Helen Bartrop Hocking’s portrayal of her chosen village differs from the other articles in that it is presented in the form of an interview providing both personal and community information. There is also a huge bonus in that we will be publishing the audio recording of Christine Mary Bartrop.

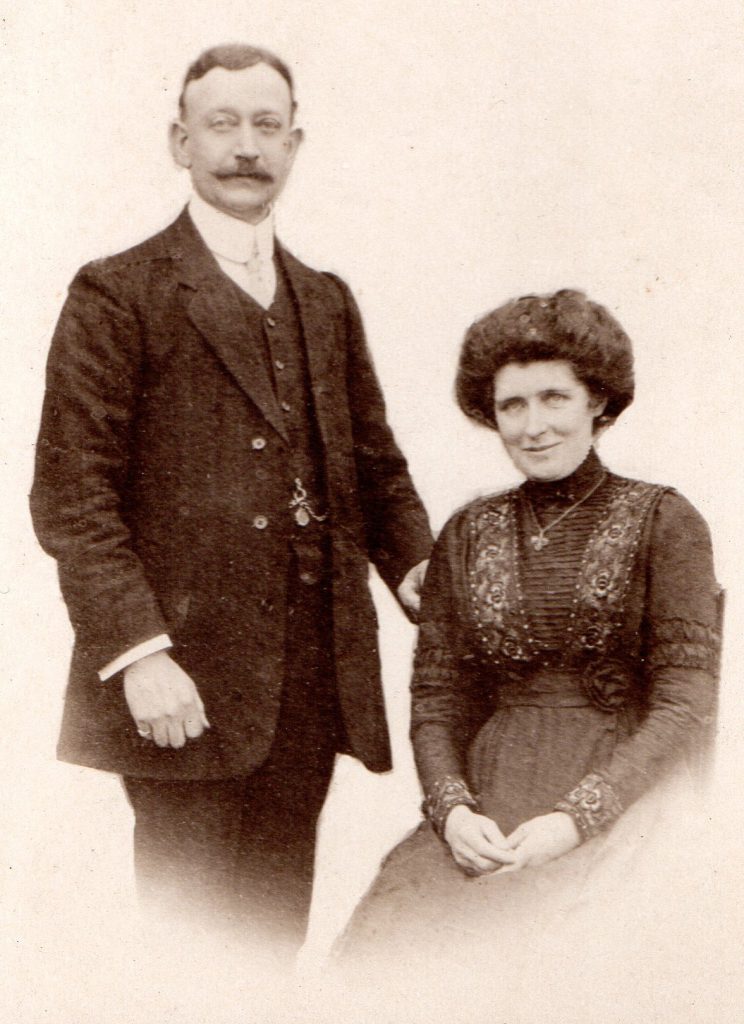

Our Gran was a Kilk maid, born and bred. I say “our” because she has three other grandchildren, besides me, alive in this world and five great-grandchildren. Her name was Christine Mary Bartrop (née Trewin) born 25thJune, 1918. A modest, hard-working, strong headed woman with a heart of gold, is how I will forever remember her. Like many Cornish people, she kept her own counsel and never had a bad word to say about anybody, even the few who wronged her in life. In her twilight years, I visited her at home frequently and in a time of her choosing, mind, I would listen to stories of her (almost) one hundred years of life experience. Everything from growing up in the village, surviving war, meeting our future grandfather, Reginald, who was posted to Cleave Camp and lodged at The London Inn during his RAF service, to starting a business in Bude with him that brought television to the area for the first time. After the tragedy of his death by drowning in 1961, she raised their children alone and continued to work in the shop until retiring aged 85. The whole town mourned him, alongside that of Mr Dempster, the local photographer who had also “gone out in the boat”, off the breakwater that day. Our Gran never married again. She wore her husband’s “wings” on her lapel at every fine occasion attended. She stood her ground against the wishes of the townsmen of the time and saw him buried in Kilk, within the grounds of St James the Great (brother to St John the Evangelist) like so many of her people laid to rest therein. And where, in Kalann Gwav1 rain, she was herself, finally reunited with him. Formidable at times, she had the mark of strength and self-discipline, so often found in true Cornish matriarchs, even those who were raised with no ideas about being “Cornish not English”, or of one day becoming recognised as part of a Protected National Minority. The interview that follows was recorded in the Spring of 2005, some eleven years before she passed on with the speed of a bird set free. Knowing her as I did, I can tell that she is trying hard to speak with the manners of the Church of England school where she was taught, yet every now and then aitches will be dropped and the local dialect still found in the village of Kilk can be heard. Moreover, I never knew her to use “Kilkhampton” as much as she does in conversation here with Freda E Hockin, founder of Launcells Local History Group, who also sounds so beautifully Cornish.

