present’.46 At a similar cross-party meeting at Fowey, ‘Mr Isaac Foot also gave a very stirring address’.47 In Plympton, Foot appeared at an army recruiting meeting alongside the Conservative MP, Sir Waldorf Astor, and Sir Henry Lopes.48 By October 1914, Foot had a theological lecture on the nature of war, presenting ‘Has Corsica conquered Galilee?’ in Bodmin.49 His argument was that the war was ‘not merely a material fight but a spiritual fight’50 As party politics was, in effect, put into cold storage, Foot’s public speaking continued but its focus was in Wesleyan Guilds and chapels.

Isaac Foot’s legal work is reported in various newspapers, during 1914 & 1915 it is the routine property sales and court cases. This changes in 1916, when conscription is introduced. In July 1916, The Law Society recommended that Foot be granted ‘conditional exemption’ from military service on the basis of age and family situation,51 which was granted. Isaac Foot’s legal work expanded greatly as he acted for employers52 and employees seeking exemption from military service .53 54 Foot’s legal work continued throughout the duration of World War.

In 1916, Sir Reginald Pole Carew, following a riding injury, stood down from Parliament leaving a vacant seat. Foot and the Liberals did not contest the seat – given war-time – and Charles Hanson, a coalition Conservative was declared the new MP. As the war finally ended in November 1918, party politics resumed, although they were far from normal. The Liberal Party hoped that there would be a delay before a general election, but suspected Lloyd George would go to the country.55

Isaac Foot was adopted at the Parliamentary candidate for S-E Cornwall, described as a ‘prominent Plymouth solicitor, who is well-known in Non-Conformist circles throughout Devon and Cornwall’.56 The split in the Liberal Party was deeply problematic for Foot, as was the timing of the election. One supporter wrote a long exegesis to Foot, in the pages of the Cornish Guardian, concluding: ‘Your spiritual home, if you will allow me to say so, is in the Labour movement, and it is pitiable if you are going to waste energies and abilities of a high order in the attempt to revive the corpse of official Liberalism.’57 Foot’s lack of a military record was used against him in the election, ‘Being a Liberal who has fought and bled in France, I should like to know whether Mr Isaac Foot will be able to attend the House of Commons regularly if elected. Not many months ago he successfully appealed to the tribunal for exemption from military service because he was indispensable to his business. If he was unable to leave his business to fight for his country, it is difficult to see how he will be able to find time to carry out properly the duties of a member of Parliament, and, incidentally, earn the £400 a year’.58 This cutting letter was signed off ‘Bodmin and France’.

In the election campaign, Sir Charles Hanson, the incumbent, exploited the divisions in the Liberal Party ruthlessly, asking ‘he is neither an Asquithian Liberal or a Lloyd George Liberal he has said. Then where was he? Throughout the division on bills he read: “Vote for Mr Foot, the popular candidate”, “Vote for Mr Foot, the Labour Democrat candidate”. Where was Mr Foot? He ought to define his position more definitely. No man can serve two masters”.59

Despite an energetic campaign, the timing of the election, the splits in the Liberal Party and personal attacks damaged his chances. The Cornish Guardian described how the Liberal campaign was ‘hampered by the lack of motor cars’ 60 It viewed a Hanson victory as probable, while a Foot victory as only possible. 61 It was perhaps no surprise when Sir Charles Hanson won the seat comfortably.

By-election and Aftermath by Garry Tregidga

The by-election was caused by the death of Hanson on 17 January 1922. Foot’s opponent was Major General Sir Frederick Poole who stood as a Coalition Conservative and had a distinguished record of army service in the Boer War and in Russia during the First World War. Supporters could also point to some local credentials. Although originally from County Durham, he could potentially tap into sympathy for the Hanson family since he was married to Alice, the daughter of Sir Charles. Sir Charles appears to have developed a personal vote in the Fowey area since he had been born in the area as the son of a Master Mariner, was briefly a Wesleyan minister and had an image as a ‘self made man’ from working in Canada rising to become Lord Mayor of London. Poole was presented in the press as ‘a Fowey man’ who lived in the area and subsequently became Deputy Lieutenant for Cornwall.62 Hanson had been ill for some time and in September 1921 it had been announced that Poole had been unanimously selected as prospective Coalition candidate to replace his father-in-law who intended to retire at the next general election. 63 The Conservatives also appeared confident that the strength of their party machine in the constituency would assist them in retaining the seat. 64 Foot agreed that his opponents had a strong organisation reflecting their ability to draw on ‘an unlimited sum of money’. He claimed that they ‘must have spent twice or three times as much as they did’. But he added the Coalition ‘could not purchase enthusiasm with money (Applause)’.65