A full transcript of the oral interview follows below.

Freda: “Today is 10th March 2005 and I’m talking to Mrs Christine Bartrop, of Bude… Mrs Bartrop what date were you born?”

Christine: “June 25th 1918.”

Freda: “And you were born?”

Christine: “Trelawny, Kilkhampton.”

Freda: “Yes. And your parents were?”

Christine: “My Father was Francis Trewin and my Mother Mary Trewin she was Hawken before she was married.”

Freda: “And, um, what was her job, before she was married?”

Christine: “She was … she came from Bodmin and was a teacher at the Church of England school. And that was ‘ow she met my Father and they ‘ventually married.”

Freda: “And um, then they had a family and er, you had brothers and sisters?”

Christine: “Yes. I had 3 older brothers, Frank, Vivian and Eric. And a sister [Esther] but she died at 6 months old and then Barbara. She was, um, 6 years younger than me.”

Freda: “Yeah. Then you said, your Mother died when you were young?”

Christine: “Yes, my Mother unfortunately died when I was 6. My brothers were older. Frank was the eldest and he was 12, at the time. And, er, my Aunt (Ellen Trewin) at [what is now] the New Inn brought up my sister, Barbara. She was only 10 months old when Mother died… I see the thing’s working there…” (referring to the recording equipment with a chuckle!)

Freda: “Yes. Then, you had a lady come look after you, you said…”

Christine: “Yes, a Miss Annie Heard came as ‘ousekeeper and did the cooking and cleaning. She had a little cottage of her own up the village and she looked after us very well.”

Freda: “And then, where did you start school first?”

Christine: “Yes, I went to the Wesleyan Methodist School in West Street to start with and when I was about 8, we moved to the Church of England school, and, all but my brother Frank, and he stayed on, and went to the Council School that was built, I think, by Mrs Thynne, who was on the Education Committee down at Truro.”

Freda: “So, can you tell me something about the Trewins? uh, not Trewins… the Thynnes?”

Christine: “Yes, Mrs Thynne lost her husband in the first world war. There is a memorial erected to him that stands in the lower square.”

[Here the recording stops unexpectedly! Gran’s earlier observation foresaw this, I reckon]

Freda: “Right, we’ll set off again. Now, can you tell me some more about Mrs Thynne?”

Christine: “Oh, Yes. She lost her husband in the First World War and there’s a memorial to ‘im, in the Lower Square, Kilkhampton.”

Freda: “Yeah. And what kind of Lady was Mrs Thynne?”

Christine: “Well, we used to see her walking round Kilkhampton and she got a big dog with her. And she had a chauffeur and ‘e drove either a Daimler or a Rolls Royce, and she went to Truro on… Did I say that…?”

Freda: “Yeah, the Education Committee.”

Christine: “Yes. Education…”

Freda: “But she was also a magistrate, wasn’t she?”

Christine: “Yes, she was also a magistrate in … when there was a Court at Stratton. And um, if anybody from Kilkhampton came up in front of her, she used to make the fines a bit more, if they were fined for something… heh! heh! …because they came from Kilkhampton!”

Freda: “I hear she was quite a tarter!”

Christine: “Yes.” [laughter from them both]

Freda: “It was quite sad when she died and it didn’t remain in the Thynne family very long after that did it? The Estate…”

Christine: “No. Squire came for a little while and, um, then it was sold. And it’s now a place with the chalets and things like that, for ‘olidays.”