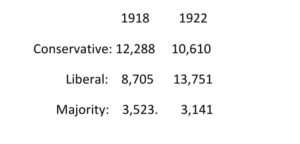

The final results appear to indicate that Foot and his supporters were able to generate enthusiasm for their campaign. Turnout increased compared to the general election and this was perhaps crucial since the actual Conservative vote had fallen by just 1,618 but the Liberals had added an extra 5,046 to their share. As a result the Liberal percentage share of the vote increased from 41.6% in 1918 to 56.4% in 1922. Weather conditions on polling day were favourable to the Liberals since in the morning it was reported that ‘Drizzling rain is falling. Later, the weather has cleared and there is every indication of a record poll’.66

Table 1: A comparison of the vote in Bodmin in 1918 and February 1922

Foot fought an energetic campaign in the by-election. In the first place it was noted that he was able to cover an extensive area of the constituency on a daily basis. For example, on just one day (22 February) he had ‘covered over 70 miles and spoke in 20 villages’.67 The Liberals were also able to tap into the concerns of discontented voters in an area that felt it was being neglected by central government. It was reported that ‘the agricultural vote is a heavy one, and this is said to have moved away from the Coalition since the Government reversed its agricultural policy’.68 Farmers were disenchanted because of a decline in farm prices, while agricultural workers voted Liberal in protest at lower wages. Across the political spectrum there was a view that the Lloyd George Coalition was not effective in its use of public funds. Bodmin Divisional Labour Party, for example, spoke of a ‘wanton waste of the country’s resources’.69 Foot concluded that he had ‘won because people were bitter and angry at broken promises, at the waste and extravagance, and because the people of that constituency thought that the Cornish miners had been treated with great meanness by the government’.70

This final point referred to the post-war collapse of Cornwall’s mining industry. It had emerged as a key election issue with Foot taking a great deal of interest both during and after the contest. His first question in the House of Commons ‘related to the distress amongst the Cornish miners’ and his sole ministerial position in the early 1930s (again at a difficult time for the industry) was as Secretary for Mines.71 The nadir of the industry’s fortunes after the First World War occurred in 1921/22 when unemployment in the far west of Cornwall rose dramatically leading to public concern over reports of local poverty. The government’s reluctance to offer financial assistance was criticised particularly since there was a perception that tin resources had been exploited for the war effort.72 The plight of the Cornish miners even featured in a campaign song composed for the by-election:

‘We’ll hold aloft our banner high,

Like Bannerman of yore,

With Asquith, Grey – true men are they

We’ll storm their castle doors;

The Coalition would not help

The Cornish miners poor

Come vote against them, ‘one and all’

And make them think the more

And shall our Isaac win

Say, shall brave Isaac win?

Yes, high above the Tory din,

Let’s bear good Isaac in!’73

The song is quite symbolic of the Liberal campaign with a style of language firmly rooted in the recent past. This can be seen in terms of the reference to 1906 when Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman had won the last historic Liberal landslide in British politics (locally the young T.C.Agar Robartes of Lanhydrock had won Bodmin after two decades of Unionist victories) along with the rural populism implicit in the line ‘We’ll storm their castle doors’. One might add that this approach was increasingly out of place in urban Britain but it still resonated in the Cornish countryside. Moreover, the song is actually a parody of the Cornish anthem ‘Trelawny’. This was part of a tradition in local electioneering that dated back to 1832. On that occasion supporters of Sir William Salusbury-Trelawney, a descendant of the famous Bishop, had sung a parody of the song when he contested East Cornwall for the Whigs.74 It was to feature regularly in subsequent elections including the interesting case of the 1906 Bodmin by-election. As was noted earlier, Robartes had been unseated just a few months after his victory in the general election following accusations of election bribery by his Conservative opponents. The Trelawny tradition was now linked to a defence of the honour of the Robartes family of Lanhydrock when yet another parody was used as a campaign song:

‘A good cause and a trusty hand

A loyal heart and true;

Our Tory foes shall understand

What Cornish lads can do,

And have they fouled Lanhydrock’s name

With slander and with lie?

Here’s Cornish lads, from Par to Rame,

Will know the reason why’.75

The enthusiasm generated by Foot’s campaign needs to be seen in this wider historical context. Both at the state and constituency levels there was a feeling that the Liberals had been in gradual decline since 1906. On the surface that process had appeared to have come to a close and the weeks following Foot’s victory were reminiscent of an earlier political age in South East Cornwall. Another parody of ‘Trelawny’ was composed as a victory song and ‘vociferously sung everywhere’ at celebration parties with village halls decorated with the ‘blue and gold’ (yet another reference to the past since the Bodmin Liberals had adopted the colours of the Robartes family for their local party rosette).76 Moreover, the use of parodies on the theme of ‘Trelawny’ suggest that Foot, though seen initially by some as a ‘stranger’ from across the Tamar, was now being presented as the champion of Cornish interests. His supporters claimed that he could now champion a region that was a ‘long way from London and unless the powers that be are made to realise that Cornwall does really exist and is entitled to some of the money that goes up from Cornwall … we shall not get what is our fair proportion of public expenditure’.77 The by-election victory reflected the restoration of the pre-war nexus of place and religion with Foot as the natural defender of local values:

‘Mr Foot has won a resounding victory in Leonard Courtney’s old constituency. The scenes on Saturday afternoon at the declaration of the poll beggared description. They were Cornish of the Cornish; the enthusiasm of Nonconformist farmers, of earnest young preachers, of dark-eyed women, and fiery Celtic youth had something religious about it. No such fervour could be seen elsewhere outside Wales’.78

Moreover, the absence of a Labour candidate ensured that the power of the non-Conservative majority was maximized. Unlike constituencies further west the Conservatives tended to have a reasonable chance of victory. Bodmin had been the only Unionist gain in the December 1910 election and the presence of a Labour candidate from the inter-war period onwards was seen as giving an advantage to the Conservatives. This was recognised in the early stages of the by-election campaign when one newspaper predicted that if Foot had ‘only a single opponent’ he would ‘win handsomely … A Labour candidate, however, would complicate matters very seriously’. 79 The local Labour party agreed with this analysis. It was reported that they had ‘unanimously decided to recommend their members to vote for the Liberal candidate’. With ‘a thousand voters’ registered as party supporters they claimed that this decision would significantly ‘influence’ the final outcome.80

Significantly, this move appears to have been supported by individuals at the state level. Leading figures like J.R.Clynes, leader of the Labour party, and J.H.Thomas, a future cabinet minister, publicly welcomed Foot’s victory and the defeat of the Coalition. Charles Ammon, who had won the North Camberwell by-election for Labour just two days before, sent Foot a message of support stating ‘Will meet you at Westminster’. 81 Indeed, there is evidence that the trio of by-elections from Clayton on 18 February, North Camberwell on 22 February and Bodmin on 24 February were planned experiments in a Liberal-Labour partnership similar to the old progressive arrangement of the early 1900s. All three seats saw gains in straight fights by the opposition parties with Labour winning the first two contests. At North Camberwell the Liberals had narrowly come second in 1918 and the result suggested that many Liberals were willing to vote Labour in certain circumstances.82 The Hull Daily Mail concluded that the three by-elections indicated that the Independent Liberals (or ‘Wee Frees’ as they were commonly known) were willing to work with Labour:

‘There was a tacit understanding between the ‘Wee Frees’ and Labour. Nothing on paper! Nothing ‘formal’, or ‘binding’. of course, but a marvellousy effective arrangement at the polling booth! Nearly every by-election will tell the same tale, and it really looks as if we are arriving at that millennium when ‘the progressive vote’ will be ‘split’ no more! 83