Freda: “And you said that they owned a tremendous amount of property in Kilkhampton?”

Christine: “Yes, the Thynne’s owned a lot of property in Kilkhampton. All the cottages were sold off. Some of the tenants bought their own cottages, and, I suppose, others that couldn’t afford it, moved out, you know.”

Freda: “They employed quite a lot of people as well, didn’t they? From the surrounding area.”

Christine: “Yes.”

Freda: “Yeah. Can you remember anybody who worked there, for Mrs Thynne?”

Christine: “Oh, Yes. She kept the gardeners, you know, for doing the gardens down there, they were very nice gardens… ‘eld some fetes, occasionally, down there.”

Freda: “So, moving on from Mrs Thynne, we’ll talk about your father again, now, what did he do?”

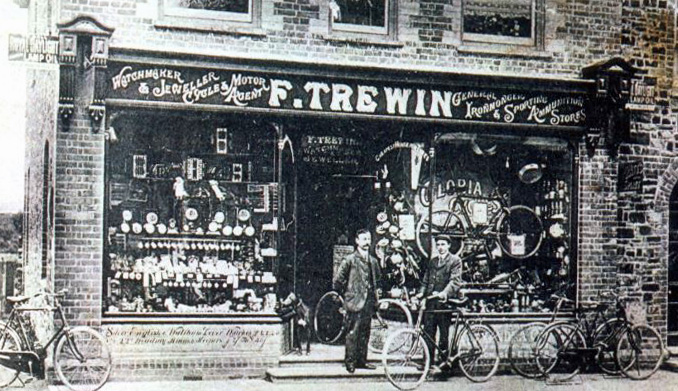

Christine: “He was a watchmaker and jeweller and sold ironmongery as well and eventually when the boys grew up and left school he started up a garage selling petrol and all that.”

Freda: “So, when you said – we’ll talk about the wartime – you said, your brothers had gone off to war.”

Christine: “Yes.”

Freda: “And so, what happened then, to the business?”

Christine: “I was only one left at ‘ome. My sister, Barbara, was training as a teacher and my husband taught me how to drive a car and I kept the rounds going. We worked up around in the country, and I kept that going, kept the shop open. I charged up accumulators and took people their accumulators because there was no electric about very much, then.”

Freda: “And also, you talked about the paraffin?”

Christine: “Yeah, I sold paraffin because that was the most, um, thing for cooking and lighting, back then.”

Freda: “So what kind of lamps would they have been using, then? The old oil lamps?”

Christine: “Yes. Oil lamps with wicks and I suppose, some had candles you know, still.”

Freda: “Yes. And then they graduated on to, I can remember a Tilly lamp and Tilly lanterns. Did you sell those?”

Christine: “Yes. I think me Father used to sell those, you know. With little mantels…”

Freda: “And then there was the old Primus…”

Christine: “Yes.”

Freda: “A lot of people used a Primus, didn’t they?”

Christine: “Yes. That took paraffin and methylated spirits. That was another thing we sold was, methylated spirits. You had to ‘ave methylated spirits to start it off, I think, didn’t ‘e?”

Freda: “Yes. I believe so, yes. So then, when your husband came back from the war, you got married?”

Christine: “We got married in 1943, during the War. And lived on there, in the back of the shop. And ‘ventually we moved to Bude.”

Freda: “So can you tell me something about your wedding outfit? How you were able to get…”

Christine: “Yes. The people in the country were very good. They didn’t need all the coupons that they had and they very kindly let me ‘ave a few coupons. That ‘elped with the wedding clothes and, we had the reception at the London Inn. About twenty-five people, very quiet sort of affair?”

Freda: “So who married you? The Vicar of Kilkhampton?”

Christine: “Yes, the Reverend Greener.”