It is tempting to draw comparisons with contemporary politics given the recent discussions over a possible pact between Labour and the Liberal Democrats though in the present the emphasis tends to be on encouraging tactical voting rather than the actual withdrawal of candidates. Recent by-elections in 2021 like Batley & Spen and North Shropshire suggest that the party which is less likely to win will fight a relatively low key campaign to enable the non-Conservative vote to coalesce around the main challenger to the Johnson administration. A century after Foot’s victory the press are now speculating about a non-aggression pact at the next general election leading to a ‘confidence and supply’ agreement in the event of a hung parliament.84

But the aftermath of the 1922 Bodmin by-election is also a warning from the past of the problems associated with the formation of electoral alliances. Foot’a victory paradoxically encouraged opponents of collaboration in the Labour movement. On 4 March 1922 the chairman of the Gloucestershire Federation of Labour parties was critical of the move towards a Liberal-Labour ‘arrangement’ as a result of the three by-elections.85 In the following month collaboration was ‘soundly condemned’ at the Nottingham conference of the Independent Labour Party with Labour’s stance at the Bodmin by-election described as a ‘mistake’. The general feeling was that ‘There was no need for Labour to join with Liberals to overthrow the Coalition. Any Coalition … which had capitalism for its underlying object was bound to overthrow itself sooner or later’.86 This belief in the inevitable victory of Socialism was perhaps reinforced by gains like Clayton and North Camberwell along with the failure of the Liberals to sustain their breakthrough by narrowly failing to capture Inverness from the Coalition Liberals in another straight fight on 16 March.87 In June the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette published a letter from Labour activists in Barnstaple under the heading ‘NO MORE BODMINS’:

‘We are of opinion that the future of the Labour Party depends on its independence as a working-class political party, and urges the Parliamentary Labour Party to refuse any suggestion of alliances, understandings, or working arrangements with the Free Liberals … for the professed purpose of smashing the Coalition. We hereby set up the Barnstaple policy over against the Bodmin by-election policy … with a Labour candidate in the Barnstaple Division.’88

In practice Labour was not in a position to fight every rural seat in the inter-war period. This gave an opportunity for the Liberals to recover in rural Britain and Foot’s victory in 1922 was to provide an inspiration for many in his party who felt that a revival of ‘true Liberalism’ was now possible. But the goal of a new Labour-Liberal partnership both in Cornish and British politics was not achieved. A century later the exact nature of an anti-Conservative ‘understanding’ is still being discussed.

Notes and References:

1. George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England 1910-14, London, Constable, 1936, pp 7-9

2. Trevor Wilson, The Downfall of the Liberal Party 1914-1935, London, Collins, 1966, see Introduction and ff.

3. Christopher Cook, A Short History of the Liberal Party 1900-1984, London, Macmillan, 1984, (2ndEd) pp 60-65

4. K O Morgan, The Age of Lloyd George: The Liberal Party and British Politics 1890-1929, London, Allen & Unwin, 1971, pp. 67-70.

5. Michael Foot and Alison Highet,, Isaac Foot: A Westcountry Boy – Apostle of England. (London: Politicos Publishing, 2006). See also Michael Foot, Debts of Honour (London: Faber, 1980) and Sarah Foot, My Grandfather Isaac Foot (Bossiney Books. 1980).

6. We have focused on digitally searchable newspapers out of necessity during the pandemic.

7. Western Morning News, 5 Apri 1900.

8. Western Morning News, 13 December 1900

9. Western Morning News, 1 December 1900

10. Cornish & Devon Post, 9 February 1901

11. Warwick & Warwickshire Advertiser, 20 April 1901

12. Western Morning News, 13 June 1901

13. Western Morning News, 2 May 1901.

14. Western Morning News, 10 July 1901.

15. Western Morning News, 22 January 1902.

16. Cornish & Devon Post, 12 December 1903.

17. Cornish & Devon Post, 19 December 1903.

18. Western Morning News, 7 March 1903.

19. Western Evening Herald, 31 August 1903.

20. Western Morning News, 14 September 1903.

21. Western Morning News, 29 October 1903.

22. Western Morning News, 1 December1904.

23. Western Morning News, 1 November 1904.

24. Cornish & Devon Post, 1 October 1904

25. Totnes Weekly Times, 6 February 1909.

26. Totnes Weekly Times, 17 April 1909

27. Dartmouth & South Hams Chronicle, 31 December 1909.

28. Torquay Times & South Devon Advertiser, 28 January 1910

29. Dartmouth & South Hams Chronicle, 28 January 1910.

30. Western Morning News, 22 November 1910.

31. Western Times, 25 November 1910.

32. The Cornubian and Redruth Times, 27 January 1910

33. Leicester Daily Post, 14 December 1910.

34. Cornwall & Devon Post, 10 December 1910.

35. Leicester Daily Post, 14 December 1910.

36. The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 14 December 1910.

37. The Western Times, 14 December 1910

38. Cornish Echo and Falmouth & Penryn Times, Friday 6 January 1911

39. Royal Cornwall Gazette, Thursday 12 January 1911

40. Cornish & Devon Post, Saturday 11 February 1911

41. Western Morning News, Friday 7 April 1911

42. Cornish & Devon Post, Saturday 11 February 1911

43.Western Daily Mercury, Wednesday 28 February 1912

44. Cornish Guardian, Friday 10 July 1914

45. AJP Taylor, The Struggle For Mastery in Europe, 1848-1914 (1954).

46. Western Morning News, Tuesday 1 September 1914

47. Cornish Guardian, Friday 18 September 1914

48. Western Evening Herald, Tuesday 6 October 1914

49. Cornish Guardian, Friday 9 October 1914

50. Cornish Guardian, Friday 16 October 1914

51. Western Morning News, Friday 28 July 1916

52. Western Morning News, Wednesday 28 March 1917

53. West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, Thursday 20 April 1916

54. Western Morning News, Tuesday 19 December 1916

55. Western Morning News, Thursday 17 October 1918.

56. Western Times, Wednesday 13 November 1918.

57. Cornish Guardian, Friday 29 November 1918.

58. Western Morning News, Friday 13 December 1918.

59. Western Morning News – Monday 02 December 1918.

60. Cornish Guardian, Friday 20 December 1918.

61. Cornish Guardian, Friday 20 December 1918.

62. Evening Telegraph, 20 February 1922; see also The Times, 22 December 1936

63. The Times, 5 September 1921

64. Western Daily Press, 23 February 1922

65. The Observer, 30 March 1922

66. Gloucester Citizen, 24 February 1922

67. Western Daily Press, 23 February 1922

68. Gloucester Citizen, 23 January 1922

69. Cornishman, 22 February 1922

70. Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 27 February 1922

71. Western Morning News, 20 March 1922

72. Norikazu Kudo, ‘Tin Mining in Cornwall during the Inter-War Years 1918-38: A Chronology of Responses to the Changing Market Conditions’ in Keio Business Review, No. 50, 2015, pp. 25-53

73. Cornish Guardian, 10 February 1922

74. Western Times, 13 September 1864

75. Cornishman, 26 July 1906

76. Western Morning News, 20 March 1922

77. Cornish Guardian, 16 February 1923

78. The Observer, 26 February 1922

79. Derby Daily Telegraph, 18 January 1922

80. Gloucester Citizen, 20 February 1922

81. Aberdeen Journal, 22 February 1922. See also Dundee Courier, 27 February 1922

82. Ibid.

83. Hull Daily Mail, 27 February 1922

84. The Observer, 20 February 2022. Financial Times, 17 February 2022

85. Gloucester Journal, 4 March 1922

86. Nottingham Evening Post, 18 April 1922

87. Aberdeen Journal, 27 February 1922

88. Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 15 June 1922

Bob Keys is an Associate of the Institute of Cornish Studies, and Film & Folklore Director of Cornish Story. He lives in his native South-East Cornwall and was formerly Head of History at the University of St Mark & St Johns in Plymouth.

Chris Carter is a Professor of Strategy and Organisation at the Business School of the University of Edinburgh. He is a Cornishman and keenly interested in contemporary and historical issues relating to Cornwall.

Garry Tregidga is Co-Director of the Institute of Cornish Studies. His research interests include regional politics in Britain and he was awarded a PhD for his study of the Liberal Party in the South West after the First World War.

Some one from humble beginning can do so much by 21 then becoming a mp and solicitor a true gent