Freda: “So, what did your outfit comprise? What did you wear…”

Christine: “Oh, ‘es. I wore a two-piece, pale blue frock, with maroon hat, maroon gloves and maroon shoes. Yes. So it was bought. Didn’t have hands made or anything. Think I went t’Exeter and bought those.”

Freda: “So how would you have got to Exeter then? Did you have enough petrol to get to

Exeter? Did you get to Exeter by car, or… bus up?”

Christine: “No. Caught the train.”

Freda: “Oh, the train, of course, yes, the train was still…down at Whitstone Station.. Or Bude, did you go to Bude?”

Christine: “Yes, we went from Bude. We used to be able to catch ‘Gist’, the carrier, you know, ‘e was very handy, he used to go to Bude twice a day and bring back stuff from the Station. Medicine from the Doctors for people. But ‘e was stopped from carrying for people by the bus company, because, I suppose, theym taking trade from the bus. Us used to ‘ave a bus come up from Bude and go through to Bideford but eventually that was closed down.”

Freda: “So, can you remember the shops that were in Kilkhampton at that time?”

Christine: “Yes, there was two grocery shops and drapers. You see they had grocery one side and drapery the other. They were both the same.”

Freda: “What were they called?”

Christine: “One was called Dayman’s and the other one was called Walkey’s. Eventually, Walkey’s gave up the grocery side and just had drapery and the Dayman’s closed down and you know, a big firm, like, International or somebody bought it, but since then it’s been owned by private people.”

Freda: “So, what about the Post Office?” [the Walkey’s were also Cousins to Gran, by marriage].

Christine: “Yes, that was run by a cousin of my Father’s, Josh Trewin and he’s Sister worked behind the counter in the Post Office and, course, eventually they died, and that had to be run by, people that came in, fresh people came in to run it, you see.”

Freda: “So, you talked about the London Inn and then there was the New Inn, so who ran those two pubs?”

Christine: “Yes, my Uncle [Alfred Trewin] ran the New Inn with he’s wife [Ellen was affectionately known by all as Nelly] and the London Inn belonged to the PRHA and they ‘ad managers up there.”

Freda: “When you say the PRHA… that’s the…”

Christine: “Yes a firm in London that used to run these places. I think it was something to do with the Church, I’m not sure.”

Freda: “So then when you married you lived in Kilkhampton for a short while and your children were born in Kilkhampton?”

Christine: “Yes. Susanne was born in 1946 and Stephen in 1950.”

Freda: “Yeah. And, can you remember – that was just after the war – how you managed, with rationing and baby milk and things like that?”

Christine: “Yes. I breast-fed both the children, I think Susanne went on to cow’s milk but Stephen had National Dried Milk. It was in a big blue tin. And then, there’s orange juice and cod liver oil, given out for children, to get their vitamins, I s’pose.”

Freda: “And can you talk about wartime bread?”

Christine: “Oh, ‘es. That was a mixture of brown bread and white, supposed to ‘ave been healthy but it didn’t taste too bad. And we had a Bakers shop up there.”

Freda: “So who ran the bakery, then?”

Christine: “Mr Staddon he was called. Came from away. I think Plymouth way. He and his wife ran it until they … well ‘e died, you know.”

Freda: “And then when you left Kilkhampton, you told me, you went to Bude to live…”

Christine: “‘es we ‘ad the little shop belonging to the Parson’s. Bakers. It was the top shop, the bottom was a restaurant and ‘ventually the restaurant closed and we took over the whole lot of it, you know.”

Freda: “You said, he worked in Stratton before that.”

Christine: “Yes he worked… or, he was a partner with Mr Fred Mortimer, who had a radio business. And electricals, you know.”

Freda: “So, where did your husband learn his trade, to be able to repair radios and things like that?”

Christine: “Well he learnt that in the Air Force, you see, course he was a radio mechanic in the Air Force, that was he’s job, so ‘e was familiar with radios and things, so ‘e’s able to repair things, you know…”

Freda: “Yeah. So he put his war time experiences to good use in ‘civvy’ street.”

Christine: “Yes, that’s right.”

Freda: “You told me earlier about, seeing a bomb crater…”

Christine: “Oh ‘es, it was one bomb fell out at Bradworthy. It just left a crater in the hedge out there. I used to pass it when I was on my rounds but fortunately nobody was killed or injured, or anything.”

Freda: “Now, can you tell me about Coronation Day?”

Christine: “Oh, yes, it was very busy up there, the village was decorated and my husband managed to put a television out in the garage, with seats for people to see. ‘Course it was only black and white…”

Freda: “This was in Kilkhampton?”

Christine: “‘es. And also, there was one up in Grenville Room. In Kilkhampton you could get a better picture, because we’re ‘igher up you know, than most places but, of course, it was only in black and white… not quite so good as the colour these days… heh! heh!”

Freda: “Right now, can you tell me about long families back at the time…”

Christine: “Oh, yes. Well, there was a Mrs Heard, she lived in the row of houses from the Policeman, what was called Ivy Cottage and she had 24 children. Mrs Shaddick is, I think, the last one, that’s living, isn’t it?”

Freda: “Yes, she’s done very well. She’s a hundred and three.”

Christine: “Yes, Raymond’s Mother. She’s the longest living of ‘em.”

Freda: “Yes, so, how big was the house? How many bedrooms did the house have?”

Christine: “Well back when the family were being born they lived in a cottage on the farm he worked on a farm, and used to ‘ave a decent sized house. ‘Course they weren’t all home together, because the eldest were out working, you know, so. One or two of ‘em died, I think, but ‘twasn’t so very long ago that there were sixteen of ‘em still living.”

Freda: “Yeah…”

Christine: “They’ve all had families. She had a lot of grandchildren and great grandchildren…. Heh!”

(And here the Recording ends)

“The country” was a term given to the vast Grenville acreage of old, that spanned the Cornish border. Recently placed signs, seen going in to the village, read: “Welcome to Kilkhampton – The Grenville Country” (much to the annoyance of those residents who would rather see St Piran representation). Mrs Anita Constance Thynne, the Lady of Penstowe, was wife to Lieut-Colonel Algernon Carteret Thynne, who was killed in the Great War, whilst fighting in Palestine. The Squire, Gran mentioned, was his brother, and consequent successor to the Estate, Captain George Augustus Carteret Thynne. The Manors of Morwenstow, Kilkhampton and Stratton were owned by the Thynne family, as well as land and property in Devon and other parts of England. “A Concise Dictionary of Cornish Place-Names”, written by Craig Weatherhill, states: Kilkhampton (Kelk c.839), Kelgh, Kylgh. “circle, ring”.

What a pleasure to read dad would have loved it as I have

Delightful read, which has Inspired me to find out more about King Brychan, King of the Christian kingdom of Brecknock in south Wales during the fifth century. Many of Brychan’s twenty-four children are said to have become Cornish saints. I am equally happy to confirm that neither the nature of Brychan’s story – nor the extent of the Heard family suggested in the account – reflect the actual Heard family line in any way whatsoever!

Delightful stories, which have inspired me to learn more about King Brychan, King of the kingdom of Brecknock in south Wales. Many of Brychan’s large family of 24 sons and daughters became Cornish saints. I am happy to confirm that any parallel to the nature and extent of the Heard family and their family line does not bear out in any way whatsoever – in fact!

Delightful stories, which have inspired me to learn more about King Brychan, King of the kingdom of Brecknock in south Wales. Many of Brychan’s large family of 24 sons and daughters became Cornish saints. I am happy to confirm that any parallel to the nature and extent of the Heard family and their family line does not bear out in fact!

Lovely to see my mother’s interviews being used this way. I shall show ‘re this next time I visit.

This is so lovely to listen to as my and my sister’s great grandfather was Francis Trewin.

Thank you very much.

I was so thrilled to come across this interview as I am very interested in local history and the families. We lived in Kilkhampton for six years, Bude for 11 years and now live in Grimscott (Launcells) since 2017. We are members of Launcells History Group and have the pleasure of knowing Freda Hockin. There are so many wonderful stories to be told still!